THE FRENCH CONNECTION Wednesday 10 July 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simon Over Music Director and Principal Conductor

SIMON OVER MUSIC DIRECTOR AND PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR Simon Over studied at the Amsterdam Conservatoire, the Royal Academy of Music and Oxford University. From 1992 to 2002, Simon was a member of the music staff of Westminster Abbey, and Director of Music at both St Margaret’s Church and the Chapel of St Mary Undercroft in the Palace of Westminster. Since 2015 he has been Music Director at St Clement Danes, the central church of the Royal Air Force. He is the Founder-Conductor of the UK Parliament Choir and has conducted all the choir’s performances in conjunction with the City of London Sinfonia, La Serenissima, London Festival Orchestra and Southbank Sinfonia. Simon is Music Director and Principal Conductor of Southbank Sinfonia. He founded the orchestra in 2002 and has conducted many of its concerts throughout the UK, in Europe and in Asia. He has conducted Southbank Sinfonia in recordings with cellist Raphael Wallfisch, tenor Andrew Kennedy, pianist Alessio Bax, soprano Ilona Domnich and tenor Leo Nucci. In 2009-10 he conducted the orchestra in 71 performances of Every Good Boy Deserves Favour (Tom Stoppard/André Previn) at the National Theatre. In 2006, Simon was appointed Conductor of the Malcolm Sargent Festival Choir and has been associated with the Samling Foundation - working with young professional singers - since its inception. As Music Director of Bury Court Opera he conducted Dido and Aeneas, Rigoletto, La Cenerentola, Eugene Onegin, The Fairy Queen, The Rake’s Progress and Madama Butterfly. Further credits include Guest Conductor of the City Chamber Orchestra (Hong Kong), the Goyang Philharmonic Orchestra (Korea) and directing Mozart’s Bastien und Bastienne for the 2011 Vestfold International Festival in Norway. -

5024453-91Bc56-635212052525.Pdf

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Ludwig van Beethoven Major, Op. 73; the String Quartet in E-flat Major, PIANO CONCERTO NO. 5 Born Bonn, baptized December 17, 1770; died Op. 74 (Harp); the Piano Sonatas in F-sharp, & WORKS FOR SOLO PIANO March 26, 1827, Vienna G, and E-flat, Opp. 78, 79, and 81a; et al. Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-Flat Major, Op. 73 Unlike the Eroica Symphony (composed in Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-Flat Major, Op. 73 “Emperor” “Emperor” (1809) 1803, and in whose genesis Napoleon is 1 I. Allegro [20.26] In May 1809, Vienna fell to Napoleon for the directly, infamously, implicated), the Fifth Piano 2 II. Adagio un poco moto [6.55] second time in four years. The first conquest Concerto’s sobriquet – Emperor – was not 3 III. Rondo [10.13] of the Austrian capital, in 1805, happened bestowed by Beethoven, but by a publisher 4 Praeludium, WoO 55 [2.29] relatively quietly, as French forces entered the post facto. Although Beethoven completed Piano Sonata No. 27, Op. 90 city without opposition. But the 1809 siege the Concerto before the French invasion, the 5 I. Mit Lebhaftigkeit und durchaus mit Empfindung und Ausdruck [5.26] of Vienna was accompanied by a heavy zeitgeist surrounding the Napoleonic Wars 6 II. Nicht zu geschwind und sehr singbar vorgetragen [6.27] bombardment. History has remembered the seems nevertheless to have permeated the image of Beethoven cowering in his brother’s work. Witness its martial rhythms and Contredanses, WoO 14 7 I. Contredanse in C Major [0.29] basement, holding a pillow tightly around his suggestions of military triumph in the 8 II. -

