“Why Not Us?”: Lisa Kron on 9/11 and in the Wake by Julie Haverkate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SOUND INSIDE a New Play by Pulitzer Prize Finalist ADAM RAPP Directed by Tony Award Winner DAVID CROMER

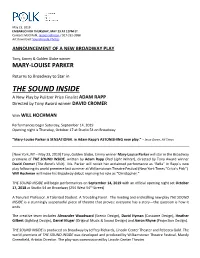

May 23, 2019 EMBARGO FOR THURSDAY, MAY 23 AT 12PM ET Contact: Matt Polk, Jessica Johnson / 917-261-3988 Art Download: Sound Inside Photos ANNOUNCEMENT OF A NEW BROADWAY PLAY Tony, Emmy & Golden Globe winner MARY-LOUISE PARKER Returns to Broadway to Star in THE SOUND INSIDE A New Play by Pulitzer Prize Finalist ADAM RAPP Directed by Tony Award winner DAVID CROMER With WILL HOCHMAN Performances begin Saturday, September 14, 2019 Opening night is Thursday, October 17 at Studio 54 on Broadway “Mary-Louise Parker is SENSATIONAL in Adam Rapp’s ASTONISHING new play.” – Jesse Green, NY Times [New York, NY – May 23, 2019] Tony, Golden Globe, Emmy winner Mary-Louise Parker will star in the Broadway premiere of THE SOUND INSIDE, written by Adam Rapp (Red Light Winter), directed by Tony Award winner David Cromer (The Band’s Visit). Ms. Parker will revisit her acclaimed performance as “Bella” in Rapp’s new play following its world premiere last summer at Williamstown Theatre Festival (New York Times “Critic’s Pick”). Will Hochman will make his Broadway debut reprising his role as “Christopher.” THE SOUND INSIDE will begin performances on September 14, 2019 with an official opening night set October 17, 2018 at Studio 54 on Broadway (254 West 54th Street). A Tenured Professor. A Talented Student. A Troubling Favor. The riveting and enthralling new play THE SOUND INSIDE is a stunningly suspenseful piece of theatre that proves: everyone has a story—the question is how it ends. The creative team includes Alexander Woodward (Scenic Design), David Hyman (Costume Design), Heather Gilbert (Lighting Design), Daniel Kluger (Original Music & Sound Design) and Aaron Rhyne (Projection Design). -

City Theatre Announces 2020-21 Season

CONTACT: Nikki Battestillli Marketing Director 412-431-4400 x230 [email protected] CityTheatreCompany.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CITY THEATRE ANNOUNCES 2020-21 SEASON Frankenstein – by Manual Cinema Paradise Blue – by Dominique Morisseau The Sound Inside – by Adam Rapp Vietgone – by Qui Nguyen The Garbologists – by Lindsay Joelle – (World Premiere) Title TBA – by James McManus – (World Premiere) Pittsburgh, PA (March 1, 2020). City Theatre Company, Pittsburgh’s home for contemporary plays, has announced the details of the theatre’s 46th season of new works. “Our job as a new works theater is to keep our audience engaged with the national theater landscape.” commented Artistic Director Marc Masterson. “We are proud to present a season that brings back City Theatre favorites, introduces new voices, and adds a Pittsburgh story into the American theater canon.” In addition to a six-play subscription series, the 2020/21 season will also feature the return of THE BASH (City’s signature block party fundraiser on Saturday, September 12, 2020), the Young Playwrights Festival, the Momentum Festival, and the Momentum Reading Series, along with numerous special events and partnership activities through its innovating community engagement initiative, City Connects. City Theatre will also ring in the holidays with an all-new, original show from the creative team behind this year’s hit Santa’s Ted Talk. Details to be announced. ABOUT THE PLAYS: We launch with Frankenstein by Manual Cinema which has been called “a complex visual treat…impressive in scope and execution, entertaining, and absolutely fascinating to watch,” by Chicago on Stage. The season continues with the return of two City Theatre favorites: Dominique Morisseau (Sunset Baby, Pipeline), with her play Paradise Blue, part of her Detroit trilogy, and Adam Rapp’s The Sound Inside, which just closed on Broadway starring Mary Louise Parker. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Dafina Mcmillan January 31, 2014 [email protected] 212-609-5955

