Strengthening Tenure Security and Community Participation in Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Reform and Sustainable Livelihoods

! M4 -vJ / / / o rtr £,/- -n AO ^ l> /4- e^^/of^'i e i & ' cy6; s 6 cy6; S 6 s- ' c fwsrnun Of WVELOPMENT STUDIES LIBRARY Acknowledgements The researchers would like to thank Ireland Aid and APSO for funding the research; the Ministers for Agriculture and Lands, Dr. Kisamba Mugerwa and Hon. Baguma Isoke for their support and contribution; and the Irish Embassy in Kampala for its support. Many thanks also to all who provided valuable insights into the research topic through interviews, focus group discussions and questionnaire surveys in Kampala and Kibaale District. Finally: a special word of thanks to supervisors and research fellows in MISR, particularly Mr Patrick Mulindwa who co-ordinated most of the field-based activities, and to Mr. Nick Chisholm in UCC for advice and direction particularly at design and analysis stages. BLDS (British Library for Development Studies) Institute of Development Studies Brighton BN1 9RE Tel: (01273) 915659 Email: [email protected] Website: www.blds.ids.ac.uk Please return by: Executive Summary Chapter One - Background and Introduction This report is one of the direct outputs of policy orientated research on land tenure / land reform conducted in specific areas of Uganda and South Africa. The main goal of the research is to document information and analysis on key issues relating to the land reform programme in Uganda. It is intended that that the following pages will provide those involved with the land reform process in Kibaale with information on: • how the land reform process is being carried out at a local level • who the various resource users are, how they are involved in the land reform, and how each is likely to benefit / loose • empirical evidence on gainers and losers (if any) from reform in other countries • the gender implications of tenure reform • how conflicts over resource rights are dealt with • essential supports to the reform process (e.g. -

Accessibility to First-Mile Health Services: a Time-Cost Model for Rural Uganda

Social Science & Medicine 265 (2020) 113410 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Social Science & Medicine journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/socscimed Accessibility to First-Mile health services: A time-cost model for rural Uganda Roberto Moro Visconti a,*, Alberto Larocca b, Michele Marconi c a Department of Business Management, Catholic University of Sacred Heart, Via Ludovico Necchi, 7, 20123, Milan, Italy b Cosmo Ltd., A183/20, 11th Close South Odorkor Estate Greater Accra, Ghana c Universita` Politecnica delle Marche, Dipartimento di Scienze della, Vita e dell’Ambiente, Via Brecce Bianche, 60126, Ancona, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: This study estimates the geographical disconnection in rural Low-Middle-Income Countries (LMIC) between Barriers to care First-Mile suppliers of healthcare services and end-users. This detachment is due to geographical barriers and to a Remote diagnosis shortage of technical, financial,and human resources that enable peripheral health facilities to perform effective Geographic information systems and prompt diagnosis. End-users typically have easier access to cell-phones than hospitals, so mHealth can help Home-patient to overcome such barriers, transforming inpatients/outpatients into home-patients, decongesting hospitals, Results-based financing Healthcare cost-effectiveness especially during epidemics. This generates savings for patients and the healthcare system. The advantages of mHealth are well known, but there is a literature gap in the description of its economic returns. This study applies a geographical model to a typical LMIC, Uganda, quantifying the time-cost to reach an equipped medical center. Time-cost measures the disconnection between First-Mile hubs and end-users, the potential demand of mHealth by remote end-users, and the consequent savings. -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

Killing the Goose That Lays the Golden Egg

KILLING THE GOOSE THAT LAYS THE GOLDEN EGG An Analysis of Budget Allocations and Revenue from the Environment and Natural Resource Sector in Karamoja Region Caroline Adoch Eugene Gerald Ssemakula ACODE Policy Research Series No.47, 2011 KILLING THE GOOSE THAT LAYS THE GOLDEN EGG An Analysis of Budget Allocations and Revenue from the Environment and Natural Resource Sector in Karamoja Region Caroline Adoch Eugene Gerald Ssemakula ACODE Policy Research Series No.47, 2011 Published by ACODE P. O. Box 29836, Kampala Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Website: http://www.acode-u.org Citation: Adoch, C., and Ssemakula, E., (2011). Killing the Goose that Lays the Golden Egg: An Analysis of Budget Allocations and Revenue from the Environment and Natural Resource Sector in Karamoja Region. ACODE Policy Research Series, No. 47, 2011. Kampala. © ACODE 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. ACODE policy work is supported by generous donations and grants from bilateral donors and charitable foundations. The reproduction or use of this publication for academic or charitable purposes or for purposes of informing public policy is excluded from this restriction. ISBN 978997007077 Contents LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................. v LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................. -

