Final Report to the Full Legislative Commission on Minnesota Resources in Early February 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Chapter 85

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 85.011 CHAPTER 85 DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION STATE PARKS, RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES 85.06 SCHOOLHOUSES IN CERTAIN STATE PARKS. 85.011 CONFIRMATION OF CREATION AND 85.20 VIOLATIONS OF RULES; LITTERING; PENALTIES. ESTABLISHMENT OF STATE PARKS, STATE 85.205 RECEPTACLES FOR RECYCLING. RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES. 85.21 STATE OPERATION OF PARK, MONUMENT, 85.0115 NOTICE OF ADDITIONS AND DELETIONS. RECREATION AREA AND WAYSIDE FACILITIES; 85.012 STATE PARKS. LICENSE NOT REQUIRED. 85.013 STATE RECREATION AREAS AND WAYSIDES. 85.22 STATE PARKS WORKING CAPITAL ACCOUNT. 85.014 PRIOR LAWS NOT ALTERED; REVISOR'S DUTIES. 85.23 COOPERATIVE LEASES OF AGRICULTURAL 85.0145 ACQUIRING LAND FOR FACILITIES. LANDS. 85.0146 CUYUNA COUNTRY STATE RECREATION AREA; 85.32 STATE WATER TRAILS. CITIZENS ADVISORY COUNCIL. 85.33 ST. CROIX WILD RIVER AREA; LIMITATIONS ON STATE TRAILS POWER BOATING. 85.015 STATE TRAILS. 85.34 FORT SNELLING LEASE. 85.0155 LAKE SUPERIOR WATER TRAIL. TRAIL PASSES 85.0156 MISSISSIPPI WHITEWATER TRAIL. 85.40 DEFINITIONS. 85.016 BICYCLE TRAIL PROGRAM. 85.41 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI PASSES. 85.017 TRAIL REGISTRY. 85.42 USER FEE; VALIDITY. 85.018 TRAIL USE; VEHICLES REGULATED, RESTRICTED. 85.43 DISPOSITION OF RECEIPTS; PURPOSE. ADMINISTRATION 85.44 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI TRAIL GRANT-IN-AID 85.019 LOCAL RECREATION GRANTS. PROGRAM. 85.021 ACQUIRING LAND; MINNESOTA VALLEY TRAIL. 85.45 PENALTIES. 85.04 ENFORCEMENT DIVISION EMPLOYEES. 85.46 HORSE -

The Campground Host Volunteer Program

CAMPGROUND HOST PROGRAM THE CAMPGROUND HOST VOLUNTEER PROGRAM MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 1 CAMPGROUND HOST PROGRAM DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION Introduction This packet is designed to give you the information necessary to apply for a campground host position. Applications will be accepted all year but must be received at least 30 days in advance of the time you wish to serve as a host. Please send completed applications to the park manager for the park or forest campground in which you are interested. Addresses are listed at the back of this brochure. General questions and inquiries may be directed to: Campground Host Coordinator DNR-Parks and Recreation 500 Lafayette Road St. Paul, MN 55155-4039 651-259-5607 [email protected] Principal Duties and Responsibilities During the period from May to October, the volunteer serves as a "live in" host at a state park or state forest campground for at least a four-week period. The primary responsibility is to assist campers by answering questions and explaining campground rules in a cheerful and helpful manner. Campground Host volunteers should be familiar with state park and forest campground rules and should become familiar with local points of interest and the location where local services can be obtained. Volunteers perform light maintenance work around the campground such as litter pickup, sweeping, stocking supplies in toilet buildings and making emergency minor repairs when possible. Campground Host volunteers may be requested to assist in the naturalist program by posting and distributing schedules, publicizing programs or helping with programs. Volunteers will set an example by being model campers, practicing good housekeeping at all times in and around the host site, and by observing all rules. -

