Kuzhikkanam (Tomb-Fee & Land Tenure)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

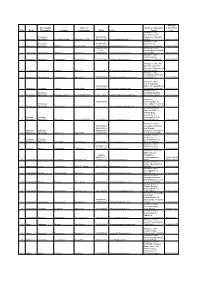

Sl.No. Block Panchayath/ Municipality Location Name of Entrepreneur Mobile E-Mail Address of Akshaya Centre Akshaya Centre Phone

Akshaya Panchayath/ Name of Address of Akshaya Centre Phone Sl.No. Block Municipality Location Entrepreneur Mobile E-mail Centre No Akshaya e centre, Chennadu Kavala, Erattupetta 9961985088, Erattupetta, Kottayam- 1 Erattupetta Municipality Chennadu Kavala Sajida Beevi. T.M 9447507691, [email protected] 686121 04822-275088 Akshaya e centre, Erattupetta 9446923406, Nadackal P O, 2 Erattupetta Municipality Hutha Jn. Shaheer PM 9847683049 [email protected] Erattupetta, Kottayam 04822-329714 9645104141 Akshaya E-Centre, Binu- Panackapplam,Plassnal 3 Erattupetta Thalappalam Pllasanal Beena C S 9605793000 [email protected] P O- 686579 04822-273323 Akshaya e-centre, Medical College, 4 Ettumanoor Arpookkara Panampalam Renjinimol P S 9961777515 [email protected] Arpookkara, Kottayam 0481-2594065 Akshaya e centre, Hill view Bldg.,Oppt. M G. University, Athirampuzha 5 Ettumanoor Athirampuzha Amalagiri Shibu K.V. 9446303157 [email protected] Kottayam-686562 0481-2730349 Akshaya e-centre, , Thavalkkuzhy,Ettumano 6 Ettumanoor Athirampuzha Thavalakuzhy Josemon T J 9947107199 [email protected] or P.O-686631 0418-2536494 Akshaya e-centre, Near Cherpumkal 9539086448 Bridge, Cherpumkal P O, 7 Ettumanoor Aymanam Valliyad Nisha Sham 9544670426 [email protected] Kumarakom, Kottayam 0481-2523340 Akshaya Centre, Ettumanoor Municipality Building, 8 Ettumanoor Muncipality Ettumanoor Town Reeba Maria Thomas 9447779242 [email protected] Ettumanoor-686631 0481-2535262 Akshaya e- 9605025039 Centre,Munduvelil Ettumanoor -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 29.05.2018To05.05.2018

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 29.05.2018to05.05.2018 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Parasseril House, Near Cr 572/18 Sabu K S Si Of Homeo Colleg Bhagom, 03.05.18 1 Sijo CS Sasi 33/18 M Police Station U/S 279,338 CHRY Police Bail from PS Sachivothamapuram, 11.00 Am IPC Changanacherrry Kurichi Cr 1028/18 Puthenthodu, Shameer Khan JFMC I Court 04.05.18 U/S 20 (b) (ii)A 2 Reji Govinedan 55/18 M Chingavanam, Police Station CHRY Si Of Police Changanacherr 06.30 Pm of NDPS Act, 77 Changanacherry Changanacherrry y of JJ ACT Cr 1028/18 Ratheesh bhavan, Shameer Khan JFMC I Court 04.05.18 U/S 20 (b) (ii)A 3 Ratheesh Rajan 39/18 M Puthenpalam, Police Station CHRY Si Of Police Changanacherr 06.30 Pm of NDPS Act, 77 Chingavanam Changanacherrry y of JJ ACT Pramodam Cr 1021/18 Shameer Khan Prabhakaran 06.05.18 4 Kesavan Pillai 66/18 M House,Perunna PO, Police Station U/S 279,338 CHRY Si Of Police Bail from PS Nair 12.30 Pm Changanaherry IPC Changanacherrry THANIKKAPADI ROBIN Cr. 650/18 279 RANEESH TS PHILIP T HOUSE, 29.04.18, BAIL FROM 5 JOSEPH M-32 KANJIKUZHY IPC AND 185 Kottayam east SI KOTTAYAM JOSEPH VADAVATHOOR, 16.15 Hrs PS PHILIP MV ACT EAST KOTTAYAM KURISUKUNNEL (H) Cr. -

