Stories in Stone Robben Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cape Town's Film Permit Guide

Location Filming In Cape Town a film permit guide THIS CITY WORKS FOR YOU MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR We are exceptionally proud of this, the 1st edition of The Film Permit Guide. This book provides information to filmmakers on film permitting and filming, and also acts as an information source for communities impacted by film activities in Cape Town and the Western Cape and will supply our local and international visitors and filmmakers with vital guidelines on the film industry. Cape Town’s film industry is a perfect reflection of the South African success story. We have matured into a world class, globally competitive film environment. With its rich diversity of landscapes and architecture, sublime weather conditions, world-class crews and production houses, not to mention a very hospitable exchange rate, we give you the best of, well, all worlds. ALDERMAN NOMAINDIA MFEKETO Executive Mayor City of Cape Town MESSAGE FROM ALDERMAN SITONGA The City of Cape Town recognises the valuable contribution of filming to the economic and cultural environment of Cape Town. I am therefore, upbeat about the introduction of this Film Permit Guide and the manner in which it is presented. This guide will be a vitally important communication tool to continue the positive relationship between the film industry, the community and the City of Cape Town. Through this guide, I am looking forward to seeing the strengthening of our thriving relationship with all roleplayers in the industry. ALDERMAN CLIFFORD SITONGA Mayoral Committee Member for Economic, Social Development and Tourism City of Cape Town CONTENTS C. Page 1. -

Basic Assessment Process for the Proposed Legal Framework Renewable Energy Generation Facility on Robben Island, Western Cape

4 Background Information Document BASIC ASSESSMENT PROCESS FOR THE PROPOSED LEGAL FRAMEWORK RENEWABLE ENERGY GENERATION FACILITY ON ROBBEN ISLAND, WESTERN CAPE. The National Environmental Management Act, Act 107 of 1998 (NEMA) is South Africa’s principal environmental regulatory instrument. NEMA and its Regulations promulgated under the amended NEMA in Government Notice Regulation (GNR.) 982, 983, 984 and 985 of 2014; BACKGROUND INFORMATION DOCUMENT specify activities subject to environmental authorisation prior to implementation. Activities listed PROPONENT: ROBBEN ISLAND MUSEUM C/O DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM under GNR. 983 (Listing Notice 1) and 985 (Listing Notice 3) require environmental authorisation through the undertaking of a Basic Assessment (BA) and those listed under GNR. 984 (Listing Notice 2) require a Scoping and Environmental Impact Assessment (S&EIA) to be undertaken. PURPOSE OF THIS DOCUMENT WSP|PB has been appointed by the This proposed development triggers activities listed under GN.R 983 and GN.R 985 and This background information document (BID) introduces National Department of Tourism as the therefore requires a Basic Assessment to be undertaken to obtain environmental authorisation all stakeholders to the proposed project. This document independent environmental assessment in terms of NEMA. The potential listed activities associated with the project are summarised forms part of the environmental authorisation process practitioner to facilitate the Stakeholder below. undertaken as a component of the stakeholder Engagement and to undertake the Basic Assessment process for the Robben Island § GN.R 983 Listing Notice 1: 1, 12, 15, 17 and 19 consultation process and is intended to provide stakeholders with adequate information on the project. Museum to obtain the required § GN.R 985 Listing Notice 3: 12 and 14 environmental authorisation. -

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa January 21 - February 2, 2012 Day 1 Saturday, January 21 3:10pm Depart from Minneapolis via Delta Air Lines flight 258 service to Cape Town via Amsterdam Day 2 Sunday, January 22 Cape Town 10:30pm Arrive in Cape Town. Meet your MCI Tour Manager who will assist the group to awaiting chartered motorcoach for a transfer to Protea Sea Point Hotel Day 3 Monday, January 23 Cape Town Breakfast at the hotel Morning sightseeing tour of Cape Town, including a drive through the historic Malay Quarter, and a visit to the South African Museum with its world famous Bushman exhibits. Just a few blocks away we visit the District Six Museum. In 1966, it was declared a white area under the Group areas Act of 1950, and by 1982, the life of the community was over. 60,000 were forcibly removed to barren outlying areas aptly known as Cape Flats, and their houses in District Six were flattened by bulldozers. In District Six, there is the opportunity to visit a Visit a homeless shelter for boys ages 6-16 We end the morning with a visit to the Cape Town Stadium built for the 2010 Soccer World Cup. Enjoy an afternoon cable car ride up Table Mountain, home to 1470 different species of plants. The Cape Floral Region, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is one of the richest areas for plants in the world. Lunch, on own Continue to visit Monkeybiz on Rose Street in the Bo-Kaap. The majority of Monkeybiz artists have known poverty, neglect and deprivation for most of their lives. -

