Dietmar Winkler Growing Consensus the Dialogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz

INSTITUTE OF ECUMENICAL THEOLOGY, EASTERN ORTHODOXY, AND PATRISTICS Head of Institute: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Dr. Pablo Argárate 8010 Graz, Heinrichstrasse 78, AUSTRIA Phone: +43-316/380-3181 E-mail: [email protected] CURRICULUM VITAE Education – Bachelor in Sacred Theology. Universidad Católica Argentina, Buenos Aires 1990 STB Thesis: “Maximos Confessor’s Μυσταγωγία in the Context of Early Commentaries on Liturgy” – Licenciate in Philosophy. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina 1986 Lic. Thesis: “From Gabriel Biel to Sören Kierkegaard through Martin Luther: Faith and Reason” – Dr. phil. Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina 1996 Dissertation: “ Ἀεικίνητος Στάσις. The dynamic of being towards unity in the reflection of Maximus the Confessor” Advisor: Prof. María Mercedes Bergadá – Dr. theol. Universität Tübingen, Germany, 2003 Dissertation: “Der Heilige Geist bei Symeon dem Neuen Theologen” Advisor: Prof. Dr. Hermann-Josef Vogt – Dr. phil. cand. Cultures and Languages of the Christian East. Fakultät für Kulturwissenschaften. Universität Tübingen (1997-2001) Dissertation: “The Syriac Liber Graduum and Messalianism” Advisor: Prof. Dr. Stephan Gerö Teaching Experience 2011– Full Professor and Director of the “Institute of Ecumenical Theology, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Pa- tristics”. Faculty of Theology, University of Graz 2019- “Master of Arts in Syriac Theology”, University of Salzburg: “The Great Theologians of the Golden Time (5th-9th c.): Christology and Ecclesiology”. 2009–13 Cross-appointed to the Department and Centre for the Study of Religion. University of Toronto 2007–11 Director of the Eastern Christian Studies Program 2006 Tenure 2003–11 Professor of Patristics & Historical Theology. Faculty of Theology. St. Michael’s College. Univer- sity of Toronto, Canada 2002–03 Assistant Professor of Liturgy. -

1 Common Formula on Christology Mixed Commission of the Dialogue

Common formula on Christology Mixed Commission of the Dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Coptic Orthodox Church "The Mystery of Redemption and Its Consequences for the Last Ends of the Human Person" FULL TEXT Report In the love of God the Father, by the grace of the Only Begotten Son, and by the gift of the Holy Spirit. On Friday, the 12th of February 1988, the mixed commission of the dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Coptic Orthodox Church met in the Monastery of Saint Bishoy, Wadi El Natrun, in Egypt. His Holiness Pope Shenouda III opened the meeting by prayer. His Excellency Giovanni Moretti, the Apostolic Pro Nuncio in Egypt, and Reverend Father Pierre Duprey, Secretary of the Vatican Secretariate for Promoting Christian Unity, attended this meeting representing His Holiness Pope John Paul II and enabled to sign this agreement. Also bishops delegated by His Beatitude Stephanos II Ghattas, Patriarch of the Coptic Catholic Church, were present and delegated to sign this agreement. We have rejoiced at the historical meeting that happened in the Vatican on May 1973, between His Holiness Pope Paul VI and His Holiness Pope Shenouda III. This was the first meeting since about 15 centuries between our two Churches. In that meeting we found ourselves in agreement on many issues of faith. In that meeting also a mixed commission was formed to discuss the issues of difference of doctrine and faith between the two Churches aiming at church unity. Previously in Vienna, September 1971, Pro Oriente arranged a meeting between theologians of the Catholic Church and those of the Oriental Orthodox Churches: the Coptic, the Syrian, the Armenian, the Ethiopian, and the Indian. -

