TYLER HAMILTON MAD LIKE TESLA Tyler Hamilton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PATH Underground Walkway

PATH Marker Signs ranging from Index T V free-standing outdoor A I The Fairmont Royal York Hotel VIA Rail Canada H-19 pylons to door decals Adelaide Place G-12 InterContinental Toronto Centre H-18 Victory Building (80 Richmond 1 Adelaide East N-12 Hotel D-19 The Hudson’s Bay Company L-10 St. West) I-10 identify entrances 11 Adelaide West L-12 The Lanes I-11 W to the walkway. 105 Adelaide West I-13 K The Ritz-Carlton Hotel C-16 WaterPark Place J-22 130 Adelaide West H-12 1 King West M-15 Thomson Building J-10 95 Wellington West H-16 Air Canada Centre J-20 4 King West M-14 Toronto Coach Terminal J-5 100 Wellington West (Canadian In many elevators there is Allen Lambert Galleria 11 King West M-15 Toronto-Dominion Bank Pavilion Pacific Tower) H-16 a small PATH logo (Brookfield Place) L-17 130 King West H-14 J-14 200 Wellington West C-16 Atrium on Bay L-5 145 King West F-14 Toronto-Dominion Bank Tower mounted beside the Aura M-2 200 King West E-14 I-16 Y button for the floor 225 King West C-14 Toronto-Dominion Centre J-15 Yonge-Dundas Square N-6 B King Subway Station N-14 TD Canada Trust Tower K-18 Yonge Richmond Centre N-10 leading to the walkway. Bank of Nova Scotia K-13 TD North Tower I-14 100 Yonge M-13 Bay Adelaide Centre K-12 L TD South Tower I-16 104 Yonge M-13 Bay East Teamway K-19 25 Lower Simcoe E-20 TD West Tower (100 Wellington 110 Yonge M-12 Next Destination 10-20 Bay J-22 West) H-16 444 Yonge M-2 PATH directional signs tell 220 Bay J-16 M 25 York H-19 390 Bay (Munich Re Centre) Maple Leaf Square H-20 U 150 York G-12 you which building you’re You are in: J-10 MetroCentre B-14 Union Station J-18 York Centre (16 York St.) G-20 in and the next building Hudson’s Bay Company 777 Bay K-1 Metro Hall B-15 Union Subway Station J-18 York East Teamway H-19 Bay Wellington Tower K-16 Metro Toronto Convention Centre you’ll be entering. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Great Towers and landmarks worldwide unite in global show support for Australia on Jan. 26 TORONTO, Jan. 24 — The CN Tower, fellow members of the World Federation of Great Towers and landmarks around the world are uniting to raise awareness and show support for Australia as the country works to fight and recover from devastating wildfires. On the night of Australia’s national holiday, January 26, the CN Tower will be among many landmarks to light in the country’s national colours of green and gold. Still others plan to join in the effort through social media and online. To date, towers and landmarks that have confirmed their participation include: • The Berlin TV Tower, Berlin, Germany • Busan Tower, Jung Gu, Busan, South Korea • The Calgary Tower, Calgary, Canada • The CN Tower, Toronto, Canada • The Eiffel Tower, Paris, France • The Empire State Building, New York, USA • Euromast, Rotterdam, Netherlands • La Grande Roue, Montréal, Canada • N Seoul Tower, Seoul, South Korea • Niagara Falls, Niagara Falls, Canada/USA • One Liberty, Philadelphia, USA • The Reunion Tower, Dallas, USA • The Royal Liver Building, Liverpool, UK • The Shard, London, UK • SkyTower, Auckland, New Zealand • The Tokyo Tower, Tokyo, Japan • Toronto sign, Toronto, Canada • The Willis Tower, Chicago, USA “Australia is facing some of the worst wildfires ever seen. The scale of the ongoing crisis and its impact on the environment, people and wildlife concerns all of us around the world,” says Peter George, the CN Tower’s Chief Operating Officer. “Under the circumstances, we felt a global show of 1 support would be meaningful to many. -

