Tawny Owl MS Revised Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEEDBACK 44 - AUTUMN 2010 the BARN OWL TRUST - CONSERVING the BARN OWL and ITS ENVIRONMENT Welcome to Feedback - It’S Been Another Busy Summer Here at the Trust

Issue Number 44 - Autumn 2010 Waterleat, Ashburton, Devon TQ13 7HU - (01364) 653026 - www.barnowltrust.org.uk Reg Charity No: 299 835 One Man Went To Mow ! Our Own Wildlife Tower The Tale of the Tawny Trio and much, much more -1- FEEDBACK 44 - AUTUMN 2010 THE BARN OWL TRUST - CONSERVING THE BARN OWL AND ITS ENVIRONMENT Welcome to Feedback - It’s been another busy summer here at the Trust. In addition to our day-to-day work there have been lots of other things going on that you can read about in this issue. In this issue... This is the first issue since 1998 without Sandra Reardon on the editorial team so we’d like to take this opportunity to thank her for Welcome to Feedback 2 all her hard work over the years and to say we miss her. No doubt BOT News 3 she will “feedback” to us when we see her next month! More Barn Owl Trust News 4 Those of you that receive our annual report will have seen that One Man Went To Mow 5 we ended the last financial year with a surplus rather than the huge deficit we expected. This was due entirely to a significant In Memoriam 5 legacy which we have ring fenced for the meeting room, an insurance payout for the pond problems and grants LLP Update 6 and donations from charitable trusts. However, probably due to Bird News 7 the recession, donations from individuals dropped by 31% and we also saw a decline in our fundraising and sales income. -

Woodland Wonder: Tawny

Site Observer, county 04159 Mr Brown, Essex 01114 Joan Wilson, Ayrshire 04694 Mr Turner, East Sussex 04474 Mr Riley, East Sussex 05172 Brian Rodwell, Devon 04534 Ruth Barnes, Essex 02016 Michael Burkinshaw, North Yorks Woodland wonder: 03152 Mike Turner, Norfolk 07020 Ian Callan, Dyfed 01267 Donald Beaton, Sutherland 10104 Rex Knight, West Sussex Tawny Owl 03260 Kay Brandon, Lincolnshire 07102 Keith Jones, Gwent 04443 Marion Emberson, West Sussex 10064 Pat & Jim Clark, Anglesey Tawny Owl by Adrian Davies, naturepl.com hile the image of the squat, round- up against a tree trunk. Interestingly, there are headed Tawny Owl is likely to be some exceptional instances of Tawny Owls Wa familiar one, the chances are making use of open country, choosing to nest that you are more likely to have heard one in a quarry face or a disused farm building. this year than actually seen one. This, the Woodland Tawny Owls feed mainly on most common and widespread of our owls, is small mammals, notably Wood Mouse and also the most strongly nocturnal. A species of Bank Vole, but will also take other prey species deciduous and mixed woodland, the Tawny if they happen to be available. Amphibians, Owl may also be encountered in urban areas, bats and even fish have been recorded By Mike Toms where suitably-wooded parks or large gardens being taken by Tawny Owls. In urbanised Head of Garden Ecology may be used for breeding. landscapes, the owls seem to take more small birds, attacking roosting House Sparrows and WOODLAND LIFE Starlings. A few individual Tawny Owls have The association between the Tawny Owl and also been reported attacking House Martin woodland is something that was borne out by nests, breaking these mud nests open at night the BTO Tawny Owl Survey, carried out by to get at the chicks within. -

Measuring Owl Flight Noise

Measuring owl flight noise Thomas GEYER1; Ennes SARRADJ2; Christoph FRITZSCHE3 1;2 Chair for Technical Acoustics, BTU Cottbus - Senftenberg, Germany 3 now with the Thuringian State Institute for Environment and Geology, Germany ABSTRACT It is well known that most genera of owls are able to fly almost silently in order to hunt their prey. However, this knowledge is actually based on very few quantitative studies only. This is especially interesting regarding the fact that, against the background of increasing air traffic, the unique plumage adaptations of the owl responsible for the silent flight are the motivation behind various airframe noise reduction techniques such as serrations or porous trailing edges. Both by reviewing existing data and by means of appropriate experiments, the paper will first illustrate the special feather adaptations of owls and will expand upon their contribution to the silent flight. Then, following a brief review of existing measurement data on the silent owl flight from past studies, the paper will focus on more recent measurements of the noise generated by gliding owls. Thereby, two different approaches were followed: First, outdoor measurements of the noise emitted by gliding owls were performed using microphone array technology and a high speed camera setup to capture the flight path of the birds. Second, indoor measurements in an aeroacoustic open jet wind tunnel revealed the noise generated by prepared wings as well as their aerodynamic performance in terms of lift and drag forces. In both cases, special attention was paid to the difference between the flight noise of the owl compared to the noise of other, non-silently flying birds. -

