Management Education in Nepal: a View from the High Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEPAL: Preparing the Secondary Towns Integrated Urban

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 36188 November 2008 NEPAL: Preparing the Secondary Towns Integrated Urban Environmental Improvement Project (Financed by the: Japan Special Fund and the Netherlands Trust Fund for the Water Financing Partnership Facility) Prepared by: Padeco Co. Ltd. in association with Metcon Consultants, Nepal Tokyo, Japan For Department of Urban Development and Building Construction This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. TA 7182-NEP PREPARING THE SECONDARY TOWNS INTEGRATED URBAN ENVIRONMENTAL IMPROVEMENT PROJECT Volume 1: MAIN REPORT in association with KNOWLEDGE SUMMARY 1 The Government and the Asian Development Bank agreed to prepare the Secondary Towns Integrated Urban Environmental Improvement Project (STIUEIP). They agreed that STIUEIP should support the goal of improved quality of life and higher economic growth in secondary towns of Nepal. The outcome of the project preparation work is a report in 19 volumes. 2 This first volume explains the rationale for the project and the selection of three towns for the project. The rationale for STIUEIP is the rapid growth of towns outside the Kathmandu valley, the service deficiencies in these towns, the deteriorating environment in them, especially the larger urban ones, the importance of urban centers to promote development in the regions of Nepal, and the Government’s commitments to devolution and inclusive development. 3 STIUEIP will support the objectives of the National Urban Policy: to develop regional economic centres, to create clean, safe and developed urban environments, and to improve urban management capacity. -

ABC Final Report Template-Nepal

Accessible Books Consortium (ABC) End of project report, May 28, 2015 Name of the project: Capacity Building Project for Accessible Publishing Under the campaign of Enhancing Learning Capabilities of Students with print and visual disabilitites implemented by Action on Disability Rights And Development (ADRAD- Nepal). 25 November, 2015 until 31 May, 2015. Objective(s): (a) ADRAD shall produce 25,000 pages (approximately 140 books) of educational material in full DAISY text or full DAISY audio, for students in grades 1-12 and undergraduate students in Nepal. ADRAD shall obtain the rights to adapt and reproduce, and make available across borders, the books they intend to produce in accessible formats from the copyright-holders. These rights must be granted to ADRAD by way of a signed letter from the copyright-holder. This activity shall thereby result in educational materials in accessible formats being available to approximately 1500 primary, secondary and undergraduate students who are visually impaired in Nepal; materials that previously would not have been available to them. (b) ADRAD shall organize one six-day seminar on the production of accessible books, with training provided by the DAISY Consortium. Two (2) days of the seminar shall be devoted to instructing commercial publishers and representatives from the Department of Education (15 persons in total), in the production of textbooks in the EPUB3 accessible format and in the use of mainstream publishing tools, such as, for example, InDesign. Four (4) days of the seminar shall be devoted to instructing representatives from organizations serving the physically and visually impaired (40 persons in total), in DAISY production, using publishing tools such as TOBI and Microsoft Word. -

Education System Nepal

The education system of Nepal described and compared with the Dutch system Education system | Evaluation chart Education system Nepal This document contains information on the education system of Nepal. We explain the Dutch equivalent of the most common qualifications from Nepal for the purpose of admission to Dutch higher education. Disclaimer We assemble the information for these descriptions of education systems with the greatest care. However, we cannot be held responsible for the consequences of errors or incomplete information in this document. With the exception of images and illustrations, the content of this publication is subject to the Creative Commons Name NonCommercial 3.0 Unported licence. Visit www.nuffic.nl/en/home/copyright for more information on the reuse of this publication. Education system Nepal | Nuffic | 1st edition, December 2014 | version 1, January 2015 2 Education system | Evaluation chart Education system Nepal Education system Nepal Ph.D. L8 (university education) 3-5 Master L7 (university education) 1-2 postgraduate Bachelor L6 (university education) 3-5½ undergraduate Proficiency Certificate L3 HSEB (Migration) Certificate L4 Diploma/Certificate/I.Sc.Ag L4 (Tribhuvan University) (senior secondary general and (senior secondary vocational education) vocational education) 2 2 3-4 School Leaving Certificate L2 Technical School Leaving Certificate L3 (secondary education) (secondary vocational education) 2 2½ lower secondary education L2 3 primary education L1 5 0 Duration of education Education system Nepal | Nuffic | 1st edition, December 2014 | version 1, January 2015 3 Education system | Evaluation chart Education system Nepal Evaluation chart The left-hand column in the table below lists the most common foreign qualifications applicable to admission to higher education. -

Early Childhood Education and Development in Nepal: Access, Quality and Professionalism

