Penetration of Dutch Colonial Power Against the Sultanate of Jambi, 1615-1904

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendices 2011–12

Art GAllery of New South wAleS appendices 2011–12 Sponsorship 73 Philanthropy and bequests received 73 Art prizes, grants and scholarships 75 Gallery publications for sale 75 Visitor numbers 76 Exhibitions listing 77 Aged and disability access programs and services 78 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs and services 79 Multicultural policies and services plan 80 Electronic service delivery 81 Overseas travel 82 Collection – purchases 83 Collection – gifts 85 Collection – loans 88 Staff, volunteers and interns 94 Staff publications, presentations and related activities 96 Customer service delivery 101 Compliance reporting 101 Image details and credits 102 masterpieces from the Musée Grants received SPONSORSHIP National Picasso, Paris During 2011–12 the following funding was received: UBS Contemporary galleries program partner entity Project $ amount VisAsia Council of the Art Sponsors Gallery of New South Wales Nelson Meers foundation Barry Pearce curator emeritus project 75,000 as at 30 June 2012 Asian exhibition program partner CAf America Conservation work The flood in 44,292 the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit ANZ Principal sponsor: Archibald, Japan foundation Contemporary Asia 2,273 wynne and Sulman Prizes 2012 President’s Council TOTAL 121,565 Avant Card Support sponsor: general Members of the President’s Council as at 30 June 2012 Bank of America Merill Lynch Conservation support for The flood Steven lowy AM, Westfield PHILANTHROPY AC; Kenneth r reed; Charles in the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit Holdings, President & Denyse -

Daftar 34 Provinsi Beserta Ibukota Di Indonesia

SEKRETARIAT UTAMA LEMHANNAS RI BIRO KERJASAMA DAFTAR 34 PROVINSI BESERTA IBUKOTA DI INDONESIA I. PULAU SUMATERA 1. Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam : Banda Aceh 2. Sumatera Utara : Medan 3. Sumatera Selatan : Palembang 4. Sumatera Barat : Padang 5. Bengkulu : Bengkulu 6. Riau : Pekanbaru 7. Kepulauan Riau : Tanjung Pinang 8. Jambi : Jambi 9. Lampung : Bandar Lampung 10. Bangka Belitung : Pangkal Pinang II. PULAU KALIMANTAN 1. Kalimantan Barat : Pontianak 2. Kalimantan Timur : Samarinda 3. Kalimantan Selatan : Banjarmasin 4. Kalimantan Tengah : Palangkaraya 5. Kalimantan Utara : Tanjung Selor (Belum pernah melkskan MoU) III. PULAU JAWA 1. Banten : Serang 2. DKI Jakarta : Jakarta 3. Jawa Barat : Bandung 4. Jawa Tengah : Semarang 5. DI Yogyakarta : Yogyakarta 6. Jawa timur : Surabaya IV. PULAU NUSA TENGGARA & BALI 1. Bali : Denpasar 2. Nusa Tenggara Timur : Kupang 3. Nusa Tenggara Barat : Mataram V. PULAU SULAWESI 1. Gorontalo : Gorontalo 2. Sulawesi Barat : Mamuju 3. Sulawesi Tengah : Palu 4. Sulawesi Utara : Manado 5. Sulawesi Tenggara : Kendari 6. Sulawesi Selatan : Makassar VI. PULAU MALUKU & PAPUA 1. Maluku Utara : Ternate 2. Maluku : Ambon 3. Papua Barat : Manokwari 4. Papua ( Daerah Khusus ) : Jayapura *) Provinsi Terbaru Prov. Teluk Cendrawasih (Seruai) *) Provinsi Papua Barat (Sorong) 2 DAFTAR MoU DI LEMHANNAS RI Pemerintah/Non Pemerintah, BUMN/Swasta, Parpol, Ormas & Universitas *) PROVINSI 1. Gub. Aceh-10/5 16-11-2009 2. Prov. Sumatera Barat-11/5 08-12-2009 Prov. Sumbar-116/12 16-12-2015 3. Prov. Kep Riau-12/5 21-12-2009 Kep. Riau-112/5 16-12-2015 4. Gub. Kep Bangka Belitung-13/5 18-11-2009 5. Gub. Sumatera Selatan-14 /5 16-11-2009 Gub. -

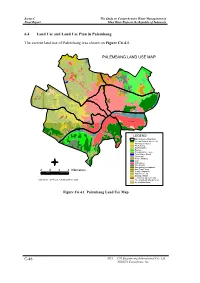

C-46 6.4 Land Use and Land Use Plan in Palembang the Current Land Use of Palembang Was Shown on Figure C6.4.1