Coconut Producers Federations (CPF) - KOTTAYAM District, Kerala

Coconut Producers Federations (CPF) - KOTTAYAM District, Kerala Sl No.of No.of Bearing Annual CPF Reg No. Name of CPF and Contact address Panchayath Block Taluk No. CPSs farmers palms production Madappalli, FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETIES Thrikkodithanam, CHAGANASSERY WEST President: Shri Jose Mathew 1 CPF/KTM/2015-16/008 Payippad, Vazhappalli, Madappalli Changanassery 10 1339 40407 2002735 Iyyalil Vadakkelil, Madapalli PO, Kottayam Pin:686646 Kuruchi, Changanassery Mobile:7559080068 Municipality Kangazha, CHANGANASSERY REGIONAL FEDERATION OF Nedumkunnam, COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETIES President: V.J Vazhoor, 2 CPF/KTM/2013-14/001 Karukachal, Madappally, Changanassery 21 2268 69431 2531185 Varghese Thattaradiyil,Karukachal P.O Pin:686540 Madappally Vazhapally, Kurichi and Mobile:9388416569 Vakathanam REGIONAL FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS Vellavoor, Manimala, SOCIETY MANIMALA President: Shri Gopinatha Kurup Vazhoor,Kanjira Changanassery 3 CPF/KTM/2015-16/009 Vazhoor, Chirakadavu, 10 1425 40752 1133040 Puthenpurekkal Erathuvadakara P.O Manimala ppilly ,Kanjirappilly Elikkulam Pin:686543 Mobile:9447128232 FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETIES UPPER KUTTANADU President: Shri.P.V Jose 4 CPF/KTM/2015-16/017 Arpookkara, Neendoor Ettumanoor Kottayam 8 633 40986 1486162 Palamattam, Amalagiri P.O, Kottayam Pin:686561 Mobile:9496160954 Email:[email protected] KUMARAKOM FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETIES President: Jomon M.Joseph Kumarakom, Thiruvarp, 5 CPF/KTM/2014-15/003 Ettumanoor Kottayam 9 768 49822 2281625 Canal -

2562263 [email protected] PD ATMA

SL No Office Name Address Telephone Number Email-ID Principal Agricultural Officer, Collectorate P.O, 1 Principal Agricultural Office 0481- 2562263 [email protected] kottayam 2 PD ATMA Project Director ATMA, Collectorate P.O, kottayam 0481- 2560569 [email protected] Assistant Director of Agriculture ,Municipal Rest 3 ADA Kottayam 9496000840 [email protected] House Building, Near Boat Jetty, Kottayam - 1 Agriculture Officer,Nattakom Krishibhavan , 4 Krishibhavan Nattakom 0481- 2360105 [email protected] Mariappally P.O PIN 686023 Agriculture Officer,Vijayapuram Krishibhavan , 5 Krishibhavan Vijayapuram 0481-2578060 [email protected] Vadavathoor P.O, Kottayam PIN 686010 Agriculture Officer,Ayarkunnam Krishibhavan , 6 Krishibhavan Ayarkkunnam 0481- 2546133 [email protected] Arumanoor P.O PIN 686509 Agriculture Officer, Puthuppally Krishibhavan 7 Krishibhavan Puthuppally 9496000845 [email protected] Eravilnalloor P.O, Kottayam- 686011 Agriculture Officer, Panachikkad Krishibhavan 8 Krishibhavan Panachikkad Kuzhimattom P.O, Paruthumpara, Kottayam- 0481- 24330353 [email protected] 686533 Agriculture Officer, Krishibhavan ,Kumaranalloor 9 Krishibhavan Kumaranalloor 0481- 2310466 [email protected] P.O, Kottayam- 686016 Agriculture Officer, Krishibhavan ,Kurichy P.O, 10 KrishiBhavan Kurichy 0481-2320307 [email protected] Kottayam- 686532 Agricultural Field Officer, KrishiBhavan Kottayam 11 KrishiBhavan Kottayam(M) Municipality ,Municipal Rest House Building,Near 9496000848 [email protected] Boat -