DIET CHANGES in BREEDING TAWNY OWLS &Lpar;<I>Strix Aluco</I>&Rpar;

j Raptor Res. 26(4):239-242 ¸ 1992 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. DIET CHANGES IN BREEDING TAWNY OWLS (Strix aluco) DAVID A. KIRK 1 Departmentof Zoology,2 TillydroneAvenue, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen,Scotland, U.K. AB9 2TN ABSTVO,CT.--I examinedthe contentsof Tawny Owl (Strix alucosylvatica) pellets, between April 1977 and February 1978, in mixed woodlandand gardensin northeastSuffolk, England. Six mammal, 14 bird and 5 invertebratespecies were recordedin a sample of 105 pellets. Overall, the Wood Mouse (Apodemussylvaticus) was the most frequently taken mammal prey and the House Sparrow (Passer domesticus)was the mostfrequently identified bird prey. Two typesof seasonaldiet changewere found; first, a shift from mammal prey in winter to bird prey in the breedingseason, and second,a shift from smallprey in the winter to medium-sized(> 30 g) prey in the breedingseason. Contrary to somefindings elsewherein England, birds, rather than mammals, contributedsignificantly to Tawny Owl diet during the breedingseason. Cambiosen la dieta de bfihosde la especieStrix alucodurante el periodode reproduccibn EXTRACTO.--Heexaminado el contenidode egagrbpilasdel bfiho de la especieStrix alucosylvatica, entre abril de 1977 y febrerode 1978, en florestasy huertosdel norestede Suffolk, Inglaterra. Seismamlferos, catorceaves y cincoespecies invertebradas fueron registradosen una muestrade 105 egagrbpilas.En el total, entre los mamlferos,el roedorApodemus sylvaticus fue el que conmils frecuenciafue presade estos bfihos;y entre las aves,la presaidentificada con mils frecuenciafue el gorribnPasser domesticus. Dos tipos de cambib en la dieta estacionalfueron observados:primero, un cambib de clase de presa: de mamlferosen invierno a la de avesen la estacibnreproductora; y segundo,un cambiben el tamafio de las presas:de pequefiasen el inviernoa medianas(>30 g) en la estacibnreproductora. -

<I>STRIX ALUCO</I>

j Raptor Res. 28(4):246-252 ¸ 1994 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. DIET OF URBAN AND SUBURBAN TAWNY OWLS (STRIX ALUCO) IN THE BREEDING SEASON ANDRZEJ ZALEWSKI Mammal ResearchInstitute, Polish Academy of Sciences,77-230 Biatowieœa, Poland ABSTI•CT.--The diet of tawny owls (Strix aluco)was studiedduring the breedingseasons 1988-90 in an urbanand a suburbanarea in Torufi, Poland.Two amphibian,18 bird,and 14 mammalspecies were recordedas prey in a sampleof 312 pellets.From 600 prey itemsfound in bothsites, the housesparrow (Passerdomesticus) was the mostfrequently taken bird prey and the commonvole (Microtus arvalis) the mostfrequently taken mammal prey. Significantlymore mammals than birdswere taken at the suburban sitethan at the urbansite (P < 0.001). At the urbansite, the proportionof birds(except for tits [Parus spp.]and housesparrows) increased over the courseof the breedingseason, while the proportionof Apodemusspp. decreased.Similarly, at the suburbansite the proportionof all birds increasedand the proportionof Microtusspp. decreased. House sparrows at the urban site and Eurasiantree sparrows (Passermontanus) and tits at the suburbansite were takenin higherproportion than their availability. An examinationof dietarystudies from elsewhere in Europeindicated that therewas a positivecorrelation betweenmean prey sizeand increasingproportion of birdsin tawny owl diets(P = 0.003). KEY WORDS: tawnyowl; diet;urban and rural area;bird selection;prey-size selection. Dieta de Strixaluco urbano y suburbanoen la estaci6nreproductiva RESUMEN.--Seestudi6 la dietade Strixaluco durante las estacionesreproductivas de 1988 a 1990 en un fireaurbana y suburbanaen Torun, Polonia.Dos antibios, 18 avesy 14 especiesde mam•ferosfueron registradoscomo presa en una muestrade 312 egagr6pilas.De 600 categorlasde presasencontradas en ambossitios, Passer domesticus rue el ave-presamils frecuentejunto al mfimfferoMicrotus arvalis. -

