Rural Settlement in Cheshire Some Problems of Origin and Classification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application No: 12/1349N Location: HUNSTERSON FISHERIES, LAND OFF BIRCHALL MOSS LANE, HUNSTERSON, NANTWICH, CHESHIRE, CW5 7PH Pr

Application No: 12/1349N Location: HUNSTERSON FISHERIES, LAND OFF BIRCHALL MOSS LANE, HUNSTERSON, NANTWICH, CHESHIRE, CW5 7PH Proposal: Proposed Fishermans Retreat Building Applicant: MR F STRICKLAND Expiry Date: 27-Jun-2012 SUMMARY RECOMMENDATION: APPROVE subject to conditions Main issues: • The principle of the development • The impact of the design • The impact upon neighbouring amenity • The impact upon protected species REASON FOR REFERRAL Councillor J. Clowes has called in this application to Southern Planning Committee for the following reasons: • ‘Inappropriate and unsustainable intensification of activity on agricultural land in the open countryside. • Inappropriate size, structure and materials of the proposed building. • Consequent visual intrusion on a green field site in the open countryside. • Hazardous entry and exit to and from the site on Bridgemere Lane. • Inadequate preparation in terms of siting and management of proposed septic tank foul drainage system. • Current informal ‘presumptive’ car parking arrangements are inadequate for the numbers of vehicles proposed in this application.’ DESCRIPTION OF SITE AND CONTEXT The application site relates to land to the south of Bridgemere Lane, Hunsterson, Nantwich within the Open Countryside. The land relates to a section of open paddock adjacent to a large fishing pond set approximately 150 metres to the south of the road. Currently on site is an unauthorised touring caravan which appears to be being used as a makeshift ‘fisherman’s hut’. DETAILS OF PROPOSAL Revised plans have been submitted for the erection of a purpose built fisherman’s hut. The proposed unit would measure approximately 6.6 metres in length, 5 metres in width and would have a pitched roof approximately 4.1 metres in height from ground floor level. -

A500 Dualling) (Classified Road) (Side Roads) Order 2020

THE CHESHIRE EAST BOROUGH COUNCIL (A500 DUALLING) (CLASSIFIED ROAD) (SIDE ROADS) ORDER 2020 AND THE CHESHIRE EAST BOROUGH COUNCIL (A500 DUALLING) COMPULSORY PURCHASE ORDER 2020 COMBINED STATEMENT OF REASONS [Page left blank intentionally] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Purpose of Statement ........................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Statutory powers ............................................................................................................... 2 2 BACKGROUND AND SCHEME DEVELOPMENT ........................................................................... 3 2.1 Regional Growth ................................................................................................................ 3 2.2 Local Context ..................................................................................................................... 4 2.3 Scheme History .................................................................................................................. 5 3 EXISTING AND FUTURE CONDITIONS ........................................................................................ 6 3.1 Local Network Description ................................................................................................ 6 3.2 Travel Patterns ............................................................................................................... -

