EFFECTUAL CALL OR CAUSAL EFFECT? SUMMONS, SOVEREIGNTY and SUPERVENIENT GRACE Kevin J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 8, 2020 WORSHIP: Psalm 149:1-4 *HYMN: Trinity (Blue) 57

THE LORD’S DAY A. They that are effectually called do in this life partake of justification, March 8, 2020 adoption, and sanctification, and the several benefits which in this life do PRELUDE either accompany or flow from them CONGREGATIONAL SCRIPTURE READING: Psalm 4, Trinity Hymnal p. 786 WELCOME AND ANNOUNCEMENTS (10:55 AM) ANTHEM: Look at the World INTROIT PRAYER OF INTERCESSION AND THE LORD’S PRAYER *CALL TO WORSHIP: Psalm 149:1-4 Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom *INVOCATION come. Thy will be done on earth, as it is in heaven. Give us this day our 9 *HYMN: Trinity (Blue) 57 - Hallelujah, Praise Jehovah, O My Soul daily bread. And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors. And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil: For thine is the kingdom, CONFESSION OF SIN and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen. Minister: O Lord our God, we acknowledge before Your holy majesty that we *PSALTER: Bible Songs (Green) 11 - God the Troubled Soul’s Refuge are poor sinners, conceived and born in guilt and in corruption, prone to do evil. All: We are unable on our own to do good. Because of our sin, we PRAYER FOR ILLUMINATION endlessly violate Your holy commandments. SERMON TEXT: Luke 23:39-43 (p. 884; LP p. 1050) Minister: But, Lord, with heartfelt sorrow we repent and turn away from all our offenses. We condemn ourselves and all our evil ways. SERMON: “Seven Last Words of Christ from the Cross – Salvation (2)” All: Have compassion on us, most gracious God, for the sake of Your son *HYMN: Trinity (Blue) 455 - And Can It Be That I Should Gain Jesus Christ our Lord. -

Salvation Series

What the Scriptures Say About Salvation Pastor Scott Estell What the Scriptures Say About Salvation Table of Contents Lesson 1 Introduction Lesson 2 Calling and Regeneration Lesson 3 Conversion: Repentance Lesson 4 Conversion: Faith Lesson 5 Justification Lesson 6 Sanctification: Explanation Lesson 7 Sanctification: Errors Lesson 8 Eternal Security Lesson 9 Perseverance Lesson 10 Assurance Lesson 11 Glorification Unless otherwise indicated, all Scriptural citations are from the New American Standard Bible (NASB). TM PDF Editor1 What the Scriptures Say About Salvation Pastor Scott Estell What the Scriptures Say About Salvation Resources Chapters 14-18 of Systematic Theology by Charles Hodge Redemption Accomplished and Applied by John Murray (1955) Chapters 28-34 of Lectures in Systematic Theology by Henry Thiessen (1979) Evangelical Dictionary of Theology , edited by Walter Elwell (1984) Chapters 42-48 of Christian Theology by Millard Erickson (1985) Chapters 48-58 of Basic Theology by Charles Ryrie (1986) Chapter 24 of The Moody Handbook of Theology by Paul Enns (1989) Saved by Grace by Anthony Hoekema (1989) Charts of Christian Theology & Doctrine by H. Wayne House (1992) Chapters 31-43 of Systematic Theology by Wayne Grudem (1994) How Can I be Sure I’m a Christian? by Donald Whitney (1994) The Cross and Salvation by Bruce Demarest (1997) Chapter 19 of A New Systematic Theology of the Christian Faith by Robert Reymond (1998) TM Chapters 37–48 of Volume 3 of A Systematic Theology of Biblical Christianity by Rolland McCune (2010) PDF Editor2 What the Scriptures Say About Salvation Pastor Scott Estell Lesson 1: Introduction The study of what the Scriptures say about salvation is called “soteriology,” from the Greek word for salvation, soteria . -

Systematic Theology

SYSTEMATIC THEOLOGY Vincent Cheung To Denise, my wife, best friend, companion for life, fellow-servant to the Lord Jesus Christ, and partner in the publication of his gospel, to her, I dedicate all my writings, with great love and affection, forever. Copyright © 2010 by Vincent Cheung http://www.vincentcheung.com Previous editions published in 2001 and 2003. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted without the prior permission of the author or publisher. Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are taken from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION. Copyright 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. All rights reserved. 2 CONTENTS 1. THEOLOGY .............................................................................................................................................. 4 THE NATURE OF THEOLOGY ................................................................................................................ 4 THE POSSIBILITY OF THEOLOGY ........................................................................................................ 5 THE NECESSITY OF THEOLOGY .......................................................................................................... 9 2. SCRIPTURE ............................................................................................................................................. 13 THE NATURE OF SCRIPTURE ............................................................................................................. -

