Open PDF 249KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Edward Leigh Onorificenza Commendatore Osi My Lords

Sir Edward Leigh Onorificenza Commendatore Osi My Lords, Ladies and Gentlemen, a very good evening and welcome to the Italian Embassy. Thank you all for coming here this evening to celebrate the presentation of the Commendatore della Stella d’Italia award, bestowed upon our friend Sir Edward Leigh by the Italian President. First I would like to start saying a few words on this prestigious award. The different ranks of the order of the Stella d’Italia are bestowed upon Italians living abroad and foreign nationals, in recognition of their special merits in fostering friendly relations and cooperation between Italy and their country of residence and the promotion of ties with Italy. Since the start of the order only 4675 Commendatori of the Italian Star have been awarded. 1 A small army of friends of Italy from the four corners of the globe. I am glad that Sir Edward’s name has now been added to this prestigious list of distinguished individuals. It is my personal honor to welcome Sir Edward Leigh to the Embassy today. Sir Edward has been member of the House of Commons since 1983 and recently won his ninth consecutive parliamentary election. As well as being a well renowned politician, Sir Edward is also a qualified barrister, he practiced in arbitration and criminal law for Goldsmiths Chambers, and has served as an Independent Financial Advisor to the Treasury. Since 2011, he has also been elected as Chairman of the Public Accounts Commission, the body which audits the National Audit Office, responsible for saving the taxpayer over £4 billion. -

![The National Audit Office, the Public Accounts Committee and the Risk Landscape in UK Public Policy Discussion Paper [Or Working Paper, Etc.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3538/the-national-audit-office-the-public-accounts-committee-and-the-risk-landscape-in-uk-public-policy-discussion-paper-or-working-paper-etc-93538.webp)

The National Audit Office, the Public Accounts Committee and the Risk Landscape in UK Public Policy Discussion Paper [Or Working Paper, Etc.]

Patrick Dunleavy, Christopher Gilson, Simon Bastow and Jane Tinkler The National Audit Office, the Public Accounts Committee and the risk landscape in UK Public Policy Discussion paper [or working paper, etc.] Original citation: Dunleavy, Patrick, Christopher Gilson, Simon Bastow and Jane Tinkler (2009): The National Audit Office, the Public Accounts Committee and the risk landscape in UK public policy. URN 09/1423. The Risk and Regulation Advisory Council, London, UK. This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/25785/ Originally available from LSE Public Policy Group Available in LSE Research Online: November 2009 © 2009 the authors LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. The National Audit Office, the Public Accounts Committee and the Risk Landscape in UK Public Policy Patrick Dunleavy, Christopher Gilson, Simon Bastow and Jane Tinkler October 2009 The Risk and Regulation Advisory Council This report was produced in July 2009 for the Risk and Regulation Advisory Council. The Risk and Regulation Advisory Council is an independent advisory group which aims to improve the understanding of public risk and how to respond to it. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Friday Volume 607 11 March 2016 No. 131 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Friday 11 March 2016 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2016 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 545 11 MARCH 2016 Foreign National Offenders 546 (Exclusion from the UK) Bill There are 10,442 foreign national prisoners in our House of Commons prisoners out of a total of 85,886—12% of the prison population. You will perhaps be surprised to learn, Friday 11 March 2016 Mr Speaker, that those 10,442 come not just from one, two, three, four, half a dozen or a dozen countries, but from some 160 countries from around the world. Indeed, The House met at half-past Nine o’clock 80% of the world’s nations are represented in our prisons. We are truly an internationally and culturally diverse PRAYERS nation, even in our imprisoned population. Very worryingly indeed, something like a third of them have been convicted of violent and sexual offences; a fifth have been convicted [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] of drugs offences; and others have been convicted of burglary, robbery, fraud and other serious crimes. Mr David Nuttall (Bury North) (Con): I beg to move, That the House sit in private. It is a good thing that the crimes have been detected, Question put forthwith (Standing Order No. 163), and the evidence has been gathered and these people are negatived. being punished for their offences. It is, however, completely wrong that the cost of that imprisonment should fall on British taxpayers, because these individuals—every single Foreign National Offenders (Exclusion last one of them—should be repatriated to secure detention from the UK) Bill in their country of origin, so that taxpayers from their Second Reading own countries can pay the bill for their incarceration and punishment. -