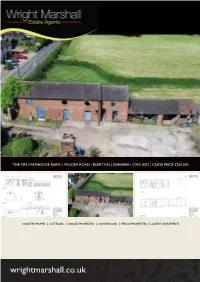

Wrightmarshall.Co.Uk

‘THE FIRS FARMHOUSE BARN’ | WOORE ROAD | BUERTON | CHESHIRE | CW3 0DD | GUIDE PRICE £250,000 COUNTRY HOMES │ COTTAGES │ UNIQUE PROPERTIES │ CONVERSIONS │ PERIOD PROPERTIES │ LUXURY APARTMENTS wrightmarshall.co.uk ‘The Firs Farmhouse Barn’, Woore Road, Buerton, Cheshire, CW3 0DD A superb opportunity to acquire a period detached barn requiring conversion standing in a wonderful rural location with views over adjoining farmland. With the benefit of planning permission for the conversion to one dwelling (Ref: 17/3939N). The existing barn is positioned end on to the road itself, and boasts wonderful views to the side & rear. Access presently is shared with the adjoining property, 'The Firs Farmhouse', however provision has been made within the planning permission, for a separate entrance to be created in due course for the sole use of the farmhouse, therefore the barn will have its own access leading to the parking, proposed garage etc. NO CHAIN NEARBY AUDLEM VILLAGE DIRECTIONS In a county considered as prosperous as Cheshire, a village as well Take the A529 Audlem Road out of Nantwich and continue for serviced as Audlem may become complacent about the services & approximately 7 miles into Audlem village. Upon reaching the village facilities it provides but it has demonstrated that it certainly doesn't square turn left onto the A525 Woore Road, continue for take its facilities for granted. Annual events in the Village include a approximately 1.3 miles and the barn will be observed on the left hand Transport Festival, Music & Arts Festival and Open Gardens Weekend. side. Recent Awards won by Audlem Village: Regional title for North (AUDLEM 1.5 miles : NANTWICH 7 miles : NEWCASTLE UNDER England as well as overall award for Building Community Life LYME 12 miles : CREWE MAINLINE RAILWAY STATION 10 miles : (sponsored by DEFRA-Department for Environment, Food & Rural M6 JUNCTION 16, 12 miles) Affairs) in the 2005 Calor Village of the Year. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England Report No.391 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION for ENGLAND

Local Government Boundary Commission For England Report No.391 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Sir Nicholas Morrison KCB DEPUTY CHAIRMAN Mr J M Rankin MEMBERS Lady Bowden Mr J T Brockbank Mr R R Thornton CBE. DL Mr D P Harrison Professor G E Cherry To the Rt Hon William Whitelaw, CH MC MP Secretary of State for the Home Department PROPOSALS FOR THE FUTURE ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE COUNTY OF CHESHIRE 1. The last Order under Section 51 of the Local Government Act 1972 in relation to the electoral arrangements for the districts in the County of Cheshire was made on 28 September 1978. As required by Section 63 and Schedule 9 of the Act we have now reviewed the electoral arrangements for that county, using the procedures we had set out in our Report No 6. 2. We informed the Cheshire County Council in a consultation letter dated 12 January 1979 that we proposed to conduct the review, and sent copies of the letter to the district councils, parish councils and parish meetings in the county, to the Members of Parliament representing the constituencies concerned, to the headquarters of the main political parties and to the editors both of » local newspapers circulating in the county and of the local government press. Notices in the local press announced the start of the review and invited comments from members of the public and from interested bodies. 3» On 1 August 1979 the County Council submitted to us a draft scheme in which they suggested 71 electoral divisions for the County, each returning one member in accordance with Section 6(2)(a) of the Act. -

Wrightmarshall.Co.Uk Fineandcountry.Com

QUOISLEY BRIDGE HOUSE | QUOISLEY BRIDGE | WHITCHURCH | SY13 4HG GUIDE PRICE £500,000 COUNTRY HOMES │ COTTAGES │ UNIQUE PROPERTIES │ CONVERSIONS │ PERIOD PROPERTIES │ LUXURY APARTMENTS wrightmarshall.co.uk fineandcountry.com 'Quoisley Bridge House', Quoisley Bridge, Whitchurch, Cheshire, SY13 4HG Quoisley Bridge House is a magnificent Four Bedroom, Two Bathroom, Detached Character Country Residence, offering just over 3 acres of splendid gardens, orchard & grazing land with detached stables, garage & small barn, adjoining countryside. The spacious accommodation comprises: Entrance Hall, Snug, Conservatory, Formal Dining Room, Kitchen open to Dining/Family Room, Utility, WC, Drawing Room. First Floor Landing: Master Bedroom One, Dressing Area & Ensuite, Bedroom Two, Bedrooms Three & Four, Bath & Shower Room, Separate WC. Electric gates & approx 60 metre drive leads to the property. Magnificent parkland-style gardens with beautiful ornamental pond, orchard & grazing land, all enjoying complete privacy. Reception Hall / Snug DIRECTIONS Proceed from Nantwich along Welsh Row (A51) to AGENTS NOTE:- 'Quoisley Bridge House' is a most impressive Acton. Turn left at St Marys Church into Monks Lane & proceed detached country residence situated adjoining magnificent open through Burland village. At the main A49 junction, turn left onto the countryside. The current owners have beautifully enhanced the A49 itself passing the Cholmondeley Arms Public House. After approx property which combines charm & character with modern 3.5 miles, the property will be observed on the left hand side, marked conveniences, whilst having a most engaging garden setting. For by our 'For Sale' boards. prospective purchasers simply wishing to live the 'good life', of an equestrian or horticultural persuasion, this property is ideal for a wide QUOISELEY BRIDGE Quoisley Bridge is a rural, predominantly range of requirements. -