Freedom of the Will and Effectual Calling

FOUNDERS JOURNAL FROM FOUNDERS MINISTRIES | SUMMER 2017 | ISSUE 109 FREEDOM OF THE WILL AND EFFECTUAL CALLING www.founders.org Founders Ministries is committed to encouraging the recovery of the gospel and the biblical reformation of local churches. We believe that the biblical faith is inherently doctrinal, and are therefore confessional in our approach. We recognize the time-tested Second London Baptist Confession of Faith (1689) as a faithful summary of important biblical teachings. The Founders Journal is published quarterly (winter, spring, summer and fall). The journal and other resources are made available by the generous investment of our supporters. You can support the work of Founders Ministries by giving online at: founders.org/give/ Or by sending a donation by check to: Founders Ministries PO Box 150931 Cape Coral, FL 33915 All donations to Founders Ministries are tax-deductible. Please send all inquiries and correspondence for the Founders Journal to: [email protected] Or contact us by phone at 239-772-1400. Visit our web site for an online archive of past issues of the Founders Journal. Contents Introduction: Are Explanations Irrelevant? Tom Nettles Page 4 Of Free WIll 1689 London Baptist Confession: Chapter IX Reagan Marsh Page 7 Of Effectual Calling 1689 London Baptist Confession: Chapter X Eric Smith Page 18 Infant Election 1689 London Baptist Confession: Chapter X, Paragraph 3 Obbie Todd Page 28 Book Review The Extent of the Atonement by David Allen Reviewed by Jeff Johnson Page 39 The Founders Journal 3 Tom Nettles Introduction Are Explanations Irrelevant? How do human free agency and responsibility relate to divine effectuality? This question sets up one of the most challenging discussions in theological literature. -

5 Points of Calvinism – Lesson 9 (Part 1)

5 Points of Calvinism – Lesson 9 (Part 1) Sinners God Christ Spirit Saints Preservation of the saints [email protected] 5 Points of Calvinism - TULIP God is holy, righteous and loving Let God be God, and God will do what God wills Jesus calls His own sheep by name The Spirit gives life and seals the elects The Father’s hand and The Son’s hand protect us [email protected] Summary of Irresistible Grace Effectual Calling Efficacious calling for the elects for a divine purpose Decisive calling that leads an elect to repentance and faith in Jesus Christ Conclusive calling that brings about justification and sanctification of the believer Perseverance of the Saints Once saved, always saved Eternal Security Preservation of God for the Saints Can a believer lose his salvation? What about those who fall away? Can a believer lose his salvation? 1. No, because "Salvation is of The Lord” If we own these: Misplaced them Dropped them Stolen Jonah Salvation belongs to the Lord! (Jonah 2:9b) David Salvation belongs to the Lord; (Ps 3:8a) 9 After this I looked, and behold, a great multitude that no one could number, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, clothed in white robes, with palm branches in their hands, 10 and crying out with a loud voice, “Salvation belongs to our God who sits on the throne, and to the Lamb!” (Rev 7:9-10) …..Salvation and glory and power belong to our God, (Rev 19:1b) If salvation or saving faith belongs to me, I will lose them somehow A true believer in Jesus Christ will NEVER lose his salvation ! Can a believer lose his salvation? 2. -

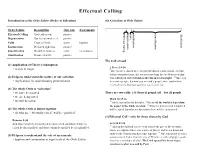

Effectual Calling

Effectual Calling Introduction to the Ordo Salutis (Order of Salvation) (6) A timeline of Ordo Salutis Ordo Salutis Description Our role Sacraments |--------------------|-----|-------------------------------------------------| Sanctification Glorification Effectual Calling Faith Regeneration Effectual Calling God calls us out passive Justification Regeneration Our hearts awakened passive Faith Trust in Christ active baptism Justification Declared righteous passive Sanctification Growth in holiness active communion Glorification Resurrected life passive The Call of God (1) Application of Christ’s redemption 1 Peter 2:9-10 • occurs in stages 9 But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession, that you may proclaim the excellencies of him (2) Helps us understand the nature of our salvation who called you out of darkness into his marvelous light. 10 Once you • implications for understanding predestination were not a people, but now you are God’s people; once you had not received mercy, but now you have received mercy. (3) The whole Ordo is “salvation” • we have been saved There are two calls: (1) General gospel call – for all people • we are being saved Mark 16:15-16 • we will be saved 15 And Jesus said to his disciples, “Go into all the world and proclaim the gospel to the whole creation. 16 Whoever believes and is baptized (4) The whole Ordo is linked together will be saved, but whoever does not believe will be condemned.” • all who are “effectually called” will be “glorified” (2) Effectual Call – only for those chosen by God Romans 8:30 And those whom he predestined he also called, and those whom he Acts 16:13-14 13 called he also justified, and those whom he justified he also glorified. -

A Study of the Shorter Catechism Effectual Calling Question 31: What Is Effectual Calling?