Late Finishers and Early Starters

Bird Populations 8:168-170 Reprinted with permission BTO News 246:6-7 © British Trust for Ornithology 2003 LATE FINISHERS AND EARLY STARTERS DAVID GLUE British Trust for Ornithology The National Centre for Ornithology The Nunnery, Thetford Norfolk, IP24 2PU, United Kingdom BTO Research Biologist, David Glue, describes how a mild autumn and winter, led to late and early nesting activity among UK birds. TARDONES Y TEMPRANEROS El biólogo investigador del BTO David Glue describe cómo un otoño e invierno suaves han dado lugar a actividad de nidificación tardía y temprana en aves del Reino Unido. BTO volunteers charted a more productive though there were some surprises. The BTO breeding season for most resident and migrant Barn Owl Monitoring Programme showed that, species in 2002 compared with 2001. The early after a flying start in spring 2002, pairs were signs for 2003 are very hopeful. egg-laying a fortnight earlier than normal. About 10% of the monitored birds produced late clutches, with successes in November INDIAN SUMMER HELPS LATE (Lincs, Sussex and Notts) and even December NESTERS 2002, defying unfavourable hunting conditions. A pleasantly changeable midsummer mix of One unrivalled pair raised broods of four and weather in 2002 prolonged the breeding season nine young near Peterborough (Cambs). for many. Observations from nestbox Breeding activity was checked in mid monitoring revealed the latest ever free-flying December, as arctic air brought sharp frosts on broods of Little Owl, Great Tit and Pied 18–19th. Then over the Christmas week, Flycatcher, a result of repeat layings. The warm, unseasonably warm air lifted temperatures to a dry Indian summer heat in September saw balmy 15°C in sheltered South Devon and successful late breeding by a number of species. -

Alaja & Mikkola-33-37

Albinism in the Great Gray Owl (Strix nebulosa) and Other Owls Pentti Alaja and Heimo Mikkola1 Abstract.—An incomplete albino Great Gray Owl (Strix nebulosa) was observed in Vesanto and Kajaani, Finland, 1994-1995. The literature pertaining to albinism in owls indicates that total and incomplete albinism has only been reported in 13 different owl species, the Great Gray Owl being the only species with more than five records. Thus six to seven incomplete albino Great Grays have been recorded since 1980 in Canada, Finland, and the United States. ___________________ It would seem that most animals produce Partial albinism may result from injury, physio- occasional albinos; some species do so quite logical disorder, diet, or circulatory problems. frequently whilst this phenomenon is much This type of albinism is most frequently rarer in others. Although albinism in most observed. It is important to note that white avian families is frequently recorded, we know plumage is not necessarily proof of albinism. of very few abnormally white owls. Thus the motive of this paper is to assemble as complete Adult Snowy Owls (Nyctea scandiaca) are a record as possible of white or light color primarily white, but have their feather color mutations of owls which exist or have been derived from a schemochrome feather structure recorded. which possesses little or no pigment. Light reflects within the feather structure and GENETICS OF ALBINISM produces the white coloration (Holt et al. 1995). Albinism is derived from a recessive gene which ALBINISM IN THE GREAT GRAY OWLS inhibits the enzyme tyrosinase. Tyrosine, an amino acid, synthesizes the melanin that is the An extremely light and large Great Gray Owl basis of many avian colors (Holt et al. -

