The Social Function of Property and the Human Capacity to Flourish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LL Parsing Objectives What Is LL(N) Parsing? What Is LL(N

Introduction LL Parsing Breaking LL Parsers Introduction LL Parsing Breaking LL Parsers Objectives LL Parsing The topic for this lecture is a kind of grammar that works well with recursive-descent parsing. Classify a grammar as being LL or not LL. Dr. Mattox Beckman I I Use recursive-descent parsing to implement an LL parser. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Explain how left-recursion and common prefixes defeat LL parsers. Department of Computer Science I Introduction LL Parsing Breaking LL Parsers Introduction LL Parsing Breaking LL Parsers What Is LL(n) Parsing? What Is LL(n) Parsing? I An LL parse uses a Left-to-right scan and produces a Leftmost derivation, using n tokens I An LL parse uses a Left-to-right scan and produces a Leftmost derivation, using n tokens of lookahead. of lookahead. I A.k.a. top-down parsing I A.k.a. top-down parsing Example Grammar: Syntax Tree: Example Grammar: Syntax Tree: S S S + EE S + EE → → E int E int → + E E E→ EE E EE →∗ →∗ Example Input: Example Input: + 2 * 3 4 + 2 * 3 4 Introduction LL Parsing Breaking LL Parsers Introduction LL Parsing Breaking LL Parsers What Is LL(n) Parsing? What Is LL(n) Parsing? I An LL parse uses a Left-to-right scan and produces a Leftmost derivation, using n tokens I An LL parse uses a Left-to-right scan and produces a Leftmost derivation, using n tokens of lookahead. of lookahead. I A.k.a. top-down parsing I A.k.a. top-down parsing Example Grammar: Syntax Tree: Example Grammar: Syntax Tree: S S S + EE S + EE → → E int + E E E int + E E E→ EE E→ EE →∗ →∗ Example Input: 2 Example Input: 2 * E E + 2 * 3 4 + 2 * 3 4 Introduction LL Parsing Breaking LL Parsers Introduction LL Parsing Breaking LL Parsers What Is LL(n) Parsing? What Is LL(n) Parsing? I An LL parse uses a Left-to-right scan and produces a Leftmost derivation, using n tokens I An LL parse uses a Left-to-right scan and produces a Leftmost derivation, using n tokens of lookahead. -

I(Il Ll:N Cit~ BEFORE the BOARD of HEALING ARTS AUG 2 6 2010 of the STATE of KANSAS

i(iL ll:n Cit~ BEFORE THE BOARD OF HEALING ARTS AUG 2 6 2010 OF THE STATE OF KANSAS In the Matter of ) ) DocketNo. 11-HA 000A5 Michael Todd Hanson, R.T. ) Kansas License No. Pending ) CONSENT ORDER COMES NOW, the Kansas State Board of Healing Arts, ("Board"), by and through Stacy R. Bond, Associate Litigation Counsel ("Petitioner"), and Michael Todd Hanson, R.T. ("Applicant") and move the Board for approval of a Consent Order affecting Applicant's license to practice respiratory therapy in the State of Kansas. The Parties stipulate and agree to the following: 1. Applicant's last known mailing address to the Board is: P.O. Box 66, Stewartsville, Missouri 64490. 2. On or about May 4, 2010, Applicant submitted to the Board an application for licensure in respiratory therapy. Such application was deemed complete on July 15, 2010. 3. The Board is the sole and exclusive administrative agency in the State of Kansas authorized to regulate the practice of the healing arts, specifically the practice of respiratory therapy. K.S.A. 65-5501 et seq. and K.S.A. 65-5502. 4. This Consent Order and the filing of such document are in accordance with applicable law and the Board has jurisdiction to enter into the Consent Order as provided by K.S.A. 77-505 and 65-2838. Upon approval, these stipulations shall Consent Order Michael Todd Hanson, R.T. Page 1 of 13 constitute the findings of the Board, and this Consent Order shall constitute the Board's Final Order. 5. The Kansas Respiratory Therapy Practice Act is constitutional on its face and as applied in the case. -