Revised Appeals Agenda 15 July 2020 Ab WD SB.Pdf

AGENDA APPEALS MEETING OF HERITAGE WESTERN CAPE APPEALS COMMITTEE TO BE HELD ON WEDNESDAY, 15 July 2020 at 9H00. Please note due to the lockdown, the meeting will be held via Microsoft Teams (https://teams.microsoft.com/downloads) To be a participant in the meeting, kindly email the item and contact details to [email protected] ahead of the scheduled time. Agenda No. Case number Item Reference No Documents to be tabled Matter Heritage Officer 1 Opening 2 Attendance 3 Apologies 4 Approval of Agenda 4.1 Dated: 15 July 2020 5. Approval of Pevious Minutes 5.1 Dated: 17 June 2020 6 Disclosure of Interest 7 Confidential Matters 8 Administrative Matters 8.1 Outcome of Tribunal Committee and Recent Court Decisions 8.2 Report back from HWC Council 8.3 Site Visits Conducted 8.3.1 None 8.4 Potential Site Visits 8.4.1 None MATTERS TO BE DISCUSSED Agenda No. Case number Item Reference No Documents to be tabled Matter Heritage Officer 9 MATTERS ARISING SECTION 34 MATTER FROM BELCOM Proposed demolition and partial demolition of various structure on - Erf HM/ROHM/ CAPE TOWN METROPOLITAN/ 9.1 19091609WD1129E 32564, Athlone Power Station, Corner Bhunga Avenue and N1 Highway Appeal documentation Matters Arising Waseefa Dhansay ATHLONE/ERF 32564NDEBOSCH / ERF 45530 Athlone SECTION 34 MATTER FROM BELCOM Appeal - Additions and Alterations - Erf 68058, 4 Smithers Road, HM/ CAPE TOWN METROPOLITAN/ KENILWORTH/ ERF 9.2 119110410WD1106E Revised propsal Matters Arising Waseefa Dhansay Kenilworth 68058 SECTION 34 MATTER FROM BELCOM/TRIBUNAL Proposed -

1 Additional Analysis on SAPS Resourcing for Khayelitsha

1 Additional analysis on SAPS resourcing for Khayelitsha Commission Jean Redpath 29 January 2014 1. I have perused a document labelled A3.39.1 purports to show the “granted” SAPS Resource Allocation Guides (RAGS) for 2009-2011 in respect of personnel, vehicles and computers, for the police stations of Camps Bay, Durbanville, Grassy Park, Kensington, Mitchells Plain, Muizenberg, Nyanga, Philippi and Sea Point . For 2012 the document provides data on personnel only for the same police stations. 2. I am informed that RAGS are determined by SAPS at National Level and are broadly based on population figures and crime rates. I am also informed that provincial commissioners frequently make their own resource allocations, which may be different from RAGS, based on their own information or perceptions. 3. I have perused General Tshabalala’s Task Team report which details the allocations of vehicles and personnel to the three police stations of Harare, Khayelitsha and Lingelethu West in 2012. It is unclear whether these are RAGS figures or actual figures. I have combined these figures with the RAGS figures in the document labelled A3.39.1 in the tables below. 4. I have perused documents annexed to a letter from Major General Jephta dated 13 Mary 2013 (Jephta’s letter). The first annexed document purports to show the total population in each police station for all police stations in the Western Cape (SAPS estimates). 5. Because the borders of Census enumerator areas do not coincide exactly with the borders of policing areas there may be slight discrepancies between different estimates of population size in policing areas. -

For the Demolition of No.19 and 17 Kloof Road, Sea Point on Erven 391 and 392 Fresnaye

Heritage Statement to accompany an application for a permit i.t.o. Section 34 of the NHRA (Act 25 of 1999) for the demolition of No.19 and 17 Kloof Road, Sea Point on Erven 391 and 392 Fresnaye The subject building from the west, across Kloof Road, with No.17 on the left and No.19 on the right. April 2016 Frik Vermeulen Pr. Pln BTech TRP (CTech) MPhil CBE (UCT) MSAPI MAPHP Professional Heritage Practitioner TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Location and Context 3. Historical Background 3.1 Brief Development History of Sea Point 3.2 History and Development of the Subject Site 4. Description 4.1 Erf 391 (No.19 Kloof Road) 4.2 Erf 392 (No.17 Kloof Road) 5. Statement of Significance 6. Consultation undertaken 7. Conclusion ANNEXURES SG Diagram: Erf 391 Fresnaye SG Diagram: Erf 392 Fresnaye Summary Sheet: No.19 Kloof Road (Erf 391) Summary Sheet: No.17 Kloof Road (Erf 392) Comment from Sea Point Fresnaye Bantry Bay Ratepayers and Residents Association Comment from City of Cape Town’s Environmental and Heritage Management Branch 1 1. Introduction The author has been appointed by K2013204008 (Pty) Ltd, the owner of Erven 391 and 392 Fresnaye, to make application for the total demolition of these two semi-detached houses. Since the building, which contains fabric dating back to c1890, is older than 60 years, a permit is required from Heritage Western Cape in terms of Section 34(1) of the National Heritage Resources Act (25 of 1999). It is proposed to redevelop the site and utilise the development opportunities offered by its strategic location and its General Business GB5 zoning, with a floor factor of 4.0 and permissible height of 25m. -