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Dafina McMillan January 31, 2014 [email protected] 212-609-5955 New from TCG Books: The Hallway Trilogy by Adam Rapp NEW YORK, NY – Theatre Communications Group (TCG) is pleased to announce the publication of The Hallway Trilogy by Adam Rapp, the author of the Pulitzer Prize-finalist, Red Light Winter. This harrowing series weaving tales of love, torment and redemption received its world premiere at New York City’s Rattlestick Playwrights Theater in February 2011. “To watch The Hallway Trilogy by Adam Rapp is to enter an alternate universe…a carnival of the desperate, the grotesque, the outrageous.” — New York Times Playwright provocateur Adam Rapp weaves tales of love, torment and redemption in The Hallway Trilogy, a dark and compelling exploration of what binds people together and drives them apart. Spanning 100 years in a Lower East Side tenement hallway, The Hallway Trilogy of connected plays begins in 1953 with Rose, in which a young, troubled actress searches for affirmation from the one person who has shown her a bit of kindness – the great playwright Eugene O’Neill. Fifty years later in Paraffin, an unhappily married couple is thrown together with a paralyzed war veteran, a bungling super and other lost souls searching to connect during the 2003 blackout. Nursing dramatizes a horrifying future: In 2053, the hallway is now a museum in which the financially desperate are injected with obsolete diseases for the amusement of a public that doesn’t know what it means to suffer, or to love. “I knew in a single sentence that Adam was a writer the world was going to listen to for as long as he felt like writing…Adam writes like nobody else, his fierce poetic power as inescapable as the doom that waits for his characters. -

Almost in Love

ALMOST IN LOVE a love story in two takes Cast Alex Karpovsky – Sasha Gary Wilmes – Kyle Marjan Neshat – Mia Alan Cumming – Hayden Adam Rapp – Lee Katherine Waterston – Lulu Crew Sam Neave – Writer/Director Daniel McKeown – Camera Michaela McKee – Producer DL Glickman - Producer The glance reveals what the gaze obscures Ralph Waldo Emerson Synopsis A love story shot in two single, continuous 40 minute takes set eighteen months apart: the first over a sunset, the second over a sunrise. Sasha has been in love with Mia for years. His best friend, Kyle, recently started dating Mia until it all fell apart. None of them have spoken for over a month when Sasha hosts a barbecue on his Staten Island terrace - but that’s all about to change. Over the course of the evening in New York and a drunken dawn in the Hamptons the three of them show just how far they will go for love, for themselves and for each other. The story of a love triangle in two uninterrupted halves, Almost in Love mixes a naturalistic style with an ambitious new form to create a unique experience. A film that deals with loyalty, friendship and love - and whether a perfect moment can save us from ourselves. It may seem perverse for a man who makes his living as an editor to try to make a film essentially without edits but Almost in Love is my attempt to combine the natural intimacy and improvisatory style that I love with a more rigorous formal aesthetic. I wanted to see if we could perform this technical sleight-of-hand without sacrificing the emphasis that I tend to place on the actors. -

Loitering with Intent Free

FREE LOITERING WITH INTENT PDF Stuart Woods | 389 pages | 24 Nov 2009 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780451228567 | English | New York, United States Loitering with Intent (film) - Wikipedia Looking for a movie the entire family can enjoy? Check out our picks for family friendly movies movies that transcend all ages. For even more, visit our Family Entertainment Guide. See the full list. Title: Loitering with Intent They end up making a big shot producer think that they have a hot script that everyone wants to get their hands on. The 2 men then drive to upstate New York and hole up in a family member's country home- with 10 dedicated days to write said script. Dominic and Raphael then get derailed by a beautiful gardener, Ava and Dominic's sister, Gigi. Both women appear at the house, which was supposed to be serene enough to focus on the task at hand. But to add to the problems, Gigi's boyfriend Wayne arrives, still suffering from PTSD, and his brother Devon as well, creating even more havoc. A looming deadline and complicated personal histories create scenes that are humorous and emotional. Written by Liora P. Looking for something to watch? Choose an adventure below and discover your Loitering with Intent favorite movie or Loitering with Intent show. Visit our What to Watch page. Sign In. Keep track of everything you watch; tell your friends. Full Cast and Crew. Release Dates. Official Sites. Company Credits. Technical Specs. Plot Loitering with Intent. Plot Keywords. Parents Guide. External Sites. User Reviews. User Ratings. External Reviews. -

