Final Local Administration in Cyprus 1 REVIEWED JJ-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyprus Tourism Organisation Offices 108 - 112

CYPRUS 10000 years of history and civilisation CONTENTS CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 CYPRUS 10000 years of history and civilisation 6 THE HISTORY OF CYPRUS 8200 - 1050 BC Prehistoric Age 7 1050 - 480 BC Historic Times: Geometric and Archaic Periods 8 480 BC - 330 AD Classical, Hellenistic and Roman Periods 9 330 - 1191 AD Byzantine Period 10 - 11 1192 - 1489 AD Frankish Period 12 1489 - 1571 AD The Venetians in Cyprus 13 1571 - 1878 AD Cyprus becomes part of the Ottoman Empire 14 1878 - 1960 AD British rule 15 1960 - today The Cyprus Republic, the Turkish invasion, 16 European Union entry LEFKOSIA (NICOSIA) 17 - 36 LEMESOS (LIMASSOL) 37 - 54 LARNAKA 55 - 68 PAFOS 69 - 84 AMMOCHOSTOS (FAMAGUSTA) 85 - 90 TROODOS 91 - 103 ROUTES Byzantine route, Aphrodite Cultural Route 104 - 105 MAP OF CYPRUS 106 - 107 CYPRUS TOURISM ORGANISATION OFFICES 108 - 112 3 LEFKOSIA - NICOSIA LEMESOS - LIMASSOL LARNAKA PAFOS AMMOCHOSTOS - FAMAGUSTA TROODOS 4 INTRODUCTION Cyprus is a small country with a long history and a rich culture. It is not surprising that UNESCO included the Pafos antiquities, Choirokoitia and ten of the Byzantine period churches of Troodos in its list of World Heritage Sites. The aim of this publication is to help visitors discover the cultural heritage of Cyprus. The qualified personnel at any Information Office of the Cyprus Tourism Organisation (CTO) is happy to help organise your visit in the best possible way. Parallel to answering questions and enquiries, the Cyprus Tourism Organisation provides, free of charge, a wide range of publications, maps and other information material. Additional information is available at the CTO website: www.visitcyprus.com It is an unfortunate reality that a large part of the island’s cultural heritage has since July 1974 been under Turkish occupation. -

SUPPLEMENT No. 3 Το the CYPRUS GAZETTE No. 3648 of .15TH OCTOBER, 1952

SUPPLEMENT No. 3 το THE CYPRUS GAZETTE No. 3648 OF .15TH OCTOBER, 1952. SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION. No. 449. THE ELEMENTARY EDUCATION LAW. CAP. 203 AND LAWS 22 OF 1950 AND 17 OF 1952. ORDER MADE UNDER SECTION 73. A. B. WRIGHT, Governor. Whereas-on the report of the Director of Education it appears to me that it is desirable to compel the Town Committees and Village Commissions for the Greek-Orthodox Schools of the towns and villages mentioned in the first column of the Schedule hereto (hereinafter referred to as " the Committees arid Commissions "), in their respective towns and villages, to provide, erect, repair, extend, improve or develop the school buildings, premises, playgrounds, yards, gardens or teachers' dwellings, as the case may be, particulars whereof are given in the second column of the said Schedule (hereinafter referred to as " the premises "): Now, therefore, in exercise of the powers vested in me by section 73 of the Cap. 203 z Elementary Education Law, I, the Governor, do hereby order that the * °^ *95o Committees and Commissions shall in their respective towns or villages provide, erect, repair, extend, improve or develop the premises. SCHEDULE. Nicosia District. Town or village. Particulars. Argaki Extension of, the school building. Astromeritis · .. Repairs to the school building. Evrykhou .. .. Repairs to the school building. Kaimakli Repairs to the Girls' School. Kalopanayiotis Repairs to the school premises. Karavostasi-Xeros Repairs to the school latrines. Khrysidha Erection of new school. Lakatamia, Pano and Kato Repairs to the teachers' dwellings. Latsia Repairs to the school premises. Loutros Erection of a teacher's dwelling and repairs to the school building. -

Acs Courier Network (Cyprus)