The Holy See

The Holy See ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS JOHN PAUL II TO MEMBERS OF THE "PRO ORIENTE" FOUNDATION 29 March 1979 Lord Cardinal, Your Excellency, Ladies and Gentlemen, It is one of the unfathomable divine dispositions that you are only now able to pay to his successor the visit which, as delegation of the Board of Directors of the ecumenical Foundation "Pro- Oriente", together with your venerated founder and president, you already wished to pay to Pope John Paul I last year. I, therefore—representing at the same time also my unforgettable predecessor—receive you with all the greater joy and bid you a very hearty welcome, For fifteen years, "Pro Oriente"—completely in accordance with the name of the Foundation has—been concerned with dialogue with the Orthodox Churches, and in the last few years particularly with dialogue with the Old Eastern Churches. As I emphasized just recently in my first Encyclical, true ecumenical work means "openness, drawing closer, availability for dialogue, and a shared investigation of the truth in the full evangelical and Christian sense" (Redemptor Hominis, 6). Your many meetings, conversations, study sessions and publications have served this aim in a fruitful way. Through them, on the plane of personal contacts and specialized scientific research, you have contributed to better reciprocal acquaintance, to a deeper understanding of the different historical developments and traditions of the individual Churches of the East and of the West, and to a more conscious recognition of the rich common heritage which already exists. Looking back today, you can already point with joy and satisfaction to precious concrete results. -

Born April 15, 1963 in Wolfsberg/Carinthia (Austria). 1969

DIETMAR WERNER WINKLER Paris-Lodron University of Salzburg Center for the study of the Christian East Department Biblical Studies and Ecclesiastical History Universitätsplatz 1; A-5020 Salzburg, Austria-Europe Born April 15, 1963 in Wolfsberg/Carinthia (Austria). 1969 – 1973: Primary school. 1973 – 1981: Benedictine High School Academy of St. Paul's Abbey/Carinthia (Austria). RESEARCH FIELDS Past and present, theology, political contexts and culture of Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, Ethiopian and Indian Christianity; History and cultural exchange of Christianity along the Silk Roads (Persia, Central Asia, China); current ecumenical theological dialogues with Oriental Christianity; ACADEMIC BACKGROUND AND DEGREES December 2000 Habilitation (Dr. habil.) (University of Graz) for Patrology, History of Dogma and Ecumenical Theology. September 1998: Certificate in Syriac (Mahatma Ghandi University Kottayam/India). June 1995: Doctor Theologiae (Dr. theol., summa cum laude, University of Innsbruck). January 1991: Magister Theologiae (Mag. theol., summa cum laude, University of Graz). 1989 – 1990: Certificate in Ecumenical Studies (University of Geneva, Switzerland), Graduate School of Ecumenical Studies at the Ecumenical Institute of the World Council of Churches in Bossey. June 1989: Magister Philosophiae (Mag. phil., University of Graz/Austria). 1982-1989: Studies in Theology, Philology, Ancient History and Religious Pedagogics in Graz (Austria), Geneva (Switzerland) and Innsbruck (Austria) ACADEMIC POSITIONS Head of Department of Biblical Studies -

PRO ORIENTE Summer Course 2018 Information

PRO ORIENTE Wien | Salzburg | Graz | Linz Hofburg, Marschallstiege II 1010 Wien, Österreich +43 1 5338021 1 [email protected] www. pro-oriente.at Summer Course 2018 The World Council of Churches (WCC) Commemorating 70 Years of Ecumenism Vienna, July 9-12, 2018 After the Second World War, the World Council of Churches (WCC) was founded in 1948 as part of a grand peace project after the wartime atrocities. Leading persons from the ecumenical moment such as Willem Visser’t Hooft and John R. Mott intended a fellowship of churches which confesses the Lord Jesus Christ as God and Saviour according to the Scriptures. Today the churches in the WCC pursue the vision of ecumenism as they seek visible unity in one faith and one Eucharistic fellowship. The WCC promotes common witness in work for mission and evangelism, and engages in Christian service by meeting human need, breaking down barriers between people, seeking justice and peace, and upholding the integrity of creation. In the beginning most of the member churches were from Europe, including the Ecumenical Patriarchate and some Eastern churches. During the 1960s, the influx of the Orthodox Churches from then communist Eastern Europe and the churches from southern Africa brought new perspectives. It is a challenge that the Catholic Church is not a member of the WCC. However, it is a full member of the Faith & Order Commission and has representatives participating in many working groups and national ecumenical institutions. The PRO ORIENTE Summer Course focuses on: − The history of and changes in the ecumenical movement − The Joint Working Group between the Catholic Church and the WCC − New churches – new members − Local and national ecumenical work − The document ‘The Church: Towards a Common Vision’, published by the Faith & Order Commission in 2013 DVR-Nr.: 0029874(004) Speakers: − Rev. -