Minnesota State Parks.Pdf

Table of Contents 1. Afton State Park 4 2. Banning State Park 6 3. Bear Head Lake State Park 8 4. Beaver Creek Valley State Park 10 5. Big Bog State Park 12 6. Big Stone Lake State Park 14 7. Blue Mounds State Park 16 8. Buffalo River State Park 18 9. Camden State Park 20 10. Carley State Park 22 11. Cascade River State Park 24 12. Charles A. Lindbergh State Park 26 13. Crow Wing State Park 28 14. Cuyuna Country State Park 30 15. Father Hennepin State Park 32 16. Flandrau State Park 34 17. Forestville/Mystery Cave State Park 36 18. Fort Ridgely State Park 38 19. Fort Snelling State Park 40 20. Franz Jevne State Park 42 21. Frontenac State Park 44 22. George H. Crosby Manitou State Park 46 23. Glacial Lakes State Park 48 24. Glendalough State Park 50 25. Gooseberry Falls State Park 52 26. Grand Portage State Park 54 27. Great River Bluffs State Park 56 28. Hayes Lake State Park 58 29. Hill Annex Mine State Park 60 30. Interstate State Park 62 31. Itasca State Park 64 32. Jay Cooke State Park 66 33. John A. Latsch State Park 68 34. Judge C.R. Magney State Park 70 1 35. Kilen Woods State Park 72 36. Lac qui Parle State Park 74 37. Lake Bemidji State Park 76 38. Lake Bronson State Park 78 39. Lake Carlos State Park 80 40. Lake Louise State Park 82 41. Lake Maria State Park 84 42. Lake Shetek State Park 86 43. -

Campground Host Program

Campground Host Program MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF PARKS AND TRAILS Updated November 2010 Campground Host Program Introduction This packet is designed to give you the information necessary to apply for a campground host position. Applications will be accepted all year but must be received at least 30 days in advance of the time you wish to serve as a host. Please send completed applications to the park manager for the park or forest campground in which you are interested. You may email your completed application to [email protected] who will forward it to your first choice park. General questions and inquiries may be directed to: Campground Host Coordinator DNR-Parks and Trails 500 Lafayette Road St. Paul, MN 55155-4039 Email: [email protected] 651-259-5607 Principal Duties and Responsibilities During the period from May to October, the volunteer serves as a "live in" host at a state park or state forest campground for at least a four-week period. The primary responsibility is to assist campers by answering questions and explaining campground rules in a cheerful and helpful manner. Campground Host volunteers should be familiar with state park and forest campground rules and should become familiar with local points of interest and the location where local services can be obtained. Volunteers perform light maintenance work around the campground such as litter pickup, sweeping, stocking supplies in toilet buildings and making emergency minor repairs when possible. Campground Host volunteers may be requested to assist in the naturalist program by posting and distributing schedules, publicizing programs or helping with programs. -

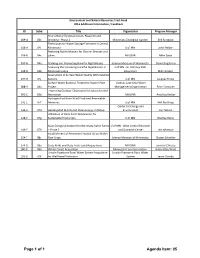

Of 1 Agenda Item: 05 ENRTF ID: 009-A / Subd

Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund 2016 Additional Information / Feedback ID Subd. Title Organization Program Manager Prairie Butterfly Conservation, Research and 009‐A 03c Breeding ‐ Phase 2 Minnesota Zoological Garden Erik Runquist Techniques for Water Storage Estimates in Central 018‐A 04i Minnesota U of MN John Neiber Restoring Native Mussels for Cleaner Streams and 036‐B 04c Lakes MN DNR Mike Davis 037‐B 04a Tracking and Preventing Harmful Algal Blooms Science Museum of Minnesota Daniel Engstrom Assessing the Increasing Harmful Algal Blooms in U of MN ‐ St. Anthony Falls 038‐B 04b Minnesota Lakes Laboratory Miki Hondzo Assessment of Surface Water Quality With Satellite 047‐B 04j Sensors U of MN Jacques Finlay Surface Water Bacterial Treatment System Pilot Vadnais Lake Area Water 088‐B 04u Project Management Organization Brian Corcoran Improving Outdoor Classrooms for Education and 091‐C 05b Recreation MN DNR Amy Kay Kerber Hydrogen Fuel from Wind Produced Renewable 141‐E 07f Ammonia U of MN Will Northrop Center for Energy and 144‐E 07d Geotargeted Distributed Clean Energy Initiative Environment Carl Nelson Utilization of Dairy Farm Wastewater for 148‐E 07g Sustainable Production U of MN Bradley Heins Solar Energy Utilization for Minnesota Swine Farms U of MN ‐ West Central Research 149‐E 07h – Phase 2 and Outreach Center Lee Johnston Establishment of Permanent Habitat Strips Within 154‐F 08c Row Crops Science Museum of Minnesota Shawn Schottler 174‐G 09a State Parks and State Trails Land Acquisitions MN DNR Jennifer Christie 180‐G 09e Wilder Forest Acquisition Minnesota Food Association Hilary Otey Wold Lincoln Pipestone Rural Water System Acquisition Lincoln Pipestone Rural Water 181‐G 09f for Well Head Protection System Jason Overby Page 1 of 1 Agenda Item: 05 ENRTF ID: 009-A / Subd. -

