From Orient to the Emirates the Plucky Rise of Burnley Fc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Set Checklist I Have the Complete Set 1958/59 A&BC Chewing Gum (English) Footballers, 2Nd Series (Planet, with Offer)

Nigel's Webspace - English Football Cards 1965/66 to 1979/80 Set checklist I have the complete set 1958/59 A&BC chewing gum (English) Footballers, 2nd series (Planet, with offer) 047 Doug Cowie Dundee 048 Derrick Sullivan Cardiff City 049 Wilbur Cush Leeds United 050 Albert Dunlop Everton 051 Robert (Bobby) Collins Celtic 052 Jeff Hall Birmingham City 053 Johnny Haynes Fulham 054 Ivor Allchurch Swansea City 055 John Atyeo Bristol City 056 Dave Bowen Arsenal 057 Ken Thomson Stoke City 058 Tommy Docherty Preston North End 059 Mel Charles Swansea City 060 Jimmy Dickinson Portsmouth 061 Stanley Matthews Blackpool 062 Jim Langley Fulham 063 Bedford Jezzard Fulham 064 Tommy Younger Liverpool 065 Allan Brown Luton Town 066 Wally Fielding Everton 067 Phil Gunter Portsmouth 068 Tom Jones Everton 069 Eddie Hopkinson Bolton Wanderers 070 George Cohen Fulham 071 Geoff Bradford Bristol Rovers 072 Tommy Johnston Blackburn Rovers 073 Bryan Douglas Blackburn Rovers 074 Ken Taylor Huddersfield Town 075 Ronnie Clayton Blackburn Rovers 076 Vic Metcalfe Huddersfield Town 077 Harry Gregg Manchester United 078 Robert (Bobby) Seith Burnley 079 Noel Cantwell West Ham United 080 Colin Webster Manchester United 081 Cliff Jones Tottenham Hotspur 082 Jimmy Adamson Burnley 083 Stan Mortensen Southport 084 Alf McMichael Newcastle United 085 Stewart Imlach Nottingham Forest 086 Doug Rudham Liverpool 087 Roy Bentley Fulham 088 Danny Blanchflower Tottenham Hotspur 089 Ken Rea Everton 090 Jimmy Tansey Everton 091 Maurice Setters West Bromwich Albion 092 Billy Bingham Luton Town This checklist is to be provided only by Nigel's Webspace - http://cards.littleoak.com.au/. -

Resource for Schools Sporting Heritage in the Academic Curriculum and Supporting Visits to Museums

Resource for Schools Sporting Heritage in the Academic Curriculum and Supporting visits to museums Sporting Heritage in the Academic Curriculum and Supporting visits to museums Contents: Page Part 3 1 Aim of this Resource 5 2 Examples of Sporting History and Heritage in the Academic Curriculum 10 3 Examples of Sporting Heritage and Cross- Curricular Opportunities in the Academic Curriculum 12 4 Sporting Heritage in School Assemblies 13 5 Events-led Programmes 19 6 Use of Artefacts and Visits to museums 21 7 National Sports Museum Online and Sport in Museums and their educational opportunities 31 8 Case Study: The Everton Collection 33 9 Case Study: Holybrook Primary School, Bradford, 2000-2014 35 Conclusion 1 Aim of this Resource The aim of this resource is to provide starting points for teachers who want to use sporting heritage in the academic curriculum. It also provides examples of sporting heritage programmes currently offered to support the curriculum in museum and sport settings across the country The physicality and accessibility of sport cuts through barriers of language, religion, class and culture. There is growing evidence that sporting heritage, taught as part of the school curriculum, is a very effective medium for motivating under-achieving pupils. Whilst the main academic focus of sporting heritage is history – most pertinently local history – it can also provide an effective springboard to cross-curricular learning and to sports participation. Many of our sports clubs were founded in the 19th century and, from Premier League football clubs to village cricket and rugby clubs, are often the best examples of living history in their communities, regularly attracting more people onto their premises and more interest in their fortunes than any other local organisations of comparable age. -

