Containing Ebola – a Success Story from an “Unexpected” Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigeria MLA Replies to the Pandemic Response Questionnaire

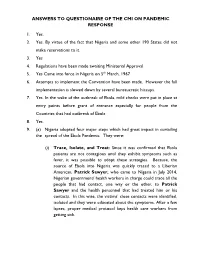

ANSWERS TO QUESTIONAIRE OF THE CMI ON PANDEMIC RESPONSE 1. Yes. 2. Yes. By virtue of the fact that Nigeria and some other 190 States did not make reservations to it. 3. Yes 4. Regulations have been made awaiting Ministerial Approval 5. Yes Came into force in Nigeria on 5th March, 1967 6. Attempts to implement the Convention have been made. However the full implementation is slowed down by several bureaucratic hiccups. 7. Yes. In the wake of the outbreak of Ebola, mild checks were put in place at entry points before grant of entrance especially for people from the Countries that had outbreak of Ebola 8. Yes. 9. (a) Nigeria adopted four major steps which had great impact in curtailing the spread of the Ebola Pandemic. They were: (i) Trace, Isolate, and Treat: Since it was confirmed that Ebola patients are not contagious until they exhibit symptoms such as fever, it was possible to adopt these strategies. Because, the source of Ebola into Nigeria was quickly traced to a Liberian American, Patrick Sawyer, who came to Nigeria in July 2014, Nigerian government/ health workers in charge could trace all the people that had contact, one way or the other, to Patrick Sawyer and the health personnel that had treated him or his contacts. In this wise, the victims’ close contacts were identified, isolated and they were educated about the symptoms. After a few lapses, proper medical protocol kept health care workers from getting sick. (ii) Early Detection before many people could be exposed: It is generally believed that anyone with Ebola, typically, will infect about two more people, unless something is done to intervene. -

Impact of Ebola Virus Disease on School Administration in Nigeria

American International Journal of Contemporary Research Vol. 5, No. 3; June 2015 Impact of Ebola Virus Disease on School Administration in Nigeria Oladunjoye Patrick, PhD Major, Nanighe Baldwin, PhD Niger Delta University Educational Foundations Department Wilberforce Island Bayelsa State Nigeria Abstract This study is focused on the impact of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) on school administration in Nigeria. Two hypothesis were formulated to guide the study. A questionnaire titled Ebola Virus Disease and school administration (EVDSA) was used to collect data. The instrument was administered to one hundred and seventeen (117) teachers and eighty three (83) school administrators randomly selected from the three (3) regions in the federal republic of Nigeria. This instrument was however validated by experts and tested for reliability using the test re-test method and data analyzed using the Pearson Product Moment Correlation Coefficient. The result shows that there is a significant difference between teachers and school heads in urban and rural areas on the outbreak of the EVD. However, there is no significant difference in the perception of teachers and school heads in both urban and rural areas on the effect of EVD on attendance and hygiene in schools. Based on these findings, recommendations were made which include a better information system to the rural areas and the sustenance of the present hygiene practices in schools by school administrators. Introduction The school and the society are knitted together in such a way that whatever affects the society will invariably affect the school. When there are social unrest in the society, the school attendance may be affected. -

Order Paper 5 November, 2019

FOURTH REPUBLIC 9TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FIRST SESSION NO. 54 237 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Tuesday 5 November, 2019 1. Prayers 2. National Pledge 3. Approval of the Votes and Proceedings 4. Oaths 5. Message from the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 6. Message from the Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 7. Messages from Other Parliament(s) (if any) 8. Other Announcements (if any) 9. Petitions (if any) 10. Matter(s) of Urgent Public Importance 11. Personal Explanation ______________________________________________________________ PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. Federal College of Agriculture, Katcha, Niger State (Establishment) Bill, 2019 (HB.403) (Hon. Saidu Musa Abdullahi) – First Reading. 2. Public Service Efficiency Bill, 2019 (HB.404) (Hon. Saidu Musa Abdullahi) – First Reading. 3. Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (Alteration) Bill, 2019 (HB.405) (Hon. Saidu Musa Abdullahi) – First Reading. 4. Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (Alteration) Bill, 2019 ((HB.406) (Hon. Dachung Musa Bagos) – First Reading. 5. National Rice Development Council Bill, 2019 (HB.407) (Hon. Saidu Musa Abdullahi) – First Reading. 238 Tuesday 5 November, 2019 No. 54 6. Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (Alteration) Bill, 2019 (HB.408) (Hon. Dachung Musa Bagos) – First Reading. 7. Counselling Practitioners Council of Nigeria (Establishment) Bill, 2019 (HB.409) (Hon. Muhammad Ali Wudil) – First Reading. 8. Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (Alteration) Bill, 2019 (HB.410) (Hon. Dachung Musa Bagos) – First Reading. 9. Federal University of Medicine and Health Services, Bida, Niger State (Establishment) Bill, 2019 (HB.411) (Hon. -