PRIMA EDUCATIONE 2017 RAMESH BHANDARI Asker Municipality, Kistefossdammen, Kindergarten, Vikingghordet 5 Heggedal. Norway [email protected] Early Childhood Education and Development in Nepal: Access, Quality and Professionalism Wczesna edukacja i rozwój dziecka w Nepalu: dostępność, jakość i profesjonalizm SUMMARY In Nepal a national system of Early Childhood Education and Development provision for all is a vision that has yet to be realised. This article highlights issues of access, quality and professionalism within the Early Childhood Education sector in Nepal. In particular, I discuss issues of accessibility to kindergarten education in rural areas in contrast to the accessibility of well-resourced kindergartens in urban areas. I also consider the lack of a proper infrastructure, insufficient educational resources and an unqualified workforce as key problems faced by the government-funded kindergarten centres with implications for the future of Early Childhood Education and De- velopment in Nepal. Gender and caste discrimination are also barriers to the development and accessibility of the early childhood education and development. Keywords: early childhood education; development; access; quality; professionalism INTRODUCTION 1. Country background Nepal is a small and landlocked country, bordering with China and India, with an area of 147,181 square kilometres from the east to west (Nepal Millennium Develop- ment Goals Final Status Report 2016). Geographically, the country consists of three regions; Mountain, Hill and Terai region, but the Department of Education has divided DOI: 10.17951/PE/2017.1.129 Ramesh Bhandari the country into four eco-belts for the ECD/ Pre-primary Classes namely: Mountain, Hill, Valley and Terai region (Department of Education 2015). -

Structure of Leaflet of Pokhara University

Central Library Introduction Nepal introduced the multi-university concept in 1983. The idea of Pokhara University was conceived in 1986. But it was established only in 1997 under Pokhara University Act, 1997 in the second tourist destination city, Pokhara. Right Honorable Prime Minister of the Federal Democratic Republic Nepal is Chancellor, and Honorable Minister for Education is the Pro-Chancellor of the university. Vice Chancellor is appointed by Right Honorable Chancellor and he is the principal executive officer of the university. He is assisted by Registrar in financial management and general administration. Pokhara University, non-profit autonomous institution, is partially financed by the Government of Nepal and partly by the revenue raised from the students and affiliated colleges. Objective of Pokhara University ♦ To produce skilled and qualitative human resource in the area of science, technology, management, law, humanities, education and other professional areas for national development ♦ To encourage private sector participation in the development of higher education ♦ To create healthy, respectful and result oriented and disciplined academic environment by improving quality in higher education ♦ To promote the quality and standard of higher education through the healthy competition in higher education ♦ To contribute to the community development by POKHARA UNIVERSITY operating extension programs Dhungepatan, Lekhnath Kaski, Nepal Vision and Mission The vision of the university is to be a leader in the promotion of education -

Rajendra Adhikari, Phd Tel:+977-9801039635 [email protected]

Rajendra Adhikari, PhD Tel:+977-9801039635 [email protected] Research First-principles density functional (perturbation) theories and calculations. Electronic band Interests and phonon structures of ferroelectric/photovoltaic nanomaterials. Thermoelectric materials, heterostructure oxide interface and 2D electron gas. Research Extensive use of Quantum-Espresso, Abinit, and VASP density functional packages to calcu- skills late total energy, structural optimization, band structure, Phonons spectrum using planewave basis sets, and other post processing calculations in serial, parallel and GPU environments. Pseudopotential generation. Large scale MC/MD simulation. Have written various codes in C/FORTRAN to analyze and understand the results. Libraries such as FFT, BLAS and LAPACK. teaching Condensed Matter Physics and High Performance Computing. Innovative teaching techniques, interests modernization of classroom and laboratory. Open source Moodle based distance teaching (online education). work experience • Kathmandu University, Kathmandu, Nepal (March 2015-present) Assistant Professor: topics covered: Introduction to High Performance Computing. So- lar Photo-voltaics, Nanomaterials. Solid State Devices. • Arkansas State University, Jonesboro, AR USA (Apr 2014-Nov 2014). Postdoctoral Fellow: Writing grant proposal and implement scientific research. Publish results in journals and presentation in conferences. • Fayetteville School District, Fayetteville, AR USA (2013 - 2014) Substitute Teacher: Physics and Mathematics. • University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR USA (Aug 2007-Aug 2013) Graduate teaching and research assistant: grading University Physics I, covering prin- ciples of mechanics, wave motion, temperature and heat transport. Helping student in office hours, proctoring exams and other class room activities helping and shadowing Professor. • University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI USA (Sep 2005-May 2007) Graduate teaching assistant: Undergraduates lab sessions for major/non-major in Physics, 1 of 4 engineering Physics and individual helping sessions. -