4.2021 ACS COURIER NETWORK (CYPRUS) SERVICE POINT AREA ADDRESS TELEPHONE OPENING HOURS City Centre - N8 1C Evagorou Ave & An.Leventi, 1097 Nicosia 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 8:45-18:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Michalakopoulou - N3 22 Michalacopoulou Str, 1075 Nicosia 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Strovolos - N2 70 Athalassas Ave, 2012 Strovolos 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Engomi - EG 34B October 28th Str, 2414 Engomi 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Lakatamia - LK 40H Makariou Ave, 2324 Lakatamia 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Strakka - N9 351 Arch. Makariou III, 2313 Pano Lakatamia 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-18:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Pallouriotisa - N6 68A John Kennedy Ave, 1046 Pallouriotisa 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-18:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Pera Chorio Nisou- PR 27C Makariou Ave, 2572 Pera Chorio Nisou 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-18:00 Sat: 8:45-13:00 Strovolos Ind.Area - N5 14 Varkizas Str, 2033 Strovolos Ind. Area 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 07:45 - 19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 NICOSIA Latsia - LA 33 Arch. Makariou Ave, 2220 Latsia 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Kokkinotrimithia - KR 2 Gr. Auxentiou & Avlonos 2660 Kokkinotrimithia 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-18:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Astromeritis - N7 70A Grivas Digenis Ave, 2722 Astromeritis 99 465150 Mon-Fri 10:00 - 19:00 Sat 08:00-13:00 Soleas area- SL 47 Makariou Str, 2800 Kakopetria 22 922219 Mon-Fri 10:30-13:00+15:15-17:30 Wed + Sat 10:30-13:00 Ergates - ER 2 Meg.Alexandrou, 2643 Ergates 22 515155 Mon-Fri 9:00-18:00 Wed + Sat 9:00-14:00 Tsireio - L4 41 Stelios Kyriakides Str, 3080 Limassol 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Agios Nicolaos - L2 3 Riga Feraiou Str, 3095 Limassol 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Omonoia - ΟΜ 35A Vasileos Pavlou Str, 3052 Limassol 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Kolonakiou - LF 17 Sp. -

Authentisch Route 1

Zypern Authentisch Route 1 Sicherheit Autofahren in Zypern Nur Gemütliche DIGITALE Unterkünfte auf dem Land Ausgabe Tipps Nützliche Informationen Erforschen Sie den Ostteil Zyperns Agia Napa – Kap Greco – Protaras – Paralimni – Deryneia – Frenaros – Avgorou – Die Grüne Linie Entlang (Überquerung nahe Achna) – Xylotymvou – Ormideia – Xylofagou – Liopetri – Agia Napa Route 1 Agia Napa – Kap Greco – Protaras – Paralimni – Deryneia – Frenaros – Avgorou – Die Grüne Linie Entlang (Überquerung nahe Achna) – Xylotymvou – Ormideia – Xylofagou – Liopetri – Agia Napa Milia Arnadi Spathariko Pigi Santalaris Aloda Peristerona Agios Maratha M E S A O R I A Limnia Sergios Salamis Pyrga Apostolos Prastio Varnavas Stylloi Egkomi AMMOCHOSTOS BAY Gaidouras Engkomi Tumulus AMMOCHOSTOS Kouklia (FAMAGUSTA) Acheritou Kalopsida Makrasyka Deryneia Achna Dam Frenaros Paralimni Avgorou Achna Sotira Pernera Xylotymvou Neolithic Liopetri Protaras Settlement Ε4 Agia Ormideia Agia Napa Napa Potamos Xylofagou Liopetriou Cape Gkreko Cape Pyla LARNAKA BAY scale 1:300,000 0 1 2 4 6 8 10 Kilometers KERYNEIA Prepared by Lands and Surveys Department, Ministry of Interior, Kypros 2015. RLegendeeference AMMOCHOSTOS AutobahnMotorway NaturpfadeNatural Tr a(Start)ils (Start of) HauptstraßeMain Road PicknickplätzePicnic Sites NebenstraßeSeconary R oad LeuchtturmLighthous e LARNAKA EuropäischerEuropean L oFernwanderwegng distance E4 ArchäologischeArchaeologica Stättel Sites path E4 NaturpfadNatureTrail KircheChurch BezirksgrenzeDistrict Boundary KlosterMonastery SouveränerBritish -

