A Case Study of Recent Immigrants to Colchester County, Nova Scotia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archibald Descendants

Archibald Descendants by James Clifford Retson Last Revised September 11 2020 Outline Descendant Report for John Archibald 1 John Archibald b: 30 Dec 1650 in Kennoway Paroch, Fife Scotland, d: 15 Nov 1728 in East Derry, (Londonderry),New Hampshire, USA + Jane Janet Tullock b: 1654 in Clackmannan, Clackmannanshire, Scotland, d: 15 Nov 1728 in Londonderry, Londonderry, Ireland ...2 Robert J (Gilleasbaig) Archibald b: 1668 in Machra Parish, Londonderry, Ulster, Ireland, d: Apr 1765 in Londonderry, Rockingham, New Hampshire, USA + Ann Boyd b: 1668 in Londonderry, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom, m: 1693 in Londonderry, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom, d: 1765 in Londonderry, New Hampshire, USA ......3 John Major Archibald b: 1693 in Maghera, Londonderry, Ireland; Age on gravestone given as 58, d: 10 Aug 1751 in East Derry, Londonderry ,New Hampshire, USA; Age on gravestone given as 58 + Margaret Wilson b: 1700 in Londonderry, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland, m: Abt 1715 in Londonderry, Rockingham, New Hampshire, USA; Alternative 1716 Ireland, d: Aft. 1751 in Londonderry, Rockingham, New Hampshire, USA .........4 David Archibald Esq. b: 20 Sep 1717 in Maghera, Londonderry, Ireland, d: 09 Nov 1797 in Truro, Colchester County, Nova Scotia, Canada + Elizabeth Elliott b: 10 Jun 1720 in Londonderry,Derry,North Ireland, m: 19 May 1741 in Londonderry, NH, New England, USA, d: 19 Oct 1791 in Truro Township, Nova Scotia ............5 Samuel Archibald b: 11 Nov 1742 in Parish of Maghra [Maghera] Couny Londonderry, Ireland, d: 15 Feb 1780 in Nevis, West Indies + Rachel Todd Duncan b: Abt 1743 in Londonderry, New Hampshire, USA, m: Truro Township, Colchester County, NS. -

Town Council Meeting January 22, 2019 6:30 P.M

Town Council Meeting January 22, 2019 6:30 p.m. Council Chambers, Town Hall 359 Main Street Agenda Call to Order 1. Approval of Agenda 2. Approval of Minutes a. Town Council Meeting, December 11, 2018 3. Comments from the Mayor 4. Public Input / Question Period Procedure: A thirty-minute time period will be provided for members of the public to address Council regarding questions, concerns and/or ideas. Each person will have a maximum of two minutes to address Council with a second two-minute time period provided if there is time within the thirty-minute Public Input / Question timeframe. 5. Motions/Recommendations from Committee of the Whole, January 8, 2019: a. RFD 084-2018: Climate Change and Energy Staffing b. RFD 077-2018: Hospitality Policy 359 Main Street | Wolfville | NS | B4P 1A1 | t 902-542-5767 | f 902-542-4789 Wolfville.ca 6. Correspondence: a. Email from June Pardy – RE: Open for Business b. Email from Jeff Hennessy – RE: Church Brewery c. Email from Kristin Harris – RE: Church Brewery d. NSFM Board Initiatives e. Email from Glen Pavelich: Turbine Power f. Email from Drew Redden – RE: Church Brewery g. Email from Paige Hoveling – RE: DDT for first time buyers h. Email from David Daniels – RE: Church Brewery i. Email from Jeff Hennessy – RE: CoW Meeting j. Email from Michael Bawtree – RE: December 2018 Newsletter k. Email from Dick Groot – RE: Facts from a brewer l. Email from Erin Pilcher – RE: Slippery Sidewalks m. Email from Stephen Drahos – RE: Accessory Use n. Email from Sam Corbeil – RE: Brewing Project o. -

