A New Approach to Gaudapadakarika

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Search of Beef Producton Nirvana

Chip Ramsay, Rex Ranch June 16, 2016 Nirvana: What does that mean? In Search of Beef Produc0on Nirvana • In the Buddhist tradi5on, nirvana is described as the ex5nguishing of the fires that cause suffering and rebirth.[29] These fires are typically iden5fied as the fires of aachment (raga), aversion (dvesha) and ignorance (moha or avidya). • In Hindu philosophy, it is the union with Brahman, the divine ground of existence, and the experience of blissful Things a cow-calf producer learns when you egolessness.[8] own a feedyard: what drives profit? Challenges we face: Rex Ranch • Weather volality •Price volality • Trust between segments • Adding real value to our produc5on • Answers come excruciangly slow (Environment or Genec?) • 2 year concep5on to harvest Excel Beef •7 year gene5c interval Deseret Cattle • Applying research findings correctly in various systems Feeders Weather Volality Table 3. Rex Ranch Annual Calf Cost ($/head) The following events are based on a 201 Average true story. 1 2012 2013 2014 2015 Variao Calf Cost 453 635 876 591 579 n Variaon from previous year (20) 182 241 (285) (12) 148 BIF 2016 General Session II 1 Chip Ramsay, Rex Ranch June 16, 2016 Trust between Price Volality segments • Weighing condi5ons • Do what is best for the cale instead of worry • Streamline vaccinaon about who gets the Table 2. Percentage variaon in revenue per head from one year protocol advantage. to the next • Sharing in added value ??? 201 201 201 201 5 year Avg. $/ 2 3 4 5 2016 avg.d head e Jan-Mar 550 lb. Steer a 16% -2% 26% 28% -30% 20% $ -

Notes and Topics: Synopsis of Taranatha's History

SYNOPSIS OF TARANATHA'S HISTORY Synopsis of chapters I - XIII was published in Vol. V, NO.3. Diacritical marks are not used; a standard transcription is followed. MRT CHAPTER XIV Events of the time of Brahmana Rahula King Chandrapala was the ruler of Aparantaka. He gave offerings to the Chaityas and the Sangha. A friend of the king, Indradhruva wrote the Aindra-vyakarana. During the reign of Chandrapala, Acharya Brahmana Rahulabhadra came to Nalanda. He took ordination from Venerable Krishna and stu died the Sravakapitaka. Some state that he was ordained by Rahula prabha and that Krishna was his teacher. He learnt the Sutras and the Tantras of Mahayana and preached the Madhyamika doctrines. There were at that time eight Madhyamika teachers, viz., Bhadantas Rahula garbha, Ghanasa and others. The Tantras were divided into three sections, Kriya (rites and rituals), Charya (practices) and Yoga (medi tation). The Tantric texts were Guhyasamaja, Buddhasamayayoga and Mayajala. Bhadanta Srilabha of Kashmir was a Hinayaist and propagated the Sautrantika doctrines. At this time appeared in Saketa Bhikshu Maha virya and in Varanasi Vaibhashika Mahabhadanta Buddhadeva. There were four other Bhandanta Dharmatrata, Ghoshaka, Vasumitra and Bu dhadeva. This Dharmatrata should not be confused with the author of Udanavarga, Dharmatrata; similarly this Vasumitra with two other Vasumitras, one being thr author of the Sastra-prakarana and the other of the Samayabhedoparachanachakra. [Translated into English by J. Masuda in Asia Major 1] In the eastern countries Odivisa and Bengal appeared Mantrayana along with many Vidyadharas. One of them was Sri Saraha or Mahabrahmana Rahula Brahmachari. At that time were composed the Mahayana Sutras except the Satasahasrika Prajnaparamita. -

