Here on This Hill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

80S 697 Songs, 2 Days, 3.53 GB

80s 697 songs, 2 days, 3.53 GB Name Artist Album Year Take on Me a-ha Hunting High and Low 1985 A Woman's Got the Power A's A Woman's Got the Power 1981 The Look of Love (Part One) ABC The Lexicon of Love 1982 Poison Arrow ABC The Lexicon of Love 1982 Hells Bells AC/DC Back in Black 1980 Back in Black AC/DC Back in Black 1980 You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC Back in Black 1980 For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) AC/DC For Those About to Rock We Salute You 1981 Balls to the Wall Accept Balls to the Wall 1983 Antmusic Adam & The Ants Kings of the Wild Frontier 1980 Goody Two Shoes Adam Ant Friend or Foe 1982 Angel Aerosmith Permanent Vacation 1987 Rag Doll Aerosmith Permanent Vacation 1987 Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Permanent Vacation 1987 Love In An Elevator Aerosmith Pump 1989 Janie's Got A Gun Aerosmith Pump 1989 The Other Side Aerosmith Pump 1989 What It Takes Aerosmith Pump 1989 Lightning Strikes Aerosmith Rock in a Hard Place 1982 Der Komimissar After The Fire Der Komimissar 1982 Sirius/Eye in the Sky Alan Parsons Project Eye in the Sky 1982 The Stand Alarm Declaration 1983 Rain in the Summertime Alarm Eye of the Hurricane 1987 Big In Japan Alphaville Big In Japan 1984 Freeway of Love Aretha Franklin Who's Zoomin' Who? 1985 Who's Zooming Who Aretha Franklin Who's Zoomin' Who? 1985 Close (To The Edit) Art of Noise Who's Afraid of the Art of Noise? 1984 Solid Ashford & Simpson Solid 1984 Heat of the Moment Asia Asia 1982 Only Time Will Tell Asia Asia 1982 Sole Survivor Asia Asia 1982 Turn Up The Radio Autograph Sign In Please 1984 Love Shack B-52's Cosmic Thing 1989 Roam B-52's Cosmic Thing 1989 Private Idaho B-52's Wild Planet 1980 Change Babys Ignition 1982 Mr. -

Classic Rock/ Metal/ Blues

CLASSIC ROCK/ METAL/ BLUES Caught Up In You- .38 Special Girls Got Rhythm- AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long- AC/DC Angel- Aerosmith Rag Doll- Aerosmith Walk This Way- Aerosmith What It Takes- Aerosmith Blue Sky- The Allman Brothers Band Melissa- The Allman Brothers Band Midnight Rider- The Allman Brothers Band One Way Out- The Allman Brothers Band Ramblin’ Man- The Allman Brothers Band Seven Turns- The Allman Brothers Band Soulshine- The Allman Brothers Band House Of The Rising Sun- The Animals Takin’ Care Of Business- Bachman-Turner Overdive You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet- Bachman-Turner Overdrive Feel Like Makin’ Love- Bad Company Shooting Star- Bad Company Up On Cripple Creek- The Band The Weight- The Band All My Loving- The Beatles All You Need Is Love- The Beatles Blackbird- The Beatles Eight Days A Week- The Beatles A Hard Day’s Night- The Beatles Hello, Goodbye- The Beatles Here Comes The Sun- The Beatles Hey Jude- The Beatles In My Life- The Beatles I Will- Beatles Let It Be- The Beatles Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)- The Beatles Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da- The Beatles Oh! Darling- The Beatles Rocky Raccoon- The Beatles She Loves You- The Beatles Something- The Beatles CLASSIC ROCK/ METAL/ BLUES Ticket To Ride- The Beatles Tomorrow Never Knows- The Beatles We Can Work It Out- The Beatles When I’m Sixty-Four- The Beatles While My Guitar Gently Weeps- The Beatles With A Little Help From My Friends- The Beatles You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away- The Beatles Johnny B. -