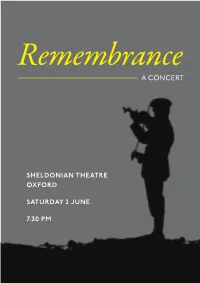

Remembrance a CONCERT

Remembrance A CONCERT SHELDONIAN THEATRE OXFORD SATURDAY 2 JUNE 7.30 PM I. POST-WAR: COMMEMORATION, RECONSTRUCTION, RECONCILIATION Tonight’s concert is the culmination of Post-War: Commemoration, Reconstruction, Reconciliation, a Mellon-Sawyer Seminar Series which has been running at the Univer- sity of Oxford and Oxford Brookes University in 2017–18. It has brought together academics from many different fields, politicians, people who have played a role in peace negotiations and leading figures from cultural policy and the charitable sector. They have been joined by novelists, poets, artists and musicians whose work has marked war in some way. Featured speakers have included author Aminatta Forna, architect Daniel Libeskind and composer Jonathan Dove. The Series has been divided into three strands: Textual Commemoration (Octob er– December 2017), Monumental Commemoration (January–March 2018) and Aural Commemoration (April–June 2018). Each strand was launched by an event featuring an internationally-renowned figure from the arts. These launch events were followed by two panel -led workshops each term. There have also been three events aimed directly at post-graduates: a training day in object-based research methods, a postgraduate forum and a one-day conference. Tonight’s Concert and the Series as a whole have been funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in memory of John E. Sawyer. Thanks, too, to Villa Maria for its support. The Launch of the Textual Strand: Award- Winning Novelist Aminatta Forna, OBE in Conversation with Professor Elleke Boehmer. Image credit: John Cairns Photography. PROGRAMME SIMON OVER | conductor ANNABEL DRUMMOND | violin ANNA LEESE | soprano JON STAINSBY | baritone TESSA PETERSEN | guest concertmaster CITY CHOIR DUNEDIN (NEW ZEALAND) THE PARLIAMENT CHOIR SOUTHBANK SINFONIA VAUGHAN WILLIAMS | The Lark Ascending AUGUSTA HOLMÈS | La Nuit et l’Amour RAVEL | Le Tombeau de Couperin INTERVAL (20 minutes) ANTHONY RITCHIE | Gallipoli to the Somme (European première) 1. -

Download Booklet

Alessio Bax Plays Mozart ARTIST’S NOTE Mozart did not write specific cadenzas for K. 491, but many major composers and pianists have Mozart’s piano concerti were the reason I fell in done so, usually expanding upon the darkness, love with the piano. I vividly remember hearing grandeur and virtuosity of the piece. While Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K. 491 the development section of the first movement of cadenzas are an opportunity to showcase a 1 I. Allegro [13.19] K. 467 during the closing titles of a TV mini-series performer’s keyboard skills, in the case of K. 491 2 II. Larghetto [7.16] on the development of the atomic bomb and how I prefer not to interfere and disrupt the order 3 III. Allegretto [8.50] it led to the closing events of World War Two. It Mozart so carefully shapes in the first movement. Piano Concerto No. 27 in B-flat major, K. 595 was heavy subject matter for an eight-year old, I have written a small cadenza based simply on 4 I. Allegro [14.08] but what blew me away was the power of that the material Mozart provides, which, in my 5 II. Larghetto [8.40] music. I instantly decided to learn it, and even humble opinion, keeps the continuity of the 6 III. Allegro [8.53] made a little version for piano trio to perform pacing of the movement while shifting the focus with my violinist brother and a cellist friend. For from the orchestra to the soloist. -

WFMT Dear Member, Renée Crown Public Media Center 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Sesame Street Premiered on WTTW at 9:00 Am on November 10, 1969

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT Dear Member, Renée Crown Public Media Center 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Sesame Street premiered on WTTW at 9:00 am on November 10, 1969. 50 years and Chicago, Illinois 60625 counting, we are celebrating this colorful community of monsters, birds, grouches, and humans all year long – beginning with an all-day outdoor festival featuring a Main Switchboard character stage show, activities, meet and greets, and more. You’ll find details inside. (773) 583-5000 Member and Viewer Services Also, look out for special content on television, and our social and digital platforms. (773) 509-1111 x 6 WTTW will celebrate LGBT Pride Month with relevant content including a new Websites American Masters profile of playwright Terrence McNally, and two documentaries – wttw.com The Lavender Scare, a history of the gay community’s fight for civil rights, and POV: wfmt.com The Gospel of Eureka, about an Arkansas town building bridges between religious faith and sexual orientation. On wttw.com, uncover Chicago’s LGBT history; mark the Publisher Anne Gleason centennial of the Treaty of Versailles and the 75th anniversary of D-Day; and recap Art Director the new season of Endeavour. Tom Peth WTTW Contributors Julia Maish WFMT will be out and about all summer long. Come see us at the Grant Park Music Dan Soles Festival in June featuring concerts with violinists Benjamin Beilman and Augustin WFMT Contributors Andrea Lamoreaux Hadelich and pianist Inon Barnatan. We’ll take you behind the scenes at Pritzker David Polk Pavilion with music, interviews, and more on wfmt.com and Facebook Live. -