Nlegel Smlth ARTISTIC DIRECTOR CAROL OSTROW PRODUCING

THE FLEA THEATER NIEGEL SMITH ARTISTIC DIRECTOR CAROL OSTROW PRODUCING DIRECTOR PRESENTS THE AMERICAN PREMIERE OF WOLF IN THE RIVER WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY ADAM RAPP WITH ADDITIONAL TEXT BY THE BATS FEATURING THE BATS WILLIAM APPS, MAKI BORDEN, ALEXANDRA CURRAN, KAREN EILBACHER, KRISTIN FRIEDLANDER, JACK HORTON GILBERT, JOHN PAUL HARKINS, OLIVIA JAMPOL, ARTEM KREIMER, DEREK CHRISTOPHER MURPHY, MIKE SWIFT, KATE THULIN, CASEY WORTMANN ARNULFO MALDONADO SCENIC DESIGN MASHA TSIMRING LIGHTING DESIGN MICHAEL HILI & HALLIE ELIZABETH NEWTON COSTUME DESIGN BRENDAN COnnELLY & LEE KInnEY SOUND DESIGN ZACH SERAFIN PROPS MASTER J. DAVID BRIMMER FIGHT CHOREOGRAPHY SARAH EAST JOHnsON AERIAL CONSULTANT AnsHUMAN BHATIA ASSISTANT SCENIC DESIGN BEckY HEISLER ASSISTANT LIGHTING DESIGN AnnE CECELIA HANEY ASSISTANT DIRECTOR MORGAN LEIGH BEACH STAGE MANAGER AnnIE JEnkIns ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER BRADLEY MEAD/WIIDE GRAPHIC DESIGNER RON LAskO/SPIN CYCLE PRESS REPRESENTATIVE CAST The Woman ...................................................................... Olivia Jampol Tana ....................................................................................Kate Thulin Debo ................................................................................. Maki Borden Dothan .............................................................................William Apps Monty ..................................................................... Kristin Friedlander Aikin ............................................................................Karen Eilbacher Pin........................................................................................Mike -

FORGETTING the GIRL a Film by Nate Taylor

presents FORGETTING THE GIRL A film by Nate Taylor “[A] nuanced, image driven film… written with a poet’s ear and directed with an artist’s eye.” -Annlee Ellingson, The LA Times “A psycho-sexual thriller [that’s] a pleasant surprise!” -Joe Leydon, Variety USA / 2012 / Thriller / English / Not Rated 85 min / 2.35:1 / 5.1 Surround Official Film Webpage RAM Releasing Press Contact: Lisa Trifone | 109 W. 27th Street, Suite 9B | New York, NY 10001 tel: (212) 941-7744 x 209 | fax: (212) 941-7812 | [email protected] RAM Releasing Theatrical Contact: Rebeca Conget | 109 W. 27th Street, Suite 9B | New York, NY 10001 tel: (212) 941-7744 x 213 | fax: (212) 941-7812 | [email protected] FULL SYNOPSIS Kevin is obsessed with finding a girl who can help him forget his unpleasant past. However, all his encounters with the opposite sex inevitably go afoul, creating more awkward experiences than he can cope with. As the rejections mount, Kevin’s futile search for happiness and love becomes overwhelmingly turbulent, forcing him to take desperate measures. Shot in a variety of NYC locales, from Hell’s Kitchen to Greenpoint, Forgetting the Girl is a gritty vision of the city and its denizens. The tightly-woven drama blends recollections with reality to craft an intense character study of the psychologically-scarred protagonist. As beautiful as it is dark, the tense narrative slowly boils under the surface until it unleashes an unsettling climax that will not be easily forgotten. ASSETS Official trailer for embedding/sharing: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XcHL5lF5UQg Downloadable hi-res images: http://www.ramreleasing.com/press DIRECTOR’S NOTES I got chills up my spine the first time I read the Forgetting the Girl script. -

View Program

May 2021 Owen Theatre The Sound Inside C1 contents Managing Editor: Jaclyn Jermyn features Editors: Neena Arndt Denise Schneider 2 A Note from the Executive Director Graphic Designer: Alma D'Anca 5 Back in the Director's Chair Goodman Theatre 7 Life Story 170 N. Dearborn St. Chicago, IL 60601 9 Open Book Box Office: 312.443.3800 Admin Offices: 312.443.3811 the production 12 The Sound Inside Chicago's theater since 1925, 14 Artist Profiles Goodman Theatre is a not-for-profit arts and community organization in the heart of the Loop, distinguished by the the theater excellence and scope of its artistic programming and civic 20 About Goodman Theatre engagement. Learn more at 21 Staff GoodmanTheatre.org. 24 Leadership 27 Support OPEN-CAPTIONED PERFORMANCE Sunday, May 16 at 2pm Open Captioning is provided by c2. c2 pioneered and specializes in live theatrical and performance captioning for patrons with all degrees of hearing loss. With a national presence and over 700 shows per year, c2 works with prestigious theatres on Broadway, off-Broadway, with national touring houses, and top-shelf regional theatres across the country, including many in Chicago. welcome There’s nothing like the thrill of live theater. The emotions are heightened, the experience is dazzling, and, in what feels like an instant, it’s a memory. There’s no rewinding. There are no do- overs. This feeling is what draws so many of us to the theater— and it’s what we have collectively been missing over the past year, as our stages have been dark.