Wildflowers E-Edition

Crawling Back to You A critical and personal breakdown of Tom Petty’s masterpiece, “Wildflowers” by Nick Tavares Static and Feedback editor Static and Feedback | www.staticandfeedback.com | September, 2012 1 September, 2012 Static and Feedback www.staticandfeedback.com ooking at the spine of the CD, it’s would resume, the music would begin, and clear that the color has mutated a I’d lie with my head on my pillow and my L bit through the years, trapped in hands over my stomach, eyes closed. sunbeams by windows and faded from it’s Sometimes, I’d be more alert and reading brown paper bag origins to a pale bluish the liner notes tucked away in the CD’s grey. The CD case itself is in excellent booklet in an effort to take in as much shape save for a few scratches, spared the information about this seemingly magic art cracks and malfunctioning hinges so many form as possible. other jewel boxes have suffered through The first time I listened to Wildflowers, I drops, moves and general carelessness. All was in high school, in bed, laying out in all, the disc holds up rather well. straight, reading along with the lyrics, More often than not, however, it sits inspecting the credits, the thanks and the on the shelf, tucked below a greatest hits photographs included with this Tom Petty collection and above a later album. Thanks solo record. One hour, two minutes and 41 to technology, the more frequent method seconds later, I felt an overwhelming rush, a of play is the simple mp3, broadcasting out warmth that covered my entire body from of a speaker the size of the head of a head to toe and reached back within my pencil’s eraser mounted above the skull to fill my insides. -

Saschawo Kit.Cdr

PRESS KIT Band Bio Runnin' Down A Dream is a tribute band with a band's vision is to combine professional focus on recreating the sound, feel, and charisma musicianship with a fun and forward-thinking of Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers. The band show, which is meant to entertain the audience. focuses on creating authentic and spontaneous The band members are seasoned professional renditions of some of the most classic and well- musicians who have toured overseas and loved tunes from Tom Petty and his band. Their performed to thousands of people. They know repertoire spans the artist's career, from career- what it takes to ignite a fire in the heart of their making highlights to deep cuts and other surprises. audience, and recreate the magic of these Runnin' Down A Dream is the first and only Tom timeless songs, even without exactly looking like Petty & The Heartbreakers tribute in Charlotte. The Tom Petty and his Heartbreakers! Venues played (with old band) Some of the band members used to play together in a party/beach band in Charloe. Together, they decided to share their love for Tom Pey and his music, paying tribute to some of the arst's most beloved hits as well as some of the most amazing fan-favorite deep cuts! The group is acve throughout the Charloe area, bringing Pey's songs to life for the audience. Some of the past references are: • Taste of Charloe 2017, Charloe, NC (Main Stage) • Music in the Park 2017, Georgetown, SC (Opening Act for The Embers) • Jammin' by the tracks 2017, Waxhaw, NC (Main Act) • Suck, Bang and Blow 2016, -

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers 2002.Pdf

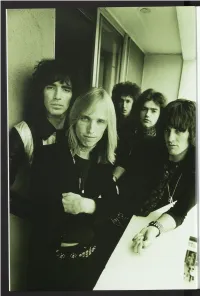

PERFORMERS & THE HEARTBREAKERS By BILL FLANAGAN i t ’s a r a r e t h i n g t o c o m b i n e m a i n s t r e a m s u c c e s s an outdoor concert on Long Island in 1995,1 was with musical substance. To do it while fiercely stand struck by the fact that the crowd was dominated by ing up for personal principles - to the point of wag people in their late teens and early twenties. When I ing public war with your record company - is rarer. mentioned it to Petty afterward, he said he wasn’t To do it for twenty-five years is flat-out remarkable. sure why that was but it sure made him feel good. As A common reaction to the news that Tom Petty I approached a Petty show outside Boston in the and the Heartbreakers are being inducted into the summer of 2001, kids were coming out of the woods, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame has been “They’re a great across fields, holding up signs pleading for tickets. band, but aren’t they too young to qualify?” It’s a Going into the venue, I heard one college-age fan shock to realize that it has been twenty-five years say, “Now that Phish is gone, I follow Petty.” since “Breakdown” and “American Girl.” Petty and The show I saw that night was as strong, as full of the Heartbreakers have never stopped life and energy, as any of the great con Clockwise from front: certs I saw the Heartbreakers play in the long enough to lookback. -

