Sip Every Drop: Inaccessible and Jeopardized Water Resources in Nigeria and Ukraine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EU-UKRAINE PARLIAMENTARY ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE First Meeting 24-25 February 2015

EU-UKRAINE PARLIAMENTARY ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE First Meeting 24-25 February 2015 FINAL STATEMENT AND RECOMMENDATIONS Pursuant to Article 467 (3) of the Association Agreement Under the co-chairmanship of Mr. Andrej Plenković on behalf of the European Parliament and of Mr Ostap Semerak on behalf of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, the first meeting of the EU-Ukraine Parliamentary Association Committee (PAC) was held in Brussels on 24-25 February 2015. This first meeting was inaugurated by the President of the European Parliament, Mr Martin Schulz, and the Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, Mr Volodymyr Groysman. The Parliamentary Association Committee, having considered the state of play of EU-Ukraine relations and the overall security and political situation in Ukraine, agreed upon the following final statement and recommendations. The Parliamentary Association Committee (PAC): 1. Commemorates together with the Ukrainian people the first anniversary of the Revolution of Dignity; admires the courage and determination of the Ukrainian people who, a year ago, stood for and defended their right – even at the sacrifice of their own lives – to live in a democratic and European state, free to decide on its own future; On the overall political and security situation: 2. Strongly condemns the fact that Ukraine has been subject to Russia’s aggressive and expansionist policy and undeclared hybrid war, which constitutes a threat to the unity, integrity and independence of Ukraine and poses a potential threat to the security of the EU itself; emphasises that there is no justification for the use of military force in Europe in defence of so-called historical or security motives; 3. -

Ukraine Report FINAL 0712 COMPLETE-Compressed

THE OPPORTUNITIES FOR UKRAINE IN A LOW-CARBON FUTURE December 2017 The Bellona Foundation, Kiev, Ukraine, December 2017 Authors: Oskar Njaa; [email protected] Ana Serdoner; [email protected] Larisa Bronder; [email protected] Keith Whiriskey; [email protected] Disclaimer: Bellona endeavours to ensure that the information disclosed in this report is correct and free from copyrights but does not warrant or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, complete- ness, interpretation or usefulness of the information which may result from the use of this report. © 2017 by the Bellona Foundation. All rights reserved. This copy is for personal, non-commercial use only. Users may download, print or copy extracts of content from this publication for their own and non-commercial use. No part of this work may be reproduced without quoting the Bellona Foundation or the source used in this report. Commercial use of this publication requires prior consent of the Bellona Foundation. Acknowledgement: This report was supported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway and the Embassy of the Kingdom of Norway in Ukraine. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 5 1 Past & Current economic and industrial development of Ukraine ........................................... -

The European Union's Policy Towards Its Eastern Neighbours

Review of European and Russian Affairs 12 (2), 2018 ISSN 1718-4835 THE EUROPEAN UNION’S POLICY TOWARDS ITS EASTERN NEIGHBOURS: THE CRISIS IN UKRAINE1 Tatsiana Shaban University of Victoria Abstract The European Union’s neighbourhood is complex and still far from being stable. In Ukraine, significant progress has occurred in many areas of transition; however, much work remains to be done, especially in the field of regional development and governance, where many legacies of the Soviet model remain. At the crossroads between East and West, Ukraine presents an interesting case of policy development as an expression of European Union (EU) external governance. This paper asks the question: why was the relationship between the EU and Ukraine fairly unsuccessful at promoting stability in the region and in Ukraine? What was missing in the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) in Ukraine that rendered the EU unable to prevent a conflict on the ground? By identifying security, territorial, and institutional challenges and opportunities the EU has faced in Ukraine, this paper underlines the most important factors accounting for the performance of its external governance and crisis management in Ukraine. 1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the “Multiple Crises in the EU” CETD conference at University of Victoria, Feb 23rd, 2017. This conference was made possible by generous financial support from the Canada- Europe Transatlantic Dialogue at Carleton University. The author would like to acknowledge Amy Verdun, Zoey Verdun, Valerie D'Erman, Derek Fraser, and two anonymous reviewers of this journal for their comments on earlier drafts of this work. -

Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional Crisis

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2019 Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional Crisis Nicholas Pehlman The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3073 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional Crisis by Nicholas Pehlman A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © Copyright by Nick Pehlman, 2018 All rights reserved ii Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional Crisis by Nicholas Pehlman This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Mark Ungar Chair of Examining Committee Date Alyson Cole Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Julie George Jillian Schwedler THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2016