V.C. Samuel: the Person and His Work

V.C. Samuel: The Person and His Work By Fr. Dr. Ninan K. George CONTENT INTRODUCTION Birth and Childhood Education Higher Studies in Theology Parish Ministry Translation of Prayers Teaching Ministry Manjanikkara Malpan V.C. Samuel and His Family A Pioneering Pillar of Orthodoxy A Prophet of Truth A Pioneer Leader of Ecumenism V.C. Samuel and World Council of Churches V.C. Samuel and Unofficial Consultations between the Theologians of The Oriental and Eastern Orthodox Churches V.C. Samuel and Pro-Oriente V.C. Samuel in Indian Theological World CONCLUSION INTRODUCTION Writing on the historical and towering personalities who have rendered great, miraculous services for the welfare of society definitely needs ceaseless help from God; because one can succeed in his endeavors only because of God and His timely guidance. V. C. Samuel who lived in the 20th century was, truly speaking a man of intense vision on the content and future of his own religious community within which he was born and brought up. According to him, God is the cause of the tangible and intangible world. He strongly believed that everybody has the freedom to know God, provided God is also an object of study like all other studies, not based on reason and analysis but fully standing on faith in God. When anybody writes on V. C. Samuel this facet cannot be ignored. Throughout his life, he experienced God and God-events by becoming an ardent student of Theology, Christology, Ecclesiology and Church History. He never forgot to practice what he learned from his study materials. -

Projektarbeit Im Rahmen Des Universitätslehrganges Library and Information Studies Grundlehrgang 2017/2018 an Der Universität Wien

Projektarbeit im Rahmen des Universitätslehrganges Library and Information Studies Grundlehrgang 2017/2018 an der Universität Wien Bibliographische Datensätze der Bestände der Oberin-Gleixner-Bibliothek: Bestände zur Thematik Ökumene Bestände mit Widmungen, Notizen und Beilagen Eingereicht von: Daniela Böhm BA, Mag. Ursula Havlicek Betreut von: Mag. Dr. Alfred Friedl Fachbereichsbibliothek Theologie der Universitätsbibliothek Wien Datum: Wien, im August 2018 Erläuterungen zum Dokument Das vorliegende Dokument ist ein Ergebnis des im Rahmen des Universitätslehrganges Library and Information Studies durchgeführten Projektes zur „Oberin-Gleixner-Bibliothek“. Geschichte der Oberin-Gleixner-Bibliothek Christine Gleixner, 1926 in Wien geboren, kehrt nach ihrer Ordensausbildung und langjähriger Tätigkeit im Bereich der Ökumene in Holland, 1962 nach Wien zurück und übernimmt hier die Leitung des Ordens „Frauen von Bethanien“. Die kleine Gemeinschaft lebt und arbeitet in einer geräumigen Altbauwohnung in der Wipplingerstraße im ersten Wiener Gemeindebezirk. Die Arbeits- und Studienbibliothek, die auch StudentInnen und Interessierten zur Verfügung steht, wird bis 1996 von der Mitschwester Helene Czejka betreut, die einen Zettelkatalog (Nominal- und Schlagwortkatalog) führt. Nach dem Tod von Oberin Christine Gleixner (2015) wird die Niederlassung des Ordens in Wien und somit auch die Bibliothek aufgelöst. Die Bibliotheksbestände (ca. 110 Laufmeter) wurden 2016 von ihrer Kollegin Dr. Sigrid Mühlberger der Fachbereichsbibliothek Theologie der Universität Wien zur Verfügung gestellt. Das Projekt Ein Ziel des Projektes war, die „Oberin-Gleixner-Bibliothek“ soweit zu sichten und zu erschließen, dass eine nachfolgende Entscheidung über die Aufnahme von Titeln in den Bestand der Fachbereichsbibliothek Theologie ermöglicht wird. Von besonderem Interesse für die Fachbereichsbibliothek waren inhaltlich der Thematik Ökumene zuzuordnende Titel, sowie Bände, die persönliche Vermerke von Christine Gleixner oder anderen Personen enthalten (Widmungen, Notizen, Beilagen). -