Food Niche Overlap of Avian Predators (Falconiformes, Strigiformes) in a Field and Forest Mosaic in Central Poland

animals Article Food Niche Overlap of Avian Predators (Falconiformes, Strigiformes) in a Field and Forest Mosaic in Central Poland Jakub Gryz 1,* and Dagny Krauze-Gryz 2 1 Department of Forest Ecology, Forest Research Institute, S˛ekocin Stary, Braci Le´snej3, 05-090 Raszyn, Poland 2 Department of Forest Zoology and Wildlife Management, Institute of Forest Sciences, Warsaw University of Life Sciences, Nowoursynowska 159, 02-776 Warszawa, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-22-7150-419 Simple Summary: Predators may present various feeding strategies, i.e., being either food specialists or opportunists. At the same time, their diets change to reflect the prey availability and to avoid competition for food resources. We performed this research in a highly transformed field and forest mosaic and in an area with a high abundance of avian predators (owls and birds of prey, ~133 breeding pairs in total). We calculated the food niche overlap statistics to show the competition for food resources between coexisting species. We assessed the diet composition on the basis of pellet analyses and the identification of prey remains collected from under nests during the breeding season. The food niches overlapped moderately with only one exception, i.e., the highest niche overlap was recorded for the common buzzard and common kestrel, two species preying in open spaces on field rodents but switching to soricomorphs when the former were scarce. On the contrary, the most separate food niche was that of the white-tailed eagle, which was the only species regularly preying on fish. Our results showed that the food niches of species coexisting in the same area were considerably separate, which is due to the fact that they prey on various prey species or search for them in different habitats. -

Factors Influencing the Size of Some Internal Organs in Raptors

j RaptorRes. 30(4):219-223 ¸ 1996 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. FACTORS INFLUENCING THE SIZE OF SOME INTERNAL ORGANS IN RAPTORS NIGEL W. BARTON AND DAVID C. HOUSTON AppliedOrnithology Unit, Divisionof Evolutionaryand EnvironmentalBiology, Graham Kerr Building, Universityof Glasgow,Glasgow, G12 8Q• Scotland ABSTP•CT.--Thesize of the small intestine, stomach, kidney, liver and heart were compared among raptor speciesand considered in relation to hunting strategyand body size. Speciesrelying on rapid accelerationand maneuverabilityto captureprey in flight, suchas sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus), goshawk (A. gentilis),and peregrine (Falcoperegrinus), had the smallestdigestive tracts for their size. Species depending more on soaringflight which do not need fast accelerationto capture prey,such as common buzzard (Buteobuteo), red kite (Milvus milvus), and European kestrel (Falco tinnunculus),had heavy digestiveorgans. In the Strigiformes,the same relationship wasfound, and specieswhich hunt by active flight, such as barn owl (Tyt0 alba), and 1ong-earedowl (Asio otus),had significantlylighter digestive tracts than the tawny owl (Strix aluco),a specieswhich mainly hunts from a perch dropping onto its prey from above.Body condition waspositively correlated with organ weights,including the heart, but to a lesserextent with linear measuresof size such as intestine length. KEYWOe. DS: internalorgans; predatory birds; condition. Factoresque infiuencian el tamafio de algunos6rganos internos en rapaces RESUMEN.--EItamafio del intestinodelgado, est6mago, -

Tawny Owl Females of Intermediate Colour Morph Reproduce Better and Increase in a Local Polymorphic Population

Ornis Fennica 94: 33–44. 2017 Tawny Owl females of intermediate colour morph reproduce better and increase in a local polymorphic population Gintarë Graytë, Saulius Rumbutis, Mindaugas Dagys, Daiva Vaitkuvienë & Rimgaudas Treinys* Graytë, G., Dagys, M., Vaitkuvienë, D., Treinys, R., Nature Research Centre, Akademi- jos str. 2, 08412 Vilnius, Lithuania. * Corresponding authors e-mail: rimga.t@gmail. com Rumbutis, S., T. Ivanauskas Zoological Museum, Laisvës ave. 106, 44253 Kaunas, Lithu- ania Received 31 August 2016, accepted 15 January 2017 Individuals of the same population with differing melanin plumage colouration can re- spond differently through fitness to environmental stressors. In a local population of Tawny Owls (Strix aluco), we collected individual-based data on nesting attempts of this well-known colour polymorphic species between 1985 and 2014. We studied whether body size, condition, demographic parameters and habitat around occupied nest sites dif- fer among grey, intermediate and brown coloured females. The proportions of females belonging to each of the three colour morphs in the local population changed during the study period, withintermediate individua ls becoming more frequent in the last decade. Females were similar in body size and achieved similar body condition during breeding irrespective of plumage colouration. Although most of the analysed demographic param- eters were not statistically significantly related to the colour morph, the intermediate owls raised more nestlings in a lifetime and tended to have higher recapture probability. We found little support for habitat and morph associations. In summary, we propose that the increase in intermediate Tawny Owl colour morphs in this local population is associated with their better reproductive performance compared to the other morphs. -

