Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds of Gunung Tambora, Sumbawa, Indonesia: Effects of Altitude, the 1815 Cataclysmic Volcanic Eruption and Trade

FORKTAIL 18 (2002): 49–61 Birds of Gunung Tambora, Sumbawa, Indonesia: effects of altitude, the 1815 cataclysmic volcanic eruption and trade COLIN R. TRAINOR In June-July 2000, a 10-day avifaunal survey on Gunung Tambora (2,850 m, site of the greatest volcanic eruption in recorded history), revealed an extraordinary mountain with a rather ordinary Sumbawan avifauna: low in total species number, with all species except two oriental montane specialists (Sunda Bush Warbler Cettia vulcania and Lesser Shortwing Brachypteryx leucophrys) occurring widely elsewhere on Sumbawa. Only 11 of 19 restricted-range bird species known for Sumbawa were recorded, with several exceptional absences speculated to result from the eruption. These included: Flores Green Pigeon Treron floris, Russet-capped Tesia Tesia everetti, Bare-throated Whistler Pachycephala nudigula, Flame-breasted Sunbird Nectarinia solaris, Yellow-browed White- eye Lophozosterops superciliaris and Scaly-crowned Honeyeater Lichmera lombokia. All 11 resticted- range species occurred at 1,200-1,600 m, and ten were found above 1,600 m, highlighting the conservation significance of hill and montane habitat. Populations of the Yellow-crested Cockatoo Cacatua sulphurea, Hill Myna Gracula religiosa, Chestnut-backed Thrush Zoothera dohertyi and Chestnut-capped Thrush Zoothera interpres have been greatly reduced by bird trade and hunting in the Tambora Important Bird Area, as has occurred through much of Nusa Tenggara. ‘in its fury, the eruption spared, of the inhabitants, not a although in other places some vegetation had re- single person, of the fauna, not a worm, of the flora, not a established (Vetter 1820 quoted in de Jong Boers 1995). blade of grass’ Francis (1831) in de Jong Boers (1995), Nine years after the eruption the former kingdoms of referring to the 1815 Tambora eruption. -

FORUM MASYARAKAT ADAT DATARAN TINGGI BORNEO (FORMADAT) Borneo (Indonesia & Malaysia)

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. FORUM MASYARAKAT ADAT DATARAN TINGGI BORNEO (FORMADAT) Borneo (Indonesia & Malaysia) Equator Initiative Case Studies Local sustainable development solutions for people, nature, and resilient communities UNDP EQUATOR INITIATIVE CASE STUDY SERIES Local and indigenous communities across the world are 126 countries, the winners were recognized for their advancing innovative sustainable development solutions achievements at a prize ceremony held in conjunction that work for people and for nature. Few publications with the United Nations Convention on Climate Change or case studies tell the full story of how such initiatives (COP21) in Paris. Special emphasis was placed on the evolve, the breadth of their impacts, or how they change protection, restoration, and sustainable management over time. Fewer still have undertaken to tell these stories of forests; securing and protecting rights to communal with community practitioners themselves guiding the lands, territories, and natural resources; community- narrative. The Equator Initiative aims to fill that gap. based adaptation to climate change; and activism for The Equator Initiative, supported by generous funding environmental justice. The following case study is one in from the Government of Norway, awarded the Equator a growing series that describes vetted and peer-reviewed Prize 2015 to 21 outstanding local community and best practices intended to inspire the policy dialogue indigenous peoples initiatives to reduce poverty, protect needed to take local success to scale, to improve the global nature, and strengthen resilience in the face of climate knowledge base on local environment and development change. Selected from 1,461 nominations from across solutions, and to serve as models for replication. -