Per Molti Secoli L'uomo Potè Attuare La Trasmissione Di Informazioni A

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI “FEDERICO II” POLI DELLE SCIENZE E DELLE TECNOLOGIE FACOLTÀ DI ARCHITETTURA DIPARTIMENTO DI CONFIGURAZIONE ED ATTUAZIONE DELL’ARCHITETTURA Dottorato in Tecnologia e Rappresentazione dell’Architettura e dell’Ambiente XVIII Ciclo Indirizzo: Rilievo e Rappresentazione dell’Architettura e dell’Ambiente - Settore Scientifico Disciplinare: ICAR/17- Tesi di Dottorato di Ricerca COMUNICAZIONE, TRASMISSIONE E SEGNI. LE TORRI EMITTENTI E RICEVENTI. Dottorando Docente Tutor Angelo Vallefuoco Prof. Arch. Mariella dell’Aquila Coordinatore d’indirizzo Coordinatore Prof. Arch. Mariella Dell’Aquila Prof. Arch. Virginia Gangemi 1 2 Indice Premessa 5 Capitolo primo LE TELECOMUNICAZIONI origini e sviluppo 9 1.1 - Le origini 9 1.2 - I primi passi delle comunicazioni elettriche 12 1.3 - Gli esordi delle telecomunicazioni in Italia 17 1.4 - Le telecomunicazioni italiane dal 1925 al 1945 26 1.5 - La ricostruzione degli impianti dopo gli eventi bellici del 1940/45 30 1.6 - Le telecomunicazioni italiane dal 1948 al 1980 31 1.7 - Le nuove frontiere delle telecomunicazioni ai nostri giorni 38 Capitolo secondo SISTEMI PER TRANS-MITTERE apparati emittenti e riceventi 45 2.1 - Sistemi di trasmissione 45 I segnali 46 I canali di comunicazione a distanza 47 Il "rumore" 50 Modello di un sistema di trasmissione 50 Le reti di telecomunicazione 52 Capitolo terzo FORMA E FUNZIONI evoluzione delle architetture per le telecomunicazioni 55 3.1 - I precursori delle torri di telecomunicazioni 55 3.2 - La torre Eiffel: simbolo della tecnica innovatrice del XIX secolo 56 3.3 - La Fernsehturm di Berlino: metafora e ideologia 62 3.4 - Forma e struttura: la torre di Collserola 69 3.5 - Natura e artificio: le torri per le comunicazioni di Calatrava 76 Conclusioni 81 Appendice: Le torri per le comunicazioni 85 Riferimenti bibliografici 129 3 4 Premessa La costruzione di una torre è uno dei sogni più grandi dell’umanità. -

Uwindsor Engineering OUTREACH

UWindsor Engineering OUTREACH Building Earthquake Resistant Structures: Grades 9 to 10 YOUR MISSION In this activity, you will use marshmallows and toothpicks to design a structure that is capable of resisting the forces experienced during an earthquake. There are two shapes used in designing and strengthening buildings, squares and triangles. In building design, these are called trusses and cross bracing members. You will gain experience in designing a building and learning about the types of energy released by an earthquake. Watch this video to learn about the world’s largest shaker platform. WHAT’S GOING ON Engineers are problem solvers and they come up with solutions to problems to better the lives of everyone around them. They do this by coming up with designs, products, technologies, innovations, procedures and systems to make the world a better place. Civil Engineers are responsible for designing buildings and structures. Two of the more well-known structures in the world are the Eiffel Tower in Paris and the CN Tower in Toronto (Figure 1). Civil Engineers have to make sure they design earthquake-resistant buildings to protect people and property and ensuring the safety of all those who are using them. They can test their designs by simulating the effect natural disasters, such as earthquakes, tsunamis and hurricanes, have on their designs and on the strength of their materials used prior to the actual construction of the buildings. Figure 1: Eiffel Tower (Paris, France) and CN Tower (Toronto, Canada) UWINDSOR.CA/ENGINEERING/OUTREACH In addition to the vertical force of gravity, buildings must also deal with the horizontal force of the wind. -

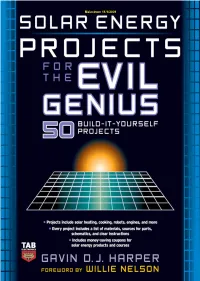

Solar Energy Projects for the Evil Genius : [50 Build

Malestrom 11/1/2009 Solar Energy Projects for the Evil Genius Evil Genius Series Bionics for the Evil Genius: 25 Build-it-Yourself MORE Electronic Gadgets for the Evil Genius: Projects 40 NEW Build-it-Yourself Projects Electronic Circuits for the Evil Genius: 57 Lessons 101 Spy Gadgets for the Evil Genius with Projects 123 PIC® Microcontroller Experiments for the Evil Electronic Gadgets for the Evil Genius: Genius 28 Build-it-Yourself Projects 123 Robotics Experiments for the Evil Genius Electronic Games for the Evil Genius PC Mods for the Evil Genius: 25 Custom Builds to Electronic Sensors for the Evil Genius: Turbocharge Your Computer 54 Electrifying Projects Solar Energy Projects for the Evil Genius 50 Awesome Auto Projects for the Evil Genius 25 Home Automation Projects for the Evil Genius 50 Model Rocket Projects for the Evil Genius Mechatronics for the Evil Genius: 25 Build-it-Yourself Projects Solar Energy Projects for the Evil Genius GAVIN D. J. HARPER New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2007 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a data- base or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-150910-0 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-147772-1. -