Sounding Board

The Observer • Augustana College • Rock Island, IL • Friday, Sept. 23,1994 SOUNDING BOARD In Love winter. me fans ot his music. with ali of the new and different cover art gives some idea of the Jazz Passengers "You Got Lucky" may have bands out there. consequences of such openness. BMG Distribution Grade: B+ been an appropriate phrase to de- Yellow No. 5 was recorded at a Naked bodies strapped in barbed — Jessica Hinderliter scribe Petty's career, but they blitzkrieg weekend session, and wire grace the CDs liner notes. The Jazz Passengers' latest re- weren't very lucky when they engineered to perfection by drum- The nine-song álbum (a bit short lease, In Love is now on the street. You Got Lucky made this álbum. There were good mer Tony Lash. by recent standards) opens with the In Love is the sixth disc to be A Tribute to Tom Petty songs and bad songs, but more bad The best thing about the music title track. "Dance Naked" begins released by this group who had its Backyard Records than good. If you really want to is the beat. From the opening track, with the command, "I want you to beginnings as members of John hear Tom Petty music, I suggest "Wake," to the closing number, dance naked, so I can see you." Lurie's Lounge Lizards. They re- First of ali, I have to admit, I am you buy his original albums. Júnior Mint — a bonified crowd With that done, the possibility of leased their not the biggest fan of tribute al- pleaser from tour past. -

5F56f037b22ecfa74a1b1346 CM

Tom Petty’s career has touched millions of fans, earned him a place in the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame, a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame and several Grammy nominations. His popularity continues to grow with every new SONG LIST generation of fans and his remarkable list of hit songs are celebrated by audiences everywhere. LISTEN TO HER HEART YOU GOT LUCKY Prior to Tom’s untimely death in 2017, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers toured INTO THE GREAT WIDE OPEN and recorded for over 40 years. They engaged in combat with their various record labels, sang about the woes and shortcomings of the music industry in LEARNIN’ TO FLY general and the radio stations of the day in particular, and in the process KINGS HIGHWAY sold more than 80 million records worldwide. Since 1976, no artist had defined YOU DON’T KNOW HOW IT FEELS “cool” better than Tom Petty, and no band had created a more magical sound HERE COMES MY GIRL together than the spine-chilling perfection that is the Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers song anthology, spanning four decades and touching the lives DON’T DO ME LIKE THAT of millions of Americans many times over. Tom petty was truly one of the great I WON’T BACK DOWN American songwriters. IT’S A GOOD THING TO BE KING Since 1992 FULL MOON FEVER, America’s premier Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers REFUGEE tribute band, has brought to life an energetic and ultra-realistic performance DON’T COME AROUND NO MORE of the legendary rock band. -

Artist Title

O'Shuck Song List Ads Sept 2021 2021/09/20 Artist Title & The Mysterians 96 Tears (Hed) Planet Earth Bartender ´til Tuesday Voices Carry 10 CC I´m Not In Love The Things We Do For Love 10 Years Wasteland 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night More Than This These Are The Days Trouble Me 112 Dance With Me (Radio Version) Peaches And Cream (Radio Version) 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 12 Stones We Are One 1910 Fruitgum Co. 1, 2, 3 Red Light 2 Live Crew Me So Horny We Want Some PUSSY (EXPLICIT) 2 Pac California Love (Original Version) Changes Dear Mama Until The End Of Time (Radio Version) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man (EXPLICIT) 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Be Like That (Radio Version) Here Without You It´s Not My Time Kryptonite Landing In London Let Me Go Live For Today Loser The Road I´m On When I´m Gone When You´re Young (Chart Buster) Sorted by Artist Page: 1 O'Shuck Song List Ads Sept 2021 2021/09/20 Artist Title When You´re Young (Pop Hits Monthly) 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 311 All Mixed Up Amber Down Love Song 38 Special Caught Up In You Hold On Loosely Rockin´ Into The Night Second Chance Teacher, Teacher Wild-eyed Southern Boys 3LW No More (Baby I´ma Do Right) (Radio Version) 3oh!3 Don´t Trust Me 3oh!3 & Kesha My First Kiss 4 Non Blondes What´s Up 42nd Street (Broadway Version) 42Nd Street We´re In The Money 5 Seconds Of Summer Amnesia 50 Cent If I Can´t In Da Club Just A Lil´ Bit P.I.M.P. -

