City of Huntington Beach General Plan Update Program Environmental Impact Report SCH No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

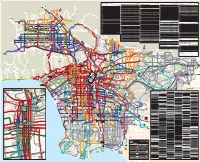

Metro Bus and Metro Rail System

Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Metro Bus Lines East/West Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays North/South Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Limited Stop Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Special Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Approximate frequency in minutes Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Weekdays Saturdays Sundays 102 Walnut Park-Florence-East Jefferson Bl- 200 Alvarado St 5-8 11 12-30 10 12-30 12 12-30 302 Sunset Bl Limited 6-20—————— 603 Rampart Bl-Hoover St-Allesandro St- Local Service To/From Downtown LA 29-4038-4531-4545454545 10-12123020-303020-3030 Exposition Bl-Coliseum St 201 Silverlake Bl-Atwater-Glendale 40 40 40 60 60a 60 60a 305 Crosstown Bus:UCLA/Westwood- Colorado St Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve 3045-60————— NEWHALL 105 202 Imperial/Wilmington Station Limited 605 SANTA CLARITA 2 Sunset Bl 3-8 9-10 15-30 12-14 15-30 15-25 20-30 Vernon Av-La Cienega Bl 15-18 18-20 20-60 15 20-60 20 40-60 Willowbrook-Compton-Wilmington 30-60 — 60* — 60* — —60* Grande Vista Av-Boyle Heights- 5 10 15-20 30a 30 30a 30 30a PRINCESSA 4 Santa Monica Bl 7-14 8-14 15-18 12-18 12-15 15-30 15 108 Marina del Rey-Slauson Av-Pico Rivera 4-8 15 18-60 14-17 18-60 15-20 25-60 204 Vermont Av 6-10 10-15 20-30 15-20 15-30 12-15 15-30 312 La Brea -

News Release

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION News Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Roy Stearns May 22, 2009 (916) 654-7538 California State Parks Named in ReserveAmerica’s “Top 100 Family Campgrounds” Awards Program California State Parks were named in ReserveAmerica’s “Top 100 Family Campgrounds” awards program. ReserveAmerica, a leading recreation reservation and campground management company, announced the winners of their annual “Top 100 Family Campgrounds” awards program. The winning parks were selected based on testimonials, campground ratings and feedback provided by park rangers, regional park management and campers throughout the year. Campgrounds were determined on specific family-friendly criteria ranging from educational programs and visitor centers to camping amenities and overall beauty and scenery. Other factors considered included the quality and availability of hot showers, laundry facilities, hiking trails, family beaches, radio-free zones, visitor centers, educational programs, children’s events and location. Here are the California State Parks chosen in the awards program: 2009 Top 100 Family Campgrounds Anza-Borrego Desert State Park-San Diego, CA Castle Crags State Park-Shasta, CA Millerton Lake State Recreation Area-Fresno, CA Morro Bay State Park-San Luis, CA Sonoma Coast State Beach-Sonoma, CA Top 25 Amazing Spots San Simeon State Park-Cambria, CA Top 25 Biking Trails Cuyamaca Rancho State Park-San Diego, CA (more) For energy efficient recreation - California State Parks on the Internet: <http://www.parks.ca.gov> -

Doggin' America's Beaches

Doggin’ America’s Beaches A Traveler’s Guide To Dog-Friendly Beaches - (and those that aren’t) Doug Gelbert illustrations by Andrew Chesworth Cruden Bay Books There is always something for an active dog to look forward to at the beach... DOGGIN’ AMERICA’S BEACHES Copyright 2007 by Cruden Bay Books All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the Publisher. Cruden Bay Books PO Box 467 Montchanin, DE 19710 www.hikewithyourdog.com International Standard Book Number 978-0-9797074-4-5 “Dogs are our link to paradise...to sit with a dog on a hillside on a glorious afternoon is to be back in Eden, where doing nothing was not boring - it was peace.” - Milan Kundera Ahead On The Trail Your Dog On The Atlantic Ocean Beaches 7 Your Dog On The Gulf Of Mexico Beaches 6 Your Dog On The Pacific Ocean Beaches 7 Your Dog On The Great Lakes Beaches 0 Also... Tips For Taking Your Dog To The Beach 6 Doggin’ The Chesapeake Bay 4 Introduction It is hard to imagine any place a dog is happier than at a beach. Whether running around on the sand, jumping in the water or just lying in the sun, every dog deserves a day at the beach. But all too often dog owners stopping at a sandy stretch of beach are met with signs designed to make hearts - human and canine alike - droop: NO DOGS ON BEACH. -