Reminiscences of Red Hook" in November, 1926

Reminiscences of Red Hook (A story of the Village) by Edmund Bassett Edmund Bassett was born in Red Hook about 1865. He studied telegraphy and held various positions with the New York Central Railroad, among them Stationmaster at Tivoli. Later in life he went to New York City where he was very successful. Like most people who move to a big city life in a small town is remembered with great fondness. Mr. Bassett was no exception and these reminiscences were an expression of his feeling. Mr. Bassett started his "Reminiscences of Red Hook" in November, 1926. These were published weekly over a period of three months in the REV HOOK AVVERTISER. The second series, "Reminisoenoes of Some of the Highways and Byways of Red Hook" were written in 1928 and published in the REV HOOK AVVERTISER over a period of several months from April 10, 1930 to October 9, 1930. By using the enclosed 1867 map of the Village of Red Hook, it is possible to follow Mr. Bassett's travels.and identify families, buildings, and streets mentioned in the articles. Reprinted June 1976 by Red Hook-Tivoli Bicentennial Committee REMINISCENCES OF RED HOOK By Edmund Bassett As good "Americans" we should love our native country, but no part of same is so dear to me as Red Hook, the spot where I first saw the light of day. We should all follow the commandment, "Love your neighbor as yourself" and all men are our neighbors; but the poor and down trodden should ever have a special appeal to us, and they do; but the old neighbors at home, in dear old Red Hook, have an appeal all their own to me. -

Lexia Lessons Digraph Ch

® LEVEL 6 | Phonics Lexia Lessons Digraph ch Description This lesson is designed to reinforce letter-sound correspondence for the consonant digraph ch, where the two letters, c-h, represent one sound, /ch/. Knowledge of consonant digraphs will improve students’ ability to apply phonic word attack strategies for reading and spelling. TEACHER TIPS The following steps show a lesson in which students identify the sound /ch/ at the beginning of words and match the sound to the letters c-h. For students who have difficulty distinguishing the stop sound /ch/ from the continuant sound /sh/, place emphasis on the stop sound of /ch/ by repeating it while making an abrupt chopping motion with your arm: /ch/ /ch/ /ch/. PREPARATION/MATERIALS • For each student, a card or sticky note • A copy of the ch Keyword Image Card and with the digraph ch printed on it 9 pictures at the end of the lesson • Blank sticky notes Primary Standard: CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RF.1.3a - Know the spelling-sound - Know Standard: CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RF.1.3a Primary correspondences for common consonant digraphs. Warm-up Use a phonemic awareness activity to review how to isolate the initial sound /ch/. ListenasIsayawordintwoparts:/ch/op.Thefirstsoundis/ch/.Theendingsoundsareop.WhenI putthemtogether,Igetthewordchop.Whatisthefirstsoundinchop?(/ch/) Make a single chopping motion with one arm. Thesound/ch/isthesoundwehearatthebeginningofthewordchop.Let’sallsay/ch/together:/ ch//ch//ch/.I’mgoingtosayaword.Ifthewordbeginswith/ch/,chopwithyourhandlikethisand say/ch/.Iftheworddoesnotbeginwith/ch/,keepyourhanddownandmakenosound. Suggested words: chill, chest, time, jump, chain, treasure, gentle, chocolate. Direct Instruction Reading. ® Display the Keyword Image Card of the cheese with the ch on it. -

CM Lodestar Manual

Provided by: www.hoistsdirect.com Operating, Maintenance & Parts Manual ® Rated Loads 1/8 through 3-Tons/ 125 kg through 3000 kg. Follow all instructions and warnings for inspecting, maintaining and operating this hoist. The use of any hoist presents some risk of personal injury or property damage. That risk is greatly increased if proper instructions and warnings are not followed. Before using this hoist, each operator should become thoroughly familiar with all warnings, instructions, and recommendations in this manual. Retain this manual for future reference and use. Forward this manual to the hoist operator. Failure to operate the equipment as directed in the manual may cause injury. Before using the hoist, fill in the information below. Refer to the hoist identification plate. Model Number ____________________________ Serial Number ____________________________ Purchase Date ____________________________ Voltage __________________________________ Rated Load ______________________________ Electric Chain 83874 627-Q i CM HOIST PARTS AND SERVICES ARE AVAILABLE IN THE UNITED STATES AND IN CANADA As a CM Hoist user, you are assured of reliable repair and parts services through a network of Master Parts Depots and Service Centers that are strategically located in the United States and Canada. These facilities have been selected on the basis of their demonstrated ability to handle all parts and repair requirements promptly and efficiently. Below is a list of the Master Parts Depots in the United States and Canada. To quickly obtain the name of the U.S. Service Center located nearest you, call (800) 888-0985. Fax: (716) 689-5644. In the following list, the Canadian Service Centers are indicated. UNITED STATES MASTER PARTS DEPOT CANADIAN SERVICE CENTERS CALIFORNIA NEW YORK ALBERTA OTTO SYSTEMS, INC. -

