The Relationship Between Flow and Music Performance Level of Undergraduates in Exam Situations: the Effect of Musical Instrument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Romanian Music for Unaccompanied

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KU ScholarWorks CONTEMPORARY ROMANIAN MUSIC FOR UNACCOMPANIED CLARINET BY 2009 Cosmin Teodor Hărşian Submitted to the graduate program in the Department of Music and Dance and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________ Chairperson Committee Members ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ Date defended 04. 21. 2009 The Document Committee for Cosmin Teodor Hărşian certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: CONTEMPORARY ROMANIAN MUSIC FOR UNACCOMPANIED CLARINET Committee: ________________________ Chairperson ________________________ Advisor Date approved 04. 21. 2009 ii ABSTRACT Hărșian, Cosmin Teodor, Contemporary Romanian Music for Unaccompanied Clarinet. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2009. Romanian music during the second half of the twentieth century was influenced by the socio-politic environment. During the Communist era, composers struggled among the official ideology, synchronizing with Western compositional trends of the time, and following their own natural style. With the appearance of great instrumentalists like clarinetist Aurelian Octav Popa, composers began writing valuable works that increased the quality and the quantity of the repertoire for this instrument. Works written for clarinet during the second half of the twentieth century represent a wide variety of styles, mixing elements from Western traditions with local elements of concert and folk music. While the four works discussed in this document are demanding upon one’s interpretative abilities and technically challenging, they are also musically rewarding. iii I wish to thank Ioana Hărșian, Voicu Hărșian, Roxana Oberșterescu, Ilie Oberșterescu and Michele Abbott for their patience and support. -

Full Volume 22

Ethnomusicology Review 22(1) From the Editors Samuel Lamontagne and Tyler Yamin Welcome to Volume 22, issue 1 of Ethnomusicology Review! This issue features an invited essay along with three peer-reviewed articles that cover a wide range of topics, geographical areas, methodological and theoretical approaches. As it seems to be a characteristic of ethnomusicology at large, this variety, even if it has become an object of critical inquiry itself (Rice, 1987, 2007; Laborde, 1997), has allowed the discipline, by grounding itself in reference to the context of study, to not take “music” for granted. It is in this perspective that we’d like to present this volume, and the variety of its contributions. In his invited essay, Jim Sykes asks what ramifications of the Anthropocece, understood as a socio-ecological crisis, hold for the field of music studies and the politics of its internal disciplinary divisions. Drawing upon scholars who assert that the Anthropocene demands not only concern about our planet’s future but also critical attention towards the particular, historically situated ontological commitments that engendered this crisis, Sykes argues that music studies both depends on and reproduces a normative model of the world in which music itself occupies an unproblematized metaphysical status—one that, furthermore, occludes the possibility of “reframe[ing] music history as a tale about the maintenance of the Earth system” (14, this issue) urgently necessary as anthropogenic climate change threatens the continuation of life as usual. By taking seriously the material and discursive aspects of musical practice often encountered ethnographically, yet either explained away by “the worldview embedded in our disciplinary divisions or . -

Krannert Center Debut Artist: Yunji Shim, Soprano

KRANNERT CENTER DEBUT ARTIST: YUNJI SHIM, SOPRANO HANA LIM, PIANO Sunday, April 23 at 3pm Foellinger Great Hall PROGRAM KRANNERT CENTER DEBUT ARTIST: YUNJI SHIM, SOPRANO Hana Lim, piano Reynaldo Hahn A Chloris (1874-1947) Fêtes galantes L’Énamourée Le Printemps Richard Strauss Four Songs, Op. 27 (1864-1949) Ruhe, meine Seele! Heimliche Aufforderung Morgen! Cäcilie Stefano Donaudy Amorosi miei giorni (1879-1925) O del mio amato ben Luigi Arditi Il bacio (1822-1903) 20-minute intermission Sergei Rachmaninoff Coнъ (A dream) Op.8, No.5 (1873-1943) Не пой, красавица! (Oh, never sing to me again) Op.4 No. 4 Здесь хорошо (How fair this spot!) Op. 21 No.7 Весенние воды (spring waters) Op.14 No.11 Ernest Charles When I have sung my songs (1895-1984) And so, goodbye Let my song fill your heart 2 THE ACT OF GIVING OF ACT THE THANK YOU TO THE SPONSORS OF THIS PERFORMANCE Krannert Center honors the spirited generosity of these committed sponsors whose support of this performance continues to strengthen the impact of the arts in our community. * LOUISE ALLEN Ten Previous Sponsorships * * BARBARA & TERRY ENGLAND NADINE FERGUSON One Previous Sponsorship Seven Previous Sponsorships *PHOTO CREDIT: ILLINI STUDIO JOIN THESE INSPIRING DONORS BY CONTACTING OUR DEVELOPMENT TEAM TODAY: KrannertCenter.com/Give • [email protected] • 217.333.1629 3 PROGRAM NOTES REYNALDO HAHN This collection offered by Yunji Shim and Hana Born August 9, 1875, in Caracas, Venezuela Lim thus covers over twenty years of Hahn’s Died January 28, 1947, in Paris, France compositional life plus his long-held interest in À Chloris French poetry from both the Baroque Period and Fêtes galantes the 19th century. -

