Pursuing Her Initial Vice-Principalship: a Narrative Inquiry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dance Design & Production Drama Filmmaking Music

Dance Design & Production Drama Filmmaking Music Powering Creativity Filmmaking CONCENTRATIONS Bachelor of Master of Fine Arts Fine Arts The School of Filmmaking is top ranked in the nation. Animation Cinematography Creative Producing Directing Film Music Composition Picture Editing & Sound Design No.6 of Top 50 Film Schools by TheWrap Producing BECOME A SKILLED STORYTELLER Production Design & Visual Effects Undergraduates take courses in every aspect of the moving image arts, from movies, series and documentaries to augmented and virtual reality. Screenwriting You’ll immediately work on sets and experience firsthand the full arc of film production, including marketing and distribution. You’ll understand the many different creative leadership roles that contribute to the process and discover your strengths and interests. After learning the fundamentals, you’ll work with faculty and focus on a concentration — animation, cinematography, directing, picture editing No.10 of Top 25 American and sound design, producing, production design and visual effects, or Film Schools by The screenwriting. Then you’ll pursue an advanced curriculum focused on your Hollywood Reporter craft’s intricacies as you hone your leadership skills and collaborate with artists in the other concentrations to earn your degree. No.16 of Top 25 Schools for Composing for Film and TV by The Hollywood Reporter Filmmaking Ranked among the best film schools in the country, the School of Filmmaking produces GRADUATE PROGRAM experienced storytellers skilled in all aspects of the cinematic arts and new media. Students Top 50 Best Film Schools direct and shoot numerous projects alongside hands-on courses in every aspect of modern film Graduate students earn their M.F.A. -

Understanding and Negotiating the Secondary Vice-Principal Role: Perspectives of Secondary Principals

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-24-2016 12:00 AM Understanding and Negotiating the Secondary Vice-Principal Role: Perspectives of Secondary Principals Louis Lim The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Katina Pollock The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Education A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Education © Louis Lim 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Educational Leadership Commons Recommended Citation Lim, Louis, "Understanding and Negotiating the Secondary Vice-Principal Role: Perspectives of Secondary Principals" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 4039. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/4039 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This dissertation explores how secondary principals understand and negotiate the secondary vice-principal role. The principal assigns vice-principal duties so there is no standard description for the vice-principal role (Ontario Ministry of Education, 1990). My conceptual framework, based on the notions of role and work, informed the study. Using an interpretive basic, generic qualitative study approach, I conducted single 60 to 90 minute semi-structured interviews with 13 secondary principals from four Ontario district school boards. Data analysis was on-going and used a modified version of the constant comparative method for themes to emerge. Findings indicated that secondary principals expect their vice-principals to perform both operational and instructional tasks, although the school day remains dominated by operational duties related to supporting students and staff. -

Oecd Project

Improving School Leadership Activity Education and Training Policy Division http://www.oecd.org/edu/schoolleadership DIRECTORATE FOR EDUCATION IMPROVING SCHOOL LEADERSHIP COUNTRY BACKGROUND REPORT FOR NORTHERN IRELAND May 2007 This report was prepared for the OECD Activity Improving School Leadership following common guidelines the OECD provided to all countries participating in the activity. Country background reports can be found at www.oecd.org/edu/schoolleadership. Northern Ireland has granted the OECD permission to include this document on the OECD Internet Home Page. The opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the national authority, the OECD or its Member countries. The copyright conditions governing access to information on the OECD Home Page are provided at www.oecd.org/rights 1 OECD Report – Improving School Leadership Northern Ireland R J FitzPatrick - 2007 IMPROVING SCHOOL LEADERSHIP – COUNTRY BACKGROUND REPORT (NORTHERN IRELAND) CONTENTS Page 1. NATIONAL CONTEXT (Northern Ireland) 4 1.1 Introduction 4 1.2 The Current Economic and Social Climate 4 1.3 The Northern Ireland Economy 4 1.4 Society and Community 5 1.5 Education as a Government Priority for Northern Ireland 6 1.6 Priorities within Education and Training 7 1.7 Major Education Reforms 8 1.8 Priority Funding Packages 9 1.9 Early Years 10 1.10 ICT 10 1.11 Special Educational Needs and Inclusion 10 1.12 Education and Skills Authority 10 1.13 Targets and outcomes for the Education System 11 1.14 Efficiency 11 2. THE SCHOOL SYSTEM AND THE TEACHING WORKFORCE 13 -

