Building an Effective Social Protection System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innovative Educator Experts

Innovative Educator Experts 2019-2020 The Microsoft Innovative Educator (MIE) Expert program is an exclusive program created to recognize global educator visionaries who are using technology to pave the way for their peers for better learning and student outcomes. Microsoft Innovative Educator Experts Names are sorted by region, then country, then last name. Table of Contents Contents Asia Pacific Region ............................................................................................................................................................. 6 Bangladesh ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Brunei .................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Cambodia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Indonesia .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Korea .................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

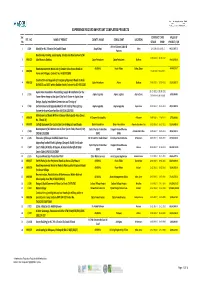

Experience Record Important Completed Projects

EXPERIENCE RECORD IMPORTANT COMPLETED PROJECTS Ser. CONTRACT DATE VALUE OF REF . NO . NAME OF PROJECT CLIENT'S NAME CONSULTANT LOCATION No STRART FINISH PROJECT / QR Artline & James Cubitt & 1 J/149 Masjid for H.E. Ghanim Bin Saad Al Saad Awqaf Dept. Dafna 12‐10‐2011/31‐10‐2012 68,527,487.70 Partners Road works, Parking, Landscaping, Shades and Development of Al‐ 22‐08‐2010 / 21‐06‐2012 2 MRJ/622 Jabel Area in Dukhan. Qatar Petroleum Qatar Petroleum Dukhan 14,428,932.00 Road Improvement Works out of Greater Doha Access Roads to ASHGHAL Road Affairs Doha, Qatar 48,045,328.17 3 MRJ/082 15‐06‐2010 / 13‐06‐2012 Farms and Villages, Contract No. IA 09/10 C89G Construction and Upgrade of Emergency/Approach Roads to Arab 4 MRJ/619 Qatar Petroleum Atkins Dukhan 27‐06‐2010 / 10‐07‐2012 23,583,833.70 D,FNGLCS and JDGS within Dukhan Fields,Contract No.GC‐09112200 Aspire Zone Foundation Dismantling, Supply & Installation for the 01‐01‐2011 / 30‐06‐2011 5 J / 151 Aspire Logistics Aspire Logistics Aspire Zone 6,550,000.00 Tower Flame Image at the Sport City Torch Tower in Aspire Zone Extension to be issued Design, Supply, Installation.Commission and Testing of 6 J / 155 Enchancement and Upgrade Work for the Field of Play Lighting Aspire Logestics Aspire Logestics Aspire Zone 01‐07‐2011 / 25‐11‐2011 28,832,000.00 System for Aspire Zone Facilities (AF/C/AL 1267/10) Maintenance of Roads Within Al Daayen Municipality Area (Zones 7 MRJ/078 Al Daayen Municipality Al Daayen 19‐08‐2009 / 11‐04‐2011 3,799,000.00 No. -

Hazm Mebaireek Hospital to Treat Covid-19 Cases

BUSINESS | Page 1 QATAR | Page 20 Ashghal implements preventive Qatar Airways Cargo to measures resume belly-hold cargo to combat operations to China virus spread published in QATAR since 1978 TUESDAY Vol. XXXXI No. 11504 March 31, 2020 Sha’ban 7, 1441 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Hazm Mebaireek Hospital to treat Covid-19 cases QNA Kaabi said that this decision is part of Doha the pre-emptive plan that the health- care sector is implementing to ensure that any possible increase in the number amad Medical Corporation of Covid-19 patients is managed. (HMC) has announced the des- He pointed out that Hazm Mebai- Hignation of Hazm Mebaireek reek General Hospital was specifi cally General Hospital as a facility for treat- chosen to treat Covid-19 patients be- ing coronavirus patients, with the aim cause the hospital will provide a mod- of providing high-quality care for such ern and advanced environment for the patients in an integrated facility. treatment of patients, both men and HE the Minister of Public Health Dr women of all nationalities. Hanan Mohamed al-Kuwari said that the Hazm Mebaireek General Hospital rapid transformation of Hazm Mebaireek has 147 beds, including 42 intensive General Hospital into a facility for treating care beds and 105 inpatient beds. coronavirus patients is an example of the The hospital’s capacity can be in- proactive approach in the healthcare sec- creased to 471 beds (221 beds for inten- tor in the face of this epidemic. sive care and 250 beds for inpatients). She added that the ministry started If needed in the future, it can also pro- to move quickly from the beginning vide a Covid-19 emergency depart- and worked to set standards through ment with a capacity of 150 beds. -