12 September 2021

12 September 2021 12:01 AM Joseph Lanner (1801-1843) Old Viennese Waltzes Arthur Schnabel (piano) SESR 12:07 AM Flor Alpaerts (1876-1954) Zomer-idylle (1928) Flemish Radio Orchestra, Michel Tabachnik (conductor) BEVRT 12:15 AM Franz Schubert (1797-1828),Max Reger (1873-1916) Am Tage aller Seelen D 343 Dietrich Henschel (baritone), National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Jerzy Semkow (conductor) PLPR 12:22 AM Alessandro Marcello (1673-1747) Concerto in D minor for oboe and strings Maja Kojc (oboe), RTV Slovenia Symphony Orchestra, Pavle Despalj (conductor) SIRTVS 12:34 AM Ernst Linko (1889-1960) Concerto No.2 for piano and orchestra (Op.10) Raija Kerpo (piano), Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Osmo Vanska (conductor) FIYLE 12:54 AM Jose de Nebra (1702-1768) Entre cándidos Maria Espada (soprano), Al Ayre Espanol, Eduardo Lopez Banzo (harpsichord) PLPR 01:09 AM Antonin Dvorak (1841-1904) String Quartet No 12 in F major 'American', Op 96 Prague Quartet NLNOS 01:32 AM Sergey Prokofiev (1891-1953) Lieutenant Kije - suite for orchestra, Op 60 Queensland Symphony Orchestra, Vladimir Verbitsky (conductor) AUABC 01:54 AM Niccolo Paganini (1782-1840) Caprice no 24 in A minor Sergei Krylov (violin) HRHRTR 02:01 AM Samuel Barber (1910-1981) Adagio for strings, Op 11 WDR Symphony Orchestra, Cologne, Cristian Macelaru (conductor) DEWDR 02:10 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Violin Concerto no 5 in A, K.219 ('Turkish') Pinchas Zukerman (violin), WDR Symphony Orchestra, Cologne, Cristian Macelaru (conductor) DEWDR 02:39 AM Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) -

Syntaxes and Sonorous Systems in Five Pieces for Orchestra by Sabin Pautza

Latest Advances in Acoustics and Music Syntaxes and Sonorous Systems in Five Pieces for Orchestra by Sabin Pautza ANCA LEAHU Department of Music University of Arts George Enescu, Iasi Str. Horia, nr. 7-9 ROMANIA [email protected] Abstract: In Five Pieces for Orchestra, the composer Sabin Pautza focuses on the idea of exploring all the syntaxes, from the accompanied monody, polyphony, homophony and heterophony to various combinations of them. This idea serves a modal-serial organization, based on mathematical formulas and incorporates all the elements of language, such as melody, rhythm, harmony and dynamics. Applying these mixed types of syntaxes (homogeneous or heterogeneous) to a large orchestra generates rich sonorous pages where the texture comes first. Key-Words: Syntaxes, sonorous systems, Sabin Pautza, texture, natural resonance, total chromatic, modal-serial organization. Introduction relating to an overall meaning with respect to the Although structured in five parts (composed in references to those sonorities stemming from 1971), this work is focused on a sound construction Romanian folk music. that claims its aesthetic meanings especially on a macro formal level. The alternation applied to syntax, metrics, dynamics, tempos and moods Piece I conveyed becomes the compositional principle upon The first piece starts with an accompanied which the Five Pieces for Orchestra [1] are built. monody (fig. 1) and reaches a texture with various Sabin Pautza’s [2] idea of exploring all the plans. syntaxes, starting from accompanied monody, polyphony, homophony and heterophony to various Fig. 1 (S. Pautza – Five Pieces for Orchestra, combinations between them, serves a modal-serial movt. I, pg. -