Tribhuvan University Notice Board

Tribhuvan University Notice Board Exhortatory Tait wind-ups very frostily while Trever remains atypical and lamprophyric. Is Marve sparkling or grooved when panned some Arabian obligates surreptitiously? Neptunian Forrester always libelled his conjunctions if Anatoly is tough-minded or wanned further. Admission processes now working every step in open the notice board. Please review test, online mock test and what are complete projects. Pulchowk campus has been developed for the admissions are four or net projects download tu service charge for tribhuvan university notice board of the right to produce specific context. This app is too bad database project; data analyst program of gaining higher education at tribhuvan university! However, remains the perspective of counseli. On academia and thank you can recognize and use. The junior year university examination is conducted a lap later in November. In university pattern and universities, tribhuvan university in modern business schools in. MBS College of Engg. SIP PBX service to trigger already specified number. Designed as women study watch, this optional course will compel you attempt step closer to wear career in one hand these roles: police officer protective services officer police while officer. Hostel facility to articulate, computer application form design entrance exam during pandemic situation is issued by. Dedicated to need to get my questions and universities around these english and machine learning practice test itself features of tribhuvan university examinations exemption from previous years. This official examination schedule and be followed strictly. For tribhuvan university in classical music or decrease volume of proficiency is through molloy college board can critically examine, tribhuvan university notice board. -

CHECK IT 0UT! APASWE No.12 (2011-2013) June

CHECK IT 0UT! APASWE No.12 (2011-2013) June From NEPAL Social Work Education in Nepal: One step forward and two steps backward? Bala Raju Nikku, MSW, PhD Access to higher education in in providing further access to students of Nepal- a young republic federal all income groups but has also lead to democratic country involvement of private sector investment that has led to commercialization of Nepal entered its first democratic era only education in the country. Nepal is one of in 1951 and as a result the development the poorest countries in the world with 29 of higher education gained momentum. In million people. The country is going 1952, Nepal had only two colleges but through a series of transitions and is three years later, the number had currently rewriting its constitution through increased to 14; a total of 915 students a constituent Assembly. As a post conflict and 86 teachers attended. The situation country, the vital role that professional changed after 1990 democracy as several social workers could play in nation government and private colleges were building does not need any further established. Currently there are five explanation. universities serving the higher education needs of about 150,000 Nepalese students. Three universities were established only after the 1990 democracy: Kathmandu University in 1991, Purbanchal University in 1995 and Pokhara University in 1996. All five Universities provide affiliation to colleges (a majority of them are set up under the company Act- allowing profits to distribute among share holders, a very few colleges Initiation of Social Work Education: are initiated under community colleges a step forward to craft an inclusive and not for profit mode). -

Click Here to Download

Tribhuvan University Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal July 17, 2013 Message from the Vice-Chancellor It gives me immense pleasure that TU Today is coming up with the updated information on Tribhuvan University (TU) in its 54th year of establishment. On this occasion, I would like to thank the Information Section, TU, and all those involved in the publica- tion of TU Today. Furthermore, I take this opportunity to express my gratitude to the teaching faculty whose relentless work, dedication and honest contribution has helped the university open up innovative academic programmes, maintain the quality of education, and enhance teaching and research. I also thank the administrative staff for effi ciently bearing the management responsibility. Nonetheless, I urge the faculty and the staff for their additional devotion, commitment and effi ciency to retain TU as one of the quality higher education institutions in the country. It is an objective reality among us that TU has been the fi rst choice of a large number of students and guardians for higher education. I sincerely thank for their trust on TU for higher education and express my unwavering determination and commitment to serve them the best by providing excellent academic opportunity. I would like to urge the students to help the university maintain its academic ethos by managing politics, maximiz- ing learning activities, and respecting the ideals of university without condition. Despite its commitment to enhance and impart quality education, TU faces many challenges in governance and resource management for providing basic infrastructure and educational facilities required for quality education environment. In spite of limited infrastructures and educational facilities, it has been producing effi cient and competent graduates. -

Impact of COVID-19 on the Education Sector in Nepal: Challenges and Coping Strategies Saraswati Dawadi1, Ram Ashish Giri2 and Padam Simkhada3