Cyprus Information Guide Republic of Cyprus Ministry of Interior European Union

CYPRUS INFORMATION GUIDE REPUBLIC OF CYPRUS MINISTRY OF INTERIOR EUROPEAN UNION Action co-funded by the European Integration Fund ΑΛΛΗΛΕΓΓΥΗ, ΠΡΟΟΔΟΣ, ΕΥΗΜΕΡΙΑ - SOLIDARITY, PROGRESS, PROSPERITY This publication was prepared by INNOVADE LI LTD and CARDET LTD, as part of the project with title “Updated General Information Guide about Cyprus ” [Action A4, European Integration Fund for the Third Country Nationals, Annual Programme 2013]. The Action was co-financed by the European Integration Fund for Third Country Nationals (95%) and the Republic of Cyprus (5%). Copyright © 2015 by the Solidarity Funds Sector, Ministry of Interior, Republic of Cyprus. This publication may be reproduced only for non-commercial purposes, and full reference should be provided to the original source. www.cyprus-guide.org ISBN 978-9963-33-886-3 Cyprus Information Guide The Guide is developed under the project: Update of the Guide with General Information about Cyprus (Action A4, European Integration Fund for Third Country Nationals, Annual Programme 2013). This Guide was developed for information purposes only and no rights can be derived from its contents. The project partners did their best to include accurate, corroborated, transparent, and up-to-date information, but make no warrants as to its accuracy or completeness. The information contained in the Cyprus Information Guide has been gathered from reliable sources such as the Cyprus Tourism Organisation, the Press and Information Office, Ministries, Public Authorities and non-governmental organisations. Any information contained herein is subject to change without notice. All information available in this Guide was validated during the period of March – April 2015. Readers shall therefore cross-check the accuracy of the information provided in this Guide with the relevant authorities. -

Table of Contents

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT GROUP C – FAMAGUSTA AREA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. CONTRACT FOR ENGINEERING SERVICES.....................................................................................1 1.2. PURPOSE OF STUDY ...................................................................................................................2 2. INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK FOR EIA............................................................................................ 3 2.1. ENVIRONMENTAL ORGANISATION IN CYPRUS...............................................................................3 2.1.1. CENTRAL GOVERNMENT LEVEL............................................................................................3 2.1.2. LOCAL LEVEL......................................................................................................................4 2.1.3. NON GOVERNMENTAL ORGANISATIONS ................................................................................5 2.2. CYPRUS NATIONAL LAW 57(I)/2001 ON EIA ................................................................................5 2.2.1. OBLIGATION FOR EIA STUDY................................................................................................5 2.2.2. CYPRUS NATIONAL LAW 57(I)/2002 ON EIA.........................................................................5 2.3. OTHER NATIONAL LAWS .............................................................................................................6 -