Renewable Energy Use in the World and Armenia

USE OF RENEWABLE ENERGY SOURCES IN THE WORLD AND ARMENIA THROUGH INNOVATIONS TO CLEAR TECHNOLOGIES YEREVAN - 2010 USE OF RENEWABLE ENERGY SOURCES IN THE WORLD AND ARMENIA THROUGH INNOVATIONS TO CLEAR TECHNOLOGIES United States Alumni Association of Armenia US Embassy, Yerevan, PAS office, USG Alumni Outreach Grant Program “EcoTeam” - Energy and Environmental Consulting NGO United Nations Development Program Global Environment Facility “Enabling Activities for the Preparation of Armenia’s Second National Communication to the UNFCCC” UNDP/GEF Project (2006-2009) YEREVAN - 2010 United States Alumni Association of Armenia US Embassy, Yerevan, PAS office, USG Alumni Outreach Grant Program “EcoTeam” - Energy and Environmental Consulting NGO United Nations Development Program Global Environment Facility “Enabling Activities for the Preparation of Armenia’s Second National Communication to the UNFCCC” UNDP/GEF Project (2006-2009) PREFACE The English version of brochure is prepared by Artashes Sargsyan, PhD, alumnus of IVLP program in frames of grant from United States Alumni Association of Armenia (USAAA) with support from US Embassy, Yerevan, PAS office, USG Alumni Outreach Grant Program in collaboration with ―EcoTeam‖-Energy and Environmental consulting NGO and ―Enabling Activities for the Preparation of Armenia’s Second National Communication to the UNFCCC‖ UNDP/GEF Project in 2010. The brochure is recommended by the Chair of ―Semiconductor Physics and Microelectronics‖ of Radiophysics Faculty of the Yerevan State University and the Chair of ―Industrial Enterprise Economy, Organization, Planning and Energy‖ of the Energy Faculty of the Armenian State Engineering University to use in the ―Alternative Energy Sources‖ Subject. ―Renewable Energy Use in the World and in Armenia. Through Innovations towards Clean Technologies.‖ Yerevan. -

Fairmont Royal York Toronto

FAIRMONT ROYAL YORK TORONTO WELCOME TO FAIRMONT ROYAL YORK _______________________________________________________________________________________________ Fairmont Royal York is located in the heart of Downtown Toronto, and is just steps away from the city’s biggest sites and attractions including: The CN Tower, Ripley’s Aquarium of Canada, Air Canada Centre, Rogers Centre, the Eaton Centre, and the Sony Centre for the Performing Arts. )DLUPRQW5R\DO<RUNUHFHQWO\FRPSOHWHGLWVÀYH\HDUPXOWLPLOOLRQGROODUJXHVWURRPUHYLWDOL]DWLRQ0RUH /X[XU\DQG6LJQDWXUH5RRPVDFURVVÁRRUVDUHFXUUHQWO\DYDLODEOHIRUWKHFRPIRUWRIRXUJXHVWV 7KHVHQHZO\UHGHVLJQHGURRPVDUHDIUHVKPRGHUQDGGLWLRQWRWKHUHJDOHOHJDQFHWKDWLVV\QRQ\PRXV with the hotel. :HDOVRLQYLWH\RXWRLQGXOJHLQWKHFXOLQDU\FUHDWLRQVRIRXU([HFXWLYH&KHI·VDZDUGZLQQLQJWHDP Choose from six dining establishments with seasonal herbs from our rooftop garden and honeybee apiary brightening each dish. HISTORY OF THE HOTEL ____________________________________________ On June 11, 1929WKHKRWHORIÀFLDOO\RSHQHG as The Royal York. It was the tallest building in the British Commonwealth and quickly set the KRVSLWDOLW\VWDQGDUGRIWKHGD\7KHPDJQLÀFHQW hotel became known as a city within a city, ULVLQJLQÁRRUVRIDUFKLWHFWXUDOVSOHQGRUDQG replete with mechanical genius and opulence QHYHUEHIRUHVHHQLQ7RURQWR,WERDVWHG URRPVHDFKZLWKUDGLRVSULYDWHVKRZHUVDQG bathtubs. The 1.5 acres of public rooms LQFOXGHGDEHGKRVSLWDOERRN OLEUDU\DQGWHQRUQDWHSDVVHQJHUHOHYDWRUV The Concert Hall featured a full stage and PDPPRWKSLSHRUJDQZHLJKLQJWRQVZKLFK VXUSDVVHGDQ\WKLQJHOVHLQ&DQDGDZLWK -