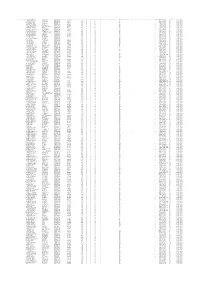

Voter Registration Number Name

VOTER REGISTRATION NUMBER NAME: LAST, FIRST, MIDDLE RESIDENTIAL ADDRESS: FULL STREET RESIDENTIAL ADDRESS: CITY/STATE/ZIP TELEPHONE: FULL NUMBER AGE AT YEAR END PARTY CODE RACE CODE GENDER CODE ETHNICITY CODE STATUS CODE JURISDICTION: MUNICIPAL DISTRICT CODE JURISDICTION: MUNICIPALITY CODE JURISDICTION: SANITATION DISTRICT CODE JURISDICTION: PRECINCT CODE REGISTRATION DATE VOTED METHOD VOTED PARTY CODE ELECTION NAME 141580 ACKISS, FRANCIS PAIGE 2 MULBERRY LN # A NEW BERN, NC 28562 252-671-5911 67 UNA W M NL A RIVE 5 2/25/2015 IN-PERSON UNA 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 140387 ADAMS, CHARLES RAYMOND 4100 HOLLY RIDGE RD NEW BERN, NC 28562 910-232-6063 74 DEM W M NL A TREN 3 10/10/2014 IN-PERSON DEM 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 20141 ADAMS, KAY RUSSELL 3605 BARONS WAY NEW BERN, NC 28562 252-633-2732 66 REP W F NL A TREN 3 5/24/1976 IN-PERSON REP 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 157173 ADAMS, LAUREN PAIGE 204 A ST BRIDGETON, NC 28519 252-474-9712 18 DEM W F NL A BRID FC 11 4/21/2017 IN-PERSON DEM 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 20146 ADAMS, LYNN EDWARD JR 3605 BARONS WAY NEW BERN, NC 28562 252-633-2732 69 REP W M NL A TREN 3 3/31/1970 IN-PERSON REP 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 66335 ADAMS, TRACY WHITFORD 204 A ST BRIDGETON, NC 28519 252-229-9712 47 REP W F NL A BRID FC 11 4/2/1998 IN-PERSON REP 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 49660 ADELSPERGER, ROBERT DEWEY 101 CHADWICK AVE HAVELOCK, NC 28532 252-447-0979 67 REP W M NL A HAVE 2 2/2/1994 IN-PERSON REP 11/07/2017 MUNICIPAL 71341 AGNEW, LYNNE ELIZABETH 31 EASTERN SHORE TOWNHOUSES BRIDGETON, NC 28519 252-638-8302 66 REP W F NL A BRID FC 11 7/27/1999 IN-PERSON -

Public Accounts Commission Oral Evidence: NAO Strategy 2018-19 to 2020-21

Public Accounts Commission Oral evidence: NAO Strategy 2018-19 to 2020-21 Tuesday 12 December 2017 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 12 December 2017. Watch the meeting Members present: Sir Edward Leigh (Chair); Mr Richard Bacon; Jack Brereton; Clive Efford; Julian Knight; Andrea Leadsom. Richard Brown, Treasury Officer of Accounts, and James Fraser, Senior Policy Adviser, Accountability and Governance, HM Treasury, were in attendance. Questions 1-70 Witnesses I: Sir Amyas Morse, KCB, Comptroller and Auditor General, National Audit Office, Lord Bichard, Chair, National Audit Office, and Daniel Lambauer, Executive Leader, Strategy and Operations, National Audit Office. Written evidence from witnesses: – [Add names of witnesses and hyperlink to submissions] Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Sir Amyas Morse KCB, Lord Bichard and Daniel Lambauer. Q1 Chair: Good morning, Lord Bichard and Sir Amyas. How nice to see you. Welcome to the Public Accounts Commission’s first meeting of this new Parliament. This morning we are discussing your strategy. I will lead the questioning. You are seeking funding for a contingency of 2% a year on top of your pay bill. That is on top of the 1% already allowed for. Obviously, we were quite concerned about this, and we want some reassurance from you, because it is unusual in the public sector. We are interested to know what sort of evidence would need to be presented to your board before you would seek to draw on this extra money. Sir Amyas Morse: The evidence that we would have is advice from our pay consultants, which will not be available until January. -