Austria and Hungary Birding Adventure

1 | ITINERARY Austria and Hungary Birding Adventure AUSTRIA AND HUNGARY BIRDING ADVENTURE 12 – 23 MAY 2021 Eurasian Bittern will hopefully be found on this trip. 2 | ITINERARY Austria and Hungary Birding Adventure This tour takes us through two great birding destinations at the heart of Europe, Austria and Hungary. The itinerary comprises uplands in Austria in the Alps and lowlands in the Hungarian plains. Our route takes us through many key Central European habitats and will allow us to observe a large number of bird species of this area, which include many species that rarely occur in the west of Europe. These include Pygmy Cormorant, Ferruginous Duck, Saker Falcon, Eastern Imperial Eagle, Syrian and White-backed Woodpeckers (among ten woodpecker species, for which, with luck, we have a fair chance to see them all), and River and Barred Warblers. Around 200 bird species can be expected. White-backed Woodpecker is one of the ten species of woodpeckers we may see on this tour. In addition, both countries have rich histories, with some impressive architecture, which will be apparent as we travel through and explore them. We will spend the nights in smaller guest houses in the best birding locations, rather than in big hotels in towns. All rooms are en-suite and the cuisine and wines are local. Itinerary (12 days/11 nights) Day 1. Arrival in Vienna, two-hour transfer to the Lower Alps (Austria) We will meet at the Vienna International Airport at noon and then depart south-westward for the forested mountains of Niederösterreich (Lower Austria), a journey of less than two hours. -

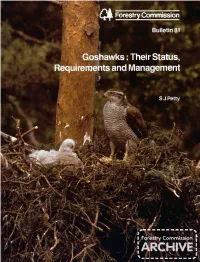

Goshawks: Their Status Requirements and Management

Forestry Commission Bulletin 81 Goshawks: Their Status Requirements and Management Forestry Commission ARCHIVE Forestry Commission Bulletin 81 Goshawks: Their Status, Requirements and Management S. J. Petty Wildlife and Conservation Research Branch, Forestry Commission LONDON: HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE © Crown copyright 1989 First published 1989 ISBN 0 11 710269 5 ODC 148.2:151:156:(410) Keywords: Birds, Forestry Enquiries relating to this publication should be addressed to the Technical Publications Officer, Forestry Commission, Forest Research Station, Alice Holt Lodge, Wrecclesham, Farnham, Surrey GU10 4LH FRONT COVER: Female goshawk at a nest with downy chicks. The large nest has been built on a substantial whorl of branches in a Scots pine. (G. Lind) Contents Page Introduction 5 Description 5 Status 5 Food 6 Habitat requirements 7 Population density and productivity 13 Protection 13 The management of nesting areas 14 Locating nesting areas 14 Retaining nesting areas 14 Protecting nest trees and the use of artificial platforms 15 Controlling disturbance 16 Accidents and robberies 16 Acknowledgements 16 References 17 Goshawks: Their Status, Requirements and Management S. J. Petty Bird Ecologist, Forestry Commission Introduction earlier, probably as a result of the extensive defores tation which occurred in lowland Britain and some The goshawk is a large bird of prey which was parts of the uplands prior to the 16th century re-introduced into Britain in the 1960s and 1970s.(Dimbleby, 1984). Populations are now beginning to expand, particularlyThe goshawk occurs in boreal and temperate zones in areas with large forests, and where human perseof the northern hemisphere and is relatively common in cution is not a limiting factor.