General Information

General Information Defining the Toronto skyline at 553.33m (1,815ft5in) the CN Tower is Canada's most recognizable and celebrated icon. The CN Tower is an internationally renowned architectural triumph, an engineering Wonder of the Modern World, world-class entertainment and dining destination and a must see for anyone visiting Toronto. Each year, over 1.5 million people visit Canada’s National Tower to take in the breathtaking views and enjoy all the CN Tower has to offer. Take in spectacular views of up to 160km (100 miles) away from three observation levels, including the world famous Glass Floor and the outdoor SkyTerrace with a view 1,122 feet straight down to the ground and the SkyPod, at 447m the highest of them all. Open seasonally from May-October, EdgeWalk at the CN Tower is the most exciting extreme attraction in the Tower’s history. Three restaurants on property satisfy every appetite. Enjoy award-winning fine dining at 360 The Restaurant at the CN Tower, upscale bistro dining at Horizons and casual fare at Le Café. Attractions include a state-of-the-art theatre with 3D and 4D capabilities, considered one of the most technically advanced venues in Canada, the Himalamazon motion theatre ride, Arcade, and 10,000 square feet of unique Canadian artisan souvenir shopping in the Gift Shop. Visual displays throughout the building share many fascinating stories about this engineering marvel. Toronto’s ultimate event venue, the CN Tower hosts over 500 events each year from receptions and dinners to products launches and themed events for 2 to 2000 people. -

City Branding: Part 2: Observation Towers Worldwide Architectural Icons Make Cities Famous

City Branding: Part 2: Observation Towers Worldwide Architectural Icons Make Cities Famous What’s Your City’s Claim to Fame? By Jeff Coy, ISHC Paris was the world’s most-visited city in 2010 with 15.1 million international arrivals, according to the World Tourism Organization, followed by London and New York City. What’s Paris got that your city hasn’t got? Is it the nickname the City of Love? Is it the slogan Liberty Started Here or the idea that Life is an Art with images of famous artists like Monet, Modigliani, Dali, da Vinci, Picasso, Braque and Klee? Is it the Cole Porter song, I Love Paris, sung by Frank Sinatra? Is it the movie American in Paris? Is it the fact that Paris has numerous architectural icons that sum up the city’s identity and image --- the Eiffel Tower, Arch of Triumph, Notre Dame Cathedral, Moulin Rouge and Palace of Versailles? Do cities need icons, songs, slogans and nicknames to become famous? Or do famous cities simply attract more attention from architects, artists, wordsmiths and ad agencies? Certainly, having an architectural icon, such as the Eiffel Tower, built in 1889, put Paris on the world map. But all these other things were added to make the identity and image. As a result, international tourists spent $46.3 billion in France in 2010. What’s your city’s claim to fame? Does it have an architectural icon? World’s Most Famous City Icons Beyond nicknames, slogans and songs, some cities are fortunate to have an architectural icon that is immediately recognized by almost everyone worldwide. -

CN Tower Has Been a Source of Pride of Accomplishment for Canadians

Since it opened 21 years ago, the CN Tower has been a source of pride of accomplishment for Canadians. It is truly a wonder of modern design, engineering and construction. At a height of 553.33m (1,815 ft, 5 inches), it is the World's Tallest Building and Free- Standing Structure, an important telecommunications hub, and the centre of tourism in Toronto. Each year, approximately 2 million people visit the world's tallest building to celebrate its achievement, take in the breathtaking view and enjoy all of the attractions the CN Tower has to offer. History superimposed over another. In effect, The Tower inspires a sense of pride, they were watching two shows at once. inspiration and awe for Canadians and And this was before channel surfing tourists alike. However, its origins are allowed us to do this on purpose. It firmly rooted in practicality. became clear that what we needed was an antenna that would not only be taller During Toronto's building boom in the than any building in the city, but one that early 70's, a serious problem was would be taller than anything that would developing. People were experiencing probably ever be built. poor quality television. And it wasn't just the sitcoms. The pre-skyscraper In 1972, Canadian National (CN) set out transmission towers of Toronto stations to build a tower that would solve the were simply not high enough anymore. communications problems, serve as a world class entertainment destination, As office buildings were reaching higher and achieve international recognition as and higher, TV and radio reception the world's tallest tower. -