General Election 2015 Results

General Election 2015 Results. The UK General Election was fought across all 46 Parliamentary Constituencies in the East Midlands on 7 May 2015. Previously the Conservatives held 30 of these seats, and Labour 16. Following the change of seats in Corby and Derby North the Conservatives now hold 32 seats and Labour 14. The full list of the regional Prospective Parliamentary Candidates (PPCs) is shown below with the elected MP is shown in italics; Amber Valley - Conservative Hold: Stuart Bent (UKIP); John Devine (G); Kevin Gillott (L); Nigel Mills (C); Kate Smith (LD) Ashfield - Labour Hold: Simon Ashcroft (UKIP); Mike Buchanan (JMB); Gloria De Piero (L); Helen Harrison (C); Philip Smith (LD) Bassetlaw - Labour Hold: Sarah Downs (C); Leon Duveen (LD); John Mann (L); David Scott (UKIP); Kris Wragg (G) Bolsover - Labour Hold: Peter Bedford (C); Ray Calladine (UKIP); David Lomax (LD); Dennis Skinner (L) Boston & Skegness - Conservative Hold: Robin Hunter-Clarke (UKIP); Peter Johnson (I); Paul Kenny (L); Lyn Luxton (TPP); Chris Pain (AIP); Victoria Percival (G); Matt Warman (C); David Watts (LD); Robert West (BNP). Sitting MP Mark Simmonds did not standing for re-election Bosworth - Conservative Hold: Chris Kealey (L); Michael Mullaney (LD); David Sprason (UKIP); David Tredinnick (C) Broxtowe - Conservative Hold: Ray Barry (JMB); Frank Dunne (UKIP); Stan Heptinstall (LD); David Kirwan (G); Nick Palmer (L); Anna Soubry (C) Charnwood - Conservative Hold: Edward Argar (C); Cathy Duffy (BNP); Sean Kelly-Walsh (L); Simon Sansome (LD); Lynton Yates (UKIP). Sitting MP Stephen Dorrell did not standing for re- election Chesterfield - Labour Hold: Julia Cambridge (LD); Matt Genn (G); Tommy Holgate (PP); Toby Perkins (L); Mark Vivis (C); Matt Whale (TUSC); Stuart Yeowart (UKIP). -

Rt. Hon. Sir Edward Leigh MP

Rt. Hon. Sir Edward Leigh MP Arts Council England 21 Bloomsbury Street Bloomsbury London WC1B 3HF Monday, 10th August 2020 To whom it may concern, Announced in July, the Culture Recovery Fund will see Britain’s globally renowned arts, culture and heritage industries receive a total of £1.57 billion to help them weather coronavirus and come back stronger, protecting jobs and safeguarding a much cherished sector for future generations. Following dialogue between Sir Edward Leigh MP and the team at Trinity Arts Centre, an application is being made for funding to provide financial support over the next financial year, enabling it to bounce back and recover after having to close its doors due to coronavirus. Trinity Arts Centre is central to the cultural life of Gainsborough and has been cherished and enjoyed by our community for many years. Significant progress had been made on improving the cultural offer of the centre and deliver high quality, accessible arts in one of the most deprived neighbourhoods in the UK. I fully support the bid to provide financial stability, recover lost box office income due to the pandemic, support the livelihoods of the centre’s staff, support delivery of a new programme for 2021 and build capacity and resilience with essential equipment which in the short term assists with social distancing requirements. I particularly welcome the ambition for Trinity Arts Centre to be ‘net to landfill’. I know this year has been difficult for everyone due to the coronavirus, but we must not let fantastic venues like this close and be lost to future generations, which is why I am writing to your organisation asking that you look favourably on their application for support. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