Indonesia's Transformation and the Stability of Southeast Asia

INDONESIA’S TRANSFORMATION and the Stability of Southeast Asia Angel Rabasa • Peter Chalk Prepared for the United States Air Force Approved for public release; distribution unlimited ProjectR AIR FORCE The research reported here was sponsored by the United States Air Force under Contract F49642-01-C-0003. Further information may be obtained from the Strategic Planning Division, Directorate of Plans, Hq USAF. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rabasa, Angel. Indonesia’s transformation and the stability of Southeast Asia / Angel Rabasa, Peter Chalk. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. “MR-1344.” ISBN 0-8330-3006-X 1. National security—Indonesia. 2. Indonesia—Strategic aspects. 3. Indonesia— Politics and government—1998– 4. Asia, Southeastern—Strategic aspects. 5. National security—Asia, Southeastern. I. Chalk, Peter. II. Title. UA853.I5 R33 2001 959.804—dc21 2001031904 Cover Photograph: Moslem Indonesians shout “Allahu Akbar” (God is Great) as they demonstrate in front of the National Commission of Human Rights in Jakarta, 10 January 2000. Courtesy of AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE (AFP) PHOTO/Dimas. RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND® is a registered trademark. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. Cover design by Maritta Tapanainen © Copyright 2001 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, -

Tbi Kalimantan 6.Pdf

Forest Products and Local Forest Management in West Kalimantan, Indonesia: Implications for Conservation and Development ISBN 90-5113-056-2 ISSN 1383-6811 © 2002 Tropenbos International The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Tropenbos International No part of this publication, apart from bibliographic data and brief quotations in critical reviews, may be reproduced, re-recorded or published in any form including print photocopy, microform, electronic or electromagnetic record without written permission. Cover photo (inset) : Dayaks in East Kalimantan (Wil de Jong) Printed by : Ponsen en Looijen BV, Wageningen, the Netherlands FOREST PRODUCTS AND LOCAL FOREST MANAGEMENT IN WEST KALIMANTAN, INDONESIA: IMPLICATIONS FOR CONSERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT Wil de Jong Tropenbos International Wageningen, the Netherlands 2002 Tropenbos Kalimantan Series The Tropenbos Kalimantan Series present the results of studies and research activities related to sustainable use and conservation of forest resources in Indonesia. The multi-disciplinary MOF-Tropenbos Kalimantan Programme operates within the framework of Tropenbos International. Executing Indonesian agency is the Forestry Research Institute Samarinda (FRIS), governed by the Forestry Research and Development Agency (FORDA) of the Ministry of Forestry (MOF) Tropenbos International Wageningen The Netherlands Ministry of Forestry Indonesia Centre for International Forest Research Bogor Indonesia ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The field research that lead to this volume was funded by Tropenbos International and by the Rainforest Alliance through their Kleinhans Fellowship. While conducting the fieldwork, between 1992 and 1995, the author was a Research Associate at the New York Botanical Garden’s Institute for Economic Botany. The research was made possible through the Tanjungpura University, Pontianak, and the Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia. -

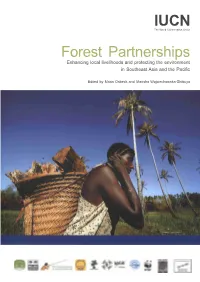

Forest Partnerships Enhancing Local Livelihoods and Protecting the Environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific

IUCN The World Conservation Union Forest Partnerships Enhancing local livelihoods and protecting the environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Edited by Maria Osbeck and Marisha Wojciechowska-Shibuya IUCN The World Conservation Union The designation of geographical entities in this report, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by: The World Conservation Union (IUCN), Asia Regional Office Copyright: © 2007 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Osbeck, M., Wojciechowska-Shibuya, M. (Eds) (2007). Forest Partnerships. Enhancing local livelihoods and protecting the environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. IUCN, Bangkok, Thailand. 48pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1011-2 Cover design by: IUCN Asia Regional Office Cover photos: Local people, Papua New Guinea. A woman transports a basketful of baked sago from a pit oven back to Rhoku village. Sago is a common subsistence crop in Papua New Guinea. Western Province, Papua New Guinea. December 2004 CREDIT: © Brent Stirton / Getty Images / WWF-UK Layout by: Michael Dougherty Produced by: IUCN Asia Regional Office Printed by: Clung Wicha Press Co., Ltd. -

