SAVING FACE the ART and HISTORY of the GOALIE MASK Revised Edition Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1977-78 Topps Hockey Card Set Checklist

1977-78 TOPPS HOCKEY CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Marcel Dionne Goals Leaders 2 Tim Young Assists Leaders 3 Steve Shutt Scoring Leaders 4 Bob Gassoff Penalty Minute Leaders 5 Tom Williams Power Play Goals Leaders 6 Glenn "Chico" Resch Goals Against Average Leaders 7 Peter McNab Game-Winning Goal Leaders 8 Dunc Wilson Shutout Leaders 9 Brian Spencer 10 Denis Potvin Second Team All-Star 11 Nick Fotiu 12 Bob Murray 13 Pete LoPresti 14 J.-Bob Kelly 15 Rick MacLeish 16 Terry Harper 17 Willi Plett RC 18 Peter McNab 19 Wayne Thomas 20 Pierre Bouchard 21 Dennis Maruk 22 Mike Murphy 23 Cesare Maniago 24 Paul Gardner RC 25 Rod Gilbert 26 Orest Kindrachuk 27 Bill Hajt 28 John Davidson 29 Jean-Paul Parise 30 Larry Robinson First Team All-Star 31 Yvon Labre 32 Walt McKechnie 33 Rick Kehoe 34 Randy Holt RC 35 Garry Unger 36 Lou Nanne 37 Dan Bouchard 38 Darryl Sittler 39 Bob Murdoch 40 Jean Ratelle 41 Dave Maloney 42 Danny Gare Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Jim Watson 44 Tom Williams 45 Serge Savard 46 Derek Sanderson 47 John Marks 48 Al Cameron RC 49 Dean Talafous 50 Glenn "Chico" Resch 51 Ron Schock 52 Gary Croteau 53 Gerry Meehan 54 Ed Staniowski 55 Phil Esposito 56 Dennis Ververgaert 57 Rick Wilson 58 Jim Lorentz 59 Bobby Schmautz 60 Guy Lapointe Second Team All-Star 61 Ivan Boldirev 62 Bob Nystrom 63 Rick Hampton 64 Jack Valiquette 65 Bernie Parent 66 Dave Burrows 67 Robert "Butch" Goring 68 Checklist 69 Murray Wilson 70 Ed Giacomin 71 Atlanta Flames Team Card 72 Boston Bruins Team Card 73 Buffalo Sabres Team Card 74 Chicago Blackhawks Team Card 75 Cleveland Barons Team Card 76 Colorado Rockies Team Card 77 Detroit Red Wings Team Card 78 Los Angeles Kings Team Card 79 Minnesota North Stars Team Card 80 Montreal Canadiens Team Card 81 New York Islanders Team Card 82 New York Rangers Team Card 83 Philadelphia Flyers Team Card 84 Pittsburgh Penguins Team Card 85 St. -

Sydney Newman, with Contributions by Graeme Burk and a Foreword by Ted Kotcheff

ECW PRESS Fall 2017 ecwpress.com 665 Gerrard Street East General enquiries: [email protected] Toronto, ON M4M 1Y2 Publicity: [email protected] T 416-694-3348 CANADA TABLE OF CONTENTS *HUHKPHU4HUKH.YV\W/LHK6ɉJL FANTASY 664 Annette Street, Toronto, ON M6S 2C8 MUSIC mandagroup.com 1 Bon: The Last Highway 14 Beforelife by Jesse Fink by Randal Graham National Accounts & Ontario Representatives: Joanne Adams, David Farag, TELEVISION YA FANTASY Tim Gain, Jessey Glibbery, Chris Hickey, Peter 2 Head of Drama 15 Scion of the Fox Hill-Field, Anthony Iantorno, Kristina Koski, by Sydney Newman by S.M. Beiko Carey Low, Ryan Muscat, Dave Nadalin, Emily Patry, Nikki Turner, Ellen Warwick 3 A Dream Given Form T 416-516-0911 I`,UZSL`-.\ќL`HUK FICTION [email protected] K. Dale Koontz 16 Malagash by Joey Comeau Quebec & Atlantic Provinces Representative: Jacques Filippi VIDEO GAMES 17 Rose & Poe T 855-626-3222 ext. 244 4 Ain’t No Place for a Hero by Jack Todd QÄSPWWP'THUKHNYV\WJVT by Kaitlin Tremblay 18 Pockets by Stuart Ross Alberta, Saskatchewan & Manitoba Representative: Jean Cichon HUMOUR 5 A Brief History of Oversharing T 403-202-0922 ext. 245 THRILLER by Shawn Hitchins [email protected] 19 The Appraisal by Anna Porter British Columbia NATURE Representatives: 6 The Rights of Nature MYSTERY Iolanda Millar | T 604-662-3511 ext. 246 by David R. Boyd [email protected] 20 Ragged Lake Tracey Bhangu | T 604-662-3511 ext. 247 by Ron Corbett [email protected] BUSINESS 7 Resilience CRIME FICTION Warehouse and Customer Service by Lisa Lisson Jaguar Book Group 21 Zero Avenue 8300 Lawson Road by Dietrich Kalteis SPORTS Milton, ON L9T 0A5 22 Whipped T 905-877-4411 8 Best Canadian by William Deverell Sports Writing Stacey May Fowles 23 April Fool UNITED STATES and Pasha Malla, eds. -