11-07-19-Board-Packet-1.Pdf

Long Beach Transit welcomes you to this meeting and invites you to participate in matters before the Board. Information and Procedures Concerning Conduct at Board of Directors’ Meetings PUBLIC PARTICIPATION: SPECIAL PRESENTATIONS: All members of the public may address the Board on any Special presentations which include slides, video, etc., item listed on the agenda. during the course of a meeting will only be allowed when All members of the public may address the Board on non- requested of the Board Secretary eight days in advance of agenda items from “Business From The Floor.” the meeting, which will require prior approval from the Chair. Each speaker will be asked to complete a Speaker Card and turn it in to the Board Secretary prior to the conclusion BUSINESS FROM THE FLOOR: of the staff presentation and will state his/her name at the podium before speaking. A member of the general public may address the Board on any matter not appearing on the agenda that is of interest Persons demonstrating rude, bois- to such person and within the jurisdiction of the terous or profane behavior will be Board. called to order by the Chair. If such conduct continues, the Chair may No action can be taken by the Board on any call a recess, requesting the removal The Board of Directors items brought forward at this time. The Board of such person(s) from the Council and Staff shall work to may request this item be brought back at a Chamber, adjourn the meeting or subsequent meeting. take some other appropriate action. -

2020 Pacific Coast Winter Window Survey Results

2020 Winter Window Survey for Snowy Plovers on U.S. Pacific Coast with 2013-2020 Results for Comparison. Note: blanks indicate no survey was conducted. REGION SITE OWNER 2017 2018 2019 2020 2020 Date Primary Observer(s) Gray's Harbor Copalis Spit State Parks 0 0 0 0 28-Jan C. Sundstrum Conner Creek State Parks 0 0 0 0 28-Jan C. Sundstrum, W. Michaelis Damon Point WDNR 0 0 0 0 30-Jan C. Sundstrum Oyhut Spit WDNR 0 0 0 0 30-Jan C. Sundstrum Ocean Shores to Ocean City 4 10 0 9 28-Jan C. Sundstrum, W. Michaelis County Total 4 10 0 9 Pacific Midway Beach Private, State Parks 22 28 58 66 27-Jan C. Sundstrum, W. Michaelis Graveyard Spit Shoalwater Indian Tribe 0 0 0 0 30-Jan C. Sundstrum, R. Ashley Leadbetter Point NWR USFWS, State Parks 34 3 15 0 11-Feb W. Ritchie South Long Beach Private 6 0 7 0 10-Feb W. Ritchie Benson Beach State Parks 0 0 0 0 20-Jan W. Ritchie County Total 62 31 80 66 Washington Total 66 41 80 75 Clatsop Fort Stevens State Park (Clatsop Spit) ACOE, OPRD 10 19 21 20-Jan T. Pyle, D. Osis DeLaura Beach OPRD No survey Camp Rilea DOD 0 0 0 No survey Sunset Beach OPRD 0 No survey Del Rio Beach OPRD 0 No survey Necanicum Spit OPRD 0 0 0 20-Jan J. Everett, S. Everett Gearhart Beach OPRD 0 No survey Columbia R-Necanicum R. OPRD No survey County Total 0 10 19 21 Tillamook Nehalem Spit OPRD 0 17 26 19-Jan D. -

Long Beach Transit and Flixbus Partner to Provide Affordable, Long-Distance Transportation New Service to Las Vegas Starts March 21

CONTACT: Michael Gold Public Information Officer, Long Beach Transit 562.599.8534 (office) 562.444.5309 (cell) [email protected] Julie Alvarez, FlixBus 213.378.3917 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Long Beach Transit and FlixBus Partner to Provide Affordable, Long-Distance Transportation New Service to Las Vegas starts March 21 LONG BEACH, CALIF. (March 14, 2018) – Long Beach Transit today announced a partnership with FlixBus to provide affordable bus service to Las Vegas starting March 21. FlixBus, a European-based mobility company, selected Long Beach as one of its hubs for travel to add to its growing network of destinations. “Long Beach impressed us with its diversity, energy and very progressive transit policy. It’s probably the most FlixBus-compatible community in California,” said Pierre Gourdain, Managing Director for FlixBus USA. “We are thrilled to start the route there and looking to add many more connections in the future.” Utilizing LBT’s downtown First Street Transit Gallery between Long Beach Blvd. and Pine Avenue, customers can take FlixBus to Las Vegas by purchasing tickets through the FlixBus app or website. Customers can also buy tickets at LBT’s Transit and Visitor Information Center. FlixBus will also offer service to Coachella and Stagecoach music festivals in April. “Our partnership with FlixBus is another example of LBT connecting communities, both locally and beyond,” said LBT President and CEO, Kenneth McDonald. “Now, LBT customers can catch a bus to the Transit Gallery and then explore destinations outside California.” Most of LBT’s buses connect to the Transit Gallery. In addition, customers can connect to other destinations outside the area through the Los Angeles Metro Blue Line, FlyAway service to Los Angeles International Airport and through connections to Long Beach Airport. -