Sector C The Study on Comprehensive Water Management of Final Report Musi River Basin in the Republic of Indonesia 6.4 Land Use and Land Use Plan in Palembang The current land use of Palembang was shown on Figure C6.4.1. PALEMBANG LAND USE MAP sa k o suk a r a me Ilir Barat I Ilir Timur I Ilir Tim ur II Seberang Ulu II Ilir Barat II LEGEND Administrative Boundary 1x Tidal Swamp Rice Field Agriculture Industy Seberang Ulu I Big Building Big Plantation Bushes Dry Agriculture Land Fresh Water Pond Graveyard N House Building Lak e Li vi ng Area Mi xed Land Non-agriculture Industry One Type Forest 2024Kilometers People Plantation Rain Rice Field Swamp / Marsh Temporary Opened Land Data Source : BAPPEDA 1:50,000 Land Use 2000 Tree and Bush Mixed Forest Un-identified Land Figure C6.4.1 Palembang Land Use Map C-46 JICA CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. NIKKEN Consultants, Inc. The Study on Comprehensive Water Management of Sector C Musi River Basin in the Republic of Indonesia Final Report In 1994, Palembang Municipality made the first spatial plan that the target years are from 1994 to 2004. 5 years late in 1998, this spatial plan was reviewed and evaluated by PT Cakra Graha through a contract project with Regional Development Bureau of Palembang Municipality (Contract No. 602/1664/BPP/1998). After the evaluation and analysis, a new spatial plan 1999 to 2009 was designed, however, the data used in the new spatial plan was the same as the one in the old plan 1994 to 2004. -

TARIQA of SAMMANIYAH PALEMBANG in 1900-1945: Struggle and Game Power of the Tariqa Sammaniyah Scholars in Maintaining the Existence of the Tariqa Sammaniyah

Proceedings of the 11th Annual International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Singapore, March 7-11, 2021 TARIQA OF SAMMANIYAH PALEMBANG IN 1900-1945: Struggle and Game Power of the Tariqa Sammaniyah Scholars In Maintaining the Existence of the Tariqa Sammaniyah Rudy Kurniawan Ph.D Candidate, Graduate Sociology in Faculty of Social and Politic Sciences, Universitas Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia, [email protected] Darsono Wisadirana, Sanggar Kanto, Siti Kholifah Postgraduate lecturer in Faculty of Social and Political sciences Universitas Brawijaya, Indonesia [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] M Chairul Basrun Umanailo Universitas Iqra Buru, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract This study aims to discuss the struggle of Sammaniyah scholars in maintaining the existence of Sammaniyah Tariqa at the beginning and in the middle of the 20th century. The struggle of these scholars began since the Dutch removed the Islamic-Malay poliltics from the neighborhood of Palembang Sultanate Palace in 1824. Although the Dutch had left Indonesia and there has been a change of power, apparently the struggle of Islamic scholars to maintain the exposition of the order is still done. The method of study used in this research is qualitative with genealogical approaches, where researchers analyze the relationship of power built by the Sammaniyah scholars in spreading Islam and maintaining the teachings of orders. The different treatment experienced by the Sammaniyah order has made the Islamic scholars make a strategy so that they can endure the middle of the regime. Establishing a power relationship with the power Regim is one of the steps of Sammaniyah scholars in maintaining the order through the process of Islamization. -

Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+), Transnational Conservation and Access to Land in Jambi, Indonesia

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Hein, Jonas Working Paper Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+), Transnational Conservation and Access to Land in Jambi, Indonesia EFForTS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2 Provided in Cooperation with: Collaborative Research Centre 990: Ecological and Socioeconomic Functions of Tropical Lowland Rainforest Transformation Systems (Sumatra, Indonesia), University of Goettingen Suggested Citation: Hein, Jonas (2013) : Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+), Transnational Conservation and Access to Land in Jambi, Indonesia, EFForTS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2, GOEDOC, Dokumenten- und Publikationsserver der Georg-August-Universität, Göttingen, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:gbv:7-webdoc-3904-5 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/117314 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Y3216 Lloyd's Agencies in Indonesia, Kota Kinabalu, Sandakan, Cayenne