From Your Pastor A Study of the Shorter Catechism Effectual Calling Question 31: What is effectual calling? Answer: Effectual calling is the work of God's Spirit,(1) whereby, convincing us of our sin and misery,(2) enlightening our minds in the knowledge of Christ,(3) and renewing our wills,(4) he doth persuade and enable us to embrace Jesus Christ, freely offered to us in the gospel.(5) (1)2 Tim 1:9; 2 Thess. 2:13,14 (2)Acts 2:37 (3)Acts 26:18 (4)Ezek. 36:26,27 (5)John 6:44,45; Phil. 2:13 Scripture Memory: “And those whom he predestined he also called, and those whom he called he also justified, and those whom he justified he also glorified” (Romans 8:30). An Explanation: God calls sinners to Himself with a general call as well as a specifically effectual call. Both are the works of God’s Spirit. The general call is a work of God’s Spirit in the sphere of common grace and this call can be resisted by sinners (Acts 5:33; 7:51-54). The effectual call is a work of God’s Spirit in the sphere of special grace that always results in powerfully making dead and sinful hearts alive (Ezek. 36:26-27; Eph. 2:4-6), and beginning the work of restoring the image of God in man in the sinner’s union with Christ (Col. 3:10; Acts 2:37-39). Effectual calling can be illustrated in Jesus’ raising Lazarus from the dead. Until Jesus called Lazarus, he was dead and unable to respond to Jesus’ call. -

The Holy Spirit PASTOR FRED GRECO Holy Spirit & Regeneration WEEK 6 – PART 2

The Holy Spirit PASTOR FRED GRECO Holy Spirit & Regeneration WEEK 6 – PART 2 Review: Order of Salvation Glorification Sanctification Justification Faith Adoption Regeneration Repentance Effectual Calling Election Regeneration is Not: Not baptism Not moral reformation Regeneration is: The creation of a new creature The knowledge of God The Cause and Means of Regeneration How Can We Be Saved? . What is our nature? . Impossible to turn to God (Jer. 13:23) . Holy Spirit is immediate author of this work (John 3:3f.) How Can We Be Saved? . NO possibility of salvation to those living and dying in a state of sin . Deliverance only by regeneration (Romans 3:13) The Holy Spirit and Effectual Calling Effectual Call & New Birth Holy Spirit & Effectual Calling What does the Spirit • We need our minds do in His call? enlightened • We need our wills What do we need? renewed • We need our affections set right Holy Spirit & Effectual Calling Delivering you from your people For God, who said, “Let and from the Gentiles—to whom I am sending you to open light shine out of their eyes, so that they may turn darkness,” has shone in from darkness to light and from our hearts to give the the power of Satan to God, that light of the knowledge of they may receive forgiveness of sins and a place among those the glory of God in the who are sanctified by faith in face of Jesus Christ. (2 me. (Acts 26:17–18) Corinthians 4:6) Convincing of Sin and Misery Spirit’s Task – John 16:8 Uses the Law – Romans 3:20 In action – Acts 2:36-37 Enlightening Our Minds Lost in the Fall . -

That God May Be All in All: a Paterology Demonstrating That the Father Is the Initiator of All Divine Activity

Copyright © 2016 Ryan Lowell Rippee All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. THAT GOD MAY BE ALL IN ALL: A PATEROLOGY DEMONSTRATING THAT THE FATHER IS THE INITIATOR OF ALL DIVINE ACTIVITY __________________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________ by Ryan Lowell Rippee December 2016 APPROVAL SHEET THAT GOD MAY BE ALL IN ALL: A PATEROLOGY DEMONSTRATING THAT THE FATHER IS THE INITIATOR OF ALL DIVINE ACTIVITY Ryan Lowell Rippee Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Bruce A. Ware (Chair) __________________________________________ James M. Hamilton __________________________________________ Stephen J. Wellum Date______________________________ I dedicate this dissertation to my family: my parents, Chris and Joni Rippee; my in-laws John and Pam Fernandez; my siblings and in-laws; my nephews and nieces (all 21 of them!); and especially my wife, Jennafer, and our children, Gavin, Delaney, Liam, Caedmon, and Ainsley. I love you all very much and am most grateful for your support and patience during these four years. I also want to dedicate this dissertation to the memory of my brother-in-law, Yuri Trebotich, who went home to be with the Lord Jesus this year, and -