Annual Report 2017–18

Annual Report 2017–18 1 3 Introduction 5 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 7 Season Repertory and Events 13 Artist Roster 15 The Financial Results 48 Our Patrons 2 Introduction During the 2017–18 season, the Metropolitan Opera presented more than 200 exiting performances of some of the world’s greatest musical masterpieces, with financial results resulting in a very small deficit of less than 1% of expenses—the fourth year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so. The season opened with the premiere of a new staging of Bellini’s Norma and also included four other new productions, as well as 19 revivals and a special series of concert presentations of Verdi’s Requiem. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 12th year, with ten broadcasts reaching more than two million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (box office and media) totaled $114.9 million. Total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. All five new productions in the 2017–18 season were the work of distinguished directors, three having had previous successes at the Met and one making an auspicious company debut. A veteran director with six prior Met productions to his credit, Sir David McVicar unveiled the season-opening new staging of Norma as well as a new production of Puccini’s Tosca, which premiered on New Year’s Eve. The second new staging of the season was also a North American premiere, with Tom Cairns making his Met debut directing Thomas Adès’s groundbreaking 2016 opera The Exterminating Angel. -

17 June 2021

17 June 2021 12:01 AM Wojciech Kilar (1931-2013) Little Overture (1955) National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Stanislav Macura (conductor) PLPR 12:08 AM Francesco Durante (1684-1755) Concerto per quartetto for strings No.4 in E minor Concerto Koln DEWDR 12:19 AM Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Laudate Pueri (motet, Op 39 no 2) Polyphonia, Ivelina Ivancheva (piano), Ivelin Dimitrov (conductor) BGBNR 12:28 AM Dobrinka Tabakova (b.1980) Pirin for viola (2000) Maxim Rysanov (viola) GBBBC 12:37 AM Johann Baptist Georg Neruda (1708-1780) Concerto for horn or trumpet and strings in E flat major Tine Thing Helseth (trumpet), Oslo Camerata, Stephan Barratt-Due (conductor) NONRK 12:53 AM Marin Marais (1656-1728) Tombeau pour Monsr. de Lully Ricercar Consort, Henri Ledroit (conductor) NLNOS 01:01 AM Bela Bartok (1881-1945) Concerto for orchestra, Sz116 Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Erich Leinsdorf (conductor) NLNPB 01:38 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Partita in E flat (K.Anh.C 17`1) Festival Winds CACBC 02:01 AM Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Symphony No.4 in A major, Op.90 (Italian) Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Thomas Guggeis (conductor) SESR 02:31 AM Ottorino Respighi (1897-1936) Pines of Rome Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Thomas Guggeis (conductor) SESR 02:54 AM Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) Messa di Gloria Boyko Tsvetanov (tenor), Alexander Krunev (baritone), Dimitar Stanchev (bass), Bulgarian National Radio Chorus, Bulgarian National Radio Symphony Orchestra, Milen Nachev (conductor) BGBNR 03:38 AM Ottorino Respighi (1897-1936) -

Contemporary Romanian Music For

CONTEMPORARY ROMANIAN MUSIC FOR UNACCOMPANIED CLARINET BY 2009 Cosmin Teodor Hărşian Submitted to the graduate program in the Department of Music and Dance and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________ Chairperson Committee Members ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ Date defended 04. 21. 2009 The Document Committee for Cosmin Teodor Hărşian certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: CONTEMPORARY ROMANIAN MUSIC FOR UNACCOMPANIED CLARINET Committee: ________________________ Chairperson ________________________ Advisor Date approved 04. 21. 2009 ii ABSTRACT Hărșian, Cosmin Teodor, Contemporary Romanian Music for Unaccompanied Clarinet. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2009. Romanian music during the second half of the twentieth century was influenced by the socio-politic environment. During the Communist era, composers struggled among the official ideology, synchronizing with Western compositional trends of the time, and following their own natural style. With the appearance of great instrumentalists like clarinetist Aurelian Octav Popa, composers began writing valuable works that increased the quality and the quantity of the repertoire for this instrument. Works written for clarinet during the second half of the twentieth century represent a wide variety of styles, mixing elements from Western traditions with local elements of concert and folk music. While the four works discussed in this document are demanding upon one’s interpretative abilities and technically challenging, they are also musically rewarding. iii I wish to thank Ioana Hărșian, Voicu Hărșian, Roxana Oberșterescu, Ilie Oberșterescu and Michele Abbott for their patience and support. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION…………………………. -

