VCRD Coffee Value Chain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

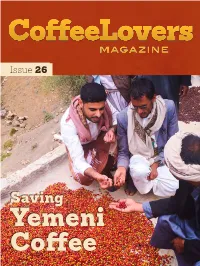

The Journey of One Man Trying to Save Yemeni Coffee (2015)

Issue 26 Saving Yemeni Coffee Coffee at its Origin The journey of one man trying to save Yemeni Coffee Ummah Wide Interviews Mokhtar Alkhanshali of Mocha Mill ummah wide: We are with Mokhtar mokhtar alkhanshali: I was recently talking Alkhanshali, the President and Founder of Mocha to one of my childhood mentors, Nasseam Mill — Yemeni Speciality Coffee, a company with a Elkarra, and he was reminding me that when I powerful social mission that is bridging the worlds was in High School I was always talking about of coffees roots in Yemen with the speciality coffee coffee in Yemen and the history of coffee in industry in the United States. One of the incredible Yemen. In particular he said I was talking things about this project is that you stand at the about the issue of Qat, the locally consumed intersection of two amazing histories, on one side stimulant in Yemen and how it’s taken the place you come from a family who has been growing of coffee in agriculture and someone needs to coffee for hundreds of years in Yemen, the first do something about it. Stephen Ezill, one of place to cultivate and commercialize coffee in the my friends at Boot Coffee said that his brother world. On the other side you are the first Arab/ called me a hero of a thousand faces because Yemeni certified speciality coffee Q grader. What there are so many different ways of looking can you tell us about these two worlds and how at what I am doing and different routes that you came to this moment in your life founding guided me to this point here. -

Roaster Guild Certification Program Handbook

Coffee Taster CERTIFICATE PROGRAM (CT) Ver. 1.0/January 2013 Specialty Coffee Association of America Cupper Guild of America 330 Golden Shore, Suite 50, Long Beach, California 90802 TEL: 562-624-4193 FAX: 562-624-4101 Introduction to the Coffee Taster (CT) Certificate Program Guide Welcome to the CT Certificate Program of Specialty Coffee Association of America. This guide is to provide general information to candidates of the program. It contains background information, definitions, descriptions, and procedures for the program. TABLE OF CONTENTS CT INFORMATION: Background ................................................................................................................... 1 CT CERTIFICATE PROGRAM: Overview, Purpose, Eligibility and Requirements .................................... 2 CT CERTIFICATE PROGRAM: Curriculum Summary .................................................................................. 3 MODULE 1 : Overview ..................................................................................................................................... 4 MODULE 1 : Classes, Rationale and Expectations ...................................................................................... 5 MODULE 2 : Overview ..................................................................................................................................... 6 MODULE 2 : Classes, Rationale and Expectations ...................................................................................... 7 MODULE 3 : Overview .................................................................................................................................... -

Effects of Coffee Roasting Technologies on Bioactive Compounds and Cup Quality of Specialty Coffee Beans Grown in Ethiopia

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY ADDIS ABABA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF CHEMICAL AND BIO-ENGINEERING FOOD ENGINEERING PROGRAMME Effects of Coffee Roasting Technologies on Bioactive Compounds and Cup Quality of Specialty Coffee Beans Grown in Ethiopia A Thesis Submitted to the School of Chemical & Bio-Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (M.Sc.) in Chemical Engineering (Food Engineering) By Muluken Zenebe Bolka November 7, 2019 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Effects of Coffee Roasting Technologies on Bioactive Compounds and Cup Quality of Specialty Coffee Beans Grown in Ethiopia By Muluken Zenebe Bolka A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (M.Sc.) in Chemical Engineering (Food Engineering) School of Chemical and Bio-Engineering Addis Ababa Institute of Technology Addis Ababa University Advisor: Dr. Eng. Shimelis Admassu (Associate Professor) Title Page Copyright © Muluken Z. Bolka, 2019 i Declaration I, the undersigned, declare that this thesis presented for the attainment of the degree of Master of Science in Chemical Engineering (Food Engineering) has been composed solely by myself and has not been presented or submitted, in part or as a whole, for a degree in any other institution or university. The thesis presented is my original work and all sources of information or materials used for the thesis have been duly acknowledged. Mr. Muluken Zenebe Bolka Signature: _______________ Date: ___________________ M.Sc. Candidate This thesis has been submitted for examination with my approval and done under my supervision as University advisor. Dr. Eng. Shimelis Admassu Emire Signature: ______________ Date: ____________________ Advisor The undersigned members of the thesis examining board appointed to examine the thesis of Mr. -