What We Can Learn from and About Africa in the Corona Crisis The

Pockets of effectiveness What we can learn from and about Africa in the corona crisis by Michael Roll, German Development Institute / D eutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE) The Current Column of 2 April 2020 Pockets of effectiveness What we can learn from and about Africa in the corona crisis Is Africa defenceless in the face of the corona pandemic? This to a treatment centre. In total, 20 people became infected in would appear to be self-evident, as even health care systems Nigeria in 2014 and eight of them died. The WHO lauded the far better equipped than those of many African countries are successful contact-tracing work under very difficult condi- currently on the verge of collapse. Nonetheless, such a con- tions as a piece of “world-class epidemiological detective clusion is premature. In part, some African countries are work”. even better prepared for pandemics than Europe and the What does this mean for corona in Nigeria and in Africa? As a United States. Nigeria’s success in fighting its 2014 Ebola result of their experience with infectious diseases, many Afri- outbreak illustrates why that is the case and what lessons can countries have established structures for fighting epidem- wealthier countries and the development cooperation com- ics in recent years. These measures and the continent’s head munity can learn from it. start over other world regions are beneficial for tackling the Learning from experience corona pandemic. However, this will only help at an early stage when the chains of infection can still be broken by iden- Like other African countries, Nigeria has experience in deal- tifying and isolating infected individuals. -

BY the TIME YOU READ THIS, WE'll ALL BE DEAD: the Failures of History and Institutions Regarding the 2013-2015 West African Eb

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2015 BY THE TIME YOU READ THIS, WE’LL ALL BE DEAD: The failures of history and institutions regarding the 2013-2015 West African Ebola Pandemic. George Denkey Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, International Public Health Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Denkey, George, "BY THE TIME YOU READ THIS, WE’LL ALL BE DEAD: The failures of history and institutions regarding the 2013-2015 West African Ebola Pandemic.". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2015. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/517 BY THE TIME YOU READ THIS, WE’LL ALL BE DEAD: The failures of history and institutions regarding the 2013-2015 West African Ebola Pandemic. By Georges Kankou Denkey A Thesis Submitted to the Department Of Urban Studies of Trinity College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts Degree 1 Table Of Contents For Ameyo ………………………………………………..………………………........ 3 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Acknowledgments ………………………………………………………………………. 5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………… 6 Ebola: A Background …………………………………………………………………… 20 The Past is a foreign country: Historical variables behind the spread ……………… 39 Ebola: The Detailed Trajectory ………………………………………………………… 61 Why it spread: Cultural -

Review Article Ebola Virus Disease

International Journal of Nursing Research (IJNR) International Peer Reviewed Journal Review article Ebola virus disease: Comprehensive review Archana R. Dhanawade Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University College of Nursing,, Sangli, Maharashtra, India Abstract Ebola is a Filoviridae virus with characteristic filamentous structure of a thread virus. It became a global threat when its outbreak has affected lives of thousands of people including doctors, nursing staff, healthcare workers. The virus spreads via direct contact with blood or body fluids from an infected person in an uncontrolled manner with limited treatment options. The Ebola virus disease is a very serious health problem causing major deaths within a short period. As there are no specific treatment or vaccines available, prevention is the only option to control the spread of disease. So, the health team members, the staff nurses who are more prone to this disease should have adequate knowledge about the disease and its prevention to handle the situation. Keywords: Ebola Virus Disease, nursing, health problem *Corresponding author: Archana R. Dhanawade, Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University College of Nursing,, Sangli, Maharashtra, India, India. Email: [email protected] 1. Introduction of Ebola virus disease months later the second outbreak of Ebola virus emerged from Zaire with highest mortality rate The recent outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) infecting 318 people. In spite of tremendous has revealed many weaknesses in the public efforts of experienced and dedicated researchers, healthcare system in controlling the spread of Ebola’s natural reservoir was not identified. The disease. In addition, the outbreak has affected third outbreak of Ebola was identified in 1989 lives of thousands of people including doctors, when infected monkeys were imported into nursing staff and healthcare workers [1]. -

Learning from Ebola: How Drug-Development Policy Could Help Stop Outbreaks of Infectious Diseases*