Mandukya Upanishad Class 6

Mandukya Upanishad Class 6 Mantra # 5: That is the state of deep sleep wherein the sleeper does not desire any objects nor does he see any dream. The third quarter (pada) is the “Prajna” whose sphere is deep sleep, in whom all (experiences) become unified or undifferentiated, who is verily a homogeneous mass of Consciousness entire, who is full of bliss, who is indeed an enjoyer of bliss and who is the very gateway for projection of consciousness into other two planes of Consciousness-the dream and the waking. Swamiji said the four padas are being explained from mantra # 3. First pada is the sthula atma where “I”, Chaitanyam, am connected with Sthula nama rupa. When I am connected with one sthula nama rupa I am vishwa sthula atma. When I am connected with samashti, I am called Samashti Sthula atma. In second pada or mantra the sukshma atma has both micro and macro aspects to it. Thus, I have Vyashti and samashti aspects in dream state. Vyashti is Taijasa and samashti is Hiranyagarbha. In the fifth mantra we have come to karana atma. Here I am in shushupti avastha associated with karana nama rupas, all in potential form. Individual nama rupa are called Pragya karana atma. All nama rupa’s in potential form are called anataryami karana atma. In jagrat and svapna avastha micro and macrocosm are visibly different while in sushupti I can’t differentiate between Vyashti and samashti; however, differences do exist. Pragya and anatharyami are physically visible but theoretically we should know that they are different. -

The Significance of Fire Offering in Hindu Society

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH ISSN : 2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR - 2.735; IC VALUE:5.16 VOLUME 3, ISSUE 7(3), JULY 2014 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF FIRE OFFERING IN HINDU THE SIGNIFICANCESOCIETY OF FIRE OFFERING IN HINDU SOCIETY S. Sushrutha H. R. Nagendra Swami Vivekananda Yoga Swami Vivekananda Yoga University University Bangalore, India Bangalore, India R. G. Bhat Swami Vivekananda Yoga University Bangalore, India Introduction Vedas demonstrate three domains of living for betterment of process and they include karma (action), dhyana (meditation) and jnana (knowledge). As long as individuality continues as human being, actions will follow and it will eventually lead to knowledge. According to the Dhatupatha the word yajna derives from yaj* in Sanskrit language that broadly means, [a] worship of GODs (natural forces), [b] synchronisation between various domains of creation and [c] charity.1 The concept of God differs from religion to religion. The ancient Hindu scriptures conceptualises Natural forces as GOD or Devatas (deva that which enlightens [div = light]). Commonly in all ancient civilizations the worship of Natural forces as GODs was prevalent. Therefore any form of manifested (Sun, fire and so on) and or unmanifested (Prana, Manas and so on) form of energy is considered as GOD even in Hindu tradition. Worship conceives the idea of requite to the sources of energy forms from where the energy is drawn for the use of all 260 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH ISSN : 2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR - 2.735; IC VALUE:5.16 VOLUME 3, ISSUE 7(3), JULY 2014 life forms. Worshiping the Gods (Upasana) can be in the form of worship of manifest forms, prostration, collection of ingredients or devotees for worship, invocation, study and discourse and meditation. -

An Understanding of Maya: the Philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva

An understanding of Maya: The philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva Department of Religion studies Theology University of Pretoria By: John Whitehead 12083802 Supervisor: Dr M Sukdaven 2019 Declaration Declaration of Plagiarism 1. I understand what plagiarism means and I am aware of the university’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this Dissertation is my own work. 3. I did not make use of another student’s previous work and I submit this as my own words. 4. I did not allow anyone to copy this work with the intention of presenting it as their own work. I, John Derrick Whitehead hereby declare that the following Dissertation is my own work and that I duly recognized and listed all sources for this study. Date: 3 December 2019 Student number: u12083802 __________________________ 2 Foreword I started my MTh and was unsure of a topic to cover. I knew that Hinduism was the religion I was interested in. Dr. Sukdaven suggested that I embark on the study of the concept of Maya. Although this concept provided a challenge for me and my faith, I wish to thank Dr. Sukdaven for giving me the opportunity to cover such a deep philosophical concept in Hinduism. This concept Maya is deeper than one expects and has broaden and enlightened my mind. Even though this was a difficult theme to cover it did however, give me a clearer understanding of how the world is seen in Hinduism. 3 List of Abbreviations AD Anno Domini BC Before Christ BCE Before Common Era BS Brahmasutra Upanishad BSB Brahmasutra Upanishad with commentary of Sankara BU Brhadaranyaka Upanishad with commentary of Sankara CE Common Era EW Emperical World GB Gitabhasya of Shankara GK Gaudapada Karikas Rg Rig Veda SBH Sribhasya of Ramanuja Svet. -