Killer Karaoke Song Book

Killer Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID Al Green Donna Summer Love And Happiness KK5004-02 She Works Hard For The Money KK5003-01 Al Green (Wvocal) Donna Summer (Wvocal) Love And Happiness KK5004-11 She Works Hard For The Money KK5003-09 Betty Wright Doors, The Clean Up Woman KK5003-06 Break On Through KK7004-01 Betty Wright (Wvocal) Hello, I Love You KK7004-04 Clean Up Woman KK5003-14 L.A. Woman KK7004-06 Bruce Springsteen Love Her Madly KK7004-09 Bobby Jean KK7002-08 Love Me Two Times KK7004-03 Born In The USA KK7001-06 People Are Strange KK7004-02 Born To Run KK7002-01 Riders On The Storm KK7004-07 Brilliant Disguise KK7001-05 Roadhouse Blues KK7004-05 Dancing In The Dark KK7001-03 Touch Me KK7004-08 Glory Days KK7001-07 Doors, The (Wvocal) Hungry Heart KK7002-05 Break On Through KK7004-10 I'm A Rocker KK7002-09 Hello, I Love You KK7004-13 I'm On Fire KK7002-07 L.A. Woman KK7004-15 My Hometown KK7001-04 Love Her Madly KK7004-18 No Surrender KK7001-08 Love Me Two Times KK7004-12 Out In The Street KK7002-02 People Are Strange KK7004-11 Prove It All Night KK7002-03 Riders On The Storm KK7004-16 Rosalita (Come Out Tonight) KK7002-04 Roadhouse Blues KK7004-14 Secret Garden KK7001-01 Touch Me KK7004-17 Streets Of Philadelphia KK7001-02 Eddie Floyd Thunder Road KK7002-06 Knock On Wood KK5004-08 Bruce Springsteen (Wvocal) Eddie Floyd (Wvocal) Bobby Jean KK7002-17 Knock On Wood KK5004-17 Born In The USA KK7001-14 Edwin Starr Born To Run KK7002-10 War KK5001-05 Brilliant Disguise KK7001-13 Edwin Starr -

Top Dance Songs Chart of 1983

THE TOP DANCE RYTHYM SONGS OF 1983 1. BILLIE JEAN/BEAT IT- Michael Jackson (Epic) 51. WET MY WHISTLE/FREAK-A-ZOID - Midnight Star (Solar) 2. SO MANY MEN, SO LITTLE TIME - Miquel Brown (TSR) 52. THE MUSIC'S GOT ME - Visual (Prelude) 3. 1'M SO EXCITED - Pointer Sisters (Planet) 53. YOU CAN'T HIDE - David Joseph (Mango) 4. MANIAC-Michael Sembello (Casablanca) 54. TELL ME LOVE - Michael Wycoff (RCA) 5. FLASHDANCE...WHAT A FEELING - Irene Cara (Casablanca) 55. WORK ME OVER - Claudia Barry (TSR) 6. SHE WORKS HARD FOR THE MONEY - Donna Summer (Mercury) 56. ALL I NEED/DON'T STOP/TELL ME - Sylvester (Megatons) 7. HOLIDAY - Madonna (Sire) 57. COLD BLOODED - Rick James (Gordy) 8. LET THE MUSIC PLAY - Shannon (Emergency/Mirage) 58. CRAZY - The Manhattans (Columbia) 9. I.O.U. - Freeez (Streetwise) 59. SO WRONG - Patrick Simmons (Elektra) 10. WANNA BE STARTIN' SOMETHING - Michael Jackson (Epic) 60. REACH OUT - Narada Michael Walden (Atlantic) 11. AIN'T NOBODY - Rufus With Choke Khan (Warner Bros.) 61. I WANT YOU ALL NIGHT - Curtis Hairston (Pretty Pearl) 12. JUST BE GOOD TO ME - SOS Band (Tabu) 62. GET IT RIGHT -Aretha Franklin (Arista) 13. ONE MORE SHOT -C-Bank (Next Plateau) 63. LIFE IS SOMETHING SPECIAL- N.Y. City Peech Boys (Island) 14. ELECTRIC AVENUE- Eddy Grant (Portrait) 64. ALL OVER YOUR FACE - Ronnie Dyson (Cotillion) 15. 1999/LITTLE RED CORVETTE - Prince (Warner Bras.) 65. MOMENT OF MY LIFE/I LIKE IT LIKE THAT - Inner-Life (Salsoul) 16. ALL NIGHT LONG - Lionel Richle (Motown) 66. BUILD ME A BRIDGE - Adele Bertel (Geffen) 17. -