Quality of Service Measurements- Mobile Services Network Audit 2012

Quality of Service Measurements- Mobile Services Network Audit 2012 Quality of Service REPORT Mobile Network Audit – Quality of Service – ictQATAR - 2012 The purpose of the study is to evaluate and benchmark Quality Levels offered by Mobile Network Operators, Qtel and Vodafone, in the state of Qatar. The independent study was conducted with an objective End-user perspective by Directique and does not represent any views of ictQATAR. This study is the property of ictQATAR. Any effort to use this Study for any purpose is permitted only upon ictQATAR’s written consent. 2 Mobile Network Audit – Quality of Service – ictQATAR - 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 READER’S ADVICE ........................................................................................ 4 2 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................... 5 2.1 TEAM AND EQUIPMENT ........................................................................................ 5 2.2 VOICE SERVICE QUALITY TESTING ...................................................................... 6 2.3 SMS, MMS AND BBM MEASUREMENTS ............................................................ 14 2.4 DATA SERVICE TESTING ................................................................................... 16 2.5 KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS ...................................................................... 23 3 INDUSTRY RESULTS AND INTERNATIONAL BENCHMARK ........................... 25 3.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ -

Stratigraphy, Micropaleontology, and Paleoecology of the Miocene Dam Formation, Qatar

GeoArabia, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2002 Gulf PetroLink, Bahrain Miocene Dam Formation, Qatar Stratigraphy, micropaleontology, and paleoecology of the Miocene Dam Formation, Qatar Hamad Al-Saad and Mohamed I. Ibrahim University of Qatar ABSTRACT The Miocene carbonate Dam Formation is well exposed in the Jebel Al-Nakhash area of southern Qatar. Three sections were measured in a detailed investigation of the Formation’s stratigraphy, micropaleontology, and paleoecology. This biostratigraphic and paleoecologic study was supported by the analysis of microlithofacies and foraminiferal assemblages. Microfossils are predominantly benthic foraminifera represented by 38 species, many of which are milioline and one is a larger form. A Borelis melo melo Local Range Zone of Early Miocene (Burdigalian) age was recognized. The nature and distribution of the benthic foraminiferal assemblage, in association with lithofacies evidence, indicated a general shoaling-upward trend. The Dam Formation was stratigraphically subdivided into two new formal members. The basal Al-Kharrara Member is made up of limestone, marl, and claystone, and the overlying Al-Nakhash Member is a cyclic assemblage of carbonate, evaporite, and algal stromatolite facies. The lithofacies are grouped into four major types of which limestone, subdivided into six subfacies, is dominant. The Al-Kharrara was interpreted as having been deposited in warm (25°–30°C), clear, shallow waters of the inner neritic zone (0–35 m) that had an elevated salinity (35‰–50‰) and a vegetated substrate. The Al-Nakhash probably formed in an oscillating, very shallow-marine environment (0–10 m deep, including tidal flats), under warm climatic conditions that eventually led to the accumulation of evaporites and algal stromatolites. -