Farmworks Shareholders

FarmWorks Shareholders 29-Feb-16 David Aalders 73 Coronation Street Halifax B3N 2M7 15-Jan-15 Lely Abud 21 Whitetail Lane Maders Cove B0J 2E0 1-Mar-12 Pamela Ackerman 16 Little Brook Lane Wolfville B4P 1X5 30-May-17 Pamela Ackerman 16 Little Brook Lane Wolfvile B4P 1X6 28-Feb-17 Barbara Jean Aikman 1869 Melanson Road Wolfville B4P 2R1 1-Mar-12 Ann Anderson 27 Pleasant Street Wolfville B4P 1M6 1-Mar-13 Ann Anderson 27 Pleasant Street Wolfville B4P 1M6 1-Mar-14 Ann Anderson 27 Pleasant Street Wolfville B4P 1M6 15-Jan-15 Ann Anderson 27 Pleasant Street Wolfville B4P 1M6 2-Mar-15 Ann Anderson 27 Pleasant Street Wolfville B4P 1M6 29-Feb-16 Ann Anderson 27 Pleasant Street Wolfville B4P 1M6 28-Feb-17 Ann Anderson 27 Pleasant Street Wolfville B4P 1M6 1-Mar-12 Barbara J Anderson 31 Bishop Avenue Wolfville B4P 2L4 1-Mar-12 Kerri Anderson 525 Main Street Kentville B4N 1L4 1-Mar-13 Kerri Anderson 525 Main Street Kentville B4N 1L4 1-Mar-14 Kerri Anderson 525 Main Street Kentville B4N 1L4 2-Mar-15 Stephen O Anderson 1071 Ridge Road RR1 Wolfville B4P 2R1 1-Mar-12 Stephen O Anderson 1071 Ridge Road RR1 Wolfville B4P 2R1 1-Mar-13 Stephen O Anderson 1071 Ridge Road RR1 Wolfville B4P 2R1 1-Mar-14 Stephen O Anderson 1071 Ridge Road RR1 Wolfville B4P 2R1 28-Feb-17 Stephen O Anderson 1071 Ridge Road RR1 Wolfville B4P 2R1 2-Mar-15 Kathryn J Anderson 199 Loop Highway 6 Tatamagouche B0K 1V0 1-Mar-12 Geoff Appleby 99 Lakemist Court Dartmouth B3A 4Z1 1-Mar-14 Shannon Archibald 122A Hawthorne Street Antigonish B2G 1A9 29-Feb-16 Roberto Armenta 23 Cranston Avenue Dartmouth B2Y 3G1 1-Mar-14 Christopher R Atwood 1443 Highway #1 Wellington Yarmouth B5A 4A5 2-Mar-15 Christopher R Atwood 1443 Highway #1 Wellington Yarmouth B5A 4A5 28-Feb-17 Christopher R. -

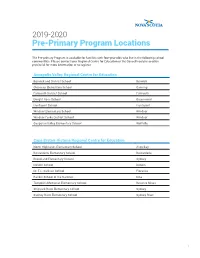

2019-2020 Pre-Primary Program Locations

2019-2020 Pre-Primary Program Locations The Pre-primary Program is available for families with four-year-olds who live in the following school communities. Please contact your Regional Centre for Education or the Conseil scolaire acadien provincial for more information or to register. Annapolis Valley Regional Centre for Education Berwick and District School Berwick Glooscap Elementary School Canning Falmouth District School Falmouth Dwight Ross School Greenwood Hantsport School Hantsport Windsor Elementary School Windsor Windsor Forks District School Windsor Gasperau Valley Elementary School Wolfville Cape Breton-Victoria Regional Centre for Education North Highlands Elementary School Aspy Bay Boularderie Elementary School Boularderie Brookland Elementary School Sydney Donkin School Donkin Dr. T.L. Sullivan School Florence Rankin School of the Narrows Iona Tompkins Memorial Elementary School Reserve Mines Shipyard River Elementary School Sydney Sydney River Elementary School Sydney River 1 Chignecto-Central Regional Centre for Education West Colchester Consolidated School Bass River Cumberland North Academy Brookdale Great Village Elementary School Great Village Uniacke District School Mount Uniacke A.G. Baillie Memorial School New Glasgow Cobequid District Elementary School Noel Parrsboro Regional Elementary School Parrsboro Salt Springs Elementary School Pictou West Pictou Consolidated School Pictou Scotsburn Elementary School Scotsburn Tatamagouche Elementary School Tatamagouche Halifax Regional Centre for Education Sunnyside Elementary School Bedford Alderney Elementary School Dartmouth Caldwell Road Elementary School Dartmouth Hawthorn Elementary School Dartmouth John MacNeil Elementary School Dartmouth Mount Edward Elementary School Dartmouth Robert K. Turner Elementary School Dartmouth Tallahassee Community School Eastern Passage Oldfield Consolidated School Enfield Burton Ettinger Elementary School Halifax Duc d’Anville Elementary School Halifax Elizabeth Sutherland Halifax LeMarchant-St. -