“To Tend Goal for the Greatest Junior Team Ever” – Ted Tucker, Former

“To tend goal for the greatest junior team ever” – Ted Tucker, former California Golden Seals and Montreal Junior Canadiens goalie by Nathaniel Oliver - published on August 30, 2016 Three of them won the Stanley Cup. One is in the Hockey Hall of Fame. Arguably three more should be. Six were NHL All-Star selections. Each one of them played professional hockey, whether it was in the NHL, WHA, or in the minors – they all made it to the pro level. And I am fortunate enough to have one of the two goaltenders for the 1968-69 Montreal Junior Canadiens – the team still widely considered the greatest junior hockey team of all time – to be sharing his story with me. Edward (Ted) William Tucker was born May 7th, 1949 in Fort William, Ontario. From his earliest moments of playing street hockey or shinny, Ted Tucker wanted to be a goaltender. Beginning to play organized hockey at the age of nine, there was minimal opportunity to start the game at a younger age. “At the time that I started playing hockey, there were no Tom Thumb, Mites, or Squirts programs in my hometown. There was a small ad in our local newspaper from the Elks organization, looking for players and asking which position you preferred to play. I asked my parents if I could sign up, and right from the get-go I wanted to be a goalie”. As a youngster, Tucker’s play between the pipes would take some time to develop, though improvement took place each year as he played. -

Jaromir Jagr, the Skater

Jaromir Jagr, the Skater by Ross Bonander January 2014 As a member of The Hockey Writers draft team, I often hear about skating ability from scouts. It tends to be the first thing they look at, although, as Shane Malloy writes in The Art of Scouting, that doesn't mean they all agree on its importance from the scouting perspective. This is in part because, unlike something like size, skating is a skill which players can improve. The 2013-14 season marks Jaromir Jagr’s 25th year of professional hockey, and he is methodically working his way up the all-time scoring lists, all while leading his latest team, the New Jersey Devils, in points. This got me wondering: Perhaps throughout the 1700+ NHL points he’s accumulated, the take-you-out-of-your- seat stickhandling, the jaw-dropping dekes and sensational goals, maybe one aspect of Jagr's game deserved a closer look. Jaromir Jagr, the Skater. The great Eddie Johnston once echoed a sentiment expressed by everyone from Mario Lemieux to Scotty Bowman when he said: “I don’t know any player who is stronger on his skates than Jaromir Jagr. One on one, there has never been a player so dangerous.” For instance, in collecting his 1,723rd career point, an assist on an Adam Henrique goal, Jaromir Jagr victimized defenseman Nick Grossman in classic Jagr fashion: With fast hands, long reach, impeccable hockey sense … and all of it powered from, made possible by, his skates. After watching video both new and old, I concluded that for all the spectacular goals Jagr has scored, almost none of them would be possible were he anything short of one of the very best skaters in the game. -

Goaltending Newsletter

Goaltending Newsletter Prepared for Marblehead Youth Hockey By Joe Bertagna, Bertagna Goaltending Issue #5 - November 12, 2014 What does it mean to “know how to play goal”? Many years ago, I walked out of a college hockey game in which the goalie made close to 50 saves in an acrobatic performance, winning the contest by a 4-3 score. An NHL scout who left the game along side of me remarked, “That goalie is pretty good. He will be even better when he learns how to play the position.” I wasn’t sure what he meant at the time. How could the guy make all those saves and not know “how to play the position”? All these years later, I think I understand the distinction. Some goalies, particularly at younger levels, can succeed on the strength of pure athleticism and reflexes. Eventually, the shooters against which we play will get better. Their shots will be harder and more accurate. Their release better disguised. Try- ing to succeed by waiting and simply beating the puck to an open space will prove more challenging against bantams and beyond. Goalies in our area are fortunate to have a variety of options when it comes to finding goalie coaches. But can you find one who teaches more than technique? Learning a series of techniques is important but it is not the same as learning how to play goal. There is a mental component, a strategy component, that is key. A goalie has to know which techniques to employ and when. And more to the point of this essay, the goalie has to see the game in such a way that he reads or antici- pates what is about to happen. -