Forests, Livelihoods and Poverty Alleviation: the Case of Uganda Forests, Livelihoods and Poverty Alleviation: the Case of Uganda

Forests, livelihoods and poverty alleviation: the case of Uganda Forests, livelihoods and poverty alleviation: the case of Uganda G. Shepherd and C. Kazoora with D. Mueller Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2013 The Forestry Policy and InstitutionsWorking Papers report on issues in the work programme of Fao. These working papers do not reflect any official position of FAO. Please refer to the FAO Web site (www.fao.org/forestry) for official information. The purpose of these papers is to provide early information on ongoing activities and programmes, to facilitate dialogue and to stimulate discussion. The Forest Economics, Policy and Products Division works in the broad areas of strenghthening national institutional capacities, including research, education and extension; forest policies and governance; support to national forest programmes; forests, poverty alleviation and food security; participatory forestry and sustainable livelihoods. For further information, please contact: Fred Kafeero Forestry Officer Forest Economics, Policy and Products Division Forestry Department, FAO Viale Delle terme di Caracalla 00153 Rome, Italy Email: [email protected] Website: www.fao.org/forestry Comments and feedback are welcome. For quotation: FAO.2013. Forests, Livelihoods and Poverty alleviation: the case of Uganda, by, G. Shepherd, C. Kazoora and D. Mueller. Forestry Policy and Institutions Working Paper No. 32. Rome. Cover photo: Ankole Cattle of Uganda The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression af any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

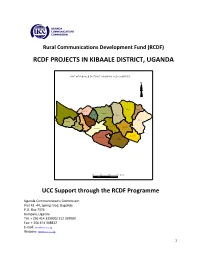

Rcdf Projects in Kibaale District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN KIBAALE DISTRICT, UGANDA MAP O F KIBAAL E DISTRIC T SHO WIN G SUB CO UNTIES N N alwe yo Kisiita R uga sha ri M pee fu Kiry a ng a M aba al e Kakin do Nko ok o Bw ika ra Ky an aiso ke Kag ad i M uho ro Kyeb an do Kasa m by a M uga ra m a Kib aa le TC Bwan s wa Bw am iram ira M atale 10 0 10 20 Kms UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..………....……3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….….…..……4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….….………..4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……...5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Kibaale district………….………..….5 2- Map of Uganda showing Kibaale district………..………………….………...……..….14 10- Map of Kibaale district showing sub counties………..…………………………..….15 11- Table showing the population of Kibaale district by sub counties…………..15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Kibaale district…………………………………….…….……..16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. -

Kibaale District Estimates.Pdf

Local Government Budget Estimates Vote: 524 Kibaale District Structure of Budget Estimates - PART ONE A: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures B: Detailed Estimates of Revenue C: Detailed Estimates of Expenditure D: Status of Arrears Page 1 Local Government Budget Estimates Vote: 524 Kibaale District A: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Revenue Performance and Plans 2013/14 2014/15 Approved Budget Receipts by End Draft Budget Dec UShs 000's 1. Locally Raised Revenues 670,245 305,658 622,009 2a. Discretionary Government Transfers 2,983,851 1,343,609 3,021,423 2b. Conditional Government Transfers 25,683,207 13,246,056 25,760,436 2c. Other Government Transfers 1,239,235 934,292 1,064,136 3. Local Development Grant 630,022 315,010 630,570 4. Donor Funding 625,438 100,550 625,438 Total Revenues 31,831,998 16,245,176 31,724,013 Expenditure Performance and Plans 2013/14 2014/15 Approved Budget Actual Draft Budget Expenditure by UShs 000's end of Dec 1a Administration 1,360,589 678,287 1,385,819 2 Finance 569,656 255,677 586,085 3 Statutory Bodies 1,191,672 633,033 881,088 4 Production and Marketing 3,527,916 1,862,626 3,414,448 5 Health 4,133,793 1,594,624 4,129,932 6 Education 15,885,248 8,358,540 15,862,642 7a Roads and Engineering 3,237,216 342,301 3,580,630 7b Water 503,557 204,243 528,906 8 Natural Resources 224,651 89,243 221,176 9 Community Based Services 790,471 287,371 760,471 10 Planning 233,769 110,342 219,681 11 Internal Audit 173,460 37,638 153,135 Grand Total 31,831,997 14,453,925 31,724,013 Wage Rec't: 17,375,141 8,567,467 17,375,141 Non Wage Rec't: 8,754,857 3,477,988 9,208,814 Domestic Dev't 5,076,562 2,323,174 4,514,621 Donor Dev't 625,438 85,295 625,438 Page 2 Local Government Budget Estimates Vote: 524 Kibaale District B: Detailed Estimates of Revenue 2013/14 2014/15 UShs 000's Approved Budget Receipts by End Draft Budget of Dec 1. -