Film Locations in TMNP

Film Locations in TMNP Boulders Boulders Animal Camp and Acacia Tree Murray and Stewart Quarry Hillside above Rhodes Memorial going towards Block House Pipe Track Newlands Forest Top of Table Mountain Top of Table Mountain Top of Table Mountain Noordhoek Beach Rocks Misty Cliffs Beach Newlands Forest Old Buildings Abseil Site on Table Mountain Noordhoek beach Signal Hill Top of Table Mountain Top of Signal Hill looking towards Town Animal Camp looking towards Devils Peak Tafelberg Road Lay Byes Noordhoek beach with animals Deer Park Old Zoo site on Groote Schuur Estate : External Old Zoo Site Groote Schuur Estate ; Internal Oudekraal Oudekraal Gazebo Rhodes Memorial Newlands Forest Above Rhodes Memorial Rhodes Memorial Rhodes Memorial Rhodes Memorial Rhodes Memorial Kramat on Signal Hill Newlands Forest Platteklip Gorge on the way to the top of Table Mountain Signal Hill Oudekraal Deer Park Misty Cliffs Misty Cliffs Tracks off Tafelberg Road coming down Glencoe Quarry Buffels Bay at Cape Point Silvermine Dam Desk on Signal Hill Animal Camp Cecelia Forest Cecelia Forest Cecilia Forest Buffels Bay at Cape Point Link Road at Cape Point Cape Point at the Lighthouse Precinct Acacia Tree in the Game camp Slangkop Slangkop Boardwalk near Kommetjie Kleinplaas Dam Devils Peak Devils Peak Noordhoek LookOut Chapmans Peak Noordhoek to Hout Bay Dias Beach at CapePoint Cape Point Cape Point Oudekraal to Twelve Apostles Silvermine Dam . -

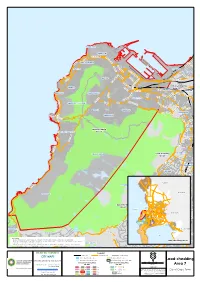

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

EMP) for Road Cycling and Mountain Biking: Table Mountain National Park (TMNP

Revision of the 2002 Environmental Management Programme (EMP) for Road Cycling and Mountain Biking: Table Mountain National Park (TMNP) compiled by SANParks and Table Mountain Mountain Bike Forum (TMMTB Forum) Draft for Public Comment MARCH 2016 Revision of the 2002 Environmental Management Programme – Cycling (Road and Mountain Bike) Document for Public Comment This document is the draft of the Revision of the 2002 Environmental Management Programme (EMP) for Road Cycling and Mountain Biking in the Table Mountain National Park. This document is an opportunity for interested parties, stakeholders and authorities to provide information and comment on this first draft which sets out how cycling will be managed in the Park. Where to find the EMP: Electronic copies, along with high resolution maps are available from the following websites: www.tmnp.co.za, www.TMMTB.co.za, www.pedalpower.org.za, www.amarider.org.za, www.tokaimtb.co.za Hard copies of the draft EMP have been placed at the following public libraries: Athlone Public Library Bellville Public Library Cape Town: Central Library Claremont Public Library Fish Hoek Public Library Grassy Park Public Library Gugulethu Public Library Hout Bay Public Library Khayelitsha Public Library Langa Public Library Mitchell's Plain Town Centre Library Mowbray Public Library Simon’s Town Public Library Tokai Public Library and the following Park offices: Boulders – Tokai Manor Kloofnek Office – Silvermine Office Simons Town House – Tokai Cape Town - Silvermine To ensure your submission is as effective as possible, please provide the following: • include name, organisation and contact details; • comment to be clear and concise; • list points according to the subject or sections along with document page numbers; • describe briefly each subject or issue you wish to raise; Comment period The document is open for comment from 04 April 2016 to 04 May 2016 Where to submit your comments [email protected] For attention: Simon Nicks Or, delivered to TMNP Tokai Manor Park office by 04th May 2016. -