Application Recommended for Approval APP/2018/0140 Bank Hall Ward

Application Recommended for Approval APP/2018/0140 Bank Hall Ward Full Planning Application Demolition of existing stadium control box building and erection of 2 new corner stands (use class D2) to provide additional disability seating with ancillary facilities and lighting BURNLEY FOOTBALL CLUB TURF MOOR HARRY POTTS WAY BRUNSHAW ROAD BURNLEY Background: This application seeks to secure improved facilities for disabled supporters at Burnley Football Club. The scheme has been designed to meet the guidance of the Accessible Stadia Guide and is submitted in order to meet the Premier League deadline of August 2018. The application is a Full Planning Application for demolition of existing Stadium Control Box building and erection of 2 new corner stands (Use Class D2) to provide additional disability seating with ancillary facilities, lighting and associated advertisement consent application. Ancillary facilities include concession stands, toilets, accessible lift, changing places facility, store rooms, sensory room, under pitch heating boiler room, new Stadium Control Box, ticket office queuing space and new replacement Big Screen TV. The new infill corner buildings are designed to be both functional and aesthetically fitting. The elevation materials include glazing, polycarbonate, and glass fibre reinforced concrete panels. Imagery and careful use of the Club’s Claret and Blue colours are incorporated into the elevations to help immediately identify the new works as being part of Turf Moor, and perhaps form a new design direction for the stadium -

Football's Lost Decade

FOOTBALL’S Contrary to what Sky TV might have you believe, football did exist before 1992. In fact, the 1980s saw cultural and political change that shaped the modern game. But while LOST football wasn’t cool, some of us still loved it. Jon Howe looks back with nostalgia at the DECADE decade that football forgot... A game you might have forgotten Leeds United 1 Aston Villa 2 n August 16, 1980 The usual season-opening optimism was somewhat missing from Elland Road in August 1980. Despite the signing of Argentinean Alex Sabella for £400,000 from Sheffield United, Leeds fans were still smarting from a mediocre 11th-place finish the previous season, plus early and humiliating exits from both domestic cups and the UEFA Cup. It is safe to say that the words “Adamson out!” were not far from the vocal majority’s lips and they would be heard again before this afternoon was out. A Leeds fan in denial is a dangerous Alex Sabella in beast, and nobody liked to admit they action against were watching a club in transition, Aston Villa particularly when the direction of change was heading alarmingly the wrong way. That continued here, despite an explosive start when Brian Flynn earned a penalty in the opening exchanges, which was duly effort from Tony Morley. The England For Leeds it would be meagre fare for dispatched by Byron Stevenson after 177 winger was chief architect again on the much of another fruitless season. Jimmy seconds. In the searing heat Aston Villa hour when striker Gary Shaw bundled in Adamson was sacked and replaced by soon wrested control and with punishing the winner from close range. -

Felly's Football Tour Introduction 3

Felly’s Football Tour Sprint/Summer 2021 (tbc) Fundraising for Fellysfund in memory of our good friend The Motivation To Turf Moor To the University of Bolton Stadium Supporting Felly’s Fund To Deepdale To Goodison Park To Boundary Park Felly's Football Tour Introduction 3 Redwood Events have been arranging charity walks and cycle events since 2007 and have recently started to work with the Darby Rimmer MND Foundation. This has given us a great exposure to, and understanding of, the challenges that the Motor Neurone Disease can bring. Life changes very quickly for those diagnosed with MND and for their families. The average life expectancy for someone with Motor Neurone Disease is just 2-5 years from the onset of symptoms. A third of people diagnosed will die within a year and half within 2 years. It’s a 1/300 lifetime risk in the UK of being diagnosed with MND. That’s 3 children in each and every school today. There is no known cause of MND and there is no cure or effective treatment, it’s always fatal. When Paul Stanway talked to us about the great work they have done in memory of their great friend Felly, we were very keen to help. Felly’s Football Tour will combine a 131 mile continuous walking tour from Liverpool FC (Felly’s favourite team) to Fleetwood Town FC calling at fifteen other football grounds in between. This is a journey of 130 miles. After a short break for breakfast, the walking will give to cycling as riders will then head north from Fleetwood Town to Barrow AFC via Morecambe FC, a journey of 73 miles. -