A Matter of Inches My Last Fight

INDEPENDENT PUBLISHERS GROUP A Matter of Inches How I Survived in the Crease and Beyond Clint Malarchuk, Dan Robson Summary No job in the world of sports is as intimidating, exhilarating, and stressridden as that of a hockey goaltender. Clint Malarchuk did that job while suffering high anxiety, depression, and obsessive compulsive disorder and had his career nearly literally cut short by a skate across his neck, to date the most gruesome injury hockey has ever seen. This autobiography takes readers deep into the troubled mind of Clint Malarchuk, the former NHL goaltender for the Quebec Nordiques, the Washington Capitals, and the Buffalo Sabres. When his carotid artery was slashed during a collision in the crease, Malarchuk nearly died on the ice. Forever changed, he struggled deeply with depression and a dependence on alcohol, which nearly cost him his life and left a bullet in his head. Now working as the goaltender coach for the Calgary Flames, Malarchuk reflects on his past as he looks forward to the future, every day grateful to have cheated deathtwice. 9781629370491 Pub Date: 11/1/14 Author Bio Ship Date: 11/1/14 Clint Malarchuk was a goaltender with the Quebec Nordiques, the Washington Capitals, and the Buffalo Sabres. $25.95 Hardcover Originally from Grande Prairie, Alberta, he now divides his time between Calgary, where he is the goaltender coach for the Calgary Flames, and his ranch in Nevada. Dan Robson is a senior writer at Sportsnet Magazine. He 272 pages lives in Toronto. Carton Qty: 20 Sports & Recreation / Hockey SPO020000 6.000 in W | 9.000 in H 152mm W | 229mm H My Last Fight The True Story of a Hockey Rock Star Darren McCarty, Kevin Allen Summary Looking back on a memorable career, Darren McCarty recounts his time as one of the most visible and beloved members of the Detroit Red Wings as well as his personal struggles with addiction, finances, and women and his daily battles to overcome them. -

Dan Bouchard

Dan Bouchard A member of the Sorel Black Hawks in 1968-69, Dan Bouchard guided his team to the 1969 Memorial Cup tournament before playing one season with the London Knights of the OHA-Jr league. After a two-year stint in the AHL where he was an AHL First Team All-Star with the Boston Braves and a one game stint in the CHL with the Oklahoma City Blazers, Bouchard was claimed by the fledgling Atlanta Flames where, after enduring the growth pains of expansion, he consistently won more games than he lost, year in and year out. Dan credits his longevity, which consisted of 14 NHL seasons, to some useful advice given by Frank Mahovlich. In Bouchard's first-ever NHL start, the Big M popped a slapper past the rookie netminder and while cruising past the net said, "One of many, kid. One of many!" Thanks to Big Frank, Bouchard learned to live with conceding goals while coveting victories. By 1981, Bouchard was traded to the Quebec Nordiques where he savoured many more wins in the company of a talent-laden squad that set new battle lines across the province of Quebec. The Montreal Canadiens had a serious rival on their hands and Bouchard was there to glove most of the bullets. Dan concluded his NHL career in 1986 with the Winnipeg Jets. From there, he played for three weeks in Switzerland before a serious knee injury put him on the shelf for good. After packing away his pads, Bouchard served as a goaltending coach for the Nordiques. -