Coffee Flavor and Flavor Attributes That Drive Consumer Liking for These Novel Products

beverages Review Coffee Flavor: A Review Denis Richard Seninde and Edgar Chambers IV * Center for Sensory Analysis and Consumer Behavior, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66502, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 June 2020; Accepted: 3 July 2020; Published: 8 July 2020 Abstract: Flavor continues to be a driving force for coffee’s continued growth in the beverage market today. Studies have identified the sensory aspects and volatile and non-volatile compounds that characterize the flavor of different coffees. This review discusses aspects that influence coffee drinking and aspects such as environment, processing, and preparation that influence flavor. This summary of research studies employed sensory analysis (either descriptive and discrimination testing and or consumer testing) and chemical analysis to determine the impact aspects on coffee flavor. Keywords: coffee flavor; processing; preparation; emotion; environment; consumer acceptance 1. Introduction The coffee market is currently worth USD 15.1 billion and growing. This market is mainly comprised of roasted, instant, and ready-to-drink (RTD) coffee [1]. The flavor of a roasted coffee brew is influenced by factors such as the geographical location of origin, variety, climatic factors, processing methods, roasting process, and preparation methods [2–10]. The differences in sensory properties can, in turn, affect consumers’ preferences for and emotions or attitudes toward coffee drinking [11]. 1.1. Motivations for Drinking Coffee As indicated by Phan [12], the motivations for drinking coffee can be grouped under 17 constructs: liking, habits, need and hunger, health, convenience, pleasure, traditional eating, natural concerns, sociability, price, visual appeal, weight control, affect regulation, social norms, social image [13], choice and variety seeking [12,14,15]. -

Extract Series TEMPLATE: COFFEE & MILK

Extract Series TEMPLATE: COFFEE & MILK THaveaste andyou evercompa tastedre 3 d2i fmilksferent side sugars by sideat 3 anddiffe wonderedrent levels howof refinement, they could t henbe seeso different? how each sugar impacts the flavor of two or more coffees with different flavor profiles. Or had the same coffee at 2 different shops that use different milks and Materials:wondered whyRefined the cappuccinossugar, Turbinado highlighted sugar, Sucanat/Deme totally differentrera/Muscavado flavors? sugar, small tasting cups or spoons for sugars, small tasting cups for coffees, scales,In this exercise,grinders, you’llbrewing compare and service the taste for coof fmilksfees. from 3 different dairies. Prepare like a coffee cupping and have attendees taste with cupping spoons. PEachrovide of thea brief 3 milks introduc shouldtion be of prepared the exercise, cold briefly and steamed. describing Optional: the following: Also prepare each of the 3 milks as a cappuccino with the same coffee/recipe for each. • Why are we doing the exercise • What items will be tasted This exercise• What toworks reflect best upon if you as canyou’ includere tasting at least(sensory 1 totally sensa differenttions, intensity milk. vs. Non-homogonized,flavor) UHT Pasteurization, All Jersey Cows, or something attendees• Best might prac tnotices have for exe accessrcise to (tas att ingtheir o rcafé.der, tasting multiple times, tasting at different dosages) Materials: 3 different milks from 3 different dairies, cupping spoons, glasses Pforrocedu all milkres: samples, buckets for dumping, rinse water, towels, espresso machine equipment for steaming the milk and/or preparing coffee. 1. Taste the sugars. Provide a brief introduction of the exercise, briefly describing the following:• Refined Sugar - Full refinement, only sucrose is left. -

How Business Strategy Is Transforming Rwanda

How Business Strategy is Transforming Rwanda NEAL DONAHUE "Hope is definitely not the same thing as optimism. 'It is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out. -VACLAV HAVEL In July 1994, forces of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) entered Kigali and ended a genocide that took the lives of 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus. The military actions of the RPF, the creation of the government of national unity, and the assistance of international donors restored hope to Rwanda. Millions of displaced people returned to Rwanda and began the effort to rebuild their lives. Over the past decade, Rwanda has used this hope to build a new society and create the foundation of a stable economy. Rwanda's economy grew steadily during the last decade, and the standard of living is slowly improving. The Government of Rwanda has set the target of achieving middle income status by 2020. To achieve this ambitious goal, Rwanda must have a GDP per capita of US$900/year. Assuming the population continues to grow at recent historic rates, Rwanda will have 16 million citizens in 2020. Taken together, that means that the economy of Rwanda must grow from its US$2 billion in 2000 to almost US$14.5 billion in 2020. What can Rwanda do to sustain a required growth rate of 8 percent per year? A nation's standard of living is determined by its productivity-that is, how well its citizens work together to create value for foreign customers and for one another. -