ZTR6200-LL-X-W2 Connected Aquasense® Sensor Operated Battery Powered Retrofit Kit for Water Closet TAG ______

ZTR6200-LL-X-W2 Connected AquaSense® Sensor Operated Battery Powered Retrofit Kit for Water Closet TAG ____________ Architectural/Engineering Specification: Zurn Connected Flush Valves transmit data 24/7 to the Zurn plumbSMART™* web portal and mobile app. Proactively monitor your flush activations and water usage, receive real-time alerts for preset high and low usage parameters, and access system data for trends and predictive maintenance anytime and anywhere. AquaSense® Sensor Flush Valves are ideal for high-use applications where durability and hands-free operation are necessary. ADA compliant, battery powered, sensor operated for retrofit and new construction. Unit is furnished with a clog resistant piston and manual override button. Inluded as standard are 4 “AA” Long Life Lithium batteries. Product Features: Flow Options: PlumbSMART™ Portal • Know water consumption • Track uses per fixture • Receive real-time alerts • Manage maintenance tasks • Receive insights on your data Flush Volume gpf [Lpf] Dual Flush WaterSense Labeled* • Integrate data into BMS through BACnet gateway -ONE 1.1 gpf [4.1 Lpf] Flush Valve -EV 1.28 gpf [4.8 Lpf] • Proprietary dezincification resistant low lead brass alloy • Chloramine resistant Internal seals -WS1 1.6 gpf [6.1 Lpf] 1.6/1.1 gpf [6.1/4.1 Lpf] Technical Specification: Flush Valve Suffix Options: • 4 “AA” Lithium batteries (included) • 3 years battery life shared with endpoint -DF Dual Flush Option (See Chart Above) Connected Endpoint Gateway Options: • 4 “AA” Lithium batteries (included) • 3 years battery life shared with flush valve (Required & Sold Separately) • Communicates wirelessly to Zurn gateway -LTE ZGW-LORA-W1-LTE Zurn Gateway: -Ethernet ZGW-LORA-W1-ETH • Communicates via Ethernet or LTE Note: plumbSMART™ is free-to-connect to a basic plan • Works with all Zurn connected devices with an option to upgrade to a premium plan. -

Phonics TRB Coding Chart

Coding Charts The following coding charts briefly explain vowel and spelling rules, syllable-division patterns, letter clusters, and coding marks used in Saxon’s phonics programs. Basic Coding TO CODE USE EXAMPLE Accented syllables Accent marks noÆ C ’s that make a /k/ sound, as in “cat” K-backs |cat C ’s that make a /s/ sound, as in “cell” Cedillas çell Combinations; diphthongs Arcs ar™ Digraphs; trigraphs; quadrigraphs Underlines SH___ Final, stable syllables Brackets [fle Long vowel sounds Macrons nO Schwa vowel sounds (rhymes with vowel sound in “sun,” as Schwas o÷ (or ) in “some,” “about,” and “won”) Short vowel sounds Breves log Sight words Circles ≤are≥ Silent letters Slash marks mak´ Affixes Boxes work ingfl Syllables Syllable division lines cac\tus Voiced sounds Voice lines hiß Vowel Rules RULE CODING EXAMPLE A vowel followed by a consonant is short; code it logcatsit with a breve. An open, accented vowel is long; code it with a nOÆ mEÆ íÆ gOÆ macron. AÆ\|cor™n OÆ\p»n EÆ\v»n A vowel followed by a consonant and a silent e is long; code the vowel with a macron and cross out the nAm´ hOp´ lIk´ silent e. An open, unaccented vowel can make a schwa b«\nanÆ\« E\rAs´Æ hO\telÆ sound. The letters e, o, and u can also make a long sound. The letter i can also make a short sound. JU\lŒÆ di\vId´Æ Copyright by Saxon Publishers, Inc. Spelling Rules† RULE EXAMPLE Floss Rule: When a one-syllable root word has a short vowel sound followed by the sound /f/, /l/, or /s/, it is puff doll pass usually spelled ff, ll, or ss. -

