Does Macroeconomics Need Microeconomic Foundations?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Principles of MICROECONOMICS an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine

with Open Texts Principles of MICROECONOMICS an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine VERSION 2017 – REVISION B ADAPTABLE | ACCESSIBLE | AFFORDABLE Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-SA) advancing learning Champions of Access to Knowledge OPEN TEXT ONLINE ASSESSMENT All digital forms of access to our high- We have been developing superior on- quality open texts are entirely FREE! All line formative assessment for more than content is reviewed for excellence and is 15 years. Our questions are continuously wholly adaptable; custom editions are pro- adapted with the content and reviewed for duced by Lyryx for those adopting Lyryx as- quality and sound pedagogy. To enhance sessment. Access to the original source files learning, students receive immediate per- is also open to anyone! sonalized feedback. Student grade reports and performance statistics are also provided. SUPPORT INSTRUCTOR SUPPLEMENTS Access to our in-house support team is avail- Additional instructor resources are also able 7 days/week to provide prompt resolu- freely accessible. Product dependent, these tion to both student and instructor inquiries. supplements include: full sets of adaptable In addition, we work one-on-one with in- slides and lecture notes, solutions manuals, structors to provide a comprehensive sys- and multiple choice question banks with an tem, customized for their course. This can exam building tool. include adapting the text, managing multi- ple sections, and more! Contact Lyryx Today! [email protected] advancing learning Principles of Microeconomics an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine Version 2017 — Revision B BE A CHAMPION OF OER! Contribute suggestions for improvements, new content, or errata: A new topic A new example An interesting new question Any other suggestions to improve the material Contact Lyryx at [email protected] with your ideas. -

The Lucas Critique – Is It Really Relevant?

Working Paper Series Department of Business & Management Macroeconomic Methodology, Theory and Economic Policy (MaMTEP) No. 7, 2016 The Lucas Critique – is it really relevant? By Finn Olesen 1 Abstract: As one of the founding fathers of what became the modern macroeconomic mainstream, Robert E. Lucas has made several important contributions. In the present paper, the focus is especially on his famous ‘Lucas critique’, which had tremendous influence on how to build macroeconomic models and how to evaluate economic policies within the modern macroeconomic mainstream tradition. However, much of this critique should not come as a total surprise to Post Keynesians as Keynes himself actually discussed many of the elements present in Lucas’s 1976 article. JEL classification: B22, B31 & E20 Key words: Lucas, microfoundations for macroeconomics, realism & Post Keynesianism I have benefitted from useful comments from Robert Ayreton Bailey Smith and Peter Skott. 2 Introduction In 1976, Robert Lucas published a contribution that since has had an enormous impact on modern macroeconomics. Based on the Lucas critique, the search for an explicit microfoundation for macroeconomic theory began in earnest. Later on, consensus regarding methodological matters between the New Classical and the New Keynesian macroeconomists emerged. That is, it was accepted that macroeconomics could only be done within an equilibrium framework with intertemporal optimising households and firms using rational expectations. As such, the representative agent was born. Accepting such a framework has of course not only theoretical consequences but also methodological ones as for instance pointed out by McCombie & Pike (2013). Not only should macroeconomics rest upon explicit and antiquated, although accepted, microeconomic axioms; macroeconomic theory also had to be formulated exclusively by use of mathematical modelling1. -

Microeconomics III Oligopoly — Preface to Game Theory

Microeconomics III Oligopoly — prefacetogametheory (Mar 11, 2012) School of Economics The Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Herzliya Oligopoly is a market in which only a few firms compete with one another, • and entry of new firmsisimpeded. The situation is known as the Cournot model after Antoine Augustin • Cournot, a French economist, philosopher and mathematician (1801-1877). In the basic example, a single good is produced by two firms (the industry • is a “duopoly”). Cournot’s oligopoly model (1838) — A single good is produced by two firms (the industry is a “duopoly”). — The cost for firm =1 2 for producing units of the good is given by (“unit cost” is constant equal to 0). — If the firms’ total output is = 1 + 2 then the market price is = − if and zero otherwise (linear inverse demand function). We ≥ also assume that . The inverse demand function P A P=A-Q A Q To find the Nash equilibria of the Cournot’s game, we can use the proce- dures based on the firms’ best response functions. But first we need the firms payoffs(profits): 1 = 1 11 − =( )1 11 − − =( 1 2)1 11 − − − =( 1 2 1)1 − − − and similarly, 2 =( 1 2 2)2 − − − Firm 1’s profit as a function of its output (given firm 2’s output) Profit 1 q'2 q2 q2 A c q A c q' Output 1 1 2 1 2 2 2 To find firm 1’s best response to any given output 2 of firm 2, we need to study firm 1’s profit as a function of its output 1 for given values of 2. -