Unni Madhu 30/19 Nalupankilchi Ra House

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 17.02.2019to23.02.2019 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 RADHAKRIS 208/19, HNAN NAIR NALUPANKILCHI 279 IPC & SI OF Bail from 1 UNNI MADHU 30/19 RA HOUSE, KANJIRAM JN17.02.2019 Kumarakom 185 OF MV POLICE PS KUMARAKOM ACT KUMARAKA M G 209/19, RAJANKUM KUTTIKATTU 279 IPC & AR SI OF Bail from 2 SUBHASH SURENDRAN 31/19 HOUSE, CHANDAKAVALA17.02.2019 Kumarakom 185 OF MV POLICE PS KUMARAKOM ACT KUMARAKA M G 210/19, RAJANKUM MUDAKKALIL PURUSHOT 279 IPC & AR SI OF Bail from 3 ANEESH 32/19 HOUSE, CHANDAKAVALA17.02.2019 Kumarakom HAMAN 185 OF MV POLICE PS KUMARAKOM ACT KUMARAKA M RADHAKRIS 211/19, HNAN NAIR MADHAVA PUTHUCHIRA 279 IPC & SI OF Bail from 4 PRASAD 49/19 KANNADICHAL17.02.2019 Kumarakom N CHENGALAM 185 OF MV POLICE PS ACT KUMARAKA M G RAJANKUM VADYAMPARAM 212/19, AR SI OF Bail from 5 RAJESH RAJU 21/19 BU HOUSE, CHANDAKAVALA17.02.2019 Kumarakom 107 CRPC POLICE PS VELOOR KUMARAKA M G PALATHANATHU 213/19, RAJANKUM HOUSE, 279 IPC & Kumarako AR SI OF Bail from 6 SREEEJITH THAMPI 25/19 CHAKRAMPADY18.02.2019 VARANADU 185 OF MV m POLICE PS CHERTHALA ACT KUMARAKA M RADHAKRIS 214/19, HNAN NAIR KALATHIL 279 IPC & Kumarako SI OF Bail from 7 MADHUI DAMU 48/19 HOPUSE, BOATJETTY 18.02.2019 185 OF MV m POLICE PS KUMARAKJOM ACT KUMARAKA M RADHAKRIS 215/19, HNAN -