Penmagjuly242013

To advertise contact: Display - 44557 837 / 853 / 854 Classifieds - 44557 857 Fax: 44557 870 email: [email protected] 855 Classifieds Issue No. 1531 Wednesday, 24 July 2013 11 qatar home-4u Real Estate & Services Co. Homes 2 Rent British Managed Real Estate Company FOR RENT: LABOR ROOMS, STORES, OFFICES, SHOPS, VILLAS Commercial Offices Floor By Floor (670 SQM) Qrs.160/SQM We are able to offer over 500 property options to meet your requirements. All properties are available on short or long term lease. Free 24 hour Airport Road, Beside Al Mana Building maintenance, water and electricity, high speed internet, local telephone and cable Commercial Building Brand New for Offices TV. Weekly cleaning included if required. C-Ring Road, Floors = G+1+2, Size: 1,800 SQM, Qrs.250,000. 2 & 3 BEDROOM FULLY FURNISHED APARTMENT NEAR DESS Commercial Offices. Locations: Salwa Road & Airport Road QR.8,000-9,500 per month ref DH Sizes: 550 SQM, 180 SQM, 100 SQM FULLY FURNISHED SPACIOUS 2 BEDROOM APARTMENT (Showrooms / Shops) @ Salwa Road, Old Airport, Al Khor... etc. in Bin Mahmoud/Muntaza From QR.7,000 per month ref BM/GO Sizes: 1,000 SQM, 350 SQM, 100 SQM, 200 SQM 1 BEDROOM FULLY FURNISHED STUDIO APARTMENT WITH SWIMMING POOL Labor Accommodation Rooms are (200, 110, 80, 40, 20) in prestigious location, including daily cleaning, full-time watchman/cleaner, from QR.4,500 Industrial Area & Shahania: Qrs.1,500 up to 2,200. - 5,000 per month ref DG/WBC Labor Accommodation Rooms (50, 40, 60, 35) SPACIOUS 2 BEDROOM FULLY FURNISHED APARTMENTS in Madinat Khalifa/Bin Omran, From QR.7,000-8,500 per month ref JML/RSL/GS Locations: AlKhor, Sailiya, Al Wukair, Qrs.1,000 up to 1,500. -

Estado De Qatar

ESTADO DE QATAR DATOS BASICOS DEL ESTADO DE QATAR La península qatarí se adentra 150 km dentro del golfo Pérsico desde Arabia Saudita. El punto más alto de Qatar se encuentra en el Jebel Dukhan al oeste, una serie de bajos afloramientos de piedra caliza que corre de sur a norte desde Zikrit a través de Umm Bab hasta la frontera austral, y que alcanza alrededor de 90 metros sobre el nivel del mar. En esta zona también se encuentran los principales depósitos interiores de petróleo de Qatar, mientras que los yacimientos de gas natural están en el mar, al noroeste de la península. Nombre oficial: Estado de Qatar. Capital: Doha. Población: 885.359 (2009) División política: 10 provincias Ad daga, Al Ghuwariyah, Al Jumaliyah, Al Khawr, Al Wakrah, Ar Rayyan, Jariyan al Batnah, Ash Shamal, Umm Salal y Mesaieed. Países colindantes: se encuentra junto al Golfo Pérsico, entre Bahrein y los Emiratos Árabes Unidos. Ciudades principales: Al-Rayyan, Al-Wakrah y Umm Salal. Fecha de independencia: 3 de Septiembre 1971 del R.U.. Establecimiento de relaciones diplomáticas con México: 30 de junio 1975. Gentilicio: qatarí Superficie: 11.521 km 2 Idioma: árabe Clima: desértico. Religión: el islamismo es la religión oficial. Principales grupos étnicos: la población autóctona, de origen árabe, es minoritaria en relación al total, representa el 20%. Los árabes como grupo étnico, sin embargo, son mayoría gracias a la inmigración: 25% del total son palestinos, egipcios y yemenitas. El 55% restante está formado por inmigrantes pakistaníes, iraníes e indios orientales y otros. ESTADO DE QATAR INDICADORES ECONOMICOS Moneda: rial qatarí Tipo de cambio: 1 US Dólar = 3.64075 Rial de Qatar (3/02/10) PIB per cápita: 81.861 Dólares EUA (est.) (2009) Crecimiento anual: 11,2 % (2008). -