Acadia Archives |

/ .r / FALL CONVOCATION FOUNDERS' DAY ACADIA UNIVERSITY 10:00 A.M. SATURDAY, OCTOBER 28 1972 WOLFVILLE, NOVA SCOTIA PROCESSIONAL 0 CANADA WELCOME HY DR. J. M. R. BEVERIDGE, PRESIDENT AND VICE-CHANCELLOR LA YING OF WREATHS PRAYER OF INVOCATION PRESENTATION OF ALUMNI SCHOLARSHIPS CONVOCATION FOR AWARDING OF DEGREES AND DIPLOMAS PRESIDING: DR. CHARLES B. HUGGINS, CHANCELLOR POSTGRADUATE DEGREES Master of Arts Bishop, Barbara Evelyn Leonard (English) ... .........Paradise, N.S. Wilson, Edgar Mordante (English) ........................................ Guyana Master of Science Brumbaugh, Ray Kent (Psychology) .......................... Lancaster, Pa. Haight, Caleb Barry (Mathematics) .................... North Range, N.S. Huston, Frank (Biology) ................................................ Wolfville, N.S. Schaffner, John Phinney (Chemistry) ...................... Kentville, N.S. Master of Education Atkinson, Sylvester James......... ...........................Stoney Island, NS. Grant, Frederick William.. ......... ..... .......... .................... Moncton, N.B. Hache, Alfred .................................................................. Lunenburg, N.S. Hughes, Andrew Samuel.. ..... ......................................... Wolfville, N.S. Johnston, Brian Earl......................... ......................... ...... Wolfville, N.S. Lindsay, Arthur John .............. .. ........... ................. Tatamagouche, N.S. Neve, Peter Emerson............. ........................................... St. Flore, P.Q. Steeves, Lawson Starrak. -

Kekina'muek: Learning About the Mi'kmaq of Nova Scotia

Kekina’muek (learning) Timelog Learning about the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia transfer from QXD to INDD 3 hours to date-- -ha ha ha....like 50 min per chapter (total..8-10 hours) Edits from hard copy: 2 hour ro date Compile list of missing bits 2 hours Entry of missing stuff pick up disk at EWP .5 hr Table of Contents Entry from Disk (key dates) March 26 Acknowledgements................................................. ii mtg with Tim for assigning tasks .5 hr March 28 Introduction ......................................................iii research (e-mail for missing bits), and replies 45 min How to use this Manual .............................................iv MARCH 29 Text edits & Prep for Draft #1 4.5 hours Chapter 1 — The Story Begins ........................................1 March 30 Finish edits (9am-1pm) 2.0 Chapter 2 — Meet the Mi’kmaq of Yesterday and Today .................... 11 Print DRAFT #1 (at EWP) 1.0 Chapter 3 — From Legends to Modern Media............................ 19 research from Misel and Gerald (visit) 1.0 April 2-4 Chapter 4 — The Evolution of Mi’kmaw Education......................... 27 Biblio page compile and check 2.5 Chapter 5 — The Challenge of Identity ................................. 41 Calls to Lewis, Mise’l etc 1.0 April 5 Chapter 6 — Mi’kmaw Spirituality & Organized Religion . 49 Writing Weir info & send to Roger Lewis 1.5 Chapter 7 — Entertainment and Recreation.............................. 57 April 7 Education page (open 4 files fom Misel) 45 min Chapter 8 — A Oneness with Nature ..................................65 Apr 8 Chapter 9 — Governing a Nation.....................................73 General Round #2 edits, e-mails (pp i to 36 12 noon to 5 pm) 5 hours Chapter 10 — Freedom, Dependence & Nation Building ................... -