People Saving Special Places

People Saving Special Places Parks & Trails Council of Minnesota Annual Report 2006 Dear Friends innesotans treasure our parks and trails because they give us Maccess to the state’s most outstanding natural, cultural and scenic resources. They are special places where we recreate, interact with nature and enjoy peaceful solitude. Since 1954, the Parks & Trails Council has protected, enhanced and expanded these great outdoor places for generations upon generations of people to enjoy. On the pages of this annual report you will find evidence that the Parks & Trails Council continues to excel in fulfilling our mission. You will also find examples of how we have helped make Minnesota’s park and trail systems the envy of the nation. Clearly, we could not do the important work we do without the generous support of our members and donors, and for that we thank each and every one of you who has made contributions to our wonderful organization. Always determined and forward thinking, the Parks & Trails Council headed into the 2006 legislative session armed with a comprehensive agenda that helped secure nearly $25 million for state park and trail acquisition, development and rehabilitation. The impact of these investments can be felt in nearly every corner of the state. Grant Merritt Our efforts at the Capitol were successful because of the strong bonds we’ve formed with more than 100 grassroots citizen groups around the state. We continued to cultivate these partnerships in 2006 by hosting events such as our biennial conference, our annual Day on the Hill and the first-ever North Shore Parks and Trails Leadership Summit with workshops designed to both energize and educate parks and trails advocates about the important issues of the day. -

2015 Annual Report

Boulders saved at Banning State Park along the Kettle River 2015 Annual Report 1 Willard Munger State Trail ~ near the connection into Jay Cooke State Our Mission To acquire, protect and enhance critical land for the public’s use and benefit. Our Vision We envision an interconnected system of parks, trails, waterways, natural areas and open spaces that provide all Minnesotans with outstanding outdoor recreational opportunities and that preserve the natural diversity of our state. Cover photos left to right from top: Kettle River in Banning State Park; Advocates for the Shooting Star State Trail at our 2015 Day on the Hill; Reuel Harmon Award at our 2015 Annual Dinner; Riders from our 2015 Bike Minnesota event at Inspiration Peak State Wayside and along the Central Lakes State Trail; Magney Circle members at the proposed Minnesota Valley State Trail. 2 Michael Tegeder, President Brett Feldman, Executive Director Banning State Park ~ wolf creek (photo by Gary Alan Nelson) Dear Friends Working together to achieve our mission Putting the finishing touches on our Annual Report before it goes to press is always a fun time of year. It's an opportunity to bundle up our efforts and accomplishments into a tidy package that we can reflect upon. It's like a time capsule that years from now we can look back on to see how far we've come. In fact, we recently dusted off our annual report from 20 years ago for this very reason. At that time we were celebrating a boost in membership to 880 members. Today those numbers have increased four-fold to 3,700 members and our budget tells the same story. -