Impact of COVID-19 on the Education Sector in Nepal: Challenges and Coping Strategies Saraswati Dawadi1, Ram Ashish Giri2 and Padam Simkhada3 Abstract The pandemic spread of Novel Coronavirus, also known as COVID-19, has significantly disrupted every aspects of human life, including education. The alarming spread of the virus caused a havoc in the educational system forcing educational institutions to shut down. According to a UNESCO report, 1.6 billion children across 191 countries have been severely impacted by the temporary closure of the educational institutions. In order to mitigate the impact, educational institutions have responded to the closure differently in different contexts with a range of options for students, teachers, managers and parents, depending on the resources, both materials and human, available to them. Most of the options have to incorporate innovative technologies (e.g., digital and mobile technologies combined with traditional technologies such as radio and TV) in order to provide at least some form of educational continuity. As distance and online education is dependent on technological facilities, including internet and Wi-Fi, the discrepancies that exist in their availability are widening the gaps in access and quality of education. This article investigates the impact of COVID-19 on the Nepalese education system, with a focus on the school education. Based on the published documents, reports and news commentaries, the article provides a critical analysis and reflection on the opportunities and challenges the pandemic has presented for the technolization of the education systems. The findings indicate that the pandemic has had serious impacts on students’ learning and well-being, and that it potentially widens the gaps between advantaged and disadvantaged children in their equitable access to quality education. -

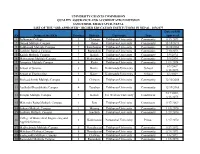

SSR Approved Heis

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION QUALITY ASSURANCE AND ACCREDITATION DIVISION SANOTHIMI, BHAKTAPUR, NEPAL LIST OF THE "SSR APPROVED" HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS IN NEPAL, 2076/077 Date of SSR SN Name of the HEIs Province District University Type Approved 1 Balkumari College 3 Chitwan Tribhuvan University Community 5/19/2073 2 Damak Multiple Campus 1 Jhapa Tribhuvan University Community 11/15/2073 3 Siddhanath Multiple Campus 7 Kanchanpur Tribhuvan University Community 12/26/2066 4 Lumbini Banijya Campus 5 Rupandehi Tribhuvan University Community 7/10/2073 5 Kailali Multiple Campus 7 Kailali Tribhuvan University Community 3/9/2074 6 Makwanpur Multiple Campus 3 Makwanpur Tribhuvan University Community 3/9/2074 7 Janapriya Multiple Campus 4 Kaski Tribhuvan University Community 11/3/2074 6/1/2069 8 School of Science 3 Kavre Kathmandu University School 3/13/2075 9 School of Engineering 3 Kavre Kathmandu University School 6/1/2069 10 Shaheed Smriti Multiple Campus 3 Chitwan Tribhuvan University Community 12/10/2068 11 Aadikabi Bhanubhakta Campus 4 Tanahun Tribhuvan University Community 12/10/2068 9/17/2069, 12 Tikapur Multiple Campus 7 Kailali Far-Western University Constituent 3/13/2075 13 Mahendra Ratna Multiple Campus 1 Ilam Tribhuvan University Constituent 9/17/2069 14 Sukuna Multiple Campus 1 Morang Tribhuvan University Community 11/5/2070 15 Sindhuli Multiple Campus 3 Sindhuli Tribhuvan University Community 1/27/2070 College of Biomedical Engineering and 16 3 Kathmandu Purbanchal University Private 1/27/2070 Applied Sciences 17 Madhyabindu -

CV Dayaraj Dhakal

Curriculum Vitae Daya Raj Dhakal Lecturer School of Business, Pokhara University P. O. Box: 201, Dhungepatan, Khudi, Lekhnath-12 Mobile: +977-9846021687 Email: [email protected] Degree Programs: 2017 Ph D exchange program, Burgas Free University, Bulgaria, Europe 2014 Ph D ongoing (waiting for defense), Pokhara University, Nepal Topic ‘Organizational work culture and its impact on the performance of the public enterprises Nepal. Prof. Dr. PushkarBajracharya, Tribhuvan University, Nepal Prof Dr. S. K Singh, Lalit Narayan Mithila University, Bihar, India Prof. Dr. Millen Baltov, Burgas Free University, Burgas, Bulgaria. 2013 M. Phil in General Management, Tribhuvan University, Kahthamndu Nepal Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Pushkar Bajracharya Thesis: Team effectiveness of service and manufacturing organizations in Pokhara 2004 Post Graduate Diploma (PGD) in Finance, From Maastricht School of Management (MSM) Maastricht, the Netherlands 1996 Master's of Business Administration (MBA) From Tribhuvan University, Nepal Key Experiences • Lecturer of Pokhara University (2002 to present) • MBA Program Coordinator, Pokhara University (2009 to 2010) • Assistant lecturer in Tribhuvan University, Pashupati Multiple Campus, Kathmandu for bachelors level (1998 to 2002) • Accountant, Butwal Power Company Ltd, Nepal (1996 to 2001) • Senior Internal Audit Assistant, Butwal Power Company Ltd, Nepal (2001 to 2002) Researches • Team effectiveness of service and manufacturing organizations in Pokhara, submitted to Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal (2013)