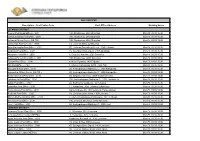

DISCLOSURE - GENESIS PHARMA (CYPRUS) LTD 2019 Date of Publication: 30/06/2020

DISCLOSURE - GENESIS PHARMA (CYPRUS) LTD 2019 Date of publication: 30/06/2020 HCPs: City of Principal Practice Country of Principal Unique country Fee for service and consultancy (Art. Full Name Principal Practice Address Contribution to costs of Events (Art. 3.01.1.b & 3.01.2.a) HCOs: city where Practice identifier OPTIONAL 3.01.1.c & 3.01.2.c) registered Donations and Related expenses TOTAL Grants to HCOs agreed in the fee for OPTIONAL (Art. 3.01.1.a) Sponsorship service or agreements with consultancy Travel & (Art. 1.01) (Art. 3) (Schedule 1) (Art. 3) (Art. 3) HCOs / third parties Registration Fees Fees contract, including Accommodation appointed by HCOs travel & to manage an Event accommodation relevant to the contract INDIVIDUAL NAMED DISCLOSURE - one line per HCP (i.e. all transfers of value during a year for an individual HCP will be summed up: itemization should be available for the individual Recipient or public authorities' consultation only, as appropriate) 6 International Airport Dr. Pantzaris Marios Nicosia Cyprus Ave.,Ayios Dhometios, 3179 N/A N/A € 690.00 € 1,674.60 € 1,040.00 € 0.00 € 3,404.60 2370 Nicosia 9, Konstantinou Mourouzi, Dr. Koukoullis Limassol Cyprus Mesa Geitonia, 4001 2207 N/A N/A € 838.75 € 0.00 € 0.00 € 0.00 € 838.75 Roumiana Limassol The Cyprus Instidute of Neurology and Genetics, 6 Dr Leonidou Eleni Nicosia Cyprus Aerodromiou Avenue, 3241 N/A N/A € 690.00 € 1,674.60 € 1,040.00 € 0.00 € 3,404.60 2370, Ayios Dometios, Nicosia 55-57 Andrea Avraamides, Dr Panayiotou Nicosia Cyprus Strovolos, 2024 Nicosia, 2943 N/A N/A € 730.00 € 1,674.60 € 1,040.00 € 0.00 € 3,444.60 Panayiotis Cyprus Dr Petsa Koumidiou 79, G. -

Cost Center Code Post Office Address Working Hours LEFKOSIA

POST OFFICES Description - Cost Center Code Post Office Address Working Hours LEFKOSIA DISTRICT Cyprus Post Head Offices - 1001 100, Prodromou, 2063 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Lefkosia District Post Office - 2000 100, Prodromou, 2063 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Lefkosia Citizen Center (KE.PO.) 100, Prodromou, 2063 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Latsia Mail Sorting Center - 8000 13, Leoforos Kilkis, 2234 Latsia Agioi Omologitai Post Office - 2030 55, Leoforos Dimostheni Severi, 1080 Lefkosia Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Aglantzia Post Office - 2120 16, Georgiou Griva Digeni, 2108 Aglantzia Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Akropolis Post Office - 2050 4, Grigoriou Karekla, 2023 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Lefkosia Parcels Post Office - 2001 100, Prodromou, 2063 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Egkomi Post Office - 2090 4, Neas Egkomis, 2409 Egkomi Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Dali Post Office - 2140 Leoforos Chalkanoros 56DE, 2540 Dali Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Kakopetria Post Office - 2130 20, Archiepiskopou Makariou C', 2800 Kakopetria Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Kakopetria Citizen Center (KE.PO.) 20, Archiepiskopou Makariou C', 2800 Kakopetria Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Kokkinotrimithia Post Office - 2190 59, Grigoriou Afxentiou, 2660 Kokkinotrimithia Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Lakatameia Post Office - 2150 256, Archiepiskopou Makariou C', 2311 Lakatameia Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Latsia Post Office - 2160 20, Eleftheriou Venizelou, 2235 Latsia Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Lykavittos Post Office - 2080 14, Kallipoleos, 1055 Lefkosia (Lykavittos) Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Pallouriotissa Post Office -

S/2017/1008 Security Council

United Nations S/2017/1008 Security Council Distr.: General 28 November 2017 Original: English Strategic review of the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 2369 (2017), in which the Council requested a strategic review of the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) focused on findings and recommendations for how UNFICYP should be optimally configured to implement its existing mandate, based exclusively on a rigorous evidence-based assessment of the impact of UNFICYP activities. 2. In line with the request of the Security Council, the review focused on an assessment of the key functions, tasks, and activities of UNFICYP, and their respective impact. At the same time, the review assessed the Force’s existing capacity and capabilities in an effort to ensure that it would be optimally configured to fulfil its mandated tasks. II. Methodology 3. The strategic review was led by an external expert, Wolfgang Weisbrod-Weber, former Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Western Sahara. Mr. Weisbrod-Weber was supported by a review team consisting of representatives from the Departments of Peacekeeping Operations, Field Support, Political Affairs and Safety and Security of the Secretariat, as well as staff of UNFICYP. 4. The UNFICYP review process was conducted in three stages. First, consultations were undertaken, at both Headquarters and UNFICYP, with relevant stakeholders, including representatives of the Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot communities and of the Member States concerned, on the proposed objectives, methodology and timeline of the strategic review. -