Printable Stuntman Resume

JOHN COPEMAN STUNTMAN MEMBER SAG-AFTRA/ DGA MEMBER OF THE ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS AND SCIENCES NOMINEE- 2005 TAURUS WORLD STUNT AWARDS- BEST HIGH WORK “ THE FORGOTTEN” MOBILE: 910-616-9466 WWW.C-4STUNTSINC.COM FEATURES/ TV/ COMMERICIAL SLEEPY HOLLOW- 3 SEASONS TURN- SEASON 2 VAMPIRE DIARIES VICE PRINCIPALS DEATH OF EVA SOFIA VALDEZ EASTBOUND AND DOWN THE FORGOTTEN ALONG CAME A SPIDER UNDER THE DOME SOLVING CHARLIE ONE TREE HILL SURFACE TWENTY QUESTIONS DAWSON’S CREEK GATORADE SHE’S OUT OF MY LEAGUE NIGHTS IN RODANTHE CABIN FEVER 1 & 2 COLD STORAGE AMERICA’S MOST WANTED NATIONAL LAMPOONS PUCKED BROOKLYN RULES THE CHOICE PIRANHA 3DD SECRETS AND LIES BODY OF LIES KATE & LEOPOLD THE LOVELY BONES DAMAGES THE THOMAS CROWN AFFAIR THE CRAZIES THE MAIDEN HEIST THE HOAX THE BOUNTY HUNTER BEETHOVEN 4 NAILED RIGHT IN ALTERED ZOMBIELAND CHERRY FALLS SONG CATCHER BODY SNATCHERS 2 DIARY OF A HITMAN CARRIE 2 YOU’VE GOT MAIL HUDSON HAWK BLACK DOG VIRUS LOLITA BEAUTIFUL GIRLS PAVILLION KIMBERLY 12 MONKEYS DEAD PRESIDENTS MAXIMUM RISK NEW BEST FRIEND OFFICE KILLER A FURTHER GESTURE THE CROW EMPIRE RECORDS BULLET ( 1995) RADIOLAND MURDERS THE ROAD TO WELLVILLE CHASERS SUPER AMRIO BROS. THE HUDSUCKER PROXY LAST OF THE MOHICANS AMOS & ANDREW TRICK OR TREAT TUNE IN TOMORROW HACK BURNING VENGEANCE SHORT RIDE TURN OF FAITH THE SOPRANOS TARGET EARTH HOLY JOE GOING TO CALIFORNIA TECUMSEH BLACK MAGIC JOHN ADAMS THE DAY LINCOLN WAS SHOT THE INVISIBLE MAN THE TWILIGHT MAN BIONIC BREAKDOWN AMERICAN GOTHIC SHATTERED DREAMS *NY UNDERCOVER IN A CHILDS NAME BASTARD -