Instructions for Form IT-204-LL Partnership, Limited

Department of Taxation and Finance Instructions for Form IT-204-LL IT-204-LL-I Partnership, Limited Liability Company, and Limited Liability Partnership Filing Fee Payment Form Note: You may be able to e-file this form through your tax Fee for payments returned by banks – The law allows the Tax preparation software. A complete list of personal income tax forms Department to charge a $50 fee when a check, money order, or that can be e-filed is provided on our website at www.tax.ny.gov. electronic payment is returned by a bank for nonpayment. However, if an electronic payment is returned as a result of an error by the bank or the department, the department won’t charge the fee. If your General information payment is returned, we will send a separate bill for $50 for each Who must file return or other tax document associated with the returned payment. Form IT-204-LL, Partnership, Limited Liability Company, and Limited Liability Partnership Filing Fee Payment Form, must be filed by Additional filing requirements every: • Both domestic LLCs and LLPs are required to register with the • limited liability company (LLC) that is a disregarded entity for New York State Department of State. In addition, foreign LLCs federal income tax purposes that has income, gain, loss, or and LLPs that wish to carry on or conduct business or activities deduction from New York State sources; and in New York State must also register with the Department of State. Taxpayers who have questions concerning the • domestic or foreign LLC (including a limited liability investment registration process should visit the Department of State website company (LLIC) or a limited liability trust company (LLTC)), or (www.dos.ny.gov), write to the New York State Department limited liability partnership (LLP) that is required to file a New of State, One Commerce Plaza, 99 Washington Avenue, York State partnership return and that has income, gain, loss, or Albany NY 12231-0001, or call 518-473-2492. -

Ll. C:'/L C/1 V I I

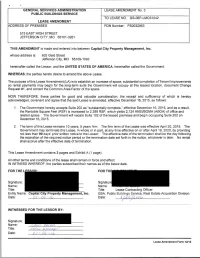

GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION LEASE AMENDMENT No. 3 PUBLIC BUILDINGS SERVICE TO LEASE NO. GS-06P-LM031042 LEASE AMENDMENT ~DDRESS OF PREMISES PON Number: PS0032863 515 EAST HIGH STREET JEFFERSON CITY, MO 65101-3261 THIS AMENDMENT is made and entered into between Capital City Property Management, Inc. whose address is: 602 Geld Street Jefferson City, MO 65109-1093 hereinafter called the Lessor, and the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, hereinafter called the Government: WHEREAS, the parties hereto desire to amend the above Lease. The purpose of this Lease Amendment (LA) is to establish an increase of space, substantial completion of Tenant Improvements so rental payments may begin for the long-term suite the Government will occupy at this leased location, document Change Request #1 , and correct the Common Area Factor of the space. NOW THEREFORE, these parties for good and valuable consideration, the receipt and sufficiency of which is hereby acknowledged, covenant and agree that the said Lease is amended, effective December 16, 2015, as follows: 1. The Government hereby accepts Suite 202 as "substantially complete," effective December 16, 2015, and as a result, the Rentable Square Feet (RSF) is increased to 2,399 RSF, which yields 2, 124 ANSl/BOMA (ABOA) of office and related space. The Government will vacate Suite 102 of the leased premises and begin occupying Suite 202 on December 16, 2015. 2. The term of this Lease remains 10 years, 5 years firm . The firm term of the Lease was effective April 20, 2015. The Government may terminate this Lease, in whole or in part, at any time effective on or after April 19, 2020, by providing not less than 90 days' prior written notice to the Lessor. -

Digraph Sh Whiteboard Activities See Instructional Routines, Pages 29–32, for Additional Lesson Details and Support