Experience from Indonesia on the Rabies Introduction Emergency

Ministry Of Agriculture Directorat General of Livestock and Animal Health Bangkok, 27 August 2019 http://ditjennak.pertanian.go.id/ Email : [email protected] Data Sampai tanggal 19 Januari 2019 • Ministry Of Agriculture (MoA) • Ministry Of Public Health (MoH) • Laboratory Denpasar (DIC Denpasar) • Departemen of Husbandary NTB Province • Departemen of Public Health A dog used as guardian of gardens ~ • Dogs use for hunting • Animal movement • The entry of a dog that accompanies traditional fishers Jalur Flores (Labuan Bajo)-Sumbawa (Dompu) Many Iegal Port without Quarantine Jalur Bali (Padang Bai)-Sumbawa (Dompu) Number of Population Rabies animal is known Information about Threat and Rabies Danger isnt known The owner of Animal isn’t responsible Vaccination Movement Dog from Endemis area , to Sumbawa Island, example from Bali and NTT Elimination which animal welfare • Training for vaccinator and Dog catcher →60 officers (Dompu, sumbawa, Bima dan Propinsi) • Training for Laboratory, → 15 officer Capacity • Training for disease investigation Building • The dog population training → 30 officer Human Resouces • Distribution vaccine and operational for vaccination • Dompu Vaccine & • Sumbawa Operasional • Bima •Est.pop: 10,334 •R.Vaccination: 6.165 Dompu •Doses of Vaccines: 9.000 •Human Resources: 40 persons •Est.pop: 36,671 Sumba •R.Vaccination: 2.210 •Doses of vaccine: 3.000 wa •Human Resources: 12 persons •Est.pop:16.100 •R.Vaccination: 1.503 Bima •Doses of Vaksin: 2000 •SDM :10 petugas Socialization for Community, figure public -

National Report on Animal Genetic Resources Indonesia

NATIONAL REPORT ON ANIMAL GENETIC RESOURCES INDONESIA A Strategic Policy Document F O R E W O R D The Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Indonesia, represented by the Directorate General of Livestock Services, has been invited by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to participate in the preparation of the first State of The World’s Animal Genetic Resources. The State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources is important, and has to be supported by all institutions concerned, by the experts, by the politicians, by the breeders, by the farmers and farmer’s societies and by other stakeholders in the country. The World Food Summit in 1996 committed to reducing the number of people who are suffering from malnutrition in the world from 800 million to 400 million by the year 2015. This will have a tremendous implication for Indonesia which has human population growth of almost 3 million people a year. Indonesia has a large biodiversity which could be utilized to increase and strengthen national food security. Indonesia has lots of indigenous plant genetic resources and indigenous animal genetic resources consisting of mammals, reptiles and amphibians, birds and fish including species and breeds of farm genetic resources such as cattle, buffaloes, goats, sheep, pigs, chicken, ducks, horses and others. The objectives of agricultural development in Indonesia are principally increasing the farmer’s income and welfare, leading to National Food Security as well as the Development of Security as a Nation. The policies of management of animal genetic resources refers to three approaches, those are (1): Pure-breeding and Conservation; (2) Cross breeding; and (3) the Development of new breeds. -