Early Methodism in and Around Chester, 1749-1812

EARIvY METHODISM IN AND AROUND CHESTER — Among the many ancient cities in England which interest the traveller, and delight the antiquary, few, if any, can surpass Chester. Its walls, its bridges, its ruined priory, its many churches, its old houses, its almost unique " rows," all arrest and repay attention. The cathedral, though not one of the largest or most magnificent, recalls many names which deserve to be remembered The name of Matthew Henry sheds lustre on the city in which he spent fifteen years of his fruitful ministry ; and a monument has been most properly erected to his honour in one of the public thoroughfares, Methodists, too, equally with Churchmen and Dissenters, have reason to regard Chester with interest, and associate with it some of the most blessed names in their briefer history. ... By John Wesley made the head of a Circuit which reached from Warrington to Shrewsbury, it has the unique distinction of being the only Circuit which John Fletcher was ever appointed to superintend, with his curate and two other preachers to assist him. Probably no other Circuit in the Connexion has produced four preachers who have filled the chair of the Conference. But from Chester came Richard Reece, and John Gaulter, and the late Rev. John Bowers ; and a still greater orator than either, if not the most effective of all who have been raised up among us, Samuel Bradburn. (George Osborn, D.D. ; Mag., April, 1870.J Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.archive.org/details/earlymethodisminOObretiala Rev. -

Cheshire East Care Services Directory 2015

Cheshire East Care Services Directory 2015 Tatton Hall The comprehensive guide to choosing and paying for your care • Home support • Housing options • Care helpline • Care homes Cheshire East Council In association with www.carechoices.co.uk Publications The Home Care Specialists Do you need a Helping Hand? “We are incredibly fortunate to have such dedicated Live-in Care... an alternative people, like the staff at Helping Hands, caring for the vulnerable and the to residential care. elderly members of the communities.” At Helping Hands we have been providing award winning Lisa Carr, Director of The quality home care since 1989. Still family run, we apply our Great British Care Awards local knowledge and 25 years of home care experience to offer ds 25th A an nn H iv one to one care that enables you or your loved one to remain g e n r i s p a l r e y at home with compassion and dignity. H Our locally based Carers are able to balance independent 25Years living with bespoke care needs by assisting with housekeeping, companionship, providing a break for an existing care giver, personal care, support with continence and hospital discharge. So if you are looking for an alternative to residential care or extra support for those everyday tasks that are becoming a little more difficult, then we’re here to help - 24 hours per day, 7 days per week. To find out how we can help you, call: 01270 861 745 or visit: www.helpinghands.co.uk Contents Introduction from Cheshire East Council 4 Paying for care 19 Healthy lifestyles 5 Protecting adults from harm -