Rodion Shchedrin 12 Ni 5816 Ni 5816

NI 5816 SERGE PROKOFIEV Cinq Mélodies • Parabola Concertante Concertino • Classical Symphony Raphael Wallfisch, cello Southbank Sinfonia Simon Over Photo by: Elizabeth Hughes Southbank Sinfonia is indebted to the following trusts and individuals who helped to fund this recording: The Dunard Fund • The Robert Gavron Charitable Trust Don and Sue Guiney • Dolf Mootham The Serge Prokofiev Foundation • Joe Ryan RODION SHCHEDRIN 12 NI 5816 NI 5816 SERGE PROKOFIEV & RODION SHCHEDRIN Violin I Viola Oboe Raphael Wallfisch, cello Susie Watson Audrey Barr Bethany Akers Southbank Sinfonia Anna Banaszkiewicz Neil Valentine Rosalie Philips Natalie Dudman Amy Fawcett Clarinet Simon Over, conductor Raja Halder Beverley Parry Thomas Lessels Serge Prokofiev Skye McIntosh Linda Kidwell Luisa Rosina Cinq Mélodies Op.35 (1920) 15.20 Sarah Colman Cello 1 Transcribed for cello & orchestra by Rodion Shchedrin (nos. 1,3,4 & 5) & Serge Prokofiev (no.2) Paloma Deike Bassoon Steffan Rees 2 I Andante 2.39 Rustom Pomeroy Neil Strachan Edward Furse 3 II Lento, ma non troppo 3.10 Rob Simmons Fiona Troon Jamie Pringle 4 III Animato, ma non troppo 4.05 Alice Rickards 5 IV Andantino, ma poco scherzando 1.33 Verity Harding Horn V Andante non troppo 3.53 Violin II Patrick Broderick Double bass Rodion Shchedrin Joe Ichinose Miriam Holmes 6 Jacqueline Dossor Parabola Concertante for cello, strings & timpani (2001) 16.27 April Johnson Nicholas Wolstencroft Lowri Morgan Michael Allen, timpani soloist Erika Eisele Andy Marshall Trumpet Serge Prokofiev Leah Johnston Gordon Richerby 7 Concertino Op.132 (orch. Vladimir Blok) 19.43 Leire Fernandez Harp Emma Pritchard 8 I Andante mosso 8.43 Stelios Chatziiosifidis Celine Saout 9 II Andante 6.01 Gillian Ripley Percussion Allegretto Flute III 4.59 Laurine Rochut Michael Allen Gareth Hanson 0 Classical Symphony Op.25 (1926) 14.32 Amelia Jacobs Marlene Verwey q I Allegro 4.16 w II Larghetto 4.05 e III Gavotta. -