GORDON ANTELL Editor

GORDON ANTELL Editor Feature Films & Television PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO/PRODUCTION CO. INHERIT THE VIPER Anthony Jerjen Barry Films co-editor Prod: Michel Merkt, Benito Mueller, Cast: Josh Hartnett, Margarita Levieva, Bruce Dern Wolfgang Mueller VERSUS (digital series) Amy Rice go90 / Awesomeness Films Sam Boyd EP: Kelsey Jackson CODE BLACK (season 3) Nicole Rubio CBS / ABC Studios EP: Michael Seitzman PISS OFF, I LOVE YOU (digital series) Jessie McCormack Prod: Jason Kaminsky, Blair Skinner CAPTAIN HAGEN’S BED & BREAKFAST Rafael Friedan Riffraff Pictures Cast: Jessamine Kelley, Dino Petrera, Tyler Bellmon Prod: Joe Checchini BADSVILLE April Mullen Epic Pictures / Phillm Productions Cast: Robert Knepper, Tamara Duarte, Emilio Rivera Prod: David J. Phillips, Douglas Spain Winner: Best Editing – Maverick Film Awards DEFIANCE (seasons 2-3) Alan Arkush Syfy / Five & Dime Productions co-editor: season 3 Todd Slavkin EP: Todd Slavkin, Darren Swimmer, editor: season 2 webisodes Kevin Murphy THE BRINK (season 1) Tim Robbins HBO / Jerry Weintraub Productions additional editor Michael Lehman EP: Jay Roach, Roberto Benabib, Jerry Weintraub MOMENTS OF CLARITY Stev Elam Longstem Pictures / Phillm Productions Cast: Lyndsy Fonseca, Eric Roberts, Marguerite Moreau Co-Prod: David J. Phillips, Kristin Wallace Nominee: Best Editing – Maverick Film Awards THE ROAD WITHIN Gren Wells Troika Pictures / Amasia Entertainment co-editor P: Brent Emery, Bradley Gallo, Cast: Zoe Kravitz, Dev Patel, Kyra Sedgwick Michael A. Helfant NECESSARY ROUGHNESS (season 3, webisodes) -

HBO Signature Philippines Schedule December 2017

HBO Signature Philippines Schedule December 2017 Fri, Dec 1 Sat, Dec 2 1:15AM Reversion 12:45AM Cloverfield 2:40AM Ana Maria In Novela Land 2:10AM 10 Cloverfield Lane 4:15AM Cop Out 3:50AM The Fog 6:00AM Couples Retreat 5:20AM David McCullough Painting 8:15AM Nothing Left Unsaid: Gloria With Words Vanderbilt & Anderson 6:00AM Kareem: Minority Of One Cooper 7:25AM Philadelphia 10:00AM True Blood S3 09: 9:25AM Redemption Everything Is Broken 10:00AM Vice Principals S2 01: Tiger 10:55AM Crashing S1 03: Yard Sale Town 11:25AM Crashing S1 04: Barking 10:30AM Vice Principals S2 02: 11:55AM In The Gloaming Slaughter 1:00PM Philadelphia 11:00AM Vice Principals S2 03: The 3:05PM We Are Marshall King 5:15PM As You Like It 11:35AM Vice Principals S2 04: Think Change 7:20PM Game Change 12:05PM Vice Principals S2 05: A 9:15PM Curb Your Enthusiasm S9 Compassionate Man 09: The Shucker 12:40PM Vice Principals S2 06: The 10:00PM Barracuda S1 01 Most Popular Boy 10:55PM Ballers S3 04: Ride And Die 1:15PM Vice Principals S2 07: 11:25PM Insecure S2 04: Hella La Spring Break 11:55PM True Blood S3 10: I Smell A 1:45PM Vice Principals S2 08: Rat Venetian Nights 2:20PM Vice Principals S2 09: The Union Of The Wizard & The Warrior 2:55PM David McCullough Painting With Words 3:35PM Life According To Sam 5:10PM Duplicity 7:10PM Cloverfield 8:35PM Kareem: Minority Of One 10:00PM Life According To Sam 11:35PM The Bronze Published Dec 5 2017. -