Hello. I'm Will Kempton, Chief Executive Officer of the Orange

Hello. I’m Will Kempton, Chief Executive Officer of the Orange County Transportation Authority. I am pleased and honored to share the 2009 OCTA Annual Report with you. In an effort to reduce paper costs and "go green," this year’s annual report has moved to an online format. We think you’ll enjoy its interactivity. As you are aware, 2009 was a challenging year for transportation funding. We faced obstacles that we never had before, and hopefully, never will again. In spite of these obstacles, OCTA made great strides improving our transportation network. Due to our efforts in 2009, the I-5 Gateway Project through Buena Park is nearing completion. As a shovel-ready project, the SR-91 Eastbound Lane Addition Project received federal stimulus dollars in the spring of last year under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act...and we broke ground in November. Our 34 cities and the county received a total of $78 million for local street and road improvements to reduce your commute time. As part of the Metrolink Service Expansion Program, design for track and infrastructure improvements was completed. We also finished final design for grade crossing safety enhancements, and construction began on projects in the cities of Orange and Anaheim. Conceptual design and environmental clearance are under way for ARTIC, Orange County’s premier transportation hub. Construction is scheduled to begin in 2011. With the loss of State Transit Assistance funding and declining sales tax revenues, it was an extremely challenging year for our bus system. In June, the OCTA Board of Directors declared a fiscal emergency resulting in significant bus service reductions that affected our customers and employees. -

City Council Agenda Consideration for Passenger Flights in And

RANCHO PALOS VERDES CITY COUNCIL MEETING DATE: 05/07/2019 AGENDA REPORT AGENDA HEADING: Consent Calendar AGENDA DESCRIPTION: Consideration and possible action to enter into a Professional Services Agreement with ABCx2, LLC to analyze passenger jets flights over and around the Rancho Palos Verdes airspace RECOMMENDED COUNCIL ACTION: (1) Approve a Professional Services Agreement with ABCx2, LLC in the amount of $30,500 to analyze passenger jets flights over and around the Rancho Palos Verdes airspace FISCAL IMPACT: The services provided under this contract shall not exceed $30,500, including no more than $3,000 for reimbursable expenses, and has been budgeted in the Planning Division’s Professional and Technical Services account. Amount Budgeted: $193,825 Additional Appropriation: N/A Account Number(s): 101-400-4120-5101 (GF – Professional/Technical Services in Planning Division) ORIGINATED BY: Robert Nemeth, Associate Planner REVIEWED BY: Ara Mihranian, AICP, Director of Community Development APPROVED BY: Doug Willmore, City Manager ATTACHED SUPPORTING DOCUMENTS: A. Professional Services Agreement between City of Rancho Palos Verdes and ABCx2, LLC (page A-1) B. ABCx2, LLC Proposal to Rancho Palos Verdes (page B-1) C. May 30, 2018 City Attorney letter to FAA (page C-1) D. July 13, 2018 FAA response letter to City Attorney (page D-1) BACKGROUND AND DISCUSSION: In March 2017, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) implemented its SoCal Metroplex project, which was a regional redesign of the airspace over Southern California. With respect to passenger jet departures from Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), the SoCal Metroplex project did not change established offshore flight routes near the Palos Verdes Peninsula. -

SUMMARY of BEACH FIRE RULES in CALIFORNIA! There Are Approximately 435 Beaches in the State of California ( Sitelist.Html)