A Short Biography of Rev. Dr. V.C. Samuel

A Short Biography of Rev. Dr. V.C. Samuel By Sunny Kulathakkal CONTENT Family and Religious Background Education Teaching Work Association with the Ecumenical Movement Publications Some Personal Data Family and Religious Background Rev. Dr. V. C. Samuel was born into a middle-class St. Thomas Syrian Christian family, Edayil at, Omalloor, Pathanamthitta in Central Travancore, which now forms part of the State of Kerala, India. He was born on 6th April 1912 as the fifth of six sons and three daughters of Late E.I. Cherian and late Annamma Cherian, both of them were persons of sterling character and deep Christian dedication. Samuel did, not start his life at a high level. During the early years of his life, he was sickly, but gradually he regained his health. His growth to religious scholarship and prominence was due to his inner compulsions and efforts on one hand and the atmosphere of religious devotion and Christian commitment in the family and the motivation of his parents. Late E. l. Cherian was by profession a school teacher and a recognized leader in the community. Conversant as he was with both the Sanskrit and Tamil languages, besides Malayalam, he had a collection of books in those languages which he used to read regularly as much as his Bible and other Christian writings. While he was a young man, Cherian came to appreciate the interest which the government of Travancore was expressing for the spread of education in the country. That was a time - towards the end of 19th and the early part of the 20th century – when children in around his native village had very little facilities for schooling. -

The Syriac Orthodox and Coptic Orthodox Churches in Austria: Inter-Church Relations and State Recognition

The Syriac Orthodox and Coptic Orthodox Churches in Austria: Inter-Church Relations and State Recognition Andreas Schmoller Mashriq & Mahjar: Journal of Middle East and North African Migration Studies, Volume 8, Number 1, 2020, pp. 76-102 (Article) Published by Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/785284 [ Access provided at 24 Sep 2021 13:46 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] Mashriq & Mahjar 8, no. 1 (2021) ISSN 2169-4435 Andreas Schmoller1 THE SYRIAC ORTHODOX AND COPTIC ORTHODOX CHURCHES IN AUSTRIA: INTER-CHURCH RELATIONS AND STATE RECOGNITION Abstract This article explores the inter-church and church-state relations of the Syriac Orthodox and Coptic Orthodox Churches in Austria. The strong historic role of the Catholic Church in Austria's political landscape provides the central framework to understand the “story of success” regarding relations with both the Catholic Church and state authorities in Austria. Summarizing the history of migration and establishment of diaspora churches in Austria, the article explores the impact of the support of the Catholic Church in the process of institutionalization. In addition, state recognition and examples of church- state interaction are highlighted. The findings support the conclusion that minority churches from the Oriental Orthodox tradition have benefitted strongly from their relations with the majority church and the state. However, their authority in both religious and political contexts also affects personal leadership and internal affiliations which can lead to divisions within the church communities. INTRODUCTION Patriarch Mor Ignatius Aphrem II Mor Karim on his first visit to Austria from 4–8 December 2014 declared: “Austria has embraced us.”2 This potentially included both church and state actors. -