1 Population 2018 السكان

!_ اﻻحصاءات السكانية واﻻجتماعية FIRST SECTION POPULATION AND SOCIAL STATISTICS !+ الســكان CHAPTER I POPULATION السكان POPULATION يعتﺮ حجم السكان وتوزيعاته املختلفة وال يعكسها Population size and its distribution as reflected by age and sex structures and geographical الﺮكيب النوي والعمري والتوزيع الجغراي من أهم البيانات distribution, are essential data for the setting up of اﻻحصائية ال يعتمد علا ي التخطيط للتنمية .socio - economic development plans اﻻقتصادية واﻻجتماعية . يحتوى هذا الفصل عى بيانات تتعلق بحجم وتوزيع السكان This Chapter contains data related to size and distribution of population by age groups, sex as well حسب ا ل ن وع وفئات العمر بكل بلدية وكذلك الكثافة as population density per zone and municipality as السكانية لكل بلدية ومنطقة كما عكسا نتائج التعداد ,given by The Simplified Census of Population Housing & Establishments, April 2015. املبسط للسكان واملساكن واملنشآت، أبريل ٢٠١٥ The source of information presented in this chapter مصدر بيانات هذا الفصل التعداد املبسط للسكان is The Simplified Population, Housing & واملساكن واملنشآت، أبريل ٢٠١٥ مقارنة مع بيانات تعداد Establishments Census, April 2015 in comparison ٢٠١٠ with population census 2010 تقدير عدد السكان حسب النوع في منتصف اﻷعوام ١٩٨٦ - ٢٠١٨ POPULATION ESTIMATES BY GENDER AS OF Mid-Year (1986 - 2018) جدول رقم (٥) (TABLE (5 النوع Gender ذكور إناث المجموع Total Females Males السنوات Years ١٩٨٦* 247,852 121,227 369,079 *1986 ١٩٨٦ 250,328 123,067 373,395 1986 ١٩٨٧ 256,844 127,006 383,850 1987 ١٩٨٨ 263,958 131,251 395,209 1988 ١٩٨٩ 271,685 135,886 407,571 1989 ١٩٩٠ 279,800 -

Draft Press Release

NEWS ANADARKO BRINGS NEW OFFSHORE QATAR FACILITY ONLINE HOUSTON, May 6, 2003 - Anadarko Petroleum Corporation (NYSE: APC) announced today the installation and commissioning of a new permanent production facility at Al Rayyan oil field, offshore Qatar. Anadarko* is the operator of this field with a 92.5 percent interest in an exploration/production sharing agreement with the Government of Qatar. The Al Morjan platform was constructed in Dubai and Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates by Maritime Industrial Services Co. Ltd. The construction took 15 months and included the refurbishment of a 6-leg jack-up rig, fabrication and installation of new topsides, processing facilities and living quarters for 50 personnel. “Less than just one year since our entry in the Middle East as an operator, we’re pleased to have completed what is believed to be the largest jack-up permanent production facility ever built in the Gulf region,” said Bill Sullivan, Anadarko Executive Vice President, Exploration and Production. “We plan to expand our presence in the area and are currently exploring high potential acreage in south Al Rayyan, and in two other offshore blocks in Qatar.” On March 12, the completed platform was towed to the Al Rayyan field and installed at its new location in Block 12. The new platform has the capacity to process up to 45,000 barrels of oil per day and will allow Anadarko to significantly increase production from Al Rayyan field. The company is planning to drill exploration and development wells in the block later this year, pending approval by Qatar Petroleum. -

Qatar University College of Engineering

QATAR UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING INVESTIGATING ADAPTABILITY OF STADIUM PRECINCTS POST QATAR 2022 WORLD CUP: TOWARD AN ADAPTIVE STRATEGY THROUGH PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP (PPP) BY AMNA ALI AL-JEHANI A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of College of Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Urban Planning and Design June 2016 © 2016 Amna Al-jehani. All Rights Reserved. COMMITTEE PAGE The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Amna Ali Al-jehani defended on 13-June-2016. Dr. Fodil Fadli Committee Member Professor Attilio Petruccioli Committee Member Approved: ______________________________________________________ Dr. Khalifa Alkhalifa, Dean, College of Engineering II ABSTRACT Mega Sporting Events have become a way of transforming cities around the world. However, the sustainability of these large-scale transformations is questioned. This thesis aims to investigate the adaptability of stadium precincts post-Qatar 2022 World Cup based on selected case studies from Al Rayyan municipality. The challenges of using large facilities such as iconic stadiums are worth investigating. The thesis aims to find answers to the following questions: To what extent is Qatar 2022 World Cup stadiums is adaptive to its precincts? What impacts the adaptability of Qatar 2022 World Cup stadiums? And How an adaptive strategy through public-private partnership can take place for Post 2022 World Cup? A selection of case studies from Qatar includes Khalifa International Stadium, Qatar Foundation and Al Rayyan Stadiums are examined to answer the research questions. The thesis is based on qualitative case study research with three data collection and analysis tools. The tools used are site assessment (observations), expert interviews, and secondary data that include feedback from Al Rayyan residents toward Al Rayyan stadiums and precincts. -