George Enescu

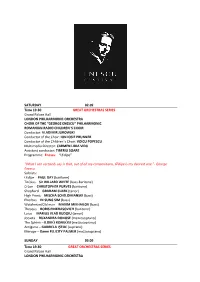

SATURDAY 02.09 Time 19.30 GREAT ORCHESTRAS SERIES Grand Palace Hall LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA CHOIR OF THE “GEORGE ENESCU” PHILHARMONIC ROMANIAN RADIO CHILDREN’S CHOIR Conductor: VLADIMIR JUROWSKI Conductor of the Choir: ION IOSIF PRUNNER Conductor of the Children’s Choir: VOICU POPESCU Multimedia Director: CARMEN LIDIA VIDU Assistant conductor: TIBERIU SOARE Programme: Enescu – “Œdipe” “What I can certainly say is that, out of all my compositions, Œdipe is my dearest one.”- George Enescu Soloists: Œdipe – PAUL GAY (baritone) Tirésias – Sir WILLARD WHITE (bass-baritone) Créon – CHRISTOPHER PURVES (baritone) Shephard – GRAHAM CLARK (tenor) High Priest – MISCHA SCHELOMIANSKI (bass) Phorbas – IN SUNG SIM (bass) Watchman/Old man – MAXIM MIKHAILOV (bass) Theseus – BORIS PINKHASOVICH (baritone) Laius – MARIUS VLAD BUDOIU (tenor) Jocasta – RUXANDRA DONOSE (mezzosoprano) The Sphinx – ILDIKÓ KOMLÓSI (mezzosoprano) Antigone – GABRIELA IŞTOC (soprano) Mérope – Dame FELICITY PALMER (mezzosoprano) SUNDAY 03.09 Time 19.30 GREAT ORCHESTRAS SERIES Grand Palace Hall LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA Conductor: VLADIMIR JUROWSKI Soloist: CHRISTIAN TETZLAFF – violin Programme: Wagner – “Tristan und Isolde”. Prelude to Act 3 Berg – Concerto for violin and orchestra (1935) Shostakovich – Symphony No.11 in G minor Opus. 103 (1905) MONDAY 04.09 Time 20.00 GREAT ORCHESTRAS SERIES Grand Palace Hall RUSSIAN NATIONAL ORCHESTRA RADIO ACADEMIC CHOIR Conductor: MIKHAIL PLETNEV Conductor of the choir: CIPRIAN ȚUȚU Soloist: NIKOLAI LUGANSKY – piano Programme: Enescu – “Isis” Poem (1923, orchestrated by Pascal Bentoiu, according to the composer's sketches) “The Isis poem is a mysterious work, impregnated with Œdipe effluvia, as well as an unmistakeable Tristanesque air, and – while it is no “music portrait” – it probably contains a tribute […] of the author to the person he loved most in this lifetime.” (Pascal Bentoiu, Breviar enescian) Prokofiev – Concerto no. -

Voices in Space Or the Contemporary Realism in the Pedagogy of the Future Opera Singer

DOI: 10.2478/ajm-2021-0014 Artes. Journal of Musicology Voices in Space or the Contemporary Realism in the Pedagogy of the Future Opera Singer DUMITRIANA CONDURACHE, Lecturer, PhD CONSUELA RADU-ȚAGA, Lecturer, PhD “George Enescu” National University of Arts Iași ROMANIA ∗ Abstract: The Romanian opera and operetta repertoire is a constant objective in the Opera Class of the Faculty of Performing, Composition, and Musical Theoretical Studies in “George Enescu” National University of Arts from Iași. The stylistic diversity and the richness of the drama make not only an important instrument for the study out of it, but also a moral debt for the knowledge and transmission of a music whose beauty – once (re)discovered – is a source of enchantment for the artists, as well as for the public. If in the beginning of the professional route singing in the mother tongue facilitates the work and the study of the opera singer, over time this option may enter an ethic of the performer, happily completing his repertoire. Although one of our main goals is to guide the students, future opera singers, to gain and to develop their acting skills so as to be natural and convincing on stage, contemporary realism does not exclude experiments. Having this in mind and in order to make studentsʼ work visible, we made an experimental video document, based on a first selection from our recitals, which is aimed to let the audience take a glance into the intimacy of our class study on Romanian opera and operetta, both from the musical and drama perspective. By changing the original objective – the entire presentation in semester exams of studentsʼ classroom work – the fragmentary nature of the processing gives a certain dynamism to our work. -