ECON - Economics ECON - Economics

ECON - Economics ECON - Economics Global Citizenship Program ECON 3020 Intermediate Microeconomics (3) Knowledge Areas (....) This course covers advanced theory and applications in microeconomics. Topics include utility theory, consumer and ARTS Arts Appreciation firm choice, optimization, goods and services markets, resource GLBL Global Understanding markets, strategic behavior, and market equilibrium. Prerequisite: ECON 2000 and ECON 3000. PNW Physical & Natural World ECON 3030 Intermediate Macroeconomics (3) QL Quantitative Literacy This course covers advanced theory and applications in ROC Roots of Cultures macroeconomics. Topics include growth, determination of income, employment and output, aggregate demand and supply, the SSHB Social Systems & Human business cycle, monetary and fiscal policies, and international Behavior macroeconomic modeling. Prerequisite: ECON 2000 and ECON 3000. Global Citizenship Program ECON 3100 Issues in Economics (3) Skill Areas (....) Analyzes current economic issues in terms of historical CRI Critical Thinking background, present status, and possible solutions. May be repeated for credit if content differs. Prerequisite: ECON 2000. ETH Ethical Reasoning INTC Intercultural Competence ECON 3150 Digital Economy (3) Course Descriptions The digital economy has generated the creation of a large range OCOM Oral Communication of significant dedicated businesses. But, it has also forced WCOM Written Communication traditional businesses to revise their own approach and their own value chains. The pervasiveness can be observable in ** Course fulfills two skill areas commerce, marketing, distribution and sales, but also in supply logistics, energy management, finance and human resources. This class introduces the main actors, the ecosystem in which they operate, the new rules of this game, the impacts on existing ECON 2000 Survey of Economics (3) structures and the required expertise in those areas. -

5. the Lucas Critique and Monetary Policy

5. The Lucas Critique and Monetary Policy John B. Taylor, May 6, 2013 Econometric Policy Evaluation: A Critique • Highly influential (Nobel Prize) • Adds to the case for policy rules • Shows difficulties of econometric policy evaluation when forward-looking expectations are introduced • But it left an impression of a “mission impossible” for monetary economists – Tended to draw researchers away from monetary policy research to real business cycle models • Nevertheless it was constructive – An alternative approach suggested through three examples: • One focussed on monetary policy – inflation-unemployment tradeoff • The other two focused on fiscal policy – consumption and investment • Worth studying in the original First Derive the Inflation-Output Tradeoff Derive "aggregate supply" function : Supply yit in market i at time t is given by P c yit yit yit where P yit is "permanent" or "normal" supply c yit is "cyclical" supply Supply curve in market i c e yit ( pit pit ) pit is the log of the actual price in market i at time t e pit is the perceived (in market i) general price level in the economy at time t Find conditional expectation of general price level pit pt zit 2 pt is distributed normally with mean ptand variance 2 zit is distributed normally with mean 0 and variance Thus 2 2 pt p is distributed N t p 2 2 2 it pt e 2 2 2 pit E( pt pit , I t1 ) pt [ /( )]( pit pt ) (1 ) pit pt where 2 /( 2 2 ) Covariance divided by the variance Now, substitute the conditional expectation e pit (1 ) pit -

FALL 2021 COURSE SCHEDULE August 23 –– December 9, 2021

9/15/21 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS FALL 2021 COURSE SCHEDULE August 23 –– December 9, 2021 Course # Class # Units Course Title Day Time Location Instruction Mode Instructor Limit 1078-001 20457 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 MWF 8:00-8:50 ECON 117 IN PERSON Bentz 47 1078-002 20200 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 MWF 6:30-7:20 ECON 119 IN PERSON Hurt 47 1078-004 13409 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Marein 71 1088-001 18745 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 2 MWF 6:30-7:20 HLMS 141 IN PERSON Zhou, S 47 1088-002 20748 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 2 MWF 8:00-8:50 HLMS 211 IN PERSON Flynn 47 2010-100 19679 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Keller 500 2010-200 14353 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Carballo 500 2010-300 14354 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Bottan 500 2010-600 14355 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Klein 200 2010-700 19138 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Gruber 200 2020-100 14356 4 Principles of Macroeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Valkovci 400 3070-010 13420 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory MWF 9:10-10:00 ECON 119 IN PERSON Barham 47 3070-020 21070 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory TTH 2:20-3:35 ECON 117 IN PERSON Chen 47 3070-030 20758 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory TTH 11:10-12:25 ECON 119 IN PERSON Choi 47 3070-040 21443 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory MWF 1:50-2:40 ECON 119 IN PERSON Bottan 47 3080-001 22180 3 Intermediate Macroeconomic Theory MWF 11:30-12:20 -