INSIDE: l Photo essay: Maidan memories two years after – page 5 l Yale hosts exhibit about Euro-Maidan – page 9 l Ukrainian heritage plus Devils hockey – page 10 THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal W non-profit associationEEKLY Vol. LXXXIV No. 9 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 2016 $2.00 UNICEF reports: Crimean Tatar Jamala to represent Ukraine at Eurovision War in Ukraine affects by Zenon Zawada KYIV – Once again, Ukraine will make over 500,000 children political waves at the annual Eurovision Song Contest. Yet this time around, a UNICEF Crimean Tatar will represent Ukraine, as GENEVA/NEW YORK/KYIV – The announced on February 21. conflict in Ukraine has deeply affected Accomplished pop singer Jamala will get the lives of 580,000 children living in a unique chance to raise Europe’s aware- ness to the plight of her people in perform- non-government controlled areas and ing “1944,” a song that ties the current per- close to the front line in eastern Ukraine, secution by the Russian occupation to the UNICEF said on February 19. Of these, genocide in which Soviet dictator Joseph 200,000 – or one in three – need psycho- Stalin deported most of the Crimean Tatar social support. population to Uzbekistan. “Two years of violence, shelling and The Verkhovna Rada declared the 1944 fear have left an indelible mark on thou- forced deportation of Crimean Tatars a sands of children in eastern Ukraine,” genocide on November 12, 2015, and desig- said Giovanna Barberis, UNICEF repre- nated May 18 as the Day of Remembrance sentative in Ukraine. -

Project Document Template

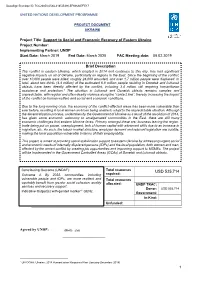

DocuSign Envelope ID: 7CC26850-058A-4185-B390-EF666A07FE17 UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME PROJECT DOCUMENT UKRAINE Project Title: Support to Social and Economic Recovery of Eastern Ukraine Project Number: Implementing Partner: UNDP Start Date: March 2019 End Date: March 2020 PAC Meeting date: 08.02.2019 Brief Description The conflict in eastern Ukraine, which erupted in 2014 and continues to this day, has had significant negative impacts on all of Ukraine, particularly on regions in the East. Since the beginning of the conflict, over 10,000 people were killed, roughly 24,000 wounded, and over 1.7 million people were displaced. In total, about two thirds (4.4 million) of the estimated 6.6 million people residing in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts have been directly affected by the conflict, including 3.4 million still requiring humanitarian assistance and protection.1 The situation in Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts remains complex and unpredictable, with regular and often deadly violence along the “contact line”, thereby increasing the impact of the conflict on human welfare and social and economic conditions. Due to the long-running crisis, the economy of the conflict-affected areas has been more vulnerable than ever before, resulting in local women and men being unable to adapt to the unpredictable situation. Although the decentralization process, undertaken by the Government of Ukraine as a result of the revolution of 2014, has given some economic autonomy to amalgamated communities in the East, there are still many economic challenges that eastern Ukraine faces. Primary amongst these are: business leaving the region, trade being put on pause, unemployment, lack of human capital with advanced skills due to an increase in migration, etc. -

Endc Occasional Papers 6/2017 Endc Occasional Papers

ENDC OCCASIONAL PAPERS 6/2017 ENDC OCCASIONAL PAPERS SERIES Volume I Vene-Gruusia 2008. aasta sõda – põhjused ja tagajärjed Ants Laaneots Volume II ENDC Proceedings Selected Papers Volume III Uurimusi Eesti merelisest riigikaitsest Toimetajad Andres Saumets ja Karl Salum Volume IV The Russian-Georgian War of 2008: Causes and Implications Ants Laaneots Volume V Eesti merejulgeolek. Uuringu raport Töögrupi juht Jaan Murumets Volume VI Russian Information Operations Against Ukrainian Armed Forces and Ukrainian Countermeasures (2014–2015) Edited by Vladimir Sazonov, Holger Mölder, Kristiina Müür and Andres Saumets ESTONIAN NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE RUSSIAN INFORMATION OPERATIONS AGAINST UKRAINIAN ARMED FORCES AND UKRAINIAN COUNTERMEASURES (2014–2015) SERIES EDITORS: ANDRES SAUMETS AND KARL SALUM EDITORS: VLADIMIR SAZONOV, HOLGER MÖLDER, KRISTIINA MÜÜR AND ANDRES SAUMETS AUTHORS: VLADIMIR SAZONOV, KRISTIINA MÜÜR, HOLGER MÖLDER, IGOR KOPÕTIN, ZDZISLAW SLIWA, ANDREI ŠLABOVITŠ AND RENÉ VÄRK ENDC OCCASIONAL PAPERS 6/2017 ENDC OCCASIONAL PAPERS Peatoimetaja / Editor-in-chief: Andres Saumets (Estonia) Toimetuskolleegium / Editorial Board: Sten Allik (Estonia) Nele Rand (Estonia) Wilfried Gerhard (Germany) Claus Freiherr von Rosen (Germany) Ken Kalling (Estonia) Karl Salum (Estonia) Jörg Keller (Germany) Vladimir Sazonov (Estonia) Enno Mõts (Estonia) Volker Stümke (Germany) Erik Männik (Estonia) René Värk (Estonia) Andreas Pawlas (Germany) Keeletoimetajad / Language Editors: Collin W. Hakkinen (USA) Reet Hendrikson (Estonia) Marika Kullamaa (Estonia) Epp Leete (Estonia) Amy Christine Tserenkova (USA) Nõuandev kogu / International Advisory Committee: Martin Herem (Committee Manager, Estonia) Rain Liivoja (Australia) Hubert Annen (Switzerland) Gale A. Mattox (USA) Richard H. Clevenger (USA) Ago Pajur (Estonia) Angelika Dörfl er-Dierken (Germany) Robert Rollinger (Austria) Sharon M. Freeman-Clevenger (USA) Michael N. Schmitt (USA) Thomas R. -