IWB Interactive Digraph sh Whiteboard Activities See Instructional Routines, pages 29–32, for additional lesson details and support. IWB This icon indicates that the CD includes an interactive whiteboard version of the activity that can be used for small-group or whole-class learning. Introduce the Sound-Spelling: Tell children that when the letters s 1 and h appear together in a word, they usually stand for a new sound—the /sh/ sound. Write the letters sh on the board. Have children write the letters sh several Build Words times as they say /sh/. Model Blending: Write the words hop, shop, sell, shell, dish, trash, and 2 splash on the board. Model blending the words sound by sound. Run your finger under each letter as you say the sound. Emphasize the sound ofsh in words containing that digraph spelling. Have children repeat. Blend Words: Use Blend Words: Digraph sh, page 242, to have children Sound-Spelling Word Sort 3 chorally blend the words on each line. Model, as needed. Children can then use the lists for further independent practice. Also encourage children to complete the Do More! activities. Build Words: Using the letter cards on Build Words: Digraph sh, page 243, 4 have children build the following words in sequence: hot, shot, shop, hop, hip, ship, sip, sick, sock, shock, shack, back, bat, fat, fit, fish, wish, dish, dash, rash, rush. Spell Words Then have children complete the activities on the page. IWB Sort Words: Use Sound-Spelling Word Sort: Digraph sh, page 244, to have 5 children work with partners to sort the words by their sound-spellings. -

Ll-N-17 To: Alexander, Kerry Subject: Contractor 58 Fay St Attachments: D O C0 5 8 3 3 520L7 LL02IL0 602.P Df

From: Ouellette, David Sent: Monday, November 06,20L7 9:34 AM lL-n-17 To: Alexander, Kerry Subject: Contractor 58 Fay St Attachments: d o c0 5 8 3 3 520L7 LL02IL0 602.p df Atl This is the report from the contractor on the roof issue for 58 Fay Street. This letter is approved by the Building Commissioner Shaun Shanahan has resulting the question of mold or any issues in the attic area. The only items left is stain kill and paint ceilings in bedrooms that is not a health hazard only cosmetic. The bathroom area has been repaired only needs sanding and final coat of paint, All other items have been addressed please see other email with pictures from the landlord and contractor. The tenant has not been pro-active and the landlord needed to call the police to get access. Ilnvorce pErES HANDv MAN sEnfr/rcEs l"?11;" *"., 1{::trtt' 240 Merrimack St. Manchester NH 03103 Due Date: 11 t27t2717 6m-82e2889 Bill To: Ship To: Tamara Record Tamara Record Tamara Record 58 Fay Street unit 4 58 Fay Street unit 4 Lowell MA Lowell MA Hrc Description Unit Price Total 1 Inspection of attic: I found the attic to be dry and in good shape there \iras one spot where the insullation was pulled back and a towel in itrs place lt appears this has been like this for some time there was no utet spots or any sign of a current leak just some old etaining I put the insullation back in its place and inspected the outside of the roof 1 Inspection of roof: I found that the roof is older but no signs of any curet leaks or soft spots the.neighboring roof was rgplaced and shingles -

LL-2021-03) Updated: Aug

Lender Letter (LL-2021-03) Updated: Aug. 11, 2021 To: All Fannie Mae Single-Family Sellers Impact of COVID-19 on Originations This Lender Letter contains the policies previously published in LL-2020-03 on Dec. 10, 2020, with the changes noted below. We are continuing to collaborate with FHFA and Freddie Mac and will update and republish this Lender Letter as necessary. Aug. 11 . Effective immediately we are retiring the age of documentation and market-based asset policies that have been in place . Removed from this Lender Letter the verbal verification of employment policy that previously expired and the power of attorney policy that was moved to the Selling Guide Note that we will also be reinstating representation and warranty relief for employment validation within the DU validation service in a future release. All remaining policies in this Lender Letter continue to be effective until further notice. Mar. 11 . Extending the application dates for verbal verifications of employment and power of attorney flexibilities to Apr. 30, 2021. This will be the final extension for these policies. Applications dated May 1, 2021 and later will be subject to standard Selling Guide policies. Feb. 10 . Extending the application dates for verbal verifications of employment and power of attorney flexibilities to Mar. 31, 2021 Jan. 14 . Extending the application dates for verbal verifications of employment and power of attorney flexibilities to Feb. 28, 2021 . Content was reorganized such that the policies with explicit expiration dates are shown first, and like content was moved closer together (income and employment). Content that no longer applies was removed (such as quality control flexibilities and submission of financial statements), as have reminders of current policies in the Selling Guide.