HTPC Summer 2019 OPENING ASSEMBLY Week 11 Review: Memory Verse #1 for Here We Have No Lasting City, but We Seek the City That Is to Come

The Pilgrim’s Progress HTPC Summer 2019 OPENING ASSEMBLY Week 11 Review: Memory Verse #1 For here we have no lasting city, but we seek the city that is to come. (Hebrews 13:14) 2 Review: Memory Verse #2 Beloved, I urge you as sojourners and exiles to abstain from the passions of the flesh, which wage war against your soul. (1 Peter 2:11) 3 LEARN TODAY: Memory Verse #3 Hebrews 11:13-16 “These all died in faith, not having received the things promised, but having seen them and greeted them from afar, and having acknowledged that they were strangers and exiles on the earth. For people who speak thus make it clear that they are seeking a homeland. If they had been thinking of that land from which they had gone out, they would have had opportunity to return. But as it is, they desire a better country, that is, a heavenly one. Therefore God is not ashamed to be called their God, for he has prepared for them a city.” 4 The Cross 1. Jesus, You hung on the cross to take my burden from me. It rolled into the open tomb, and I'm forever free! Jesus, what You bore, was wrath that was meant for me. Oh, how can I describe such love as You, Lord, have for me? 2. Jesus, You hung on the cross to give me raiment so new. You took the rags I wore with shame, oh Savior faithful and true. You now call me Your own, and I gladly call You "Lord." And if there be any good in me, it's only because of You. -

Theological Conviction Statement SWFL Presbytery July

The Presbytery of Please submit to: Southwest Florida The Examination Committee ! [email protected], ! 863-605-2363, Chairman ! ! !Theological Conviction Statement !Your Name: ____John Larson________________ Date: ____July 28, 2014_________ ! Part One: Theological Views Please state briefly your personal views on the following subjects: 1. The Inspiration and Canonicity of Scripture ! “All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be competent, !equipped for every good work” (2 Tim 3.16-17). ! When Paul uses the Word “theopneustos” he is talking about the origin of Scripture. God is truly the author of Scripture. “All Scripture” is the product of the breath of God. It is as if God exhaled and the product of his exhaling is the Bible. Whatever Scripture !says, God says.! “…no prophecy of Scripture comes from someone's own interpretation. For no prophecy was ever produced by the will of man, but men spoke from God as they were !carried along by the Holy Spirit” (2 Peter 1.20-21).! The Bible is “from God”. It is not the result of someone’s effort to makes sense of reality, !nor is it the result of human initiative.! “And we also thank God constantly for this, that when you received the Word of God, which you heard from us, you accepted it not as the Word of men but as what it really is, !the Word of God, which is at work in you believers” (1 Thessalonians 2.13).! Because of the Bible’s origin, it’s ‘from God’ character, it and it alone is our rule of faith and practice. -

Wisdom of Gospel

The Wisdom of the Gospel: Effectual Calling (& Regeneration) Think About It— When and how does the unregenerate (not born again) sinner, incapable of faith (see 1 Cor. 2:14), take on the condition where faith is possible? Talk About It— Ordo Salutis (order of salvation)—the (sometimes) temporal but (more often) logical or causal order in which God applies salvation to us. Regeneration— “...the work of God which gives new life to the one who believes” (Ryrie). General Calling of the Gospel—the general preaching of the gospel to those who respond in faith, as well as those who don’t. Effectual Calling— “...an act of God the Father, speaking through the human proclamation of the gospel, in which he summons people to himself in such a way that they respond in saving faith” (Grudem). Four possible answers to our “hook” question— Possibility #1: We’re really not that sinful and can respond to God on our own apart from a special work of grace (Semi-Pelagianism/Cassianism). Possibility #2: Christ enabled faith by changing the spiritual condition of everyone at the cross (the Arminian doctrine of “prevenient grace”). Possibility #3: God regenerates the elect before conversion so that they can believe (Reformed theology). Possibility #4: God effectually calls the elect to faith through the gospel, then regenerates those who believe (Faith Bible Church). Effectual Calling— 1. Effectual calling is entirely from _______________ (Rm. 8:30; 2 Tim. 1:8-9) and is the work of the _______________ (1 Cor. 2:10-16). 2. In effectual calling God removes us from _______________ (1 Pet.