Missouri State Archives Finding Aid 5.20

Missouri State Archives Finding Aid 5.20 OFFICE OF SECRETARY OF STATE COMMISSIONS PARDONS, 1836- Abstract: Pardons (1836-2018), restorations of citizenship, and commutations for Missouri convicts. Extent: 66 cubic ft. (165 legal-size Hollinger boxes) Physical Description: Paper Location: MSA Stacks ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION Alternative Formats: Microfilm (S95-S123) of the Pardon Papers, 1837-1909, was made before additions, interfiles, and merging of the series. Most of the unmicrofilmed material will be found from 1854-1876 (pardon certificates and presidential pardons from an unprocessed box) and 1892-1909 (formerly restorations of citizenship). Also, stray records found in the Senior Reference Archivist’s office from 1836-1920 in Box 164 and interfiles (bulk 1860) from 2 Hollinger boxes found in the stacks, a portion of which are in Box 164. Access Restrictions: Applications or petitions listing the social security numbers of living people are confidential and must be provided to patrons in an alternative format. At the discretion of the Senior Reference Archivist, some records from the Board of Probation and Parole may be restricted per RSMo 549.500. Publication Restrictions: Copyright is in the public domain. Preferred Citation: [Name], [Date]; Pardons, 1836- ; Commissions; Office of Secretary of State, Record Group 5; Missouri State Archives, Jefferson City. Acquisition Information: Agency transfer. PARDONS Processing Information: Processing done by various staff members and completed by Mary Kay Coker on October 30, 2007. Combined the series Pardon Papers and Restorations of Citizenship because the latter, especially in later years, contained a large proportion of pardons. The two series were split at 1910 but a later addition overlapped from 1892 to 1909 and these records were left in their respective boxes but listed chronologically in the finding aid. -

John Ben Shepperd, Jr. Memorial Library Catalog

John Ben Shepperd, Jr. Memorial Library Catalog Author Other Authors Title Call Letter Call number Volume Closed shelf Notes Donated By In Memory Of (unkown) (unknown) history of the presidents for children E 176.1 .Un4 Closed shelf 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) Ruth Goree and Jane Brown 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) Anonymous 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) Bobbie Meadows Beulah Hodges 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) 1981 Presidential Inaugural Committee (U.S.) A Great New Beginning: the 1981 Inaugural Story E 877.2 .G73 A Citizen of Western New York Bancroft, George Memoirs of General Andrew Jackson, Seventh President of the United States E 382 .M53 Closed shelf John Ben Shepperd A.P.F., Inc. A Catalogue of Frames, Fifteenth Century to Present N 8550 .A2 (1973) A.P.F. Inc. Aaron, Ira E. Carter, Sylvia Take a Bow PZ 8.9 .A135 Abbott, David W. Political Parties: Leadership, Organization, Linkage JK 2265 .A6 Abbott, John S.C. Conwell, Russell H. Lives of the Presidents of the United States of America E 176.1 .A249 Closed shelf Ector County Library Abbott, John S.C. -

Open PDF 118KB

House of Commons The Public Accounts Commission Twenty-sixth Report: Work of the Commission in 2020 Presented to the House of Commons pursuant to section 2(3) of the National Audit Act 1983 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 12 July 2021 HC 510 Published on 12 July 2021 by authority of the House of Commons The Public Accounts Commission The Public Accounts Commission is defined by the National Audit Act 1983 and the Budget Responsibility and National Audit Act 2011. The Commission’s principal duties under the Acts are to review the National Audit Office (NAO) Estimate and lay it before the House of Commons, to appoint the accounting officer for the NAO, to appoint an auditor for the NAO, to appoint non-executive members of the NAO board (other than the chairman), and to report from time to time. Current membership Mr Richard Bacon MP (Conservative, South Norfolk) (Chair) Jack Brereton MP (Conservative, Stoke-on-Trent South) Nicholas Brown MP (Labour, Newcastle upon Tyne East) Anthony Browne MP (Conservative, South Cambridgeshire) Clive Efford MP (Labour, Eltham) Peter Grant MP (Scottish National Party, Glenrothes) Meg Hillier MP (Labour (Co-op), Hackney South and Shoreditch) (ex-officio as Chair of the Public Accounts Committee) Sir Edward Leigh MP (Conservative, Gainsborough) Jacob Rees-Mogg MP (Conservative, North East Somerset) Publications The Reports and evidence of the Commission are published by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee can be found on the publications page of the Committee website. Committee staff The current staff of the Commission are Kevin Maddison (Secretary to the Commission) and Arvind Gunnoo (Committee Operations Officer).