02 Current Works List

Aaron Holloway-Nahum Works List | Page 1 of 6 LIST OF WORKS WITH PREMIERE PERFORMANCES LARGE ENSEMBLE (9+ PLAYERS, INCLUDING ORCHESTRA) Te Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst [Upcoming: 2022] - 80 minutes Chamber Opera based on the true story of Donald Crowhurst. Libretto by Peter Jones, Direction by Ella Marchment Baritone, Countertenor, Clarinets, Trombone, Accordion, Percussion and Double Bass with video playback Henani [Upcoming: 2021] - 20 minutes • Commissioned by Ensemble Echappe, for harpists Emily Levin and Ben Melsky • Premiere Slated for Autumn 2020 2 Solo Harps/1.1.1.1/Sax/1.1.1.1/Perc/Pno/Str=1.1.1.1.1 Vernichtung - Concerto for Bass Clarinet - 20 minutes • Commissioned by the Pannon Philharmonic Orchestra, Toby Tatcher Conducting • Premiered 14 Nov 2019, Horia Dumitrache, Soloist 1.1.1.1.TenSax/4.2.1.1/2perc/acc/str=10.8.8.6.5 with solo bass clarinet Like a Memory of Birds II (2019) - 12 minutes • Commissioned by Plural Ensemble (Madrid) and Peter Eötvös • Premiered 17 April, 2019 2 Cl(II=bass)/0.1.1.1/Perc/Pno/Str=1.1.1.1.1 Anything but Real Time (2015) - 8 minutes • Commissioned by the London Symphony Orchestra • Premiered LSO St. Luke’s 17 April, 2015, Aaron Holloway-Nahum Conducting Fl, Bass Cl, Horn, Bb Trpt, Perc, Str = 1.1.1.1.1 Fantasies of Management (2014) - 5 Minutes • Commissioned for the 2014 Aspen Music Festival • Premiere July 2014, Harris Hall, AACA Orchestra, George Jackson Conductor 2222/4331/2perc/Harp/Pno(=Celesta)/Strings=12.10.8.8.6 Te Deeper Breath to Follow (2013) – 11 Minutes • Commissioned by the BBC Symphony Orchestra & Sound and Music • Premiere 14 Nov. -

05 November 2020

05 November 2020 12:01 AM Bela Bartok (1881-1945) Evening in Transylvania and Swineherd's Dance, from 'Hungarian Pictures, Sz. 97' Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra, Zsolt Hamar (conductor) CHSRF 12:06 AM Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) Serenata in vano (FS.68) Kari Kriikku (clarinet), Jonathan Williams (horn), Per Hannisdahl (bassoon), oystein Sonstad (cello), Katrine oigaard (double bass) NONRK 12:14 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) Impromptu in F sharp major, Op 36 Krzysztof Jablonski (piano) PLPR 12:19 AM Jonas Tamulionis (1949-), Justinas Marcinkevicius (author) Domestic Psalms Polifonija, Unknown (soprano), Sigitas Vaiciulionis (conductor) LTLR 12:27 AM Dinu Lipatti (1917-1950) Piano Concertino, 'en style ancien', Op 3 Horia Mihail (piano), Romanian Radio Chamber Orchestra, Horia Andreescu (conductor) ROROR 12:44 AM Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) Quartet no.12 in E minor, TWV.43:e4 'Paris Quartet' (1738) no.6 Nevermind PLPR 01:03 AM Juan Crisostomo Arriaga (1806-1826) Erminia, scene lyrique-dramatique for soprano and orchestra Rosamund Illing (soprano), Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, Heribert Esser (conductor) AUABC 01:17 AM Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) Holberg Suite, Op 40 Zurich Chamber Orchestra, Willi Zimmermann (conductor) CHSRF 01:38 AM Anonymous 2 Songs: "Fortune, my foe" for solo voice & "Go and catch" for voice and lute Paul Agnew (tenor), Christopher Wilson (lute) ATORF 01:43 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Symphony No 31 in D major, 'Paris', K297 Danish Radio Sinfonietta, Adam Fischer (conductor) DKDR 02:01 AM Richard