The Warburtons of Sandbach and Nantwich

The Warburtons of Sandbach and Nantwich Ray Warburton Based on Input from Daphne Warburton and Heather Jones Last Updated: 20th January 2012 Table of Contents The. .Descendants . of. Joseph. .Warburton . .of . Sandbach. .1 . Descendants. of. Joseph. .Warburton . .5 . First. .Generation . .5 . Second. .Generation . .5 . Third. .Generation . .8 . Fourth. .Generation . .15 . Fifth. .Generation . .18 . Sixth. .Generation . .19 . Name. Index. .20 . Produced by Legacy on 21 Jan 2012 The Descendants of Joseph Warburton of Sandbach 1 1-Joseph Warburton +Mary Annie c. Abt 1801 2-Ralph Warburton b. Abt 1817, Elton, Sandbach, Cheshire, d. 6 Jan 1886, Newhall, Cheshire +Mary Foxley b. 3 Mar 1809, Brindley, Cheshire, d. After 1891 3-Jane Warburton b. Abt 12 Mar 1837, Warmingham, Cheshire 3-Joseph Warburton b. 15 Dec 1839, Warmingham, Cheshire, d. 1846 3-Thomas Warburton b. 1841, Warmingham, Cheshire, d. 1895, Bradwall, Cheshire +Hannah Williams b. Abt 1846, Burleydam, Cheshire, d. After 1901 4-John Warburton b. 1863, Aston By Newhall, Cheshire, d. 1890 4-Martha Warburton b. 1866, Nantwich, Cheshire, d. After 1901 4-Ada Warburton b. 1870, Sandbach, Cheshire, d. 1895, Bradwall, Cheshire +Frederick Fortune b. Abt 1852, Bristol, Gloucestershire 4-Mary Alice Warburton b. 1872, Elton, Sandbach, Cheshire +John Barratt 4-Rose Ann Warburton b. 1876, Bradwall, Cheshire, d. 1885, Bradwall, Cheshire 4-Elizabeth Warburton b. 1878, Bradwall, Cheshire 4-Emma Warburton b. 1880, Bradwall, Cheshire, d. 1885, Bradwall, Cheshire 4-Thomas Frederick Warburton b. 1883, Bradwall, Cheshire 3-John Warburton b. 1843, Warmingham, Cheshire, d. After 1901 +Sarah Walker b. Abt 1833, Elton, Sandbach, Cheshire, d. After 1901 4-Mary Elizabeth Warburton b. -

Local Accommodation Used and Suggested by Keele University Visitors

Local accommodation used and suggested by Keele University visitors Keele and Madeley and Betley THE OLD SCHOOL KEELE (Guest House or B&B) Church Bank, Keele ST5 5AT Tel 01782-619638 www.theoldschoolkeele.co.uk [email protected] MADELEY OLD HALL (Guest House or B&B) Poolside, Madeley, Crewe CW3 9DX Tel 01782 750209 SLATER’S COUNTRY INN: (Hotel) Stone Road, Baldwins Gate, Newcastle, Staffordshire ST5 5ED Tel 01782-680052 http://www.slaterscountryinn.co.uk ADDERLEY GREEN FARM (B&B) Heighley Castle Lane, Betley, Crewe, CW3 9BA Tel 01270 820203 http://www.smoothhound.co.uk/a12558.html BETLEY COURT FARM (B&B) Betley, near Crewe, CW3 9BH Tel 01270 820229 NEW HAYES FARM (B&B) Trentham Road, Butterton, Newcastle, Staffs. ST5 4DX Tel 01782 680889 CHURCH FARM (Guest House or B&B) Crown Bank, Talke, Stoke-on-Trent ST7 1PU Tel 01782-782518 www.churchfarmguesthouse.co.uk CHESTNUT GRANGE (Guest House or B&B) Windmill House, Rough Close, Stoke-on-Trent ST3 7PJ Tel 01782-396084 WHEATSHEAF INN AT ONNELEY (Guest House or B&B) Barhill Road, Onneley, Crewe CW3 9QF Tel 01782 751581 WYCHWOOD PARK (DE VERE VENUES) (Hotel) Wychwood Park, Weston, Crewe, Cheshire, CW2 5GP Tel 01270 829200 http://www.deverevenues.co.uk/locations/wychwood-park Newcastle Town Centre and surroundings BOROUGH ARMS HOTEL: (Hotel) King Street, Newcastle, Staffordshire ST5 1HX, Tel 01782-629421 http://www.borough-arms-hotel.co.uk CLAYHANGER: (Guest House or B&B) 40-42 King Street, Newcastle, Staffs ST5 1HX, Tel 01782-714428 http://www.a1tourism.com/uk/a12601.html [email protected],co.uk THE CORRIE (Guest House or B&B) 13 Newton Street, Basford, Stoke on Trent ST4 6JN Tel 01782-614838 www.thecorrie.co.uk [email protected] GRAYTHWAITE (Guest House or B&B) 106 Lancaster Road, Newcastle, Staffordshire, ST5 1DS. -

