12 Years a Slave’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kam Williams, “The “12 Years a Slave” Interview: Steve Mcqueen”, the New Journal and Guide, February 03, 2014

Kam Williams, “The “12 Years a Slave” Interview: Steve McQueen”, The new journal and guide, February 03, 2014 Artist and filmmaker Steven Rodney McQueen was born in London on October 9, 1969. His critically-acclaimed directorial debut, Hunger, won the Camera d’Or at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival. He followed that up with the incendiary offering Shame, a well- received, thought-provoking drama about addiction and secrecy in the modern world. In 1996, McQueen was the recipient of an ICA Futures Award. A couple of years later, he won a DAAD artist’s scholarship to Berlin. Besides exhibiting at the ICA and at the Kunsthalle in Zürich, he also won the coveted Turner Prize. He has exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Documenta, and at the 53rd Venice Biennale as a representative of Great Britain. His artwork can be found in museum collections around the world like the Tate, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Centre Pompidou. In 2003, he was appointed Official War Artist for the Iraq War by the Imperial War Museum and he subsequently produced the poignant and controversial project Queen and Country commemorating the deaths of British soldiers who perished in the conflict by presenting their portraits as a sheet of stamps. Steve and his wife, cultural critic Bianca Stigter, live and work in Amsterdam which is where they are raising their son, Dexter, and daughter, Alex. Here, he talks about his latest film, 12 Years a Slave, which has been nominated for 9 Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director. -

Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South

Antoni Górny Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South Abstract: The so-called blaxploitation genre – a brand of 1970s film-making designed to engage young Black urban viewers – has become synonymous with channeling the political energy of Black Power into larger-than-life Black characters beating “the [White] Man” in real-life urban settings. In spite of their urban focus, however, blaxploitation films repeatedly referenced an idea of the South whose origins lie in antebellum abolitionist propaganda. Developed across the history of American film, this idea became entangled in the post-war era with the Civil Rights struggle by way of the “race problem” film, which identified the South as “racist country,” the privileged site of “racial” injustice as social pathology.1 Recently revived in the widely acclaimed works of Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained) and Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), the two modes of depicting the South put forth in blaxploitation and the “race problem” film continue to hold sway to this day. Yet, while the latter remains indelibly linked, even in this revised perspective, to the abolitionist vision of emancipation as the result of a struggle between idealized, plaintive Blacks and pathological, racist Whites, blaxploitation’s troping of the South as the fulfillment of grotesque White “racial” fantasies offers a more powerful and transformative means of addressing America’s “race problem.” Keywords: blaxploitation, American film, race and racism, slavery, abolitionism The year 2013 was a momentous one for “racial” imagery in Hollywood films. Around the turn of the year, Quentin Tarantino released Django Unchained, a sardonic action- film fantasy about an African slave winning back freedom – and his wife – from the hands of White slave-owners in the antebellum Deep South. -

Obaidi at WHO Committee for Eastern Mediterranean

Amir returns to Obaidi at WHO S Korea cap Kuwait from Committee a miserable positive UN for Eastern week for summit 9 Mediterranean8 Kuwait47 Min 24º Max 39º FREE www.kuwaittimes.net NO: 16662- Friday, October 9, 2015 Bye to Blatter Page 47 In this June 1, 2011 file photo Swiss FIFA President Joseph Blatter, right, and French UEFA President Michel Platini walk together at the 61st FIFA Congress in Zurich, Switzerland. Yesterday FIFA provisionally banned President Sepp Blatter and UEFA President Michel Platini for 90 days. — AP Local FRIDAY, OCTOBER 9, 2015 Local Spotlight Equality is key Life is incompatible here I felt compelled to mention the man’s possible nationality....if he had been Kuwaiti or even an Arab, the circumstances would have been a lot different. Unfortunately, the By Muna Al-Fuzai concept of equality and respecting individuals equally in Kuwait and many other parts in the Arab world remains not fully comprehended. [email protected] By Ahmad Jabr One of the reasons why a search remains stuck in lower tiers in interna- lot of people leave their countries in search of bet- warrant is required - by law - before tional human rights, freedom and traf- ter work, more income, greater stability for their he place: A bystreet near a pri- searching a person is to insure that his ficking in persons reports. It is not a Afamilies and perhaps a chance for fame as well, vate clinic in Jabriya. The time: rights are not violated. Here the law contradiction. when life becomes impossible because of wars and polit- Approximately 10 minutes protects individuals’ rights, but as can ical crises. -