Market Bulletin One Lime Street London EC3M 7HA FROM: Sonja Fink, Controller of Agencies Agency Department LOCATION: 86/Room 209 EXTENSION: 5735 DATE: 17 December 2003 REFERENCE: Y3216 SUBJECT: LLOYD’S AGENCIES IN INDONESIA, KOTA KINABALU, SANDAKAN, CAYENNE, PARAMARIBO, RECIFE, RIO DE JANEIRO, RIO GRANDE, SANTOS, HALMSTAD, GOTHENBURG, KARLSHAMN AND MALMO. SUBJECT AREA(S): None ATTACHMENTS: None ACTION POINTS: None DEADLINE: None LLOYD’S AGENCIES AT JAKARTA, MAKASSAR, MEDAN, PALEMBANG, SEMARANG AND SURABAYA. Please note that P.T.Superintending Company of Indonesia’s Lloyd’s Agency appointments at Makassar, Medan, Palembang, Semarang and Surabaya will terminate at the end of this year and that with effect from 1 January, 2004, PT Carsurin will be the appointed Lloyd’s Agents for Indonesia. Their full contact details are as follows: P.T.Carsurin Pekaka Building 7th Floor Jl. Angkasa Blok B-9 Kav 6 Kota Baru Bandar Kamayoran Jakarta 10720 Indonesia Contact : Captain Irawan Alwi or Captain Sunardi Setiaharja Telephone : +62 21 6540425 or 6540393 or 6540417 Facsimile : +62 21 6540418 Mobile : +62 811 103513 – Capt. Setiaharja Email : [email protected] Website : www.carsurin.com Lloyd’s is regulated by the Financial Services Authority 2 LLOYD’S AGENCIES AT KOTA KINABALU AND SANDAKAN. Harrisons Trading (Sabah) Sdn., Bhd., the Lloyd’s Agents at Kota Kinabalu and Sandakan have decided to amalgamate their existing two offices which will, with effect from 1st January 2004 be administered from Kota Kinabalu. As a result the Lloyd’s Agency at Sandakan is now a Sub-Agent of Kota Kinabalu, and its territory has been added to that of the Lloyd’s Agency at Kota Kinabalu, whose full contact details are as follows: Harrisons Trading (Sabah) Sdn., Bhd., 19 Jalan Haji Saman. -

Compilation of Manuals, Guidelines, and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (Ip) Portfolio Management

DRAFT FOR DISCUSSION COMPILATION OF MANUALS, GUIDELINES, AND DIRECTORIES IN THE AREA OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (IP) PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT CUSTOMIZED FOR THE ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS (ASEAN) MEMBER COUNTRIES TABLE OF CONTENTS page 1. Preface…………………………………………………………………. 4 2. Mission Report of Mr. Lee Yuke Chin, Regional Consultant………… 5 3. Overview of ASEAN Companies interviewed in the Study……...…… 22 4. ASEAN COUNTRIES 4. 1. Brunei Darussalam Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 39 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 53 4. 2. Cambodia Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 66 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 85 4. 3. Indonesia Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 96 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 113 4. 4. Lao PDR Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 127 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 144 4. 5. Malaysia Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 156 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 191 4. 6. Myanmar Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 213 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 232 4. 7. Philippines Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 248 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 267 4. 8. Singapore Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. -

Waqf Administration in Historical Perspective: Evidence from Indonesia

November-December 2019 ISSN: 0193-4120 Page No. 5338 - 5353 Waqf Administration in Historical Perspective: Evidence from Indonesia Ulya Kencana Universitas Islam Negeri Raden Fatah Palembang, Indonesia Miftachul Huda Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, Malaysia Andino Maseleno Universiti Tenaga Nasional, Malaysia Article Info Abstract: Volume 81 Page Number: 5338 - 5353 The practice of waqf law in Islam has grown and developed in society. Publication Issue: Endowments exist because people do it. In Malay society in Palembang, waqf has November-December 2019 legally become a source. The purpose of waqf legally is to provide benefits (benefits) for the community in a sustainable manner. The findings in the field show that the practice of waqf has existed and exists in the life of the Palembang Darussalam Malay community. The practice of written waqf was done at that time. Endowments since the end of the 18th century AD and / or the beginning of the 19th century AD, have been carried out by charismatic scholars, who were rescued by the people of Palembang, namely Masagus Haji Abdul Hamid bin Mahmud bin Kanang, known as Kiai Marogan. The main data of research about waqf Masagus Haji Abdul Hamid bin Mahmud is not yet known to the general public, especially productive waqf in Mecca (waqf imarah / hotel). In contrast to the reality on the ground today in Palembang, the practice of written legal waqf does not have a written legal waqf agreement. Research conducted descriptively to explain the history of Islam's first entry into Palembang was related to the practice of waqf in Palembang at that time as part of the tradition of Malay Civilization in the Sultanate of Palembang Darussalam. -

The West Papua Dilemma Leslie B

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2010 The West Papua dilemma Leslie B. Rollings University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Rollings, Leslie B., The West Papua dilemma, Master of Arts thesis, University of Wollongong. School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2010. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3276 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. School of History and Politics University of Wollongong THE WEST PAPUA DILEMMA Leslie B. Rollings This Thesis is presented for Degree of Master of Arts - Research University of Wollongong December 2010 For Adam who provided the inspiration. TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION................................................................................................................................ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. ii ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... iii Figure 1. Map of West Papua......................................................................................................v SUMMARY OF ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................1 -