Learning from Ebola: How Drug-Development Policy Could Help Stop Outbreaks of Infectious Diseases* William W. Fisher III** and Katrina Geddes*** Version 3.2; October 14, 2015 Between 2013 and 2015, an outbreak of Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever killed more than 11,000 people and devastated three countries in western Africa. Preventing or limiting similar outbreaks in the future will require public-health initiatives of many sorts. This essay examines one such initiative that has thus far received little attention: modification of the policies used by governments and nongovernmental organizations to shape the development and distribution of pharmaceutical products aimed at infectious diseases. Part I of the paper summarizes the epidemiology of Ebola and the history of the recent outbreak. Part II considers the potential role of vaccines and medicines in combating Ebola and why we have thus far failed to develop them. Part III describes the various research projects provoked by the recent outbreak. Part IV considers several ways in which our drug development policies might be altered – either fundamentally or incrementally – that could strengthen the portfolio of ongoing research projects and reduce the incidence or severity of similar outbreaks in the future. I. Background The Ebola virus (EBOV) is an aggressive pathogen that causes a hemorrhagic shock syndrome in infected humans. Symptoms of that syndrome include fever, headache, fatigue, vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, rash, coagulation abnormalities, and a range of hematological irregularities such as lymphopenia (abnormally low levels of lymphocytes) and neutrophilia (abnormally high levels of neutrophil granulocytes).1 These symptoms typically first appear 8 to 10 days after exposure to the virus.2 If untreated, they usually result in death * An early draft of this paper was prepared for a workshop, hosted by Global Access in Action, held at Harvard University on July 10, 2015. -

Resident's Roles in the Optimization of the Preparedness Protocols For

1 Article 2 Resident’s roles in the optimization of the preparedness 3 protocols for Ebola pandemic in urban environment 4 Analysis of Residents’ preparedness protocols during Ebola 5 pandemic in urban environment 6 7 Emmanuel O. Amoo 1,*, Gbolahan A. Oni 1, Aize Obayan 2,3, Amos Alao 3, Olujide Adekeye 3, Gbemisola Samuel 1, 8 Samuel A. Oyegbile 4 and Evaristus Adesina 9 1 Demography and Social Statistics, College of Business and Social Sciences, Covenant University, Ota, Ogun 10 State, Nigeria. 11 2 African Leadership Development Centre, Covenant University, Canaanland, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria. 12 3 Department of Psychology, College of Leadership and Development Studies, Covenant University, Canaan- 13 land, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria. 14 4 Health Peak Medical Centre, 21 Ibido Street, Agege, Lagos State, Nigeria. 15 * Correspondence: [email protected] 16 Abstract: Background: The study provided empirical analysis of the Citation: Amoo, E.O.; Oni, G.; 17 change in hygiene behavioural practices among community in Obayan, A.; Alao, A.; Adekeye, O.; 18 Ogun and Lagos State with respect to Ebola outbreak in Nigeria. The study Samuel, G.; Oyegbile, S.A.; Adesina, 19 assessed men’s role in the preparedness against emerging pandemic of Ebola Virus Disease in Ogun E. Resident’s roles in the optimiza- tion of the preparedness protocols 20 State, Nigeria. It examined the changes in men’s hygiene practices as response to the news of the for Ebola pandemic in urban envi- 21 outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD). Methods: The data were extracted from a 2015 Cross-Sec- ronment. Sustainability 2021, 13, x. -

Globalisation and Ebola Disease: Implications for Business Activities in Nigeria

Vol. 11(3), pp. 47-56, 14 February, 2017 DOI: 10.5897/AJBM2016.8133 Article Number: 45213C962735 ISSN 1993-8233 African Journal of Business Management Copyright © 2017 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJBM Full Length Research Paper Globalisation and Ebola disease: Implications for business activities in Nigeria Adebanji Ayeni1*, Oluwole Oladele Iyiola2, Ogunnaike Olaleke Oluseye2 and Ibidunni Ayodotun Stephen2 1Elizade University, Ilara-Mokin, Ondo State, Nigeria. 2Department of Business Administration, Covenant University, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria. Received 28 July, 2016; Accepted 19 January,2017 With the Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa, it is expected that whatever the transmitting cause and spread of the virus, it has affected the economic, political and socio- economy activities with an immense strain on the health sector. The scope of this study is the most populous nation in Africa, Nigeria. The quantitative method adopted provided results from questionnaires, which were analysed and resulted in providing the underlined significant role of globalisation in the development of Nigeria business activities and socio-psychological impact of the epidemic virus on globalisation. This is in line with the cross-border spread of the disease in generating bi-lateral strain amongst the affected countries, thus been envisioned from the spread of Ebola Virus. In the course of the paper, epidemics of such degrees in the past were reviewed by looking at how they surfaced, resurfaced and combated. The paper stresses on the role of globalisation in spreading, maintaining and eliminating the virus and its socio-economic implications in Nigeria and her related activities. -