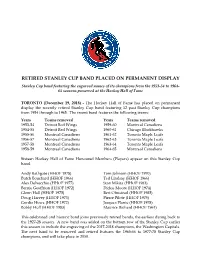

Retired Stanley Cup Band Placed on Permanent Display

RETIRED STANLEY CUP BAND PLACED ON PERMANENT DISPLAY Stanley Cup band featuring the engraved names of its champions from the 1953-54 to 1964- 65 seasons preserved at the Hockey Hall of Fame TORONTO (December 19, 2018) - The Hockey Hall of Fame has placed on permanent display the recently retired Stanley Cup band featuring 12 past Stanley Cup champions from 1954 through to 1965. The recent band features the following teams: Years Teams removed Years Teams removed 1953-54 Detroit Red Wings 1959-60 Montreal Canadiens 1954-55 Detroit Red Wings 1960-61 Chicago Blackhawks 1955-56 Montreal Canadiens 1961-62 Toronto Maple Leafs 1956-57 Montreal Canadiens 1962-63 Toronto Maple Leafs 1957-58 Montreal Canadiens 1963-64 Toronto Maple Leafs 1958-59 Montreal Canadiens 1964-65 Montreal Canadiens Sixteen Hockey Hall of Fame Honoured Members (Players) appear on this Stanley Cup band. Andy Bathgate (HHOF 1978) Tom Johnson (HHOF 1970) Butch Bouchard (HHOF 1966) Ted Lindsay (HHOF 1966) Alex Delvecchio (HHOF 1977) Stan Mikita (HHOF 1983) Bernie Geoffrion (HHOF 1972) Dickie Moore (HHOF 1974) Glenn Hall (HHOF 1975) Bert Olmstead (HHOF 1985) Doug Harvey (HHOF 1973) Pierre Pilote (HHOF 1975) Gordie Howe (HHOF 1972) Jacques Plante (HHOF 1978) Bobby Hull (HHOF 1983) Maurice Richard (HHOF 1961) This celebrated and historic band joins previously retired bands, the earliest dating back to the 1927-28 season. A new band was added on the bottom row of the Stanley Cup earlier this season to include the engraving of the 2017-2018 champions, the Washington Capitals. The next band to be removed and retired features the 1965-66 to 1977-78 Stanley Cup champions, and will take place in 2030. -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 5/23/2021 Boston Bruins Edmonton Oilers 1213787 John Tavares has concussion, knee injury; likely to miss 1213818 Those who criticized frontline workers for being at Oilers series playoff game need to give their heads a shake 1213788 Capitals’ Dmitry Orlov not fined for high hit on the Bruins’ 1213819 Edmonton Oilers are bleeding heavily, but they're not Kevan Miller in Game 4 dead yet 1213789 Former Canadien Gilles Lupien’s path to the NHL was a 1213820 Down 0-2, Edmonton Oilers not about to abandon playoff road rarely traveled these days ship 1213790 ‘He’s one of the best defensemen in the league.’ Charlie 1213821 All-Canadian playoff division the experience of a lifetime McAvoy was at the center of the Bruins’ big win in Ga for Oilers 1213791 Bruins Notebook: B’s hope to oust Capitals 1213822 NHL picks today: Expert predictions, odds for 1213792 Boston Bruins D Kevan Miller Out For Game 5 Capitals-Bruins, Hurricanes-Predators, Jets-Oilers and 1213793 Boston Bruins Put Capitals On Lockdown With Game 4 Avalanche Win |BHN+ 1213823 The 5 biggest stories from the Bakersfield Condors’ 1213794 NHL picks today: Expert predictions, odds for 2020-21 season Capitals-Bruins, Hurricanes-Predators, Jets-Oilers and Avalanche Florida Panthers 1213795 How will Kevan Miller’s injury affect the Bruins in Game 5? 1213824 Inside the Panthers’ goalie debate: Bobrovsky, Driedger or 1213796 He can win it for them’: Gerry Cheevers salutes Tuukka Knight for must-win Game 5? Rask after goalie claims Bruins record for playoff wins 1213825 -

An Educational Experience

INTRODUCTION An Educational Experience In many countries, hockey is just a game, but to Canadians it’s a thread woven into the very fabric of our society. The Hockey Hall of Fame is a museum where participants and builders of the sport are honoured and the history of hockey is preserved. Through the Education Program, students can share in the glory of great moments on the ice that are now part of our Canadian culture. The Hockey Hall of Fame has used components of the sport to support educational core curriculum. The goal of this program is to provide an arena in which students can utilize critical thinking skills and experience hands-on interactive opportunities that will assure a successful and worthwhile field trip to the Hockey Hall of Fame. The contents of this the Education Program are recommended for Grades 6-9. Introduction Contents Curriculum Overview ……………………………………………………….… 2 Questions and Answers .............................................................................. 3 Teacher’s complimentary Voucher ............................................................ 5 Working Committee Members ................................................................... 5 Teacher’s Fieldtrip Checklist ..................................................................... 6 Map............................................................................................................... 6 Evaluation Form……………………............................................................. 7 Pre-visit Activity ....................................................................................... -