1 a Study of Wetu Telu Syncretism in Lombok

SOSHUM: JURNAL SOSIAL DAN HUMANIORA Volume 8, Number 1, March 2018 p-ISSN. 2088-2262 e-ISSN. 2580-5622 A STUDY OF WETU TELU SYNCRETISM IN LOMBOK: A SOCIO-RELIGIOUS APPROACH I Wayan Wirata Sekolah Tinggi Agama Hindu Negeri Gde Pudja Mataram Address: Jl. Pancaka, No. 7B Mataram, Lombok Barat, Nusa Tenggara Barat, Indonesia Phone: +62 370 628382 Fax. +62 370 631725 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Wetu Telu is a syncretism of belief prevalent in West Lombok region. Danghyang Dwijendra from Daha in East Java region is regarded as the founder of the Watu Telu cult. He came to the Island of Lombok to teach enlightenment. One of the Ashram where he developed Hindu teaching and religion was Suranadi, a beautiful holy place. That Ashram was encircled by holy water, which currently can still be used by the Hindu devotees in performing their sacred sacrifice (yajnya). This study is aimed at knowing social and religious aspects of Wetu Telu as cultural heritage. The data is obtained through literature review and in-depth interview with public figures. From the data analysis, it is obtained that the history and social background of the Sasak people who inhab- it the island is a mix of ethnic groups and culture. With this background, Wetu Telu which is also the syncretism of Hindu, Buddha, Islam, and local culture has a composite nature by taking only important matters without leaving its original teaching. Wetu Telu is considered to be Lombok Hindu teaching; and Wetu Telu is as inseparable part of holy pilgrimage (dharma yatra) of Danghyang Nirartha to Lombok in giving enlightenment and spiritual happiness to the people of Lombok. -

“Great Is Our Relationship with the Sea1” Charting the Maritime Realm of the Sama of Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia

Lance Nolde “Great is Our Relationship with the Sea1” Charting the Maritime Realm of the Sama of Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia LANCE NOLDE University of Hawai!i AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY Lance Nolde is a Ph.D. student in History at the University of Hawai’i whose research interests include the histories of modern Indonesia, especially the histories and cultures of maritime communities in the eastern archipelago. Nolde is currently researching the histories of the Sama of eastern Indonesia during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Dispersed widely across the eastern seas of island group is composed of a number of smaller subgroups, Southeast Asia, Sama2 peoples have long caught the each with a slightly different dialect and cultural attention of visitors to the region. Whether in the attributes, and each possessing an intimate knowledge Southern Philippines, northern and eastern Borneo, or of a particular littoral environment in which they live as the numerous islands of eastern Indonesia, the unique well as a more general but still thorough knowledge of sea-centered lifestyle of the Sama has inspired many the broader maritime spaces in which they travel. observers to characterize them as “sea gypsies” or “sea Through lifetimes of carefully calculated long-distance nomads,” a people supposedly so adverse to dry land journeys as well as daily interaction with and movement that they “get sick if they stay on land even for a couple throughout a particular seascape, Sama peoples have of hours.”3 Living almost entirely in their boats and developed a deep familiarity with vast expanses of the sailing great distances in order to fish, forage, and eastern seas of island Southeast Asia and have transport valuable sea products, Sama peoples were, established far-ranging networks that criss-cross and and often still are, depicted as a sort of “curious connect those maritime spaces. -

Evidence of Unknown Paleo-Tsunami Events Along the Alas Strait, West Sumbawa, Indonesia

geosciences Article Evidence of Unknown Paleo-Tsunami Events along the Alas Strait, West Sumbawa, Indonesia Bachtiar W. Mutaqin 1,2,* , Franck Lavigne 2,* , Patrick Wassmer 2,3, Martine Trautmann 3 , Puncak Joyontono 1 , Christopher Gomez 4 , Bagus Septiangga 5, Jean-Christophe Komorowski 6, Junun Sartohadi 7 and Danang Sri Hadmoko 1 1 Coastal and Watershed Research Group, Faculty of Geography, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta 55281, Indonesia; [email protected] (P.J.); [email protected] (D.S.H.) 2 Laboratoire de Géographie Physique, Université Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne, 75231 Paris, France; [email protected] 3 Faculté de Géographie et d’Aménagement, Université de Strasbourg, 67000 Strasbourg, France; [email protected] 4 Department of Maritime Sciences, Graduate School of Maritime Sciences, Kobe University, Kobe, Hyogo 657-8501, Japan; [email protected] 5 Directorate General of Water Resources, Ministry of Public Works and Housing, Jakarta 12110, Indonesia; [email protected] 6 Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris UMR 7154, Université Sorbonne Paris Cité, 75005 Paris, France; [email protected] 7 Faculty of Agriculture, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta 55281, Indonesia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (B.W.M.); [email protected] (F.L.) Abstract: Indonesia is exposed to earthquakes, volcanic activities, and associated tsunamis. This is particularly the case for Lombok and Sumbawa Islands in West Nusa Tenggara, where evidence of Citation: Mutaqin, B.W.; Lavigne, F.; tsunamis is frequently observed in its coastal sedimentary record. If the 1815 CE Tambora eruption Wassmer, P.; Trautmann, M.; on Sumbawa Island generated a tsunami with well-identified traces on the surrounding islands, little Joyontono, P.; Gomez, C.; Septiangga, is known about the consequences of the 1257 CE tremendous eruption of Samalas on the neighboring B.; Komorowski, J.-C.; Sartohadi, J.; islands, and especially about the possible tsunamis generated in reason of a paucity of research on Hadmoko, D.S. -