Soul Fish Set List

SOUL FISH SET LIST Club Set/ Favorites These are songs we’ve performed in high energy dance clubs and bars along with some fan favorites. This set is a guaranteed good time. Caught Up In You- .38 Special Dancing Queen- ABBA You Shook Me All Night Long- AC/DC Summer Of 69- Bryan Adams Boom Boom- Big Head Todd & The Monsters/ John Lee Hooker I Gotta Feeling- Black Eyed Peas Livin’ On A Prayer- Bon Jovi Chicken Fried- Zac Brown Band Toes- Zac Brown Band Whatever It Is- Zac Brown Band Folsom Prison Blues- Johnny Cash Ring Of Fire- Johnny Cash Drink In My Hand- Eric Church You Never Even Called Me By My Name- David Allan Coe Hanginaround- Counting Crows Mr. Jones- Counting Crows Pour Some Sugar On Me- Def Leppard Take Me Home, Country Roads- John Denver Sweet Caroline- Neil Diamond She Drives Me Crazy- Fine Young Cannibals Cruise- Florida Georgia Line Pumped Up Kicks- Foster The People Build Me Up, Buttercup- The Foundations Slide- Goo Goo Dolls Basket Case- Green Day Sweet Child O Mine- Guns ‘N’ Roses All She Wants To Do Is Dance- Don Henley The Boys Of Summer- Don Henley It’s 5 O’ Clock Somewhere- Alan Jackson Laid- James Any Way You Want It- Journey Don’t Stop Believin’- Journey Lights- Journey Sweet Home Alabama- Lynyrd Skynyrd Rude- Magic! Moves Like Jagger- Maroon 5 Sunday Morning- Maroon 5 This Love- Maroon 5 Locked Out Of Heaven- Bruno Mars Ants Marching- Dave Matthews Band Cherry Bomb- John Mellencamp Hurts So Good- John Mellencamp Small Town- John Mellencamp Take Me Home Tonight- Eddie Money Brown Eyed Girl- Van Morrison The Cave- -

Tom Petty Sample Page.Vp

G DEBUT PEAK WKS O ARTIST L DATE POS CHR D Album Title Label & Number PETTY, Tom, And The Heartbreakers 1980s: #25 / 1990s: #25 / All-Time: #79 Born on 10/20/1950 in Gainesville, Florida. Died of a heart attack on 10/2/2017 (age 66). Rock singer/songwriter/guitarist. Formed The Heartbreakers in Los Angeles, California: Mike Campbell (guitar; born on 2/1/1950), Benmont Tench (keyboards; born on 9/7/1953), Ron Blair (bass; born on 9/16/1948) and Stan Lynch (drums; born on 5/21/1955). Howie Epstein (born on 7/21/1955; died of a drug overdose on 2/23/2003, age 47) replaced Blair in 1982; Blair returned in 2002, replacing Epstein. Steve Ferrone replaced Lynch in 1995. Scott Thurston (of The Motels) joined as tour guitarist in 1991 and eventually became a permanent member of the band. Petty appeared in the movies FM, Made In Heaven and The Postman and also voiced the character of Elroy “Lucky” Kleinschmidt on the animated TV series King Of The Hill. Member of the Traveling Wilburys. Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers were the subject of the 2007 documentary film Runnin’ Down A Dream, directed by Peter Bogdanovich. One of America’s favorite rock bands of the past five decades; they had wrapped up a 40th Anniversary concert tour shortly before Petty’s sudden death. Also see Mudcrutch. AWARDS: R&R Hall of Fame: 2002 Billboard Century: 2005 9/24/77+ 55 42 G 1 Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers................................................................................................................................. Shelter 52006 6/10/78 23 24 G 2 You’re Gonna Get It! ..................................................................................................................................................