The Republic of Uganda Kibaale District Local Government Statistical Abstract for Fy 2020/2021

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA KIBAALE DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT STATISTICAL ABSTRACT FOR FY 2020/2021 Kibaale District Local Government P.O Box 2, KARUGUUZA E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.kibaale.go.ug i FOREWORD The importance of statistics in informing planning and monitoring of government programmes cannot be over emphasized. We need to know where we are, determine where we want to reach and also know whether we have reached there. The monitoring of socio-economic progress is not possible without measuring how we progress and establishing whether human, financial and other resources are being used efficiently. However, these statistics have in many occasions been national in outlook and less district specific. The development of a district-based Statistical Abstract shall go a long way to solve this gap and provide district tailored statistics and will reflect the peculiar nature of the district by looking at specific statistics which would not be possible to provide at a higher level. Data and statistics are required for designing, planning, implementing, monitoring and evaluating development programmes. For instance, statistics on school enrolment, completion rates and dropout rates e.t.c are vital in the monitoring of Universal Primary Education and Universal Secondary Education programmes. Statistics are also needed for establishing grant aid to community schools, staff levels and other investments in the education programmes. The collection and use of statistics and performance indicators is critical for both the successful management and operation of the sectors, including Lower Local Governments. For data to inform planning and service delivery it should be effectively disseminated to the various users and stakeholders. -

In Uganda, but Full Equality with Men Remains a Distant Reality

For more information about the OECD Development Centre’s gender programme: [email protected] UGANDA www.genderindex.org SIGI COUNTRY REPORT Social Institutions & Gender Index UGANDA SIGI COUNTRY REPORT UGANDA SIGI COUNTRY Uganda SIGI Country Report The opinions expressed and arguments employed in this document are the sole property of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the OECD, its Development Centre or of their member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. © OECD 2015 UGANDA SIGI COUNTRY REPORT © OECD 2015 FOREWORD – 3 Foreword Uganda’s economic and political stability over the past two decades has brought unprecedented opportunities to address social inequalities and improve the well-being of citizens. Investments in key human development areas have reaped benefits in poverty reduction, and seen some improvements on a range of socio-economic indicators: but is everyone benefiting? Ugandan women and girls have partially benefited from these trends. New laws and measures to protect and promote women’s economic, political and human rights have been accompanied by impressive reductions in gender gaps in primary and secondary education and greater female political participation. Yet, wide gender gaps and inequalities remain, including in control of assets, employment and health. Economic development may have improved the status quo of women in Uganda, but full equality with men remains a distant reality. Tackling the discriminatory social norms that drive such gender inequalities and ensuring that women can equally benefit from Uganda’s development were twin objectives of this first in-depth country study of the OECD Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI). -

Oil Industry in Uganda: the Socio-Economic Effects on the People of Kabaale Village, Hoima, and Bunyoro Region in Uganda