Charlotte's Coffee House

DUBUQUE365.com CHARLOTTE’S COFFEE HOUSE BY RICH BelMONT With new coffee shops popping up all over Dubuque you might Obviously there is a list of coffee beverages to choose from. them to throw in mushrooms not have noticed Charlotte’s Coffee House at the corner of 11th Of course brewed coffee is always available but the real fun and tomatoes too. At lunch and White Streets. It has been in operation for six months and is in trying the specialties. Here are some you might not be time I prefer the Turkey & already has a devoted following of coffee aficionados. familiar with: Dressing Panini. This one has roasted turkey, Monterey Don Rusk and his wife, Espresso (ehss-press-oh) – a strong, thick, syrupy coffee Jack or Swiss cheese, sage Cheryl, are Dubuque natives made by forcing nearly boiling water under pressure through dressing, cranberry sauce and the owners of Charlotte’s tightly packed finely ground coffee beans. and pesto. It was supposed to Coffee House. Don also owns be a seasonal special for Thanksgiving but so many customers and operates Rusk Metal Cappuccino (cap-poo-chee-no) – prepared with espresso, hot kept asking for it they had to add it to the regular menu. Company in Epworth, IA. milk and steamed milk foam. (Fun Fact: the foam on top acts He has been in the metal as an insulator and helps retain the heat of the espresso By the way do you know how we got to enjoy a Panini? Panini business for over 20 years. allowing it to stay hotter longer.) (pah-nee-nee) is the plural of the Italian word Panino or bread Cheryl recently retired from John Deere Dubuque Works where roll. -

Taste, Value, and Power in the Third Wave Coffee Market

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Fischer, Edward F. Working Paper Quality and inequality: Taste, value, and power in the third wave coffee market MPIfG Discussion Paper, No. 17/4 Provided in Cooperation with: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies (MPIfG), Cologne Suggested Citation: Fischer, Edward F. (2017) : Quality and inequality: Taste, value, and power in the third wave coffee market, MPIfG Discussion Paper, No. 17/4, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne, http://hdl.handle.net/11858/00-001M-0000-002C-AA63-2 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/156227 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu MPIfG Discussion Paper 17/4 Quality and Inequality Taste, Value, and Power in the Third Wave Coffee Market Edward F. -

An Investigation of the Shelf Life of Cold Brew Coffee

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2018 An Investigation of the Shelf Life of Cold Brew Coffee nda the Influence of Extraction Temperature Using Chemical Microbial and Sensory Analysis Samuel Nicholas Lopane Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Lopane, Samuel Nicholas, "An Investigation of the Shelf Life of Cold Brew Coffee and the Influence of Extraction Temperature Using Chemical Microbial and Sensory Analysis" (2018). All Theses. 2899. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2899 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN INVESTIGATION OF THE SHELF LIFE OF COLD BREW COFFEE AND THE INFLUENCE OF EXTRACTION TEMPERATURE USING CHEMICAL, MICROBIAL AND SENSORY ANALYSIS A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Food, Nutrition, and Culinary Sciences by Samuel Nicholas Lopane August 2018 Accepted by: Dr. John McGregor, Committee Chair Dr. Paul Dawson Rr. Scott Whiteside ABSTRACT Coffee is a globally popular beverage – it is the second most consumed beverage in the world after tea (Petracco, 2001). According to a report from the National Coffee Association (NCA), in 2018, 64% of US consumers drink coffee daily. The same NCA report in 2017 shows that 59% of all coffee consumed in the US is specialty or gourmet coffee. Within this trend of specialty coffee, a product with rapidly growing market share is cold brew coffee. -

Community Efforts to Aid Guatemala Thinking of Opening a Coffee Shop

FRIDAY, JUNE 22, 2018 Community Efforts to Aid Guatemala Thinking of Opening a Coffee Shop? Automating Excellence with the Cup of Excellence Amsterdam Coffee Map Fresh Resources & Research in the SCA Store A PUBLICATION OF THE SPECIALTY COFFEE ASSOCIATION FRIDAY, JUNE 22, 2018 Daily Edition 4 Schedules: Today at World of Coffee Lectures, Cuppings & Sustainability Forum 5 Today’s Highlights Community Efforts to Aid Guatemala 6 Thinking of Opening a Coffee Shop? Janice Anderson & Dan McCloskey 8 Automating Excellence with the Cup of Excellence Darrin Daniel 9 Amsterdam Coffee Map 11 Fresh Resources & Research in the SCA Store STAFF ON THE COVER JENN RUGOLO Automating Excellence with Executive Editor the Cup of Excellence ZWOELF Design JAMES SHEPHERD Advertising Sales THE DAILY EDITION | FRIDAY, JUNE 22, 2018 3 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Highlights: Friday, June 22 10:00 – 18:00 World Barista Championship Hall 8, RAI Exhibition Centre 10:00 – 17:00 World of Coffee Exhibition Hall 8, RAI Exhibition Centre COFFEE ROASTERS GUILD MIXER World of Coffee Cupping Rooms Meeting Rooms, Ground Floor, RAI science, consumer research, and techniques to apply measurement World of Coffee Lecture Series Meeting Rooms, Ground Floor, RAI Join the Coffee Roasters Guild for an evening of talks and networking tools to specialty coffee before sharing an update on current research 10:45 – 17:00 Sustainability Forum Hall 8, RAI Exhibition Centre from 16:00 to 18:00 at the Guild Lounge. intended to make these tools better: 11:00 – 12:00 in Lecture Room 2 (F003). 16:00 – 18:00 Coffee Roasters Guild Mixer Guild Lounge INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S COFFEE ALLIANCE 18:30 – 20:00 IWCA Evening Reception (ticketed) Rosarium EVENING RECEPTION WORKSHOP: SUSTAINABILITY ESSENTIALS FOR THE COFFEE PROFESSIONAL Join IWCA for an evening reception from 18:30-20:00 at Rosarium LECTURE SERIES featuring drinks, canapes, and an update on IWCA activities. -