ND Revises Ticket Exchange UN Conference on Women Will Be Using the Exchange These Changes Come As a Re New System Ticket, Scholl Reported

----------------- -~~~- Monday, October 9, 1995• Vol. XXVII No.36 TI-lE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING NOTRE DAME AND SAINT MARYS Retiring colonel reflects on 30 years of Air Force service BY PEGGY LENCZEWSKI Saint Mary's News Editor After years of steadfast service to his country, •• ·.:o-. '•"" including time as a prisoner of war in Vietnam, Thomas Moe has decided to return to civilian life. Colonel Thomas Moe, Commander, Air Force HOTC, retired on Saturday, Oct. 5, ending a thirty year career. For the past three years, Moe A ~ ""': .. was responsible for recruiting lf'P and training eadel<; to be com- < · : ml.,ionod in the United States ~: Air Force. But his dossier . .·. ' could fill volumes. · . ~:~ Dancin' up a Moe's decorated career in- ·· . eludes several prestigious ,>........_ storm! awards, including the Silver Colon~l Moe Star with oak leaf cluster, which is the third highest Helping to celebrate Multicultural award for valor given out by the Air Force. He has Week, Potowatomi Indians performed also been awarded the Defense Superior Service at the Fieldhouse Mall last Thursday. Medal, which is the second highest award issued for non-combat behavior. Notre Dame and Saint Marys' students Moe says that the highlights of his eareer. were asked to participate In a friend irlcludcd "gettting the best jobs. I was able to fly ship dance as part of the occasion. lighter planes. I had a tour of duty as an attache in the U.S. Embassy in Switzerland, which was The performance attracted a large good for my family. I was also able to serve as crowd due to the loud, rhythmic head of HOTC at Notre Dame." sounds of the drums which echoed For his time spent as a prisoner of war in the richness of Native American cul Vietnam. -

Asian Agri's Traceability System – One to One Partnership Commitment

ASIAN AGRI’S TRACEBILITY SYSTEM: ONE TO ONE PARTNERSHIP COMMITMENT By: Bernard Alexander Riedo Director of Sustainability and Stakeholder Relations ABOUT ASIAN AGRI NORTH SUMATRA RIAU ESTABLISHED IN 1979 JAMBI Asian Agri is a leading national palm oil company that put partnership with smallholders as its Owned Estates 100,000 ha main business model Plasma 60,000 ha Smallholders’ estates Independent 36,000 ha Smallholders’ estates ABOUT ASIAN AGRI RIAU N. SUMATRA 39k Ha (Owned) 35k Ha (Plasma) 43k Ha (Owned) 9 CPO Mills 8 CPO Mills 4 KCPs 2 KCPs 3 Biogas Plants 2 Biogas Plants R&D Center R&D Center Training Center JAMBI 18k Ha (Owned) 23k Ha (Plasma) 4 CPO Mills 3 KCPs One of the largest RSPO, ISPO & ISCC certified oil producers in the world. 2 Biogas Plants The 1st company with RSPO & ISPO certified independent smallholders MILESTONE 1979 1983 1987 1989 1991 Acquired 8,000 1st Palm Oil Mill Pioneered Plasma Established Successfully Ha land bank in in Gunung Melayu schemes in Riau state of the art developed and north Sumatra st & Jambi R&D centre hand over 1 Plasma estate 2006 2005 2002 1996 Implement ZERO BURN Set up seed DxP Progeny during land Asian Agri became Established producing testing to produce member of RSPO Planters School preparation facilities - OPRS of Excellence high yielding seeds 1994 2012 2013 2014 2015 – 2017 7 units of Biogas Set up Tissue & 13 planned Achieve beyond Biggest ISCC & Achieve 50% yield Culture lab to RSPO certified 1 Mn MT CPO Vol improvement in Kick Start Plasma clone oil palms smallholders in replanting -

Interim Sesa Document Ministry of Environment

INTERIM SESA DOCUMENT MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND FORESTRY JAMBI PROVINCE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA October 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .....................................................................................I LIST OF TABLES.............................................................................................III LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................... IV LIST OF APPENDICES ................................................................................... V LIST OF ACRONYMS ..................................................................................... VI 1.0 INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................1 1.1 BACKGROUND............................................................................................. 1 1.2 OBJECTIVE .................................................................................................. 4 1.3 SCOPE OF THE SESA.................................................................................. 5 2.0 APPROACH ............................................................................................6 2.1 DATA COLLECTION ..................................................................................... 6 2.2 SCREENING AND SCOPING FOR THE SESA............................................. 7 2.2.1 Formulation of Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation ..................................................................................... 7 2.2.2