NYTVF Overall PR 092215 11

PRESS NOTE: Media interested in covering any 2015 New York Television Festival events can apply for credentials by completing this form at NYTVF.com. 11TH ANNUAL NEW YORK TELEVISION FESTIVAL TO FEATURE WGN AMERICA'S MANHATTAN AND A SPECIAL EVENT HOSTED BY NBC DIGITAL ENTERPRISES FEATURING DAN HARMON AS PART OF OPENING NIGHT DOUBLE-HEADER *** Official Artists to have exclusive access to an Industry Welcome Keynote from Joel Stillerman of AMC and SundanceTV and a series of events sponsored by Pivot, including a screening of Please Like Me and Q&A with Josh Thomas, and the NYTVF 2015 Opening Night Party, hosted with Time Warner Cable Free Festival line-up to include Creative Keynote Showrunner Panel; BAFTA, CNN, Pop (Schitt’s Creek) and truTV (Those Who Can’t)-hosted special events; screenings of 50 Official Selections from the Independent Pilot Competition; closing night awards reception and more [NEW YORK, NY, September 22, 2015] – The NYTVF today announced schedule highlights for its eleventh annual New York Television Festival, which begins Monday, October 19 with an opening night screening celebrating season two of WGN America's Manhattan, the critically acclaimed, Emmy Award-winning drama produced by Lionsgate Television, Skydance Television and Tribune Studios. Following a first-look at the episode set to premiere the next night, cast members John Benjamin Hickey, Rachel Brosnahan, Ashley Zukerman, Michael Chernus, Katja Herbers and Mamie Gummer, along with series creator, writer and executive producer Sam Shaw and director and executive producer Thomas Schlamme, have been confirmed to participate in a talk-back panel. Also on opening night will be a special event hosted by NBCUniversal Digital Enterprises, featuring a live performance by Dan Harmon and special guests. -

TRAVIS SITTARD Editor

TRAVIS SITTARD Editor PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS MEET CUTE Alex Lehmann WEED ROAD PICTURES Feature Film Dan Reardon, Akiva Goldsman Greg Lessans, Rachel Reznick Santosh Govindaraju HE’S ALL THAT Mark Waters MIRAMAX FILMS Feature Film Bill Wohlken, Andrew Panay BLACK MONDAY Various Directors SONY / SHOWTIME Season 2 Jordan Cahan, David Caspe Giselle Chruszcz Johnson Aaron Kaplan PREACHER Various Directors POINT GREY PICTURES / AMC Seasons 2–3 Sabra Ruel, Sam Catlin POWERLESS Various Directors WARNER BROS. TV / DC COMICS Season 1 NBC Michael Patrick Jann, Ben Queen THE DISASTER ARTIST James Franco GOOD UNIVERSE Feature Film Hans Ritter, Kelli Konop Additional Editor BAD SANTA 2 Mark Waters MIRAMAX Feature Film Leslie Belzberg VICE PRINCIPALS Various Directors FOX 21 / HBO Series Stephanie Laing, Danny McBride Official Selection – SXSW Film Festival Jody Hill SALEM ROGERS: Mark Waters AMAZON STUDIO MODEL OF THE YEAR 1998 Pixie Wespiser, Will Graham Pilot Lindsey Stoddart RECTIFY Various Directors GRAN VIA PRODUCTIONS Seasons 1 - 2 SUNDANCE CHANNEL Mark Johnson EASTBOUND & DOWN Various Directors HBO Seasons 1 – 4 Editor, Supervising Editor A BAG OF HAMMERS Brian Crano SUBMARINE ENTERTAINMENT Feature Film MPI MEDIA GROUP THAT EVENING SUN Scott Teems DOGWOOD ENTERTAINMENT Feature Film WHILE SHE WAS OUT Susan Montford INSIGHT FILM STUDIOS Feature Film VOLTAGE PICTURES Additional Editor ANCHOR BAY FILMS ASSASSINATION OF A Brett Simon VERTIGO ENTERTAINMENT HIGH SCHOOL PRESIDENT YARI FILM GROUP Feature Film Assistant Editor SNOW ANGELS David Gordon Green CROSSROADS FILMS Feature Film WARNER INDEPENDENT Additional Editor INNOVATIVE-PRODUCTION.COM | 310.656.5151 . -