Confirmed Nigeria Ebola Cases Rises to 11 14 August 2014

Confirmed Nigeria Ebola cases rises to 11 14 August 2014 The number of confirmed Ebola cases in Nigeria The worst-ever outbreak of Ebola has killed more has risen by one to 11, Health Minister Onyebuchi than 1,000 people since the start of the year in Chukwu said on Thursday. Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. Nigeria last month became the fourth west African country The figure includes three deaths and eight people affected. who are being treated at a special isolation unit set up in Lagos, a megacity of more than 20 million © 2014 AFP people, the minister told reporters. Nigeria has not recorded a case outside Lagos but there were fears that a nurse who was infected in the city may have carried the virus to the key eastern city of Enugu. The nurse was among those who treated Liberian government employee Patrick Sawyer, who brought Ebola to Lagos on July 20. He died in hospital on July 25. After contracting the virus, the nurse travelled to Enugu, where she began showing symptoms before being transported back to Lagos for treatment. Officials on Wednesday said 21 people in Enugu who had contact with the nurse were being monitored. But Chukwu said Thursday that 15 of those people had been cleared, with only six in Enugu still being watched. The development is a positive one for health workers in Africa's most populous country, as a spread of the outbreak beyond Lagos would put significant strain on Nigeria's weak healthcare system. The number of people under surveillance for possible infection in Lagos was reduced from 177 to 169 overnight, Chukwu added. -

Antiviral, Ebola, Interferon, Haemorrhagic, Zoonosis, Transmission

Journal of Microbiology Research 2020, 10(2): 23-44 DOI: 10.5923/j.microbiology.20201002.01 Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever, an Emerging Viral Infection, Epidemiology, Transmission, Pathogenesis and Control - The Nigerian Experience Doughari J. H.1,*, Abubakar I.2 1Department of Microbiology, School of Life Sciences, Modibbo Adama University of Technology, Yola, Nigeria 2Department of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Technology, Federal Polytechnic, Mubi, Nigeria Abstract Ebola haemorrhagic fever (EHF) is a zoonosis affecting both humans and none-human primates (NHP). The fever is caused by Ebola virus, a highly pleomorphic virus of the filovirus family. The virus is a non-segmented negative-stranded RNA virus. Five species of the virus including Zaire ebolavirus, Bundibugyo ebolavirus, Tai Forest ebolavirus (formerly known as Cote d’Ivore), Sudan ebolavirus, and Reston ebolavirus (found in Western Pacific, highly pathogenic in nonhuman primates) have been identified. The recent West African outbreak, which is the biggest since the virus was discovered in 1976, is caused by a new strain, the Zaire ebolavirus. The most recent outbreak of Ebola haemorrhagic fever, the worse ever recorded in the history of the disease was recorded in 2013 in Gueckedou prefecture in Guinea and spread across the bordering Liberia and Sierra Leone. Nigeria, Senegal, Mali and U.S.A recorded imported cases of EVD with the epidemic spanning through 2014, 2015 to early 2016. The onset of the disease is abrupt after an incubation period of two to 21 days followed by clinical -

Non Commercial Use Only

Journal of Public Health in Africa 2016 ; volume 7:534 Ebola viral disease in West African countries. Although interventions by the United Nations and other international Correspondence: Semeeh Akinwale Omoleke, Africa: a threat to global development agencies could ultimately halt the Immunization, Vaccines and Emergencies, World health, economy and political epidemic, local communities must be engaged Health Organization, Kebbi State Field Office, stability to build trust and create demand for the public Nigeria. health interventions being implemented in the E-mail: [email protected] Ebola-ravaged populations. In the intermediate Semeeh Akinwale Omoleke,1 Key words: Ebola viral disease; West Africa; Ibrahim Mohammed,2 Yauba Saidu3 and long term, post-Ebola rehabilitation should Globalization; Drivers of spread; Zoonosis. focus on strengthening of health systems, 1World Health Organization (IVE), improving awareness about zoonosis and Contributions: the authors contributed equally. 2 Nigeria; United Nations Children’s Fund health behaviors, alleviating poverty and miti- 3 (EPI), Nigeria; Clinton Health Access gating the impact of triggering factors. Finally, Conflict of interest: the authors declare no poten- Initiatives, Yaounde, Cameroun national governments and international devel- tial conflict of interest. opment partners should mobilize huge resources and investments to spur or facilitate Received for publication: 22 February 2016. R&D of disease control tools for emerging and Revision received: 4 August 2016. Abstract pernicious infectious diseases (not limited to Accepted for publication: 15 August 2016. EVD). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons The West African sub-continent is currently Attribution NonCommercial 4.0 License (CC BY- experiencing its first, and ironically, the NC 4.0).