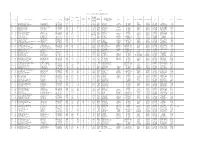

Sheet1 Page 1 LIST of SCHOOLS in KOTTAYAM DISTRICT 10 Sl. No

Sheet1 LIST OF SCHOOLS IN KOTTAYAM DISTRICT No of Students HS/HSS/ Year of VHSS/H Name of Panch- Std. Std. Boys/ 10 Sl. No. Name of School Address with Pincode Phone No Establishm SS ayat /Muncipality/ Block Taluk Name of Parliament Name of Assembly DEO AEO MGT Remarks (From) (To) Girls/ Mixed ent Boys Girls &VHSS/ Corporation TTI 10 1 Areeparambu Govt. HSS Areeparambu P.O. 0481-2700300 1905 42 36 I XII HSS Mixed Manarcadu Pallam Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Pampady Govt 10 2 Arpookara Medical College VHSS Gandhinagar P.O. 0481-2597401 1966 73 33 V XII HSS&VHSS Mixed Arpookara Ettumanoor Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Kottayam West Govt 10 3 Changanacherry Govt. HSS Changanacherry P.O. 0481-2420748 1871 43 23 V XII HSS Mixed Changanacherry ( M ) Changanacherry Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Changanassery Govt 10 4 Chengalam Govt. HSS Chengalam South P.O. 0481-2524828 1917 127 107 I XII HSS Mixed Thiruvarpu Pallam Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Kottayam West Govt 10 5 Karapuzha Govt. HSS Karapuzha P.O. 0481-2582936 1895 56 34 I XII HSS Mixed Kottayam( M ) Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Kottayam West Govt 10 6 Karipputhitta Govt. HS Arpookara P.O. 0481-2598612 1915 74 44 I X HS Mixed Arpookara Ettumanoor Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Kottayam West Govt 10 7 Kothala Govt. VHSS S.N. Puram P.O. 0481-2507726 1912 48 64 I XII VHSS Mixed Kooroppada Pampady Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Pampady Govt 10 8 Kottayam Govt. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 14.06.2020To20.06.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 14.06.2020to20.06.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 KALIYICKAL H, Cr. No. 719/20 ANANDHU UNNIKRISHAN THUKALASSERY NEAR POSR KOTTAYAM 1 20 14.06.20 U/S 279 IPC & SREEJITH T BAIL FROM PS KRISHANAN AN BHAGOM, OFFICE WEST PS 06:40 Hrs 132(1)/179 IPC THIRUVALLA KALARICKAL H, Cr. No. 720/20 KOTTAYAM 2 DEEPU VENUGOPAL 21 MOOLAVATTOM PO, STAR Jn. 14.06.20 U/S 279 IPC & SABU SUNNY BAIL FROM PS WEST PS NATTAKOM 10:30 Hrs 118(E) KP Act Cr. No. 721/20 THUMPAMALIYIL H, U/S KOTTAYAM 3 NIKHIL TR KOCHUMON 20 MOOLAVATTOM PO, AIDA Jn. 14.06.20 2336,269,291 SABU SUNNY BAIL FROM PS WEST PS NATTAKOM 11:00 Hrs IPC & 4(2)(a) OF KEPDO KIZHAKKENAKATHU H, Cr. No. 726/20 KOTTAYAM JFMC 1 4 JOJO JOYIN 23 MANARKADU , BAKER Jn. 15.06.20 U/S 20(B)ii(A) SUMESH T WEST PS KOTTAYAM KOTTAYAM 18:45 Hrs NDPS Act. KANAKKANIL H, Cr. No. 726/20 KOTTAYAM JFMC 1 5 JOMON KURIAKOSE 27 KALLUPURAYKAL H, BAKER Jn. 15.06.20 U/S 20(B)ii(A) SUMESH T WEST PS KOTTAYAM VELOOR 18:45 Hrs NDPS Act. -