We're Still Good to Fight for a Place in Top Four, Says Al Arabi's Lasogga

14 Tuesday, July 14, 2020 Sports Argentina star Mascherano to feature on @GA4Good Instagram Live SC.QA Mascherano is the lat- who, in addition to being spoke about gender equality, DOHA est star to appear on @GA- a dominant player for club as well as her experiences in 4good since the programme and country, has done some football, on @GA4good. ARGENTINA football star launched its online series. tremendous and admirable Hoogendijk detailed her Javier Mascherano will be Previous guests were Xavi charitable work with NGOs dream and determination as the special guest on Thurs- Hernández, Samuel off the pitch as well. a youngster to play for Ajax day’s @GA4Good Instagram “This kind of commit- – despite the lack of a wom- Live at 9pm Doha time (GMT ment to the community is a en’s team at the time. +3). The current Estudiant- crucial part of what Genera- She said: “Because of my es player will talk about the tion Amazing does and I am dream, I trained so hard and discipline and drive which sure that both our youth par- in 2012 Ajax started a wom- has helped him win a host ticipants and general audi- en’s team, so I was the first of major honours during his ences can take so much from one who signed for Ajax!” glittering football career. his incredible experience. Generation Amazing After making his name We are thrilled about host- will also continue its col- in the English Premier ing him this week to explore laboration with the Qatar League with West Ham these topics and more.” Children’s Museum on @ United and Liverpool, Al Khori added: “It will GA4Good, providing young Mascherano joined Spanish also be interesting for youth audiences with sports- giants Barcelona, where he to hear about the important themed arts and crafts ses- won five La Liga champion- work that Pierre van Hooi- sions and live physical activ- ships and two UEFA Cham- jdonk has been doing as a ities throughout the summer pions League titles. -

Medical Policy Agreement

SECTION C: QLM QATAR PREFERRED PROVIDER NETWORK – EMERALD PLUS You can choose from the listed provider which can meet with your members’ requirements within the area of cover of your selected plan: CONTACT DETAILS PROVIDER NAME TELEPHONE No. FAX No. PROVIDER TYPE ADDRESS HOSPITALS AL AHLI HOSPITAL 44898000 44898989 In-Outpatient Bin Omran Street Hilal West Area near The Mall R/A, In-Outpatient AL EMADI HOSPITAL 44666009 44678340 along D Ring Road AL MAGHRABI EYE, ENT & D Ring Road near Safeer Center Opp to In-Outpatient DENTAL CENTER 44238888 44646377 Hassan Al-Abdulla Dental Center C Ring Road near Andaloos Petrol In-Outpatient AMERICAN HOSPITAL 44421999 44424888 Station, Muntazah DOHA CLINIC HOSPITAL 44384333 44384395 In-Outpatient New Mirqab Street, Al Fareej Al Nasr Opposite to American Hospital, C Ring In-Outpatient TURKISH HOSPITAL 44992444 Road, New Salata ASTER HOSPITAL 44440499 In-Outpatient D Ring Road, behind Family Food Center HAMAD HOSPITAL & PRIMARY HEALTH CARE CENTERS On Re-imbursement Basis with (NO) co-insurance Doha POLYCLINICS AL-SAFA POLYCLINIC 44322448 44360572 Outpatient # 39 Al-Kinana St., Al-Nasr AL JAZEERA MEDICAL CENTRE 44351155 44351128 Outpatient Al Jaidah Building, Gulf Street AL JAZEERA MEDICAL CENTRE - MUAITHER BRANCH 44886464 44886363 Outpatient Building No. 312, Furousiya Street AL JAZEERA MEDICAL CENTRE - Building No. 24, Al Seliya Street, BUSIDRA BRANCH 44446062 Outpatient Maither South AL JAZEERA MEDICAL CENTRE - WAKRAH BRANCH 44446030 44140051 Outpatient Building No. 1890, Al Wakrah Road AL MANSOUR