Rapid Review on Inclusion and Gender Equality in Central and Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia © United Nations Children’S Fund (UNICEF) July 2016

Rapid Review on Inclusion and Gender Equality in Central and Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) July 2016 Permission is required to reproduce any part of this publication. Permission will be freely granted to educational or non-profit organizations. To request permission and for any other information on the publication, please contact: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) The Regional Office for Central and Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CEE/CIS) Palais des Nations CH-1211 Geneva 10 Switzerland Tel: +41 22 909 5111 Fax: +41 22 909 5909 Email: [email protected] All reasonable precautions have been taken by UNICEF to verify the information contained in this publication. Suggested citation: United Nations Children’s Fund, Rapid Review on Inclusion and Gender Equality in Central and Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia, UNICEF, Geneva, July 2016. Cover photo: © UNICEF/UNI114967/Holt 2 I UNICEF 1 Executive Summary .....................................................................................................4 Contents 2 Methodology .................................................................................................................7 3 Children with disabilities .............................................................................................8 3.1 Current situation .......................................................................................................8 3.2 Main child rights violations .................................................................................... -

Military Conflict in Eastern Ukraine — Civilization Challenges to Humanity

Environment – People – Law Military Conf lict in Eastern Ukraine – Civilization Challenges to Humanity Environment – People – Law Military Conflict in Eastern Ukraine — Civilization Challenges to Humanity Lviv • 2015 Universal Decimal Classifi cation 504.9 Bibliographic classifi cation 20.1(4Укр) В 63 AUTHORS: Ol’ha Melen’-Zabramna, Sofi a Shutiak — р. 1 (Ol’ha Melen’-Zabramna — subchapter 1.1, Sofi a Shutiak — subchapter 1.2); Alla Voytsikhovska, Kateryna Norenko, Oleksiy Vasyliuk — р. 2 (Alla Voytsikhovska — subchapters 2.1, 2.2, 2.4, 2.7, Kateryna Norenko — subchapter 2.3, Oleksiy Vasyliuk — subchapters 2.5, 2.6); Kateryna Norenko, Alla Voytsikhovska, Oleksiy Vasyliuk, Oksana Nahorna — р. 3 (Kateryna Norenko — subchapters 3.1, 3.3.1, 3.3.2, Alla Voytsikhovska — subchapter 3.2, Oleksiy Vasyliuk — subchapter 3.4, Oksana Nahorna — subchapter. 3.5); Kateryna Norenko, Alla Voytsikhovska — р. 4 (Kateryna Norenko — subchapter 4.1, Alla Voytsikhovska — subchapter 4.2). Recommendations by Alla Voytsikhovska, Olena Kravchenko Edited by Olena Kravchenko Design: Olena Zhinchyna В 63 Воєнні дії на сході України — цивілізаційні виклики людству. / Львів: ЕПЛ, 2015. — 124 с. Th e manual off ers studies by International Charitable Environmental Law Organization «Environment-People-Law» (EPL) on the impact of military operations on the environment in eastern Ukraine, evaluation of damage caused to the environment, provides key environmental features in Donetsk and Luhansk regions before the confl ict, investigates factors about pollution and destruction of environmenal objects caused by military actions, including air, soil and water pollution, forest fi res, destruction of protected sites, provides the analysis of international studies of damage caused to the environment as a result of military confl ict conducted by international organizations in post-confl ict countries, lists key aspects of national and international environmental law during hostilities. -