KSEB Electrical Section Codes

SMS Format -> KSEB <Space> Section Code<Space> Consumer No -> 537252 KSEB Electrical Section Codes Section Code Electrical Section Name 5617 Adimali 4609 Adoor 6516 Agali 6648 Alakode 6521 Alanellur 5501 Alappuzha ( North) 5502 Alappuzha (Town) 5503 Alappuzha(South) 6574 Alathiyoor 6509 Alathur 5568 Aluva North 5567 Aluva Town 5569 Aluva West 6534 Ambalappara 5505 Ambalappuzha 6762 Ambalavayal 4656 Amboori 5670 Ammadam 6756 Anakkayam 4597 Anchal 4669 Anchal (West) 6748 Angadipuram 5579 Angamaly. 5648 Annamanada 5553 Arakkunnam 5535 Aranmula 6789 Areekkad 6767 Areekkulam 6549 Areekode 5679 Arimboor 5705 Arookutty 5515 Aroor 5518 Arthinkal 4652 Aryanad 5572 Athani 4664 Athirampuzha 6615 Atholy 4531 Attingal. 4532 Avanavanchery. 4632 Ayarkunnam 4565 Ayathil. 6624 Ayenchery 4629 Aymanam 4591 Ayoor 4608 Ayroor 5678 Ayyanthole 6662 Azhikode 6743 Azhiyoor 6690 Badiadkka 6773 Balamthode 4542 Balaramapuram 6613 Balussery 6603 Beach 5699 Beach, Guruvayoor Page 1 of 13 SMS Format -> KSEB <Space> Section Code<Space> Consumer No -> 537252 4513 Beach, Trivandrum 6635 Beypore 5627 Bharananganam 6697 Bheemanady 5702 Big Bazar 6518 Bigbazar 6655 Burnassery 4558 Cantonment, Kollam 4506 Cantonment. 6602 Central, Kozhikode 4672 Chadayamangalam 6660 Chakkarakkal 6716 Chakkittapara 5651 Chalakudy 6538 Chalissery 6661 Chalode 5508 Champakulam 4636 Changanacherry 6585 Changaramkulam 6745 Chapparappadavu 5527 Charummood 4575 Chathannoor. 6772 Chattanchal 6708 Chattiparamba 5698 Chavakkad 4571 Chavara. 5691 Chelakkara 6744 Chelannur 6577 Chelari 6721 Chemperi 4644 -

Vaikom Assembly Kerala Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/KR-095-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5313-616-1 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 130 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) at a Glance | Features of Assembly 1-2 as per Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) in 2 District | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary 3-9 Constituency -(Lok Sabha) | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-11 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages -

Slno Folio/Demat No. Name of Shareholder Address Shares 00001 1203280000051508 Jasmin Mathew

SLNO FOLIO/DEMAT NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDER ADDRESS SHARES 00001 1203280000051508 JASMIN MATHEW . CHOYIS GRDEN 29 VYTTILA 156(29/156) COCHIN . 3330 00002 108417 MARIYAM KUNJUVAREED CHUNGAM HOUSE MELOOR PUSHDAGIRI . 0 1250 00003 113579 HAMEED U K RUKHIA MANZIL BABU COMPOUND OMBATHUKERA ULLAR 0 370 00004 109748 PAUL C R CHITTILAPPILLY POZALIPARAMBIL HOUSE KALLAMKUNNU PO NADAVARAMB THRISSUR DT 0 1250 00005 109297 VISWANATHAN C A CHILIPPAT HOUSE PO THRITHALLORE THRICHUR . 0 1250 00006 122266 SATHYASEELAN K SATHYASEELAN KARTHIYAINY VILAS VAZIYAKADA CHIRAYINKIL PO TVM DST KERALA 0 1250 00007 119156 PRASAD K K KUNNATHUNIKATHIL HOUSE PANANGAD P O . 0 1250 00008 128304 SEBASTIAN A G MUTTAVILA HOUSE BHARANICAVU PUNALUR . 0 1250 00009 130972 PAILY P C PANJIKKARAN HOUSE ANGADIKKADAVU ANGAMALY . 0 1250 00010 120801 GEORGE VINOD K KILITHATTIL VEEDU INCHAKADU MYLOM . 0 3750 00011 124097 CHANDRAN P EDAVAM PARABIL HOUSE BAUK ROAD P O ALATHUR . 0 1250 00012 125841 AMINA M S CC 33/149 KANNADIPARAMBIL VENNALA PO ERNAKULAM (DIST) KERALA 0 1250 00013 135203 VASUDEVAN N NADUKANDY HOUSE CHETTIKULAM P O ELATHUR CALICUT 0 370 00014 146558 DEVANAND ALIAS RAMANI INSPECTION ENGINEER (CSD) P BOX 564 DUBAI ELECTRICITY & WATER AUTHORITY DUBAI UAE . 0 500 00015 145616 ANIL KUMAR PANDARATHIL MUKUNDAN AMERICAN LIFE INSURANCE CO OMAN POST BOX NO 894 MUTRAH P C 114 S OF OMAN . 0 250 00016 138602 LIZAMMA SABU JOHN KUZHIYATH HOUSE NEDUMKUNNAM PO KOTTAYAM DT KERALA 0 1250 00017 144954 THAMPY M A AL ZAKI STEEL P B NO 8263 DAMMAM K S A . 0 250 00018 161330 JOSE K M KANATTU HOUSE KOLANI THODUPUZHA IDUKKI DIST 0 10 00019 161636 SATHEESH BABU R C GEETHU NIVAS PANANGADU PUNALOOR . -