Chapter 2 the Historical Background

CHAPTER 2 THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1 5 I GEOGRAPHICAL AND CLIMATIC FOUNDATIONS As an area of historical study the Greater milder climate, by comparison both with the Manchester County has the disadvantage of being moors and with other westerly facing parts of without an history of its own. Created by Act Britain. Opening as they do on to what is, of Parliament a little over ten years ago, it climatically speaking, an inland sea, they joins together many areas with distinct avoid much of the torrential downpours brought histories arising from the underlying by Atlantic winds to the South West of England. geographical variations within its boundaries. At the same time the hills give protection from the snow bearing easterlies. The lowland areas The Greater Manchester County is the are fertile, and consist largely of glacial administrative counterpart of 20th century deposits. urban development which has masked the diversity of old pre-industrial southeast In the northwest of the Greater Manchester Lancashire and northeast Cheshire. County the plain rises around Wigan and Standish. For centuries the broad terraced The area has three dominant geographic valley of the Rivers Mersey and Irwell, which characteristics: the moorlands; the plains; and drains the plain, has been an important barrier the rivers, most notably the Mersey/Irwell to travel because of its mosses. Now the system. region's richest farmland, these areas of moss were largely waste until the early 19th century, when they were drained and reclaimed. The central area of Greater Manchester County, which includes the major part of the The barrier of the Mersey meant that for conurbation, is an eastward extension of the centuries northeast Cheshire developed .quite Lancashire Plain, known as the 'Manchester separately from southeast Lancashire, and it Embayment1 because it lies, like a bay, between was not until the twenties and thirties that high land to the north and east. -

Higher Den Farm Higher Den Farm Wrinehill

higher den farm higher den farm wrinehill At Gleave Homes, we know that selecting and purchasing your new home is one of the most important and exciting decisions you will ever make. We specialise in bringing bespoke residential developments in carefully chosen locations throughout Cheshire and the North West and, as a result, each and every home we build is designed to help make your decision easier. higher den farm den lane wrinehill cheshire cw3 9bx Higher Den Farm is an exclusive development of just five contemporary barn conversions retaining much of the original character. Attention to detail ensures that each home has been planned to maximise the use of space through imaginative design, providing homes of elegance and originality. Each home benefits from the highest standard of specification with contemporary Hacker kitchens, featuring an integrated Neff fridge, freezer, hob, oven, microwave and dish washer appliances, Roca bathroom suites with Hansgrohe taps and oak flooring to all main living areas. Naturally each property comes with the warranty of a 10 year Premier Guarantee, as approved by the Council of Mortgage Lenders. Higher Den Farm has a broad allure, with good access to the M6 (junction sixteen 6 miles) and main line rail links at Crewe Station (7 miles) appealing to commuters, convenient primary and high schools are within 4 miles for families and the rural location and excellent views offering that rare retreat from the hustle of city life. Wrinehill is situated on the edge of Betley (1.5 miles), a small market town listed in the Domesday Book of 1086 and Nantwich is within 8 miles. -

Residents Ideas for Wildboarclough and Macclesfield Forest

Residents Ideas for Wildboarclough and Macclesfield Forest Findings of the Residents’ Survey in January 2012 1 ‘People here are passionate about the countryside and their heritage. It binds people together. Each day, when I come home from work I look across the valley, and consider what a privilege it is to live in such a spectacularly beautiful area.’ 2 Acknowledgements Thanks go to Wincle School, Verena Breed , Maria Leitner and Liz Topalian for funding the printing of the survey forms and this report, Irene Belfield, Hilda Mitchell, and Erica Whitehead for their help and support, and Greg and Janet Robinson for printing notices when my machine wouldn’t! Special thanks go to our Postie Ray for his advice and support, without which this project could not have been achieved. I am grateful to all the residents who took the time to share their concerns and ideas by participating in the survey. Caroline Keightley January 2012 3 The findings of the Wildboarclough and Macclesfield Forest Residents Survey 2012 Introduction On 1 December the Parish Meeting agreed to a proposal to undertake a survey of all residents in order to find out people’s concerns, ideas, and priorities for action. The survey results can focus the discussion of future Parish Meetings. Why Have A Survey? The aim is to - Get the views of residents who cannot get to, or who don’t like attending the Parish meeting. It gives everybody a chance to air ideas for supporting and sustaining our village life. Make the Parish Meeting more responsive, effective, and think ahead- it allows us to ‘take stock’.