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE 8-1-2016 Oil Industry in Uganda: The Socio-economic Effects on the People of Kabaale Village, Hoima, and Bunyoro Region in Uganda MIRIAM KYOMUGASHO Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation KYOMUGASHO, MIRIAM, "Oil Industry in Uganda: The Socio-economic Effects on the People of Kabaale Village, Hoima, and Bunyoro Region in Uganda" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 613. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/613 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the socio-economic effects of oil industry on the people of Kabaale Village, Hoima, and Bunyoro region in Uganda. The thesis analyses the current political economy of Uganda and how Uganda is prepared to utilize the proceeds from the oil industry for the development of the country and its people. In addition, the research examines the effects of industry on the people of Uganda by analyzing how the people of Kabaale in Bunyoro region were affected by the plans to construct oil refinery in their region. This field research was done using qualitative methods and the Historical Materialism theoretical framework guided the study. The major findings include; displacement of people from land especially women, lack of accountability from the leadership, and less citizen participation in the policy formulation and oil industry. -

Safeguarding the Forest Tenure Rights of Forest-Dependent Communities in Uganda INSIGHTS from a NATIONAL-LEVEL PARTICIPATORY PROSPECTIVE ANALYSIS WORKSHOP

Safeguarding the forest tenure rights of forest-dependent communities in Uganda INSIGHTS FROM A NATIONAL-LEVEL PARTICIPATORY PROSPECTIVE ANALYSIS WORKSHOP Concepta Mukasa1, Alice Tibazalika1, Baruani Mshale2, Esther Mwangi2 and Abwoli Y. Banana3 Key messages • Participatory Prospective Analysis (PPA) proved structures to promote community forest tenure; to be effective for encouraging collective reflection availability of technical staff with capacity to equip to identify threats to forest tenure security and to communities with knowledge and skills to enable develop ways for improving it at a national-level them to exercise their tenure rights; presence of workshop in Uganda, where stakeholders identified enterprising communities with skills to innovate several factors that strongly influence the forest and adopt alternatives to forestry products; and tenure rights of forest-dependent communities. effective enforcement of gender-sensitive forestry- • Factors influencing forestry tenure security that related laws and policies to promote benefit- they identified were: forest resource governance; sharing equity. community capacity to sustainably manage forests • After analyzing potential future outcomes, and demand/defend tenure rights; the priority level both negative and positive, PPA stakeholders of forestry and tenure security for development recommended prioritizing a set of actions to partners; local norms and beliefs that impact upon safeguard the future forest tenure security of forest- vulnerable groups’ tenure rights; forestry sector dependent communities. These actions were: financing in national budgetary allocations; and local improving coordination of key government agencies; communities’ legal literacy on land / forest tenure. adopting inclusive and participatory decision-making • When analyzing the potential evolution of forest processes for tenure-related activity implementation; tenure security over the next 25 years, stakeholders improving stakeholders’ technical and financial identified some desirable potential outcomes. -

Land Politics and Conflict in Uganda: a Case Study of Kibaale District, 1996 to the Present Day

7 Land Politics and Conflict in Uganda: A Case Study of Kibaale District, 1996 to the Present Day John Baligira Introduction This chapter examines how the interplay between politics and the competing claims for land rights has contributed to conflict in Kibaale district since 1996. It considers the case of Kibaale district as unique. First, as a result of the 1900 Buganda Agreement, 954 square miles of land (mailo land in Luganda language) which constituted 58 per cent of the total land in Buyaga and Bugangaizi counties of present Kibaale district was allocated by the British colonialists to chiefs and notables from Buganda. It is unique because there is no other district in Uganda, where most of the land is statutorily owned by people from outside that district. Second, people from elsewhere migrated massively to Kibaale district to the extent that they constitute about 50 per cent of the total population. No other district in Uganda has so far hosted new settlers constituting such a high percentage of its population. The chapter argues that the massive immigration and acquisition of land, the existence of competing land rights regimes, and the politicization of claims for land rights have contributed to conflict in Kibaale district (see map 1). 7- Land Politics.indd 157 28/06/2017 22:54:21 158 Peace, Security and Post-Conflict Reconstruction in the Great Lakes Region of Africa Map 7.1: Location of Kibaale district in Uganda Source: Makerere University Cartography Office, Geography Department, 2010 The ownership of mailo land in Buyaga and Bugangaizi counties by mostly Baganda was vehemently opposed by the Banyoro who considered themselves the original land owners.