Tygerberg News Magazine

TYGERBERG NEWS December 2017 | Volume 3| No. 3 Magazine IN THIS ISSUE COMPLIMENTS 2 Compliment & THANK YOU’S 3 CEO Message AWARENESS 6 IPC Day THANK YOU WARD D4 STAFF 7 Diabetes Day 9 Preemie Day Thank you to Sister Isaacs and Botes for the 10 Water savings idea hospitality and care. The room in Ward D4 (Bed No 11) was EVENTS clean, bathroom floor clean which made 4 Hartman Nursing Awards the process easier. STAFF RECOGNITION Sister Botes thank you making us feel 8 CMA Nominee calm and showing the motherhood 11 Mr Fransman characteristics. We appreciate the positive energy and your warm smile. May God bless the staff that assisted me on 13 TYGERBERG HOSPITAL November during admission and during MAGAZINE TEAM: the procedure on 14 November. Telephone: 021 938 5454/5608 Fax: 086 601 5218 We will come back to show you our children soon. We really appreciate E-mail: all you’ve done for us. Compliments to [email protected] [email protected] the Chef, the food was delicious and nutritious. The Kitchen was also clean, All letters, suggestions and articles thank you to the cleaning staff. May you can be sent to the above email or fax continue to do this to others too. Lastly number. Note that all photos must be high resolution (good quality) . thank you to the Theatre staff for the job well done. God bless in abundance. Mr Jerome, thank you for everything. I love your jazz music. Mr & Mrs Feldman CONTENTS 2 | TYGERBERG NEWS MESSAGE From the CEO.. -

The Great Green Outdoors

MAMRE CITY OF CAPE TOWN WORLD DESIGN CAPITAL CAPE TOWN 2014 ATLANTIS World Design Capital (WDC) is a biannual honour awarded by the International Council for Societies of Industrial Design (ICSID), to one city across the globe, to show its commitment to using design as a social, cultural and economic development tool. THE GREAT Cape Town Green Map is proud to have been included in the WDC 2014 Bid Book, 2014 SILWERSTROOMSTRAND and played host to the International ICSID judges visiting the city. 01 Design-led thinking has the potential to improve life, which is why Cape WORLD DESIGN CAPITAL GREEN OUTDOORS R27 Town’s World Design Capital 2014’s over-arching theme is ‘Live Design. Transform Life.’ Cape Town is defi nitively Green by Design. Our city is one of a few Our particular focus has become ‘Green by Design’ - projects and in the world with a national park and two World Heritage Sites products where environmental, social and cultural impacts inform (Table Mountain National Park and Robben Island) contained within design and aim to transform life. KOEBERG NATURE its boundaries. The Mother City is located in a biodiversity hot Green Map System accepted Cape Town’s RESERVE spot‚ the Cape Floristic Region, and is recognised globally for its new category and icon, created by Design extraordinarily rich and diverse fauna and fl ora. Infestation – the fi rst addition since 2008 to their internationally recognised set of icons. N www.capetowngreenmap.co.za Discover and experience Cape Town’s natural beauty and enjoy its For an overview of Cape Town’s WDC 2014 projects go to www.capetowngreenmap.co.za/ great outdoor lifestyle choices. -

Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010

Then and Now: Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010 Julian A Jacobs (8805469) University of the Western Cape Supervisor: Prof Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie Masters Research Essay in partial fulfillment of Masters of Arts Degree in History November 2010 DECLARATION I declare that „Then and Now: Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010‟ is my own work and that all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. …………………………………… Julian Anthony Jacobs i ABSTRACT This is a study of activists from Manenberg, a township on the Cape Flats, Cape Town, South Africa and how they went about bringing change. It seeks to answer the question, how has activism changed in post-apartheid Manenberg as compared to the 1980s? The study analysed the politics of resistance in Manenberg placing it within the over arching mass defiance campaign in Greater Cape Town at the time and comparing the strategies used to mobilize residents in Manenberg in the 1980s to strategies used in the period of the 2000s. The thesis also focused on several key figures in Manenberg with a view to understanding what local conditions inspired them to activism. The use of biographies brought about a synoptic view into activists lives, their living conditions, their experiences of the apartheid regime, their brutal experience of apartheid and their resistance and strength against a system that was prepared to keep people on the outside. This study found that local living conditions motivated activism and became grounds for mobilising residents to make Manenberg a site of resistance. It was easy to mobilise residents on issues around rent increases, lack of resources, infrastructure and proper housing.