Why Russia's Intervention in Ukraine Exposes the Weakness of International Law

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Journal of International Law 2015 The Return of Novorossiya: Why Russia’s Intervention in Ukraine Exposes the Weakness of International Law Adam Twardowski Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mjil Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Twardowski, Adam, "The Return of Novorossiya: Why Russia’s Intervention in Ukraine Exposes the Weakness of International Law" (2015). Minnesota Journal of International Law. 351. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mjil/351 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Journal of International Law collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Return of Novorossiya: Why Russia's Intervention in Ukraine Exposes the Weakness of International Law Adam Twardowski* I. INTRODUCTION The end of the Cold War unleashed optimism that a new relationship between the West and Russia could be grounded in mutual adherence to international norms and institutions.' Although Russia's emergence from its Soviet mold was hobbled by economic turmoil and political corruption,2 its attempt to instigate democratic and legal reforms 3 and later enter the WTO 4 suggested that the geopolitical divide between the West and Russia had been supplanted by Russia's desire to integrate itself into the global economy. However, the events of 2014 and 2015 in Ukraine have dashed the West's hopes about Russia's * I would like to thank my mother, Malgorzata Twardowska, for her love and sacrifices throughout the years, and my grandparents, Halina and Zbylut Twardowski, for their unwavering support. -

The Ukrainian Challenge for Russia: Working Paper 24/2015 / [A.V

S SUMMER SCHOOLS EXPERT COMMENTARIES S GUEST LECTURES CENARIOS T S S TABLE NTERNATIONAL RELATIONS C I S NALYSIS AND FORECASTING FOREIGN POLICY ISCUSSIONS A T D C REFERENCE BOOKS DIALOGUE ETWORK SCIENCE WORKING PAPERS DUCATION N PROJE OUND E REPORTS NALYSIS AND FORECASTING URITY R A S ATION C C PROJE E ORGANIZATION OMPETITIONS C NTERNATIONAL ACTIVITY CONFERENCES DU E I S S S FOREIGN POLICY TALENT POOL CS S EDUCATION POOL POLITI EPORTS OUND TABLES ION R R ENARIO GLOBAL POLITICS ETWORK C NTERNATIONAL I N IVIL OCIETY INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS S C S LOBAL RELATION G TALENT SS EFERENCE BOOKS NTERNATIONAL Y R I Y RUSSIAN Y S C S ORGANIZATIONS DUCATION C E E INTERNATIONAL U SECURITY C RELATION SUMMER C AFFAIRS COUNCIL POLI SCHOOLS IALOGUE IETY D TING ONAL OUND I R GUEST LECTURES C SC O S TABLES I TY IGRATION EPORTS I R S A V ARTNERSHIP OREIGN P I NTERNATIONAL IBRARY OADMAPS XPERT R F E I S ONFEREN IPLOMA D M C L URITY GLOBAL NTERNAT MIGRATION COMMENTARIES IVIL C I ACT S ILATERAL NTHOLOGIE C POOL D SCIENCE C REPORTS I BOOK E ISCUSSIONS INTERNSHIPS B A D IPLOMA E WEBSITE PARTNERSHIP INTERNSHIPS S S Y C TALENT C DIALOGUE GLOBAL NTHOLOGIESGLOBAL Y A C S D POLI FORE SCIENCE CONFERENCES POLI Y S C ITE EFEREN S S NALYSISSCIENCE IGRATION A IBRARY OADMAP EB ENARIO OREIGN R IPLOMA C F R L M OREIGN D S W NALY AND FORECASTING F S DIALOGUE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS A AND S NETWORK INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS E CLUB MEETINGS DIALOGUE DIPLOMACY PROJECTS HOOL S S C IALOGUE S T D C URITY UMMER ITE E S HIP C S OMMENTARIE TURE IVIL OCIETY C S C S EBSITE E C W C -

Corruption in Ukraine

Corruption in Ukraine Corruption in Ukraine: Rulers’ Mentality and the Destiny of the Nation, Geophilosophy of Ukraine By Oleg Bazaluk Translated by Tamara Blazhevych Proofread by Lloyd Barton Corruption in Ukraine: Rulers’ Mentality and the Destiny of the Nation, Geophilosophy of Ukraine By Oleg Bazaluk This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Oleg Bazaluk All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-9689-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-9689-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................... vii Introduction ................................................................................................ ix Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 The Geophilosophy of Ukraine: Ukraine and the Ukrainians in 1990 Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 45 14 Years of Authoritarianism (between 1990 and 2004): How the Ukrainians Learnt to Give and Take Bribes Chapter Three .........................................................................................