CATHOLIC NEAR EAST WELFARE ASSOCIATION Consolidated Financial Statements and Schedules

CATHOLIC NEAR EAST WELFARE ASSOCIATION Consolidated Financial Statements and Schedules December 31, 2014 (With Independent Auditors’ Report Thereon) KPMG LLP 345 Park Avenue New York, NY 10154-0102 Independent Auditors’ Report The Board of Trustees Catholic Near East Welfare Association: We have audited the accompanying consolidated financial statements of Catholic Near East Welfare Association (CNEWA), which comprise the consolidated statement of financial position as of December 31, 2014, and the related consolidated statements of activities, functional expenses and cash flows for the year then ended, and the related notes to the consolidated financial statements. Management’s Responsibility for the Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these consolidated financial statements in accordance with U.S. generally accepted accounting principles; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of consolidated financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. Auditors’ Responsibility Our responsibility is to express an opinion on these consolidated financial statements based on our audit. We conducted our audit in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the consolidated financial statements are free from material misstatement. An audit involves performing procedures to obtain audit evidence about the amounts and disclosures in the consolidated financial statements. The procedures selected depend on the auditors’ judgment, including the assessment of the risks of material misstatement of the consolidated financial statements, whether due to fraud or error. -

2005-06 - Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2005-06 - Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010107052 Shahul Hameed Kinattadivilakathu Puttenveedu,A.V.Street,Balaramapuram 0 M M R Foot Ware And Fancy Store Business Sector 52632 44737 03/05/2005 2 1 010107163 Radhakrishnan K N Neelambaram, Tc. Vi/1042,Kalliyoor,Kalliyur 0 M R Dtp Centre Service Sector 52632 44737 27/04/2005 1 2 010107164 Rajesh Br Ragam, Tc.Viii/1410,Archana Nagar, B-54,Medical College 0 M U Automobile Workshop Service Sector 52632 44737 27/04/2005 1 3 010107168 Sumedan M Thuyoor Karimbu Naduvila Puthen 0 M R Furniture Mart Business Sector 52632 44737 27/04/2005 1 Veedu,Thellukuzhy,Perumkadavila 4 010107171 Sajikumar G Tc.Vpi,67, Roadarikathuveedu,Kannurkonam,Mannamconam 0 M R Ready Made Garments Business Sector 52632 44737 29/04/2005 1 5 010107172 Elsi Bai Tc.14/384, Pottaputhuvalveedu,Karode,Karode 0 F R Furniture Mart Business Sector 47368 40263 30/04/2005 1 6 010107179 Sunilkumar B Tc.Iii/155, Vadakkumkara Puthenveedu,Adi Kottoor,Kottoor 0 M R Winding Business Sector 52632 44737 04/05/2005 1 Tvm 7 010107184 Sudheeshkumar R Tc.Xvii/386, 0 M U Bakery Unit Business Sector 47368 40263 09/05/2005 1 Mannamvilakathuveedu,Thozhukkal,Neyyattinkara 8 010107187 Hari Kumar K Vilayilputhenveedu,Vattiyoorkavu,Kodunganur 0 M R Provision Store Business Sector 52632 44737 10/05/2005 1 9 010107191 Sanalkumar M Chalarathalackalmeleputhenveedu,Peringamala,Kalliyur