Economic Liberalization in Rwanda's Coffee Sector

CHAPTER 1 1 Economic Liberalization in Rwanda’s Coffee Sector: A Better Brew for Success Karol C. Boudreaux n 2008 Solberg and Hansen, a Norwegian importer of income or profits were limited. Starting in the late 1990s, the high-quality specialty coffee, bid just under $40 a kilo- government liberalized the sector, removing a variety of gram (more than 21,000 Rwandan francs) for a load of barriers to trade, creating new incentives for groups and Icoffe e from Rwanda.1 While this bid was exceptional— individuals to invest in coffee production, and facilitating specialty coffee normally sells for between $3 and $4 a entrepreneurship in the coffee industry. kilogram—it also represents a real and positive transfor- Working with the private sector and international mation within Rwanda’s coffee sector. In the not-too- donors, the government of Rwanda has reshaped the coffee distant past, the country was known as a producer of industry: the regulatory framework for production has been mediocre coffee that attracted little attention from dis- modified; more than 100 coffee-washing stations have been criminating importers or consumers.2 Today, Rwandan built; donors have supported the development of market coffee is increasingly recognized as a high-quality prod- links between producers and foreign buyers; cooperatives uct, one for which importers such as Solberg and Hansen have formed; and smallholder farmers are working together and, in turn, consumers are willing to pay a premium. in an effort to improve the quality, marketing, and branding Although the Rwandan economy is diversifying, agricul- of their coffee. ture continues to be the primary source of livelihood for These changes have had important effects on the ground the vast majority of the population. -

Alexela Võtab Selgema Kuju

UUDISED PUHKEPÄEV KOLUMN KONTSERN Naine võib moslemitega Tule ja jää edukalt äri ajada pidu elustab Alexela võtab Toftani müügijuht Merli Randoja müüb islamimaade ärimeestele puittooteid. X10 traditsiooni Sel pühapäeval Vabaduse välja- selgema kuju kul toimuva mustpeade kuuse Rahakalender süütamisega elustatakse riitus, mis märkis keskajal talvepidus- Alexela juht HEITI HÄÄL keskendub pankadele tuste lõppu. X3 Tuleviku kasvu alli- teatas eile, et ettevõte Jaanuari lõpus avaldavad neljanda kvartali tulemu- koondab tütarettevõtted sed SEB, Swedbank ja Nordea. X16–17 kas võiks olla tegutse- ühe katuse alla. Ettevõt- mine keskmisest kiire- te struktuur saab nüüd ka avalikkusele selgemaks, Kullapalavik pole ma kasvuga turgudel. põhjendas ta. Lisaks an- nab selline koondamine raugenud Jurist Martin Mäesalu käib Eduka Eesti konkursi tema sõnul täiendavat fi- Enamik analüütikuid prognoosib, et kuld jätkab rallit raames välja idee, kuidas Eesti võiks pääseda nn nantsvõimekust. X8–9 ka tänavu, kuid osa pelgab, et kulla hind kukub. X20 vaese koera rollist X14 Nädalavahetus EUR/USD USD/EUR EUR/SEK NordPool Euribor ??????????? ??????????? ??????????? ??????????? ??????% Reede, 4. jaanuar 2013 EUR/USD USD/EUR EUR/SEK NordPool Euribor nr 2 (4659) 2,50 eurot 1,3102 0,7632 8,5398 41,08 0,320% Alanud aastal tabab Eestit müügilaine, sest investeerimisfondid soovivad ettevõtetest LUUBI ALL väljuda. Vaata, millised firmad ja mis hinnaga Osta võivad müüki tulla. X 4–7 ettevõte NÄDALA TEGIJA 2 TOIMETUS Sauli Niinistö algatas palgalangetusdebati Kui võrrelda Eesti ja Soome presidendi uus- senti. Niinistö noomis ahneid juhte, kes languse aastakõnet, siis erinevalt meie riigipeast ajal on hoopis rohkem raha krabanud. Presidendi lükkas Sauli Niinistö riigis käima tõsise de- ettepanek leidis suurt toetust nii poliitikute kui ka bati.