Sept.2009.Pdf

onthe PREMIER EDITION FALL 2009 HORIZON The Horizons Community Development Associates Newsletter In this issue... Welcome... Welcome to the first edition of our newsletter! INTRODUCTION 1 mentary skills and interests, and seek contracts At our annual fall retreat in September, we couldn’t do without each other. This is a we talked about how we can keep all the visionary and passionate group with excellent ideas and connections, and we usually enjoy CURRENT CONTRACTS 2 people we work with engaged on an delicious food when we get together. ongoing basis between contracts, and how WHAT’S HAPPENING? 3 we can strengthen our existing excellent Our Circle members are: Barbara Kaizer relationships within the Horizons team – (Grand Pré), Darcy Santor (Ottawa), Joanne and the newsletter idea was born! At this Linzey (Canning), and John Colton (Wolfville). CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE 4 point we are envisioning it as quarterly, and COMMUNITY Research Assistants (RAs) we intend to circulate it electronically to everyone we work with regularly. Our pool of RAs have a broad range of CALENDAR OF EVENTS 5 skills and interests, and work on a casual basis on all kinds of contracts. The RAs are We want to use the newsletter to keep all of you an incredibly talented, wise, and kind group of ON A PERSONAL NOTE… 5 informed about the contracts we are working on, people, and we have fun working together. and about relevant events and resources, and we also want to use it as a tool for everyone to Our RAs are Barbara Lipp (Aylesford), IN THE KNOW 6 get to know each other. -

Coastal Area Management in Nova Scotia: Building Awareness at the Municipal Level

Coastal Area Management in Nova Scotia: Building Awareness at the Municipal Level Prepared by Corey Toews Rural Communities Impacting Policy Student Intern November 2005 Coastal Area Management in Nova Scotia: Building Awareness at the Municipal Level Prepared by Corey Toews Rural Communities Impacting Policy Student Intern Prepared for The Atlantic Health Promotion Research Centre at Dalhousie University and The Coastal Communities Network of Nova Scotia - partners in the The Rural Communities Impacting Policy (RCIP) Project November 2005 The mission of the Atlantic Health Promotion Research Centre is to conduct and facilitate health promotion research that influences policy and contributes to the health and well-being of Atlantic Canadians. The Coastal Communities Network (CCN) of Nova Scotia provides a forum to encourage dialogue and share information that promotes the survival and enhancement of our rural coastal communities. The goal of the Rural Communities Impacting Policy (RCIP) Project is to increase the ability of rural communities and organizations in Nova Scotia to access and use social science research in order to influence and develop policy that contributes to the health and sustainability of communities. The RCIP project is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. This report has been prepared for: Atlantic Health Promotion Research Centre Dalhousie University Suite 209 City Centre Atlantic 1535 Dresden Row Halifax, Nova Scotia, B3J 3T1 Phone: 902 494 2240 Fax: 902 494 3594 email: [email protected] -

CALA Magazine

Fall Issue 2007 www.nald.ca/cala What The Joy of would you like to learn this fall? LearningTruro ::: Colchester County Teaching Immigrants English (T.I.E.) Inspirational Student Stories Graduating Green Thumbs Learning Communities Symposium Bringing Learning To Life Innovative Communities Table Of Contents ______________________________ 4 - Teaching Immigrants English (T.I.E.) 6 - 35 Years Old, No Education, No Job... Now What? CALA Board Members 7 - Inspirational Student Story - Heather Wilmot 8 - Great Village Community Learning Network Executive: 9 - Inspirational Student Story - Shannon Wolfe Chair- Ken Henderson Past Chair-Shari Mallory-Shaw 11 - Inspirational Student Story - Chalayne Dumont Treasurer-Kathy MacCallum 14 - Graduating Green Thumbs Lech Krzywonos Nora MacDonald-Plourde 16 - Maggie’s Place - Early Language & Learning Jayne Hunter Bruce Berry 17 - Stewiacke Valley Learning Community Kathy Rector Debbie Farrell Tatamagouche Learning Community Network Lynda Marsh Alan Johnson 18 - Learning Communities Symposium Resource: 20 - Tutor’s Prespective Anna Parks Donna MacGillivray Margaret Hunt Wendy Robichaud 22 - Creating Learning Communities in Colchester 23 - Directory Program Coordinator: Debbie Farrell Instructors: Literacy, an important set of skills in Bonnie MacDonald today’s labor market,is much more that Colleen Hatfield reading,writing, and numeracy. ������������������������������������� It is the ability to understand and use printed The Joy of Learning Publication information in all kinds of daily activities. Literacy -