Types of Causes in Aristotle and Sankara

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Religious Studies Honors Theses Department of Religious Studies 9-11-2006 Types of Causes in Aristotle and Sankara Brandie Martinez-Bedard Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_hontheses Recommended Citation Martinez-Bedard, Brandie, "Types of Causes in Aristotle and Sankara." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_hontheses/3 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TYPES OF CAUSES IN ARISTOTLE AND SANKARA by BRANDIE MARTINEZ BEDARD Under the Direction of Kathryn McClymond and Sandra Dwyer ABSTRACT This paper is a comparative project between a philosopher from the Western tradition, Aristotle, and a philosopher from the Eastern tradition, Sankara. These two philosophers have often been thought to oppose one another in their thoughts, but I will argue that they are similar in several aspects. I will explore connections between Aristotle and Sankara, primarily in their theories of causation. I will argue that a closer examination of both Aristotelian and Advaita Vedanta philosophy, of which Sankara is considered the most prominent thinker, will yield significant similarities that will give new insights into the thoughts -

May I Answer That?

MAY I ANSWER THAT? By SRI SWAMI SIVANANDA SERVE, LOVE, GIVE, PURIFY, MEDITATE, REALIZE Sri Swami Sivananda So Says Founder of Sri Swami Sivananda The Divine Life Society A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION First Edition: 1992 Second Edition: 1994 (4,000 copies) World Wide Web (WWW) Reprint : 1997 WWW site: http://www.rsl.ukans.edu/~pkanagar/divine/ This WWW reprint is for free distribution © The Divine Life Trust Society ISBN 81-7502-104-1 Published By THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttar Pradesh, Himalayas, India. Publishers’ Note This book is a compilation from the various published works of the holy Master Sri Swami Sivananda, including some of his earliest works extending as far back as the late thirties. The questions and answers in the pages that follow deal with some of the commonest, but most vital, doubts raised by practising spiritual aspirants. What invests these answers and explanations with great value is the authority, not only of the sage’s intuition, but also of his personal experience. Swami Sivananda was a sage whose first concern, even first love, shall we say, was the spiritual seeker, the Yoga student. Sivananda lived to serve them; and this priceless volume is the outcome of that Seva Bhav of the great Master. We do hope that the aspirant world will benefit considerably from a careful perusal of the pages that follow and derive rare guidance and inspiration in their struggle for spiritual perfection. May the holy Master’s divine blessings be upon all. SHIVANANDANAGAR, JANUARY 1, 1993. -

FOUNDATIONS of SATYAGRAHA Dr Madhu Prashar Principal, Dev Samaj College for Women, Ferozepur City, Punjab

© 2014 JETIR August 2014, Volume 1, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) FOUNDATIONS OF SATYAGRAHA Dr Madhu Prashar Principal, Dev Samaj College for Women, Ferozepur City, Punjab. ABSTRACT The Gandhian technique of Satyagraha could be characterised by the term 'syncretic'. Although the impact of the west upon Indian traditions has elicited a response that is truly Indian, the end product bears non-mistakeable traces of the thought and experience of modern Europe. Efforts to revitalize Hinduism by creating a Hindu Raj and recover the glories of an idealized Hindu past were (and continue to be made by social and political groups and orthodox Hindu political parties. The importance of differentiating the Gandhian technique on the one hand, from the purely traditional on the other, cannot be over emphasised. As already mentioned, Gandhi used the traditional to promote the novel, reinterpreting tradition in such a way that revolutionary ideas, clothed in familiar expression, were readily adopted and employed towards revolutionary ends. In this research paper, it will be highlighted that how the two streams of thought merge and how Gandhi's leadership and creativeness transform elements from both developed the Satyagraha technique and can be understood better by analysing aspects of Hindu tradition in his background – the philosophical concept of Satya, the popular and ethical meaning of the Jain, Buddhist and Hindu ideal of Ahimsa, and concept of tapas (self-suffering) in Indian ethics will also be covered. INTRODUCTION: Gandhi has repeatedly acknowledged the influence of Western thinkers like Tolstoy, Ruskin, Thoreau the New Testament. In each case the influence was only of the nature of corroboration of an already accepted ethical precept, and a crystallization of basic predispositions. -