Burnley's Locally Listed Buildings, Unscheduled Ancient Monuments

LOCALLY LISTED BUILDINGS, UNSCHEDULED ANCIENT MONUMENTS AND GARDENS OF SPECIAL HISTORIC INTEREST CLASSIFICATION BUILDINGS FORMERLY GRADE II ON PROVISIONAL LIST III OTHER LOCALLY LISTED BUILDINGS BY RESOLUTION OF THE COUNCIL L UNSCHEDULED ANCIENT MONUMENTS M GARDENS OF SPECIAL HISTORIC INTEREST WITH THEIR NUMBER ON THE SCHEDULE AND GRAD I, II* OR 88 AS SET OUT ABOVE. G43 (II) UPDATED SEPTEMBER 2001 1 LOCALLY LISTED BUILDINGS, UNSCHEDULED ANCIENT MONUMENTS AND GARDENS OF SPECIAL HISTORIC INTEREST LOCAL LIST LOCATION GRID LISTING REF. BRIERCLIFFE Nos. 2-10 (even) Acre St. L Nos. 2-12 (even) Banks St. Lane Bottom L Nos. 4-12 (even) (also Nos.1-2 Todmorden Rd) Burnley Rd. L Dr. Muir Memorial Drinking Fountain Burnley Rd. SD 869352 L No. 4 Chapel Court L Vicarage, St James’ Church Church St. L Fingerpost (Burnley R.D.C.) Halifax Rd. L Nos. 19-33 (odd) Halifax Rd. L Nos. 45-57 (odd) Halifax Rd., Lane Bottom L Nos. 69-93 (odd) Halifax Rd., Holt Hill L No. 95 Holt Hill Farm Halifax Rd. L No. 8 Former Briercliffe Reading and Recreation Room Halifax Rd. L No. 12 Halifax Rd L Nos. 20-32 (even) Halifax Rd., Hill End L Nos. 52-62 (even) Halifax Rd., L Ebenezer Baptist Chapel & Sunday School Halifax Rd., Lane Bottom L UPDATED SEPTEMBER 2001 2 LOCALLY LISTED BUILDINGS, UNSCHEDULED ANCIENT MONUMENTS AND GARDENS OF SPECIAL HISTORIC INTEREST LOCATION GRID LISTING REF. Hill Farmhouse (Nos. 64 &66) Halifax Rd., Lane Bottom III No. 68 Halifax Rd. L Windle House Halifax Rd. SD 889352 L Widdup Cross Halifax Rd SD 915337 M Arncliffe, Hill End (Off) Halifax Rd. -

The Peterite

THE PETERITE Vol. LXI FEBRUARY, 1970 No. 382 EDITORIAL John Bunyan's pilgrims were shown, in the Interpreter's House, "a man that could look no way but downwards, with a muck-rake in his hand," and the man could not see the crown offered to him because he did not look up. "Where there's muck there's money" is well-known to us, and there can have been few decades that have borne this out more fully than the decade of the sixties now passed. Obscene books, obscene films, obscene "plays" have certainly brought in the money for their unremem- bered authors, producers and actors. Memoirs of prostitutes and criminals have brought easy wealth; a drug offence has become almost essential publicity for some. Decent discretion is now labelled hypocrisy, and skeletons that used to be in cupboards are now expected to be proudly displayed. Writers of "plays" have turned a quick penny by shooting little arrows at long-accepted heroes; the writers' names are soon forgotten, but those at whom they have shot have had an awkward habit of standing secure, unsullied: Havelock, Nightingale, Churchill, Nelson. Not to be out-done, some churchmen have jumped on the wagon. At first it was to help prove the literary merit of "Lady Chatterley's Lover". Then a new "humanism" became the vogue, and a clerical collar became the badge of the avant-garde, provided its wearer was disproving the divinity of Christ, or "rationalising" the faith by which he is presumed to live. The man with the muck-rake certainly had his head well down. -