!SUMMARY of BEACH FIRE RULES in CALIFORNIA! There are approximately 435 beaches in the State of California (http://www.beachcalifornia.com/ sitelist.html). Of these about 38 beaches allow fires (http://www.beachcalifornia.com/beach- !bonfires-california.html) . ! It appears that ONLY Carmel Beach allows unlimited numbers of fires and ONLY Carmel does !not require a designated fire pit! Two major new programs have been implemented to try to further manage this issue, one in the National Park Service at Ocean Beach and one at Newport Beach. They are outlined below. !Following that are the published beach fire rules from the remaining beaches, cities or counties. ! ! NPS PILOT PROJECT Ocean Beach Fire Revised Pilot Program On Friday, May 23 new regulations went into effect for fires on Ocean Beach. This follows a proposal announced on April 21, 2014 to implement a Revised Pilot Program for fires at Ocean Beach. The Revised Pilot includes changes to the existing program in order to address growing concern about the unsafe conditions resulting from these fires, and the unsustainable level of staff effort required to ensure public safety and compliance with regulations. Public feedback was received through May 16, 2014. Information about this Revised Pilot, which includes an impact assessment, response to public comments, amendment to the compendium, and copies of the data collection forms that will be used can be found on this webpage; click Document List on the left, then click on the document title to download. Changes to the Fire Program: - 12 new fire rings installed - Fires must be extinguished at 9:00 PM - Fires prohibited on all Spare the Air Days year-round - Data will be collected on compliance with regulations At the end of the Revised Pilot, once the data collected is evaluated, The National Park Service will determine the next steps for the fire program on Ocean Beach. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Assessing the Economic Benefits of Reductions in Marine Debris: a Pilot Study of Beach Recreation in Orange County, California

FINAL REPORT Assessing the Economic Benefits of Reductions in Marine Debris: A Pilot Study of Beach Recreation in Orange County, California FINAL | June 15, 2014 prepared for: Marine Debris Division National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration prepared by: Chris Leggett, Nora Scherer, Mark Curry and Ryan Bailey Industrial Economics, Incorporated 2067 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02140 And Timothy Haab Ohio State University Executive Summary Marine debris has many impacts on the ocean, wildlife, and coastal communities. In order to better understand the economic impacts of marine debris on coastal communities, the NOAA Marine Debris Program and Industrial Economics, Inc. designed a study that examines how marine debris influences people’s decisions to go to the beach and what it may cost them. Prior to this study, no work had directly assessed the welfare losses imposed by marine debris on citizens who regularly use beaches for recreation. This study aimed to fill that gap in knowledge. The study showed that marine debris has a considerable economic impact on Orange County, California residents. We found that: ● Residents are concerned about marine debris, and it significantly influences their decisions to go to the beach. They will likely avoid littered beaches and spend additional time and money getting to a cleaner beach or pursuing other activities. ● Avoiding littered beaches costs local residents millions of dollars each year. ● Reducing marine debris on beaches can prevent financial loss and provide economic benefits to residents. Marine debris is preventable, and the benefits associated with preventing it appear to be quite large. For example, the study found that reducing marine debris by 50 percent at beaches in Orange County could generate $67 million in benefits to Orange County residents for a threemonth period. -

An Assessment of the Transport of Southern California Stormwater Ocean Discharges ⇑ Peter A

Marine Pollution Bulletin xxx (2014) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Pollution Bulletin journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/marpolbul An assessment of the transport of southern California stormwater ocean discharges ⇑ Peter A. Rogowski a, , Eric Terrill a, Kenneth Schiff b, Sung Yong Kim c a Coastal Observing R&D Center, Marine Physical Laboratory, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, CA 92093-0214, USA b Southern California Coastal Water Research Project, Costa Mesa, CA, USA c Division of Ocean Systems Engineering, School of Mechanical, Aerospace and Systems Engineering, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon, Republic of Korea article info abstract Article history: The dominant source of coastal pollution adversely affecting the regional coastal water quality is the sea- Available online xxxx sonally variable urban runoff discharged via southern California’s rivers. Here, we use a surface transport model of coastal circulation driven by current maps from high frequency radar to compute two-year Keywords: hindcasts to assess the temporal and spatial statistics of 20 southern California stormwater discharges. Stormwater plumes These models provide a quantitative, statistical measure of the spatial extent of the discharge plumes Urban runoff in the coastal receiving waters, defined here as a discharge’s ‘‘exposure’’. We use these exposure maps Coastal discharge from this synthesis effort to (1) assess the probability of stormwater connectivity to nearby Marine Pro- Areas of Special Biological Significance tected Areas, and (2) develop a methodology to estimate the mass transport of stormwater discharges. Water quality Southern California The results of the spatial and temporal analysis are found to be relevant to the hindcast assessment of coastal discharges and for use in forecasting transport of southern California discharges.