The Econometrics of the Lucas Critique: Estimation and Testing of Euler Equation Models with Time-Varying Reduced-Form Coefficients

The Econometrics of the Lucas Critique: Estimation and Testing of Euler Equation Models with Time-varying Reduced-form Coefficients Hong Li ∗y Princeton University Abstract The Lucas (1976) critique argued that the parameters of the traditional unrestricted macroeconometric models were unlikely to remain invariant in a changing economic envi- ronment. Since then, rational expectations models have become a fixture in macroeconomics Euler equations in particular. An important, though little acknowledged, implication of − the Lucas critique is that testing stability across regimes should be a natural diagnostic for the reliability of Euler equations. This paper formalizes this assertion econometrically in the framework of the classical two-step minimum distance method: The time-varying reduced- form in the first step reflects private agents' adaptation of their forecasts and behavior to the changing environment; The presumed ability of Euler conditions to deliver stable parame- ters that index tastes and technology is interpreted as a time-invariant second-step model. Within this framework, I am able to show, complementary to and independent of one an- other, both standard specification tests and stability tests are required for the evaluation of Euler equations. Moreover, this conclusion is shown to extend to other major estimation methods. Following this result, three standard investment Euler equations are submitted to examination. The empirical results tend to suggest that the standard models have not, thus far, been a success, at least for aggregate investment. JEL Classification: C13; C52; E22. Keywords: Parameter instability; Model validation testing; Classical minimum dis- tance estimation; The Lucas critique; Euler equations; Aggregate investment. ∗Department of Economics, Princeton University, NJ 08544. -

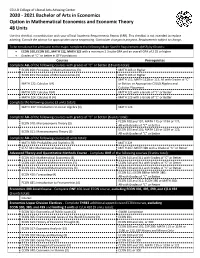

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

The Neoclassical Synthesis

Department of Economics- FEA/USP In Search of Lost Time: The Neoclassical Synthesis MICHEL DE VROEY PEDRO GARCIA DUARTE WORKING PAPER SERIES Nº 2012-07 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS, FEA-USP WORKING PAPER Nº 2012-07 In Search of Lost Time: The Neoclassical Synthesis Michel De Vroey ([email protected]) Pedro Garcia Duarte ([email protected]) Abstract: Present day macroeconomics has been sometimes dubbed as the new neoclassical synthesis, suggesting that it constitutes a reincarnation of the neoclassical synthesis of the 1950s. This has prompted us to examine the contents of the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ neoclassical syntheses. Our main conclusion is that the latter bears little resemblance with the former. Additionally, we make three points: (a) from its origins with Paul Samuelson onward the neoclassical synthesis notion had no fixed content and we bring out four main distinct meanings; (b) its most cogent interpretation, defended e.g. by Solow and Mankiw, is a plea for a pluralistic macroeconomics, wherein short-period market non-clearing models would live side by side with long-period market-clearing models; (c) a distinction should be drawn between first and second generation new Keynesian economists as the former defend the old neoclassical synthesis while the latter, with their DSGE models, adhere to the Lucasian view that macroeconomics should be based on a single baseline model. Keywords: neoclassical synthesis; new neoclassical synthesis; DSGE models; Paul Samuelson; Robert Lucas JEL Codes: B22; B30; E12; E13 1 IN SEARCH OF LOST TIME: THE NEOCLASSICAL SYNTHESIS Michel De Vroey1 and Pedro Garcia Duarte2 Introduction Since its inception, macroeconomics has witnessed an alternation between phases of consensus and dissent. -