Severus of Antioch and His Search for the Unity of the Church

Invitation for the Opening Session and the Conference: Severus of Antioch and his Search for the Unity of the Church: 1500 Years Commemoration of his Exile in 518 AD Opening Session February 7th 2018, 3 pm Bibliotheksaula, Hofstallgasse 2-4 Conference February 8th– 9th, 2018 Theological Faculty Salzburg, HS 101 (Icon: Abdo Badwi, OLM) Patriarch Severus of Antioch (512-38) is one of the most prominent theologians of the Syriac Golden Age, who worked tirelessly for the reunion of the imperial Church after the Council of Chalcedon (451). After six years as Patriarch in Antioch he fled from Emperor Justin I (518-27) to Egypt. With the 1500th anniversary of Severus’ expulsion into exile in 518, the aim of the conference is to draw attention to the significant role Severus played in Syriac Christianity, to study his theological and historical texts, to point out some of the aspects of his indefatigable work for the reunification of the Church and to reflect on the impact of his expulsion from Antioch on the history of Syriac Christianity. His Holiness Mor Ignatius Aphrem II, Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch, will give the inaugural address. Suryoye Theological FB Bibelwissenschaft Seminary und Kirchengeschcihte Salzburg Sektion Salzburg Opening Session: Wednesday 7th February, 15:00 (Bibliotheksaula) Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805) Minuet from The String Quintet in E major, Op. 13, No. 5 Welcome Aho Shemunkasho |Professor Syriac Theology Greeting Addresses Alois Halbmayr | Dean of the Theological Faculty Dietmar W. Winkler | President of Pro -

The 'Nestorian' Church: a Lamentable Misnomer

THE 'NESTORIAN' CHURCH: A LAMENTABLE MISNOMER S.P. BROCK THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD According to a very widespread understanding of church history the christological controversies of the fifth century were brought to a happy conclusion with the Definition of Faith issued at the Council of Chalcedon in 451. This definition was accepted as normative by both Greek East and Latin West (and hence, subsequently, by the various Reformed churches of the West). Only a few obstinate Orientals (so this conventional picture would have it) refused to accept the Council's Definition of Faith, whether it be out of ignorance, stupidity, stubbornness, or even separatist nationalist aspirations: these people were, on the one side of the theological spectrum, the Nestorians, and at the other end, the Monophysites - heretics both, the former rejecting the Council of Ephesus (431) and believing in two persons in the incarnate Christ, the latter rejecting the Council of Chalcedon and holding that Christ's human nature was swallowed up by the divine nature. It need hardly be said that such a picture is an utterly pernicious caricature, whose roots lie in a hostile historiographical tradition which has dominated virtually all textbooks'of church history from antiquity down to the present day, with the result that the term 'Nestorian Church' has become the standard designation for the ancient oriental church which in the past called itself 'The Church of the East', but which today prefers a fuller title 'The Assyrian Church of the East'. Such a designation is not only discourteous to the modern members of this venerable church, but also - as this paper aims to show - both inappropriate and misleading. -

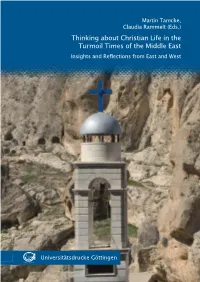

Thinking About Christian Life in the Turmoil Times of the Middle East

„Studies in the Middle East“ is a one-year programme at the Near East School of Theology in Beirut (NEST). In honour of its 20th anniversary, academics and Martin Tamcke, teachers from the NEST and from Germany met at Georg-August University Claudia Rammelt (Eds.) in Göttingen and in the nearby Coptic Orthodox Monastery in Höxter-Brenk- hausen to discuss the current situation in the Middle East and possible ways to initiate a spiritual new beginning in this crisis and war-ridden region. The Thinking about Christian Life in the present volume offers various contributions that were made on the subject. Turmoil Times of the Middle East Insights and Reflections from East and West Thinking about Christian Life in the Turmoil Times of Middle East Thinking Tamcke/Rammelt (Eds.) ISBN: 978-3-86395-443-7 Universitätsdrucke Göttingen Universitätsdrucke Göttingen Martin Tamcke, Claudia Rammelt (Eds.) Thinking about Christian Life in the Turmoil Times of the Middle East Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung - Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 International Lizenz. erschienen in der Reihe der Universitätsdrucke im Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2020 Martin Tamcke Claudia Rammelt (Eds.) Thinking about Christian Life in the Turmoil Times of the Middle East Insights and Reflections from East and West 6th International Consultation of “Study in the Middle East” (SiMO) and Near East School of Theology (NEST) Göttingen, April 24 – 27, 2019 Selected contributions Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2020 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.dnb.de> abrufbar.