Film Suggestions to Celebrate Black History

Aurora Film Circuit I do apologize that I do not have any Canadian Films listed but also wanted to provide a list of films selected by the National Film Board that portray the multi-layered lives of Canada’s diverse Black communities. Explore the NFB’s collection of films by distinguished Black filmmakers, creators, and allies. (Link below) Black Communities in Canada: A Rich History - NFB Film Info – data gathered from TIFF or IMBd AFC Input – Personal review of the film (Nelia Pacheco Chair/Programmer, AFC) Synopsis – this info was gathered from different sources such as; TIFF, IMBd, Film Reviews etc. FILM TITEL and INFO AFC Input SYNOPSIS FILM SUGGESTIONS TO CELEBRATE BLACK HISTORY MONTH SMALL AXE I am very biased towards the Director Small Axe is based on the real-life experiences of London's West Director: Steve McQueen Steve McQueen, his films are very Indian community and is set between 1969 and 1982 UK, 2020 personal and gorgeous to watch. I 1st – MANGROVE 2hr 7min: English cannot recommend this series Mangrove tells this true story of The Mangrove Nine, who 5 Part Series: ENOUGH, it was fantastic and the clashed with London police in 1970. The trial that followed was stories are a must see. After listening to the first judicial acknowledgment of behaviour motivated by Principal Cast: Gary Beadle, John Boyega, interviews/discussions with Steve racial hatred within the Metropolitan Police Sheyi Cole Kenyah Sandy, Amarah-Jae St. McQueen about this project you see his 2nd – LOVERS ROCK 1hr 10 min: Aubyn and many more.., A single evening at a house party in 1980s West London sets the passion and what this production meant to him, it is a series of “love letters” to his scene, developing intertwined relationships against a Category: TV Mini background of violence, romance and music. -

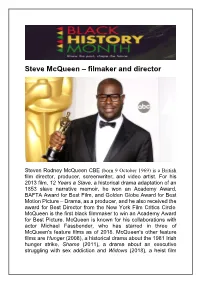

Steve Mcqueen – Filmaker and Director

Steve McQueen – filmaker and director Steven Rodney McQueen CBE (born 9 October 1969) is a British film director, producer, screenwriter, and video artist. For his 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, a historical drama adaptation of an 1853 slave narrative memoir, he won an Academy Award, BAFTA Award for Best Film, and Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, as a producer, and he also received the award for Best Director from the New York Film Critics Circle. McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. McQueen is known for his collaborations with actor Michael Fassbender, who has starred in three of McQueen's feature films as of 2018. McQueen's other feature films are Hunger (2008), a historical drama about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, Shame (2011), a drama about an executive struggling with sex addiction and Widows (2018), a heist film about a group of women who vow to finish the job when their husbands die attempting to do so. McQueen was born in London and is of Grenadianand Trinidadian descent. He grew up in Hanwell, West London and went to Drayton Manor High School. In a 2014 interview, McQueen stated that he had a very bad experience in school, where he had been placed into a class for students believed best suited "for manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." Later, the new head of the school would admit that there had been "institutional" racism at the time. McQueen added that he was dyslexic and had to wear an eyepatch due to a lazy eye, and reflected this may be why he was "put to one side very quickly". -

BFI Poll Reveals UK's Favourite Black Star Performance

BFI POLL REVEALS UK’S FAVOURITE BLACK STAR PERFORMANCE: SIDNEY POITIER AS “MISTER TIBBS” In the Heat of the Night Angela Bassett’s courageous portrayal of Tina Turner in What’s Love Got to Do with It voted as top performance by over 100 industry experts London: (embargoed until 16:30 BST) Thursday 20 October, 2016 – To mark this week’s official launch of its BLACK STAR season, the BFI announced today that Sidney Poitier’s critically-acclaimed and seminal performance as Detective Virgil Tibbs in In the Heat of the Night (dir. Norman Jewison, 1967) has been voted the public’s Favourite Black Star Performance in a poll which included 100 performances spanning over 80 years in film and TV. Running alongside the public poll, a separate poll of over 100 industry experts voted for Angela Bassett’s Oscar®- nominated performance as Tina Turner in What’s Love Got to Do with It (dir. Brian Gibson, 1993). UK Public Poll Pam Grier followed in second place with her terrific turn as the titular character in Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown – an homage to the 1970’s era of Blaxploitation films in America; Michael K. Williams was number three with his unforgettable portrayal of the legendary Omar Little, the openly gay, notorious stick-up man with a strict moral code feared by drug dealers across the city of Baltimore, in the socially and politically charged hit television series The Wire. British actor Chiwetel Ejiofor followed in fourth with his visceral portrayal of Solomon Northup, his break-out performance in Steve McQueen’s ground-breaking, Oscar®-winning true story, 12 Years A Slave; and Morgan Freeman rounded out the top five with his acclaimed, quiet and layered performance in Frank Darabont’s Oscar®-nominated cult classic, The Shawshank Redemption. -