District N 2 Zones Zone 1 Clubs Baddeck Cabot Trail

District N 2 Zones Zone 1 Clubs Zone 1 Chair Baddeck Bob Jardine [email protected] 902-794-3892 Cabot Trail Glace Bay New Waterford Sydney Whycocomagh Zone 2 Clubs Zone 2 Chair Antigonish Earl Einarson [email protected] 902-863-1969 Canso Louisdale St. Mary's St. Peter’s Zone 3A Clubs Zone 3A Chair Amherst Tim Ripley [email protected] Oxford Parrsboro Springhill 2011 Zone 3B Clubs Zone 3B Chair Pictou Catherine Gibson [email protected] 902-698-3111 River John Stellarton Tatamagouche Zone 4 Clubs Zone 4 Chair Chezzetcook Joyce Gero [email protected] 902-895-0355 Enfield/Elmsdale Milford Musquodoboit Harbour Musquodoboit Valley Sheet Harbour Shubenacadie Truro Zone 5 Clubs Zone 5 Chair Canning Kim Stewart [email protected] 902-542-9828 Hantsport New Minas Port Williams Windsor Wolfville Zone 6 Clubs Zone 6 Chair Aylesford Mark Durnford [email protected] 902-538-1014 Berwick Coldbrook Kentville Kingston Zone 7 Clubs Zone 7 Chair Annapolis Royal Linda Baltzer [email protected] 902-825-6381 Bridgetown Deep Brook-Waldec Digby & Area Lawrencetown Middleton Zone 8 Clubs Zone 8 Chair Barrington Charlie Blake [email protected] 902-742-9762 Meteghan Pubnico Weymouth Branch Yarmouth Zone 9 Clubs Zone 9 Chair Bridgewater Bill Bruhm [email protected] 902-543-7415 Chester Basin-New Ross-Chester Liverpool Lockeport Mahone Bay New Germany Riverport Shelburne Zone 10 Clubs Zone 10 Chair Armdale-Fairview-Rockingham Veronica Webb [email protected] 902-864-3583 Beaver Bank-Kinsac Bedford Dalhousie University Fall River-Riverlake Hubbards Sackville Spryfield St. Margaret’s Bay Zone 11 Clubs Zone 11 Chair Cole Harbour Kevin MacNeil [email protected] 902-435-6650 Dartmouth Eastern Passage/Cow Bay Lake Echo Preston & Area . -

Long Range Outlook 2018-2019

2018-2019 Chignecto Central Long Range Outlook Regional Centre for Education Published: December 2019 Table of Contents Overview General Description ............................................................................................................................... 4 Senior Management Team .................................................................................................................... 4 Family of Schools Administrative Units .................................................................................................. 4 Geography ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Demographics ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Educational Goals, Priorities and Programming Vision-Mission-Values ........................................................................................................................... 7 2019-2020 Business Plan Priorities ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Goals ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 Programs and Student Services Public School Program ....................................................................................................................... -

Canada Lands - Atlantic First Nations Lands and National Parks

73° 72° 71° 70° 69° 68° 67° 66° 65° 64° 63° 62° 61° 60° 59° 58° 57° 56° 55° 54° 53° 52° 51° 50° 49° 48° 47° 46° 60° 61° Natural Resources Canada 46° CANADA LANDS - ATLANTIC FIRST NATIONS LANDS AND NATIONAL PARKS Killiniq Island Produced by the Surveyor General Branch, Geomatics Canada, Natural Resources Canada. Fo rb December 2011 Edition. es Sou dley nd Cape Chi Cap William-Smith To order this product contact: 60° Grenfell Sound Surveyor General Branch, Geomatics Canada, Natural Resources Canada 59° et Tunnissugjuak Inl Atlantic Client Liaison Unit, Amherst, Nova Scotia, Telephone (902) 661-6762 or Home Island E-mail: [email protected] rd Avayalik Islands Fio For other related products from the Surveyor General Branch, see website sgb.nrcan.gc.ca yuk lia ud Black Rock Point 73° Ikk d ior Saglarsuk Bay © 2011. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. k F eoo odl Eclipse Harbour No Cape Territok North Aulatsivik Island hannel Eclipse C Scale: 1:2 000 000 or one centimetre equals 20 kilometres Ryans Bay 20 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 kilometres Allu vi aq F Ungava Bay io rd ord lands Bay Lambert Conformal Conical Projection, Standard Parallels 49° N and 77° N iorvik\Fi Seven Is angalaks K 47° 59° Komaktorvik Fiord Cape White Handkerchief Trout Trap Fiord 58° TORNGAT MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK OF CANADA NOTE: Nachv iord a k F Gulch Cape This map is not to be used for defining boundaries. It is an index to First Nation Lands (Indian Reserves Rowsell Harbour as defined by the Indian Act) and National Parks.