Visiting Committee Chairs

2727 N. Cedar Ave Fresno, CA 93703 Tel: (559) 248-5100 www.fresnou.org/schools/mclane WASC/CDE Focus on Learning Accreditation Manual 2014-2015 Edition McLane High School WASC/CDE Self-Study Report Fresno Unified School District 2309 Tulare St. Fresno, CA 93721 (559) 457-3000 www.fresnounified.org District Administration Michael Hanson: Superintendent of Schools Board of Education Lindsay Cal Johnson-President Christopher De La Cerda-Clerk Valerie Davis-Member Luis A. Chavez-Member Carol Mills, J.D.-Member Janet Ryan-Member Brooke Asjian-Member 1 McLane High School WASC/CDE Self-Study Report McLane High School 2727 N. Cedar Ave Fresno, CA 93703 (559) 248-5100 www.fresnou.org/schools/mclane Administrative Team Scott Lamm: Principal Rick Santos: Vice Principal Connie Cha: Vice Principal John Kaup: Vice Principal Wendy McCormick: Vice Principal Dora Leal: Head Counselor WASC Self Study Leadership Team Wendy McCormick: Chair Monorith Arun: Co-Chair Shannon West: Co-Chair Dionne Howell: Organization and Leadership Shannon West: Curriculum Janine Anderson: Instruction Keith Raines: Instruction Monorith Arun: Assessment Lori Mehl: Assessment Kyle Thornton: School Culture and Support 2 McLane High School WASC/CDE Self-Study Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface...........................................................................................................................................4 Chapter I: Student/Community Profile and Supporting Data and Findings ................................6 Chapter II: Progress Report ......................................................................................................52 -

Busy Philipps Is a New York Times Best-Selling Author, Actress, Writer and Recently Late-Night Talk Show Host of BUSY TONIGHT

Busy Philipps is a New York Times Best-Selling author, actress, writer and recently late-night talk show host of BUSY TONIGHT. Philipps served as executive producer on the show, alongside Tina Fey. In 2018, Philipps released a collection of humorous autobiographical essays in her book THIS WILL ONLY HURT A LITTLE that was immediately a New York Times Best Seller the first week. The book offers the same unfiltered and candid storytelling that can be found on her social media pages and will be published by Simon and Schuster’s Touchstone division. On the big screen, Philipps was recently seen in the STX romantic comedy, I FEEL PRETTY, opposite Amy Schumer and Michelle Williams, and directed by Abby Kohn and Marc Silverstein. She also appeared in Joel Edgerton’s thriller THE GIFT, alongside Jason Bateman and Rebecca Hall. Released by STX, the film tells the story of a young married couple whose lives are thrown into a tailspin when an acquaintance from the husband’s path brings mysterious gifts and a horrifying secret to light. Previously, Philipps was seen in HBO’s VICE PRINCIPALS, an 18-episode comedy series from Eastbound & Down creators Danny McBride and Jody Hill. The series ran for 2 seasons and starred Danny McBride, Walton Goggins, Kimberly Herbert Gregory and Georgia King. Philipps played Gale Liptrapp, the ex-wife of McBride’s character and loving mother to his child. Also on television, she starred opposite Courteney Cox on the popular TBS comedy COUGAR TOWN where she played ‘Laurie Keller.’ Philipps currently resides in Los Angeles with her husband and two daughters. -

Television Academy Awards

2018 Primetime Emmy® Awards Nominees Per Program The Accidental Wolf OUTSTANDING ACTRESS IN A SHORT FORM COMEDY OR DRAMA SERIES Adventure Time OUTSTANDING SHORT FORM ANIMATED PROGRAM aka Wyatt Cenac OUTSTANDING SHORT FORM COMEDY OR DRAMA SERIES Alexa & Katie OUTSTANDING CHILDREN'S PROGRAM Alexa Loses Her Voice OUTSTANDING COMMERCIAL Alias Grace OUTSTANDING MUSIC COMPOSITION FOR A LIMITED SERIES, MOVIE OR SPECIAL (ORIGINAL DRAMATIC SCORE) The Alienist OUTSTANDING PRODUCTION DESIGN FOR A NARRATIVE PERIOD OR FANTASY PROGRAM (ONE HOUR OR MORE) OUTSTANDING CINEMATOGRAPHY FOR A LIMITED SERIES OR MOVIE OUTSTANDING PERIOD COSTUMES OUTSTANDING MAIN TITLE DESIGN OUTSTANDING LIMITED SERIES OUTSTANDING SPECIAL VISUAL EFFECTS IN A SUPPORTING ROLE Altered Carbon OUTSTANDING MAIN TITLE DESIGN OUTSTANDING SPECIAL VISUAL EFFECTS The Amazing Race OUTSTANDING CINEMATOGRAPHY FOR A REALITY PROGRAM OUTSTANDING DIRECTING FOR A REALITY PROGRAM OUTSTANDING PICTURE EDITING FOR A STRUCTURED OR COMPETITION REALITY PROGRAM OUTSTANDING REALITY-COMPETITION PROGRAM America's Got Talent OUTSTANDING LIGHTING DESIGN/LIGHTING DIRECTION FOR A VARIETY SERIES American Dad! OUTSTANDING CHARACTER VOICE-OVER PERFORMANCE American Horror Story: Cult OUTSTANDING PRODUCTION DESIGN FOR A NARRATIVE CONTEMPORARY PROGRAM (ONE HOUR OR MORE) OUTSTANDING HAIRSTYLING FOR A LIMITED SERIES OR MOVIE OUTSTANDING MAKEUP FOR A LIMITED SERIES OR MOVIE (NON-PROSTHETIC) OUTSTANDING PROSTHETIC MAKEUP FOR A SERIES, LIMITED SERIES, MOVIE OR SPECIAL OUTSTANDING LEAD ACTRESS IN A LIMITED SERIES OR MOVIE -