Jimmy Adamson Jimmy Adamson the Man Who Said ‘No’ to England

JIMMY JIMMY ADAMSON JIMMY ADAMSON THE MAN WHO SAID ‘NO’ TO ENGLAND DAVE THOMAS FOREWORD BY SIR BOBBY CHARLTON Contents Acknowledgements 7 Foreword by Sir Bobby Charlton 9 1 Fetch my luggage 12 2 Send me a winger 26 3 Alan, Bob and Harry too 47 4 Through the 1950s 66 5 Peak season 1961/62 and a World Cup 88 6 From player to coach 107 7 1970 takeover and a prediction 127 8 A time of struggle 144 9 Goodbye Ralphie and a test of endurance 159 10 1973 triumph 176 11 Back at the top 194 12 Almost the ‘Team of the Seventies’ 210 13 Horribilis, Blackpool, January 1976 226 14 Genius but not everyone’s cup of tea 246 15 Sunderland via Rotterdam 268 16 Leeds United 298 17 Goodbye football 314 Finale 334 References 350 Chapter 1 Fetch my luggage ONLY ever managed to speak to Jimmy Adamson once. It must have been sometime in 2005 and I knew that by then I he rarely spoke to people about football. He’d had nothing to do with the game since the time he left Leeds United in 1980. They had joked there that he was the Yorkshire Ripper. The police used to go round the pubs of Leeds and play the infamous hoax tape of the Geordie voice belonging to the guy who claimed to be the Ripper. They would ask, ‘Does anyone recognise this voice?’ Voices would shout back, ‘It’s Jimmy bloody Adamson.’ By 1980 he was none too popular at Elland Road. -

Moving April 2013 Toa Different Beat E’Re Back - Welcome to the Footballing Greats Like Franz Beckenbauer New Editi on of Moving to a and George Best

Cardiff City Supporters’ Trust Magazine moving April 2013 toa different beat e’re back - welcome to the footballing greats like Franz Beckenbauer new editi on of Moving To A and George Best. contents Diff erent Beat. Media Wales journalist Steve Tucker W writes an entertaining piece as he gives It’s been a while since our last magazine, although we’ve not been sitti ng on our his take on following the Bluebirds while laurels. We produced the commemorati ve we also tell you about the highlights of the 1983 promoti on celebrati on, brochure to mark the completi on and A Word from the Chair erecti on of the fantasti c Fred Keenor plus all the latest Trust news, statue. including the recent fans’ 4 survey. This season has certainly been volati le off the fi eld with the rebranding controversy I hope you enjoy the read In safe hands: David while on it the Bluebirds have been and as ever, if you want Marshall Interview to get involved, 6 pushing hard for promoti on to the Premier League. We wish the team well [email protected] as they bid to reach the top division for or the fi rst ti me in more than 50 years. The Votes are in CCST 11 Key to the success of any team is a solid PO Box 4254 defence and goalkeeper David Marshall, CARDIFF a rock between the sti cks, took ti me out CF14 8FD Class of ‘83: from training to talk to us about his life at Promoti on Evening Cardiff City and starring for Celti c against 12 Barcelona. -

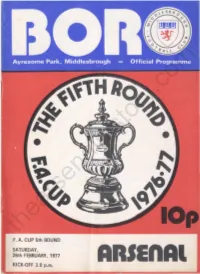

Thearsenalhistory.Com F

thearsenalhistory.com F. A. CUP Sth ROUND SATURDAY, 26th FEBRUARY I 1977 ARSEftAl KICK-OFF 3.0 p.m. mlDDlESBROUGH P.C. Half•Timc & ATHlETIC CO. lTD. TE Am Sco1c1 AYRESOME PARK. MIDDLESBROUGH . CLEVELAND TS1 4PE . Telephone: 89659/ 85996 DIRECTORS: C . Amer (Chairman). Dr. U . N. Philli ps (V ice-Cha irman) . G . T . Ki t c h ing . E. V arl e y . J . D . Hatfield . M . McCul l agh , K. C . Amer. E. K. Varley . MANAGER: J . Charlton O .B.E. SHEET SECRETARY : T . H . C . Green . ASSISTANT MANAGER : H . Shepherd son M .B. E. KEY No. 1 ORANGE C LUB HONOURS: A Aston Villa v Port Va le Second D i v i s i on Champions 1926/ 27-1928/ 29- 1973/ 74 A nglo-Scottish Cup Winners 1915/ 76 B Cardiff v Everton 8010 C Derby v Blackburn R. D Wolves v Chester as something fresh. Arse nal w ill be a 1 Pat CUFF E Leeds v Manchester C. different kettle of fish today and there is F Liverpool v Oldham mc11agc f1om no way they w ill come and play the way 2 John CRAGGS they did 11 days ago. it is qu ite probable that the injured players w ill be returning 3 Terry COOPER to the team improving their all-round 4 Graeme SOUNESS KEY No. 2 GREEN the manage•: strength and mobility. A Southampton v Manchester U. B Coventry v West Brom. Your support in recent matches has 5 Stuart BOAM THE CHANGING FORTUNES been tremendous and I hope that by the C Q.P.R . -