Downloadable Conference Schedule

Our Cultural Legacy: Current Research, Methods and Reports Council for Minnesota Archaeology 2013 Conference February 8th and 9th Inver Hills Community College Inver Grove Heights, Minnesota Program and Abstracts Sponsored by: Council for Minnesota Archaeology Minnesota Archaeological Society Archaeology Department of the Minnesota Historical Society Inver Hills Community College Anthropology Department Inver Hills Community College Anthropology Club Minnesota Office of the State Archaeologist Symposium Committee: Patricia Emerson - Archaeology Department of the Minnesota Historical Society Jeremy L. Nienow - Inver Hills Community College Anthropology Department Bruce Koenen - Office of the State Archaeologist Pre-Conference Events: Thursday, February 7th Book Exchange and Lithic Collection Open House On the Thursday evening before the CMA Conference (February 7, 2013) from 6:00 to 7:30 pm the Office of the State Archaeologist (OSA) will host a book exchange at the Historic Fort Snelling Visitor Center. At the same time researchers involved with the Minnesota Historical Society lithic comparative collection will host an open house also at the Historic Fort Snelling Visitor Center showcasing recent developments with the lithic comparative collection. The OSA has accumulated a number of duplicate reports, textbooks and periodicals which will be available free to researchers beginning at 6 pm. Subject matter ranges from Minnesota archaeology through all of the subfields of anthropology. Archaeologists and researchers attending the conference are invited to bring books to share, with the caveat that you are responsible for taking home your own books if no one else takes them. The subject matter should also be of an anthropological or historical nature. If you have publications you would like to sell either bring a price list of your books, including your contact information to post, or contact the OSA and we will arrange some space for you (612-725-2729). -

State Park Management O

REPORT # 00-02 OFFICE OF THE LEGISLATIVE AUDITOR OO LL AA STATE OF MINNESOTA PROGRAM EVALUATION REPORT State Park Management Photo courtesy of Minnesota Department of Natural Resources JANUARY 2000 Photo Credits: Page Source Description Cover Department of Natural Resources Headwaters of the Mississippi at Itasca State Park 10 Department of Natural Resources Campers at Wild River State Park 22 Office of the Legislative Auditor Nature Store at Fort Snelling State Park 29 Department of Natural Resources Skiers at Wild River State Park 47 Department of Natural Resources Interpretive sign at Maplewood State Park 52 Department of Natural Resources Prescribed burn at Itasca State Park 55 Department of Natural Resources Park officer on bicycle 70 Office of the Legislative Auditor Black-topped trail at Father Hennepin State Park 74 Office of the Legislative Auditor Observation deck at Hayes Lake State Park 76 Office of the Legislative Auditor Contact station at Bear Head Lake State Park 78 Office of the Legislative Auditor Low-water crossing in Beaver Creek Valley State Park 91 Department of Natural Resources Camping at Interstate State Park Evaluation Report Summary: PE00-02 OFFICE OF THE LEGISLATIVE AUDITOR OOLL AA STATE OF MINNESOTA State Park Management January 26, 2000 Major Findings: • DNR has a well-defined process for identifying capital improvement projects in state parks. The state park • Overall, the Parks and Recreation 2000-2001 operating budget was Division of the Department of Natural increased to fund the operating costs Resources (DNR) manages of new buildings funded in the 1998 Minnesota’s state parks reasonably state bonding bill. -

Senator ...Moves to Amend SF No

05/09/18 01:42 PM COUNSEL SJJ/CM/RDR SCS4013A-1 1.1 Senator .................... moves to amend S.F. No. 4013 as follows: 1.2 Delete everything after the enacting clause and insert: 1.3 "ARTICLE 1 1.4 APPROPRIATIONS 1.5 Section 1. CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT APPROPRIATIONS. 1.6 The sums shown in the column under "Appropriations" are appropriated from the bond 1.7 proceeds fund, or another named fund, to the state agencies or officials indicated, to be 1.8 spent for public purposes. Appropriations of bond proceeds must be spent as authorized by 1.9 the Minnesota Constitution, article XI, section 5, paragraph (a), to acquire and better public 1.10 land and buildings and other public improvements of a capital nature, or as authorized by 1.11 the Minnesota Constitution, article XI, section 5, paragraphs (b) to (j), or article XIV. Unless 1.12 otherwise specified, money appropriated in this act: 1.13 (1) may be used to pay state agency staff costs that are attributed directly to the capital 1.14 program or project in accordance with accounting policies adopted by the commissioner of 1.15 management and budget; 1.16 (2) is available until the project is completed or abandoned subject to Minnesota Statutes, 1.17 section 16A.642; and 1.18 (3) for activities under Minnesota Statutes, sections 16B.307, 84.946, and 135A.046, 1.19 should not be used for projects that can be financed within a reasonable time frame under 1.20 Minnesota Statutes, section 16B.322 or 16C.144. 1.21 Except for a grant subject to requirements of a statutory program, a grant under this act 1.22 to a political subdivision is subject to Minnesota Statutes, sections 16A.86 and 16A.502. -