1987 SC Playoff Summaries

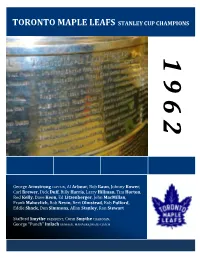

TORONTO MAPLE LEAFS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 1 9 6 2 George Armstrong CAPTAIN, Al Arbour, Bob Baun, Johnny Bower, Carl Brewer, Dick Duff, Billy Harris, Larry Hillman, Tim Horton, Red Kelly, Dave Keon, Ed Litzenberger, John MacMillan, Frank Mahovlich, Bob Nevin, Bert Olmstead, Bob Pulford, Eddie Shack, Don Simmons, Allan Stanley, Ron Stewart Stafford Smythe PRESIDENT, Conn Smythe CHAIRMAN, George “Punch” Imlach GENERAL MANAGER/HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 1962 STANLEY CUP SEMI-FINAL 1 MONTRÉAL CANADIENS 98 v. 3 CHICAGO BLACK HAWKS 75 GM FRANK J. SELKE, HC HECTOR ‘TOE’ BLAKE v. GM TOMMY IVAN, HC RUDY PILOUS BLACK HAWKS WIN SERIES IN 6 Tuesday, March 27 Thursday, March 29 CHICAGO 1 @ MONTREAL 2 CHICAGO 3 @ MONTREAL 4 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD NO SCORING 1. CHICAGO, Bobby Hull 1 (Bill Hay, Stan Mikita) 5:26 PPG 2. MONTREAL, Dickie Moore 2 (Bill Hicke, Ralph Backstrom) 15:10 PPG Penalties – Moore M 0:36, Horvath C 3:30, Wharram C Fontinato M (double minor) 6:04, Fontinato M 11:00, Béliveau M 14:56, Nesterenko C 17:15 Penalties – Evans C 1:06, Backstrom M 3:35, Moore M 8:26, Plante M (served by Berenson) 9:21, Wharram C 14:05, Fontinato M 17:37 SECOND PERIOD NO SCORING SECOND PERIOD 3. -

1969-70 Topps Hockey Card Checklist+A1

1 969-70 TOPPS HOCKEY CARD CHECKLIST+A1 1 Gump Worsley 2 Ted Harris 3 Jacques Laperriere 4 Serge Savard 5 J.C. Tremblay 6 Yvan Cournoyer 7 John Ferguson 8 Jacques Lemaire 9 Bobby Rousseau 10 Jean Beliveau 11 Henri Richard 12 Glenn Hall 13 Bob Plager 14 Jim Roberts 15 Jean-Guy Talbot 16 Andre Boudrias 17 Camille Henry 18 Ab McDonald 19 Gary Sabourin 20 Red Berenson 21 Phil Goyette 22 Gerry Cheevers 23 Ted Green 24 Bobby Orr 25 Dallas Smith 26 Johnny Bucyk 27 Ken Hodge 28 John McKenzie 29 Ed Westfall 30 Phil Esposito 31 Derek Sanderson 32 Fred Stanfield 33 Ed Giacomin 34 Arnie Brown 35 Jim Neilson 36 Rod Seiling 37 Rod Gilbert 38 Vic Hadfield 39 Don Marshall 40 Bob Nevin 41 Ron Stewart 42 Jean Ratelle Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Walter Tkaczuk 44 Bruce Gamble 45 Tim Horton 46 Ron Ellis 47 Paul Henderson 48 Brit Selby 49 Floyd Smith 50 Mike Walton 51 Dave Keon 52 Murray Oliver 53 Bob Pulford 54 Norm Ullman 55 Roger Crozier 56 Roy Edwards 57 Bob Baun 58 Gary Bergman 59 Carl Brewer 60 Wayne Connelly 61 Gordie Howe 62 Frank Mahovlich 63 Bruce MacGregor 64 Alex Delvecchio 65 Pete Stemkowski 66 Denis DeJordy 67 Doug Jarrett 68 Gilles Marotte 69 Pat Stapleton 70 Bobby Hull 71 Dennis Hull 72 Doug Mohns 73 Jim Pappin 74 Ken Wharram 75 Pit Martin 76 Stan Mikita 77 Charlie Hodge 78 Gary Smith 79 Harry Howell 80 Bert Marshall 81 Doug Roberts 82 Carol Vadnais 83 Gerry Ehman 84 Bill Hicke 85 Gary Jarrett 86 Ted Hampson 87 Earl Ingarfield 88 Doug Favell 89 Bernie Parent Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 2 90 Larry Hillman