Widescreen Weekend 2008 Brochure (PDF)

A5 Booklet_08:Layout 1 28/1/08 15:56 Page 41 THIS IS CINERAMA Friday 7 March Dirs. Merian C. Cooper, Michael Todd, Fred Rickey USA 1952 120 mins (U) The first 3-strip film made. This is the original Cinerama feature The Widescreen Weekend continues to welcome all which launched the widescreen those fans of large format and widescreen films – era, and is about as fun a piece of CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, Cinerama and IMAX – Americana as you are ever likely and presents an array of past classics from the vaults of to see. More than a technological curio, it's a document of its era. the National Media Museum. A weekend to wallow in the nostalgic best of cinema. HAMLET (70mm) Sunday 9 March Widescreen Passes £70 / £45 Dir. Kenneth Branagh GB/USA 1996 242 mins (PG) Available from the box office 0870 70 10 200 Kenneth Branagh, Julie Christie, Derek Jacobi, Kate Winslet, Judi Patrons should note that tickets for 2001: A Space Odyssey are priced Dench, Charlton Heston at £10 or £7.50 concessions Anyone who has seen this Hamlet in 70mm knows there is no better-looking version in colour. The greatest of Kenneth Branagh’s many achievements so 61 far, he boldly presents the full text of Hamlet with an amazing cast of actors. STAR! (70mm) Saturday 8 March Dir. Robert Wise USA 1968 174 mins (U) Julie Andrews, Daniel Massey, Richard Crenna, Jenny Agutter Robert Wise followed his box office hits West Side Story and The Sound of Music with Star! Julie 62 63 Andrews returned to the screen as Gertrude Lawrence and the film charts her rise from the music hall to Broadway stardom. -

The Statement

THE STATEMENT A Robert Lantos Production A Norman Jewison Film Written by Ronald Harwood Starring Michael Caine Tilda Swinton Jeremy Northam Based on the Novel by Brian Moore A Sony Pictures Classics Release 120 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS SHANNON TREUSCH MELODY KORENBROT CARMELO PIRRONE ERIN BRUCE ZIGGY KOZLOWSKI ANGELA GRESHAM 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, 550 MADISON AVENUE, SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 8TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 NEW YORK, NY 10022 PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com THE STATEMENT A ROBERT LANTOS PRODUCTION A NORMAN JEWISON FILM Directed by NORMAN JEWISON Produced by ROBERT LANTOS NORMAN JEWISON Screenplay by RONALD HARWOOD Based on the novel by BRIAN MOORE Director of Photography KEVIN JEWISON Production Designer JEAN RABASSE Edited by STEPHEN RIVKIN, A.C.E. ANDREW S. EISEN Music by NORMAND CORBEIL Costume Designer CARINE SARFATI Casting by NINA GOLD Co-Producers SANDRA CUNNINGHAM YANNICK BERNARD ROBYN SLOVO Executive Producers DAVID M. THOMPSON MARK MUSSELMAN JASON PIETTE MICHAEL COWAN Associate Producer JULIA ROSENBERG a SERENDIPITY POINT FILMS ODESSA FILMS COMPANY PICTURES co-production in association with ASTRAL MEDIA in association with TELEFILM CANADA in association with CORUS ENTERTAINMENT in association with MOVISION in association with SONY PICTURES -

Solomon Northup and 12 Years a Slave

Solomon Northup and 12 Years a Slave How to analyze slave narratives. Who Was Solomon Northup? 1808: Born in Minerva, NewYork Son of former slave, Mintus Northup; Northup's mother is unknown. 1829: Married Anne Hampton, a free black woman. They had three children. Solomon was a farmer, a rafter on the Lake Champlain Canal, and a popular local fiddler. What Happened to Solomon Northup? Met two circus performers who said they needed a fiddler for engagements inWashington, D.C. Traveled south with the two men. Didn't tell his wife where he was going (she was out of town); he expected to be back by the time his family returned. Poisoned by the two men during an evening of social drinking inWashington, D.C. Became ill; he was taken to his room where the two men robbed him and took his free papers; he vaguely remembered the transfer from the hotel but passed out. What Happened…? • Awoke in chains in a "slave pen" in Washington, D.C., owned by infamous slave dealer, James Birch. (Note: A slave pen were where (Note:a slave pen was where slaves were warehoused before being transported to market) • Transported by sea with other slaves to the New Orleans slave market. • Sold first toWilliam Prince Ford, a cotton plantation owner. • Ford treated Northup with respect due to Northup's many skills, business acumen and initiative. • After six months Ford, needing money, sold Northup to Edwin Epps. Life on the Plantation Edwin Epps was Northup’s master for eight of his 12 years a slave. -