Chapter-N Cetasika (Mental Factors) 2.0. Introduction

44 Chapter-n Cetasika (Mental Factors) 2.0. Introduction In the first chapter, Citta (Consciousness) has been introduced. In this chapter, Cetasika (Mental factors) which means depending on citta will be discussed in detail with reference to the Abhidhamma pitaka by dividing topics and subtopics related to the present chapter. In the eighty-nine types of consciousness, enumerated in the first chapter, fifty-two mental factors arise in varying degree.There are seven concomitants common to every consciousness. There are six others that may or may not arise in each and every consciousness. They are termed Pakinnakas or Ethically variable factors. All these thirteen are designated Annasamanas, a rather peculiar technical term. Anna means other, samana means common. Sobhanas (Good), when compared with Asobhanas (Evil), are called Aiina (other) 'being of the opposite category'. Thus the Asobhanas are in contradistinction to Sobhanas. These thirteen become moral or immoral according to the types of consciousness in which they occur. 45 The fourteen concomitants are invariably found in every type of immoral consciousness. The nineteen are common to all type of moral consciousness. The six are moral concomitants which occur as occasion arises. Therefore these fifty-two (7+6+14+19+6=52) are found in all the types of consciousness in different proportions. In this chapter all the 52- mental factors are enumerated and classified. Every type of consciousness is microscopically analysed, and the accompanying psychic factors are given in details. The types of consciousness in which each mental factor occurs, is also described. 2.1. Definition of Cetasika Cetasika=cetas+ika When citta arises, it arises with mental factors that depend on it. -

The Upanishads- an Overview

The Upanishads- An overview (S.N.Sastri) The word ‘Upanishad’ denotes Brahma-vidya by its derivation. Sri Sankara Bhagavatpada says in his Bhashya on the Kathopanishad that this word is derived by adding the prefixes ‘upa’ (meaning near) and ‘ni’ (with certainty) to the root ‘sad’ which means ‘to destroy’, ‘to reach’, and ‘to loosen’. Thus the meaning of the word ‘Upanishad’ is that it is the knowledge that destroys the seeds of worldly existence such as ignorance in the case of those seekers of liberation who, after becoming free from all desires approach (upa sad) this knowledge. The subject-matter of the upanishads is Brahman, the only Reality. Brihadaaranyaka upanishad, 3. 9. 26 says, “I ask you about Him, the Purusha of the upanishads”. The upanishads are the only source of knowledge about Brahman. The method adopted in Vedanta to impart the knowledge of Brahman is known as the method of superimposition ( adhyaaropa ) and subsequent negation ( apavaada ). In the Bhashya on Br.up.4.4.25 Bhagavatpada says, “The transmigrating self is indeed Brahman. He who knows the self as Brahman which is beyond fear becomes Brahman. This is the purport of the whole upanishad put in a nutshell. It is to bring out this purport that the ideas of creation, maintenance and dissolution of the universe, as well as the ideas of action, its factors and results were superimposed on the Self. Then, by the negation of the superimposed attributes the true nature of Brahman as free from all attributes has been brought out”. This is the method of adhyaaropa and apavaada, superimposition and negation, which is adopted by Vedanta. -

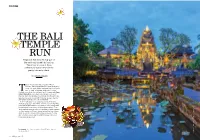

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

Cūḷa Sīha,Nāda Sutta

M 1.1.1 Majjhima Nikya 1, Mūla Paṇṇāsa 1, Sīha,nāda Vagga 1 2 Cūḷa Sīha,nāda Sutta The Lesser Discourse on the Lion-roar | M 11 Theme: Witnessing the true teaching and Buddhist missiology Translated & annotated by Piya Tan ©2015 0 The Cūḷa Sīha,nāda Sutta: summary and highlights 0.1 THE LION-ROAR 0.1.1 What is a lion-roar? 0.1.1.1 The Cūḷa Sīha,nāda Sutta opens with the Buddha encouraging us to make a lion-roar, a public witness of faith that the true liberated saints (the arhats) are found only in the Buddha’s teaching [5.1.1]. The imagery of the lion-roar is based on the well known nature of the lion, as described here, in the (Anicca) Sīha Sutta (A 2.10): 3 “The lion, bhikshus, king of the beasts, in the evening emerges from his lair. Having emerg- ed, he stretches himself, surveys the four quarters all around, roars his lion-roar thrice, and then leaves for his hunting-ground. [85] 4 Bhikshus, when the animals and creatures hear the roar of the lion, the king of the beasts, they, for the most part, are struck with fear, urgency1 and trembling.2 Those that live in holes, enter their holes; the water-dwellers head into the waters; the forest- dwellers, seek the forests; winged birds resort to the skies.3 5 Bhikshus, those royal elephants bound by stout bonds, in the villages, market towns and capitals—they break and burst their bonds, and flee about in terror, voiding and peeing.