Otter Tail County

Otter Tail Scattered Lands State Forest Road and Trail Designations H! Big Cormorant Meadow Nottage Stilke C Trieglaff H! Laura H! h Lake Eunice i Evergreen Katie Maud Cottage A lt 87 g c o North Menahga n in Rollag e o k c r Gebo c i n o Rollag n Melissa Lind Reeves t u k Menahga S E in Ida r B H! Dewey H! irit Cormorant Sp Collet Town Frazee Jim Cook (east) ll Jim Cook (west) Buck's MillH! PondMi H! Buck S a Bucks Mill u e e y r E Boot d Albertson Stein e 32 R Stony Creek Detention Burton Little Pelican Graham Fischer (Carroll) Cooks y nd h Holbrook a p H x r Pelican i Thomas u S e Gray M Fiv Homestead y ir Candor a r F e Price im r Schrams e W v l lp i a S c S Keyes Tansem Tee H! Yaeger Baker Gertrude Little Rose Harrison (Helgeson) Leek (Trowbridge) Butler BusingerSeim H! T a Barnesville m Bear R Solem a Rose Rankle im i Barnesville r Dunvilla J c a Hillview Bradbury e c H! TansemRanum 34 H! Vergas H! Mike E dn Little Long a Pete Hook Vergas Coffee Luce ) F H! 228 Whiskey n Delaney r o Little Rice i a H! t r n o k Lawrence p l i L Maple n ong (m h ain la t ke) r Sand o n ( ve e Gro i z z i L Otter n Little Pine oo Alfred t L Sands as Sybil West Spirit E H! Mink Schuster Becks Crystal Heart Sebeka Norwegian Grove McCollum (Tenter) Gaards Wendt rbs H! 227 East Spirit Ke Kemp Grunard Roman West Olaf Grand View Heights Prairie Dora Little Spirit Little McDonald H! East Olaf Moenkedick Kopperud Big Pine Ceynowa 94 Little Crow William Berend Jerry Bacon l Big Crow Walde u Nitche Deadman a e Rusch P McCollum c Perham Davies Warehouse -

Mission Statement

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp Mission Statement The n1ission ofthe State Archaeologist is to pron10te archaeological research, share archaeologicallaiowledge, andprotect archaeological resources for the benefit ofall ofthe people ofMinnesota. Dedication This alU1ual report is dedicated to my Inother, Patricia Roth Anfinson (1923 - 2012). She was a great inspiration, a source ofconstant support, and had a keen interest in all her children's lives both personal and professional. 1 Abstract In fiscal' year 2012, the Office ofthe State Archaeologist (OSA) was involved in a wide variety ofactivities in order to fulfill legal obligations, protect archaeological sites, and support the advancement ofMimlesota archaeology. Chapter 1 ofthe Annual Report provides a briefhistory ofthe GSA and lists the principal duties and responsibilities ofthe State Archaeologist. Chapter 2 sUlllinarizes GSA activities and other Minnesota archaeological activities in FY 2012 by program area. Major FY 2012 GSA accomplishments include: reviewing 321 site inventory fonns, reviewing 38 development projects, doing field research on 19 major MS 308.08 burial cases, and helping to direct the Statewide Survey ofHistorical andArchaeological Sites. Basic GSA Fiscal Year (FY) 2012 and Calendar Year (CY) 2012 statistics are: FY12 CY12 Licenses Approved: ·84 85 Site Forms Reviewed: 321 285 Site Numbers Assigned: 280 248 Reports Added: 114 127 Projects Reviewed: 38 77 Major Burial Cases: 19 Burial Authentications: 11 Chapter 3 provides an assessment ofthe current state ofMinnesota archaeology including a summary ofprojects funded by the Legacy Amendment Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund for the Statewide Survey ofHistorical andArchaeological Sites and a plan for GSA activities in FY 2013.