Australia and Indonesia Current Problems, Future Prospects Jamie Mackie Lowy Institute Paper 19

Lowy Institute Paper 19 Australia and Indonesia CURRENT PROBLEMS, FUTURE PROSPECTS Jamie Mackie Lowy Institute Paper 19 Australia and Indonesia CURRENT PROBLEMS, FUTURE PROSPECTS Jamie Mackie First published for Lowy Institute for International Policy 2007 PO Box 102 Double Bay New South Wales 2028 Australia www.longmedia.com.au [email protected] Tel. (+61 2) 9362 8441 Lowy Institute for International Policy © 2007 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part Jamie Mackie was one of the first wave of Australians of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (including but not limited to electronic, to work in Indonesia during the 1950s. He was employed mechanical, photocopying, or recording), without the prior written permission of the as an economist in the State Planning Bureau under copyright owner. the auspices of the Colombo Plan. Since then he has been involved in teaching and learning about Indonesia Cover design by Holy Cow! Design & Advertising at the University of Melbourne, the Monash Centre of Printed and bound in Australia Typeset by Longueville Media in Esprit Book 10/13 Southeast Asian Studies, and the ANU’s Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies. After retiring in 1989 he National Library of Australia became Professor Emeritus and a Visiting Fellow in the Cataloguing-in-Publication data Indonesia Project at ANU. He was also Visiting Lecturer in the Melbourne Business School from 1996-2000. His Mackie, J. A. C. (James Austin Copland), 1924- . publications include Konfrontasi: the Indonesia-Malaysia Australia and Indonesia : current problems, future prospects. -

Boats to Burn: Bajo Fishing Activity in the Australian Fishing Zone

Asia-Pacific Environment Monograph 2 BOATS TO BURN: BAJO FISHING ACTIVITY IN THE AUSTRALIAN FISHING ZONE Asia-Pacific Environment Monograph 2 BOATS TO BURN: BAJO FISHING ACTIVITY IN THE AUSTRALIAN FISHING ZONE Natasha Stacey Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/boats_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Stacey, Natasha. Boats to burn: Bajo fishing activity in the Australian fishing zone. Bibliography. ISBN 9781920942946 (pbk.) ISBN 9781920942953 (online) 1. Bajau (Southeast Asian people) - Fishing. 2. Territorial waters - Australia. 3. Fishery law and legislation - Australia. 4. Bajau (Southeast Asian people) - Social life and customs. I. Title. (Series: Asia-Pacific environment monograph; 2). 305.8992 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Duncan Beard. Cover photographs: Natasha Stacey. This edition © 2007 ANU E Press Table of Contents Foreword xi Acknowledgments xv Abbreviations xix 1. Contested Rights of Access 1 2. Bajo Settlement History 7 3. The Maritime World of the Bajo 31 4. Bajo Voyages to the Timor Sea 57 5. Australian Maritime Expansion 83 6. Bajo Responses to Australian Policy 117 7. Sailing, Fishing and Trading in 1994 135 8. An Evaluation of Australian Policy 171 Appendix A. Sources on Indonesian Fishing in Australian Waters 195 Appendix B. Memorandum of Understanding Between the Government of Australia and the Government of the Republic of Indonesia Regarding the Operations of Indonesian Traditional Fishermen in Areas of the Australian Exclusive Fishing Zone and Continental Shelf (7 November 1974) 197 Appendix C.