Diplomprüfung Nebenthemas "Fernsehtürme"

FERNSEHTÜRME Anna Lederer Matrikelnr. 11036479 Diplom Nebenthema 2008 Köln International School of Design Betreut von Prof. Michael Gais IM BUCH EINLEITUNG 7 SELBSTDARSTELLUNG 58 Logos 59 TURMBAU 8 Wie soll er denn heissen? 61 Pharos und Turm zu Babel 8 Der Turm im Buch 62 Eiffelturm 10 Der Turm als Werbefträger 68 Die Werbewelle, Donauturm Wien 70 ES FUNKT 12 Vom Funk- zum Fernsehturm 14 DER TURM ALS SYMBOL 72 Berlin 74 stahl versUS betON 16 GUTE TYPEN 17 DAS VERLASSENE SCHIFF 81 DIE BAUMEISTER 19 Viva Colonius? 82 SONDERTÜRME 20 Goldene Zeiten 84 Der Hamburger 90 SCHAFFE, SCHAFFE, TÜRMLE BAUE Die Ruine 92 Der Stuttgarter Fernsehturm 22 Liebe deinen Turm 93 Oft kopiert – nie erreicht? 27 Bürgerturm 94 Der Schaft in Toronto 28 Uhren in Düsseldorf 30 ZUM SCHLUSS 96 Das Ei – Nürnberg 32 Die Kugel – Berlin 34 LITERATUR 98 Im Häusermeer – Frankfurt 36 BILDMATERIAL 99 Nah am Wasser gebaut – Ontario 40 PERSONEN 100 WER HAT DEN HÖCHSTEN? Der Fernsehturm in Ostankino 42 ROTATION UND HYDROKULTUR – DIE DREHRESTAURANTS 44 Florianturm Dortmund 46 Olympiaturm München 48 EINLEITUNG Fernsehtürme stehen in fast jeder größeren Stadt und ziehen Besucher aus der ganzen Welt an. Sie locken mit einer Fahrt in die Höhe, einer tollen Aussicht und einem Stück Kuchen oben im Turmcafé im Charme der 1960er. Das zumindest denke ich, bevor ich mit mei- ner Arbeit zu den Fernsehtürmen beginne. Mich interessiert, welchen Nutzen die Türme heute haben und ob sie für die Funktechnik überhaupt noch gebraucht werden. Dreht sich der Turm oder das Restaurant? Warum stehen so viele Türme leer und was passiert mit ihnen? Was bedeuten die Fernsehtürme für die Bewoh- ner einer Stadt? Diesen und anderen Fragen möchte ich in mei- ner Arbeit auf den Grund gehen. -

Hotel Descriptions

2019 AERA Annual Meeting ● April 5-9, 2019 ● Toronto, ON, Canada Hotel Descriptions Hotel Name Hotel Picture Description Chelsea Hotel, Toronto is located in the heart of downtown, just steps from the city’s best shopping districts, world-class theatres, vibrant nightlife and exciting attractions. The hotel features 1,590 guestrooms, three restaurants and separate adult and family recreation areas – including an adult-only sun deck and the Chelsea Hotel Toronto “Corkscrew” downtown Toronto’s only indoor waterslide. Outstanding service coupled with a unique range of facilities; provide travellers with essential amenities and comfortable accommodations at an exceptional value. Experience the newly renovated largest full-service Courtyard by Marriott in the world, one of the great downtown Toronto, Ontario hotels near shopping in Bloor Yorkville, Eaton Centre, entertainment, business and subway transit. Guests will appreciate redesigned guest rooms with a residential feel, tone-on-tone décor offering Courtyard by Marriott Downtown relaxation and abundant comfort along with stylish bathrooms, new Marriott beds, in-room safes, mini fridges, in-room coffee/tea, 60 TV channels and FREE Wi-Fi! Toronto Discover GoBoard ® technology that offers touch screen capabilities with news, local information, restaurants to map out your stay around the hotel in downtown Toronto, Ontario. The refreshed lobby Bistro offers healthy food and beverage options, proudly serving Starbucks® coffee and cocktail options. Our hotel in the heart of downtown Toronto has 575 spacious guestrooms, a 24 hour fitness centre, indoor lap pool, valet parking, and more! Nestled between the Air Canada Centre and the Rogers Centre and directly connected to the Metro Toronto Convention Centre south building via the PATH, the Delta Toronto is the anchor of the city’s coolest new neighbourhood, Southcore (Soco).