Implementation of Sewerage Systems in Cyprus

MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE , NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT Monitoring of the Implementation Plan in Cyprus Current Status Dr. Dinos A. Poullis Executive Engineer Water Development Department Ministry of Agriculture Natural Resources and Environment Contents Accession Treaty Commitments National Implementation Plan Stakeholders in the Implementation Plan Sewerage Boards Organizational Setup Information and Data Sources for the Preparation of the Implementaton Plan Implementation – current status Work to be Done Difficulties in Implementation Concluding Remarks Accession Treaty Commitments Transitional period negotiated in the accession treaty of Cyprus for the implementation of the UWWTD, Articles 3, 4 and 5(2) ◦ 31.12.2012 Three interim deadlines concerning four agglomerations>15.000pe ◦ 31.12.2008 – 2 agglomerations (Limassol and Paralimni) ◦ 31.12.2009 - 1 agglomeration (Nicosia) ◦ 31.12.2011 - 1 agglomeration (Paphos) National Implementation Plan National Implementation Plan2005 ◦ Submitted to the EC in March 2005 ◦ 6 Urban agglomerations – 545.000pe ◦ 36 Rural agglomerations – 130.000pe National Implementation Plan2008 ◦ Working Groups for Reporting and the EC Guidance Document ◦ Revised NIP-2008 (agglomeration methodology, new technical solutions, government policies and law amendments) ◦ 7 Urban agglomerations – 630.000pe ◦ 50 Rural agglomerations – 230.000pe Article 17 ◦ A revised Implementation Plan is under preparation. Stakeholders in the Implementation Plan Council of Ministers (overall responsibility for the Implementation Plan) Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment Ministry of Interior Ministry of Finance Planning Bureau Sewerage Boards (Established and operate under the “Sewerage Systems Laws 1971 to 2004”) ◦ Urban Sewerage Boards ◦ Rural Sewerage Boards Sewerage Boards Organizational Setup Urban Sewerage Boards ◦ Autonomous organizations (technically and administratively competent) ◦ Carry out their own design, tendering, construction and operation of their sewerage systems. -

Communism and Nationalism in Postwar Cyprus, 1945-1955

Communism and Nationalism in Postwar Cyprus, 1945-1955 Politics and Ideologies Under British Rule Alexios Alecou Communism and Nationalism in Postwar Cyprus, 1945-1955 Alexios Alecou Communism and Nationalism in Postwar Cyprus, 1945-1955 Politics and Ideologies Under British Rule Alexios Alecou University of London London , UK ISBN 978-3-319-29208-3 ISBN 978-3-319-29209-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-29209-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016943796 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the pub- lisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

ENERGY ACTION PLAN Latsia Municipality - Cyprus

ENERGY ACTION PLAN Latsia Municipality - Cyprus ENERGY ACTION PLAN LATSIA MUNICIPALITY CYPRUS 22 November 2011 Cyprus Energy Agency – Ενεργειακό Γραφείο Κυπρίων Πολιτών 1 ENERGY ACTION PLAN Latsia Municipality - Cyprus Brief Summary The “Pact of Islands” (ISLE-PACT project) is committed to developing Local Energy Action Plans, with the aim of achieving European sustainability objectives as set by the EU for 2020, that is of reducing CO2 emissions by at least 20% through measures that promote renewable energy, energy saving and sustainable transport. The Cyprus Energy Agency is a participating partner in the ISLE-PACT project and has invited Cyprus local authorities to demonstrate their political commitment by signing the “The Pact of Islands”; agreement in order to achieve the EU sustainability targets for 2020. Latsia is district of Nicosia is an independent municipality and from 23 February 1986. It is 7 km from Nicosia, is located at an altitude of 190 meters and covers an area of 16.28 sq km. The population of the municipality amounts to 13,000 inhabitants. The year 2009 was designated as the reference year / recording of energy consumption and CO2 emissions in the City. According to actual consumption data collected by the Electricity Authority of Cyprus, the oil companies, etc. Statistical Service of Cyprus total energy consumption in Latsia 2009 was 357.849 MWh. The largest consumer of energy in the municipality is the transport 190.525 MWh, then the tertiary sector with 77.276 MWh. The CO2 emissions in 2009 attributable to the overall energy consumption in the municipality are 153.557 tons.