Burnley Task Force Report

BURNLEY TASK FORCE Page No CONTENTS 1-3 LISTEN TO US 4 PREFACE 5-6 CHAIR’S INTRODUCTION 7-9 TASK FORCE RECOMMENDATIONS AND ACTION PLAN 10-23 MAPS OF BURNLEY 24-26 SECTION 1 1.1 The origins of the Task Force, its 27-30 Membership and Terms of Reference 1.2 The First Meeting 30-31 1.3 The Consultation Process 31-34 SECTION 2 2.1. What Happened? 35-36 2.2. Why Did it Happen? 36-37 SECTION 3 3.1. Submissions and Task Force Responses 38-39 3.2. Housing 39-47 3.2.1. Ways Forward 3.2.2. Housing Market Renewal Fund 3.2.3. Partnership Management 3.2.4. The Borough’s Approach 3.2.5. Information from other Local Authorities 3.2.6. Private Landlords Page 1 of 87 3.2.7. Housing and Landlords Associations 3.3. Community Relations 4753 3.3.1. Funding of Race Relations Work 3.3.2. The Politicisation of Race 3.3.3. The Asian Heritage Communities 3.3.4. The White Community 3.4. Community and Voluntary Sector 54-57 3.5. Burnley Borough Council 58-62 3.5.1. Council’s Submission 3.6. Police 63-65 3.7. Summary of Newspaper Media Analysis 65-67 3.8. Education 67-68 3.9. Young People 68-77 3.9.1. How the Young People’s Group Operated 3.9.2. How the views of Young People were Obtained 3.9.3. Young People’s Questionnaire 3.9.4. Web Page and ROBOT 3.9.5. -

Club Sponsor

CLUB SPONSOR BOSHAM XI v PORTSMOUTH LEGENDS Club & Portsmouth FC Benevolent Fundraiser Sunday, November 16, 2014 Kick-Off: 1.00pm COMMEMORATIVE EDITION Bosham Football Club The Recreation Ground, Walton Lane, Bosham, West Sussex, PO18 8QF Tel: 01243 681279 Formed 1901 Affiliated to the Sussex County Football Association Members of the Sussex County Football League & Charter Standard Club www.boshamfc.co.uk President: Chairman & Secretary: Bob Probee Alan Price T: 07832 239826 Vice Presidents E: [email protected] Geraldine Doncaster Dennis Phillips Vice Chairman: Dave Stear John Redman Life Members: Match Secretary: Geraldine Doncaster Neil Holley -Williams Richard Doncaster First Team Player/ Manager: George Hammond Andy Probee Brian Kearvell Michael Maiden First Team Player/ Assistant Manager: Bob Probee Neil Redman Dave Smith Head Coach: Derek Smith Grahame Vick Committee Members: Reserve Team Manager: Ben Blanshard Frank Antony Mat Jackson (& Treasurer) Club Captain: Andy Probee James Wilson Neil Redman Sports Therapist: Child Welfare Officer: Jodie Hope Nikki Webb Commercial Manager: Cover Artwork: Simon Jasinski Charles Fearn E: [email protected] Honours Sussex County League Division Three Sussex Intermediate Cup Champions: 1993/94, 1999/00, 2009/10 Runners-up: 2004/05, 2008/09 Runners-up: 1984/85 Malcolm Simmonds Memorial Cup Sussex County League – Winners: 1998/99 Highest Placed Finish West Sussex Football League 7th - Division Two – 1985/86, 1994/95 West Sussex Football League Centenary Cup Winners: 1998/99 Premier Division