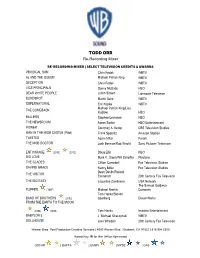

TODD ORR Re-Recording Mixer

TODD ORR Re-Recording Mixer RE-RECORDING MIXER | SELECT TELEVISION CREDITS & AWARDS PRODIGAL SON Chris Fedak WBTV AJ AND THE QUEEN Michael Patrick King WBTV DECEPTION Chris Fedak WBTV VICE PRINCIPALS Danny McBride HBO DEAR WHITE PEOPLE Justin Simien Lionsgate Television BLINDSPOT Martin Gero WBTV SUPERNATURAL Eric Kripke WBTV Michael Patrick King/Lisa THE COMEBACK Kudrow HBO BALLERS Stephen Levinson HBO THE NEWSROOM Aaron Sorkin HBO Entertainment POWER Courtney A. Kemp CBS Television Studios MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE (Pilot) Frank Spotnitz Amazon Studios TWISTED Adam Milch Pariah THE MOB DOCTOR Josh Berman/Rob Wright Sony Pictures Television ENTOURAGE (2010) (2012) Doug Ellin HBO BIG LOVE Mark V. Olsen/Will Scheffer Playtone THE GLADES Clifton Campbell Fox Television Studios SAVING GRACE Nancy Miller Fox Television Studios Dean Devlin/Roland THE VISITOR Emmerich 20th Century Fox Television THE BIG EASY Jaqueline Zambrano USA Network The Samuel Goldwyn FLIPPER (1997) Michael Nankin Company Tom Hanks/Steven BAND OF BROTHERS (2002) Spielberg DreamWorks FROM THE EARTH TO THE MOON (1998) (1999) Tom Hanks Imagine Entertainment BABYLON 5 J. Michael Straczynski WBTV DOLLHOUSE Joss Whedon 20th Century Fox Television Warner Bros. Post Production Creative Services | 4000 Warner Blvd. | Burbank, CA 91522 | 818.954.5305 Award Key: W for Win | N for Nominated OSCAR | BAFTA | EMMY | MPSE | CAS BATTLESTAR GALACTICA Glen A. Larson British Sky Broadcasting James Cameron/Charles H. DARK ANGEL Eglee 20th Century Fox Television JANE BY DESIGN April Blair ABC Family DROP DEAD DIVA Josh Berman Sony Pictures Television MAD MEN (2010) (2010) Matthew Weiner Lionsgate Television THE SOPRANOS (1999/2000/2003/2004/2007) (2000) (2001/2005/2007/2008) David Chase HBO THE BLACK DONNELLYS Paul Haggis NBC REVELATIONS David Seltzer NBC Enterprises BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER (1999) Joss Whedon 20th Century Fox Television David Greenwalt/Joss ANGEL Whedon 20th Century Fox Television SPACE: ABOVE AND BEYOND Glen Morgan Village Roadshow Pictures Warner Bros.