Simon Over Music Director and Principal Conductor

SIMON OVER MUSIC DIRECTOR AND PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR Simon Over studied at the Amsterdam Conservatoire, the Royal Academy of Music and Oxford University. From 1992 to 2002, Simon was a member of the music staff of Westminster Abbey, and Director of Music at both St Margaret’s Church and the Chapel of St Mary Undercroft in the Palace of Westminster. Since 2015 he has been Music Director at St Clement Danes, the central church of the Royal Air Force. He is the Founder-Conductor of the UK Parliament Choir and has conducted all the choir’s performances in conjunction with the City of London Sinfonia, La Serenissima, London Festival Orchestra and Southbank Sinfonia. Simon is Music Director and Principal Conductor of Southbank Sinfonia. He founded the orchestra in 2002 and has conducted many of its concerts throughout the UK, in Europe and in Asia. He has conducted Southbank Sinfonia in recordings with cellist Raphael Wallfisch, tenor Andrew Kennedy, pianist Alessio Bax, soprano Ilona Domnich and tenor Leo Nucci. In 2009-10 he conducted the orchestra in 71 performances of Every Good Boy Deserves Favour (Tom Stoppard/André Previn) at the National Theatre. In 2006, Simon was appointed Conductor of the Malcolm Sargent Festival Choir and has been associated with the Samling Foundation - working with young professional singers - since its inception. As Music Director of Bury Court Opera he conducted Dido and Aeneas, Rigoletto, La Cenerentola, Eugene Onegin, The Fairy Queen, The Rake’s Progress and Madama Butterfly. Further credits include Guest Conductor of the City Chamber Orchestra (Hong Kong), the Goyang Philharmonic Orchestra (Korea) and directing Mozart’s Bastien und Bastienne for the 2011 Vestfold International Festival in Norway. -

Musicians Look After the Music - We Look After Musicians Wednesday 20 November 2013

Notes | Issue 10 | Summer Edition 2013 Notes Musicians look after the music - we look after musicians Wednesday 20 November 2013 Service ~ Westminster Abbey ~ 11am The service will include the premiere of Robin Holloway’s new anthem, On a Drop of Dew, sung by the combined choirs of Westminster Abbey, St Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Cathedral Readers: Dame Janet Baker and Ian Bostridge Lunch ~ Banqueting House ~ 1pm Booking opens mid-September Foreword A message from our Chief Executive Contents Over the last few years we have been updating how we work, aiming to be more responsive 3 Foreword to musicians and acting as quickly as possible 4 – 5 An evening with when help is needed. We’ve been thinking internationally acclaimed about those professional musicians who don’t soprano, Susan Bullock know about us. We have also been thinking about how we might actively link with a 6 – 7 When disaster strikes… profession and industry that is unrecognisable Daniel Mullin’s story to how it was even ten years ago. To this end we have developed an ambitious plan, 8 Lauretta Boston’s Story Time to Evolve. The first task highlighted in 9 Tim Priestley’s legacy – the plan is to change our name to Help a new website for Musicians UK in a bid to be more direct about what we do and who we aim to help. songwriters and This decision was included in the plan after lots of soul-searching and consultation. tunesmiths Our beloved name, Musicians Benevolent Fund, won’t be jettisoned completely. Like many other charities we’ll maintain it in the background. -

Southbank Sinfonia at St John's Smith Square

Summer in the Square Southbank Sinfonia at St John’s Smith Square www.southbanksinfonia.co.uk www.sjss.org.uk Fri 23 Jul Sat 24 Jul Sun 25 Jul Principal Partner Summer in the Square 23 | 24 | 25Supporters July 2021 Welcome to St John’s Smith Square for the inaugural Summer in the Square festival. We’re thrilled to have you with us at the new home of Southbank Sinfonia and hope you thoroughly enjoy the music and summer atmosphere, as well as the odd glass of wine! Next year will be the twentieth anniversary of The festival usually welcomes distinguished guest Southbank Sinfonia and also of the Anghiari Festi- performers and also offers concerto opportunities val where - in normal times - the orchestra is resi- to current members of the orchestra with our col- dent in a small Italian village for a week of intense leagues David Corkhill and Eugene Lee directing music making, punctuated with pizzas and Pro- concerts. All of those features are to be enjoyed secco in a very sociable atmosphere. this weekend with our dear friend Ruth Rogers opening the festival playing Beethoven’s Violin Shared by a few hundred supporters, visiting for Concerto in an all-Beethoven concert, compensat- their annual fix of glorious music in a beautiful set- ing for the pandemic denying his due celebration ting, the festival is an opportunity for players and last year; and our long-term collaborator, pianist supporters to get to know each other, both from Tom Poster brings events to a celebratory close the stage, which is placed in the middle of a piaz- with the jazz-infused Piano Concerto by Ravel.