In 1841, Solomon Northup Is a Free African-American Man Working As a Violinist, Living Happily with His Wife and Two Children in Saratoga Springs, New York

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 123 2nd International Conference on Education, Sports, Arts and Management Engineering (ICESAME 2017) What should we do when all is lost? -“Twelve Years A Slave” Ou Lanhua Haikou College of Economics, Haikou City, Hainan Province, 570102, China [email protected] Key words: Northup, free man, runaway slave, Platt, slavery, restore to freedom Abstract: The movie of Twelve Years A Slave tells us a dreadful, but also an inspiring story. Solomon is a fabulous character in the film. At first, he had a decent and elegant life. After being kidnapped as a slave, he chooses forbearance and perseverance with a strong determination. After being enslaved for 12 years, Northup is restored to freedom and returned to his family. Introduction In 1841, Solomon Northup is a free African-American man working as a violinist, living happily with his wife and two children in Saratoga Springs, New York. Two white men, Brown and Hamilton, offer him short-term employment as a musician if he will travel with them to Washington, D.C. However, once they arrive, they drug Northup and conspire to deliver him to a slave pen (American slavery) run by a man named Burch. Northup is later shipped to New Orleans along with others who have been detained against their will. A slave trader named Freeman gives Northup the identity of "Platt", a runaway slave from Georgia, and sells him to plantation owner William Ford. Due to tension between Northup and another plantation worker, Ford sells him to another slave owner named Edwin Epps, called Nigger Breaker. -

Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South

Antoni Górny Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South Abstract: The so-called blaxploitation genre – a brand of 1970s film-making designed to engage young Black urban viewers – has become synonymous with channeling the political energy of Black Power into larger-than-life Black characters beating “the [White] Man” in real-life urban settings. In spite of their urban focus, however, blaxploitation films repeatedly referenced an idea of the South whose origins lie in antebellum abolitionist propaganda. Developed across the history of American film, this idea became entangled in the post-war era with the Civil Rights struggle by way of the “race problem” film, which identified the South as “racist country,” the privileged site of “racial” injustice as social pathology.1 Recently revived in the widely acclaimed works of Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained) and Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), the two modes of depicting the South put forth in blaxploitation and the “race problem” film continue to hold sway to this day. Yet, while the latter remains indelibly linked, even in this revised perspective, to the abolitionist vision of emancipation as the result of a struggle between idealized, plaintive Blacks and pathological, racist Whites, blaxploitation’s troping of the South as the fulfillment of grotesque White “racial” fantasies offers a more powerful and transformative means of addressing America’s “race problem.” Keywords: blaxploitation, American film, race and racism, slavery, abolitionism The year 2013 was a momentous one for “racial” imagery in Hollywood films. Around the turn of the year, Quentin Tarantino released Django Unchained, a sardonic action- film fantasy about an African slave winning back freedom – and his wife – from the hands of White slave-owners in the antebellum Deep South. -

Bullitt, Blow-Up, & Other Dynamite Movie Posters of the 20Th Century

1632 MARKET STREET SAN FRANCISCO 94102 415 347 8366 TEL For immediate release Bullitt, Blow-Up, & Other Dynamite Movie Posters of the 20th Century Curated by Ralph DeLuca July 21 – September 24, 2016 FraenkelLAB 1632 Market Street FraenkelLAB is pleased to present Bullitt, Blow-Up, & Other Dynamite Movie Posters of the 20th Century, curated by Ralph DeLuca, from July 21 through September 24, 2016. Beginning with the earliest public screenings of films in the 1890s and throughout the 20th century, the design of eye-grabbing posters played a key role in attracting moviegoers. Bullitt, Blow-Up, & Other Dynamite Movie Posters at FraenkelLAB focuses on seldom-exhibited posters that incorporate photography to dramatize a variety of film genres, from Hollywood thrillers and musicals to influential and experimental films of the 1960s-1990s. Among the highlights of the exhibition are striking and inventive posters from the mid-20th century, including the classic films Gilda, Niagara, The Searchers, and All About Eve; Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious, Rear Window, and Psycho; and B movies Cover Girl Killer, Captive Wild Woman, and Girl with an Itch. On view will be many significant posters from the 1960s, such as Russ Meyer’s cult exploitation film Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill!; Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up; a 1968 poster for the first theatrical release of Un Chien Andalou (Dir. Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, 1928); and a vintage Japanese poster for Buñuel’s Belle de Jour. The exhibition also features sensational posters for popular movies set in San Francisco: the 1947 film noir Dark Passage (starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall); Steve McQueen as Bullitt (1968); and Clint Eastwood as Dirty Harry (1971).