Reconstructing the Great Recession

Reconstructing the Great Recession Michele Boldrin, Carlos Garriga, Adrian Peralta-Alva, and Juan M. Sánchez This article uses dynamic equilibrium input-output models to evaluate the contribution of the con- struction sector to the Great Recession and the expansion preceding it. Through production inter- linkages and demand complementarities, shifts in housing demand can propagate to other economic sectors and generate a large and sustained aggregate cycle. According to our model, the housing boom (2002-07) fueled more than 60 percent and 25 percent of employment and GDP growth, respectively. The decline in the construction sector (2007-10) generates a drop in total employment and output about half of that observed in the data. In sharp contrast, ignoring interlinkages or demand comple- mentarities eliminates the contribution of the construction sector. (JEL E22, E32, O41) Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, Third Quarter 2020, 102(3), pp. 271-311. https://doi.org/10.20955/r.102.271-311 1 INTRODUCTION With the onset of the Great Recession, U.S. employment and gross domestic product (GDP) fell dramatically and then took a long time to return to their historical trends. There is still no consensus about what exactly made the recession so deep and the subsequent recovery so slow. In this article we evaluate the role played by the construction sector in driving the boom and bust of the U.S. economy during 2001-13. The construction sector represents around 5 percent of total employment, and its share of GDP is about 4.5 percent. Mechanically, the macroeconomic impact of a shock to the con- struction sector should be limited by these figures; we claim it is not. -

The Lucas Critique and the Stability of Empirical Models∗

Working Paper Series This paper can be downloaded without charge from: http://www.richmondfed.org/publications/ The Lucas Critique and the Stability of Empirical Models∗ Thomas A. Lubik Paolo Surico Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Bank of England and University of Bari July 2006 Working Paper No. 06-05 Abstract This paper re-considers the empirical relevance of the Lucas critique using a DSGE sticky price model in which a weak central bank response to inflation generates equilib- rium indeterminacy. The model is calibrated on the magnitude of the historical shift in the Federal Reserve’s policy rule and is capable of generating the decline in the volatility of inflation and real activity observed in U.S. data. Using Monte Carlo simulations and a backward-looking model of aggregate supply and demand, we show that shifts in the policy rule induce breaks in both the reduced-form coefficients and the reduced-form error variances. The statistics of popular parameter stability tests are shown to have low power if such heteroskedasticity is neglected. In contrast, when the instability of the reduced-form error variances is accounted for, the Lucas critique is found to be empirically relevant for both artificial and actual data. JEL Classification: C52, E38, E52. Key Words: Lucas critique, heteroskedasticity, parameter stability tests, rational expectations, indeterminacy. ∗WearegratefultoLucaBenati,AndrewBlake,Jon Faust, Jan Groen, Haroon Mumtaz, Serena Ng, Christoph Schleicher, Frank Schorfheide, Shaun Vahey and seminar participants at the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the Bank of England, the 2006 meeting of the Society of Computational Economics, the con- ference on “Macroeconometrics and Model Uncertainty” held on 27-28 June 2006 at the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, and our discussant Timothy Kam for valuable comments and suggestions. -

The History of Macroeconomics from Keynes's General Theory to The

The History of Macroeconomics from Keynes’s General Theory to the Present M. De Vroey and P. Malgrange Discussion Paper 2011-28 The History of Macroeconomics from Keynes’s General Theory to the Present Michel De Vroey and Pierre Malgrange ◊ June 2011 Abstract This paper is a contribution to the forthcoming Edward Elgar Handbook of the History of Economic Analysis volume edited by Gilbert Faccarello and Heinz Kurz. Its aim is to introduce the reader to the main episodes that have marked the course of modern macroeconomics: its emergence after the publication of Keynes’s General Theory, the heydays of Keynesian macroeconomics based on the IS-LM model, disequilibrium and non-Walrasian equilibrium modelling, the invention of the natural rate of unemployment notion, the new classical attack against Keynesian macroeconomics, the first wave of new Keynesian models, real business cycle modelling and, finally, the second wage of new Keynesian models, i.e. DSGE models. A main thrust of the paper is the contrast we draw between Keynesian macroeconomics and stochastic dynamic general equilibrium macroeconomics. We hope that our paper will be useful for teachers of macroeconomics wishing to complement their technical material with a historical addendum. Keywords: Keynes, Lucas, IS-LM model, DSGE models JEL classification: B 22, E 10, E 20, E 30 ◊ IRES, Louvain University and CEPREMAP, Paris. Correspondence address : [email protected] The authors are grateful to Liam Graham for his comments on an earlier version of the paper. 1 Introduction Our aim in this paper is to introduce the reader to the main episodes that have marked the course of macroeconomics.