Barber Violin Concerto, Op. 14 Sh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

String Quartet in E Minor, Op 83

String Quartet in E minor, op 83 A quartet in three movements for two violins, viola and cello: 1 - Allegro moderato; 2 - Piacevole (poco andante); 3 - Allegro molto. Approximate Length: 30 minutes First Performance: Date: 21 May 1919 Venue: Wigmore Hall, London Performed by: Albert Sammons, W H Reed - violins; Raymond Jeremy - viola; Felix Salmond - cello Dedicated to: The Brodsky Quartet Elgar composed two part-quartets in 1878 and a complete one in 1887 but these were set aside and/or destroyed. Years later, the violinist Adolf Brodsky had been urging Elgar to compose a string quartet since 1900 when, as leader of the Hallé Orchestra, he performed several of Elgar's works. Consequently, Elgar first set about composing a String Quartet in 1907 after enjoying a concert in Malvern by the Brodsky Quartet. However, he put it aside when he embarked with determination on his long-delayed First Symphony. It appears that the composer subsequently used themes intended for this earlier quartet in other works, including the symphony. When he eventually returned to the genre, it was to compose an entirely fresh work. It was after enjoying an evening of chamber music in London with Billy Reed’s quartet, just before entering hospital for a tonsillitis operation, that Elgar decided on writing the quartet, and he began it whilst convalescing, completing the first movement by the end of March 1918. He composed that first movement at his home, Severn House, in Hampstead, depressed by the war news and debilitated from his operation. By May, he could move to the peaceful surroundings of Brinkwells, the country cottage that Lady Elgar had found for them in the depth of the Sussex countryside. -

Thursday Playlist

February 20, 2020: (Full-page version) Close Window “Lesser artists borrow, great artists steal.” — Igor Stravinsky Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No. 6 in D Budapest Festival Orchestra/Fischer Philips 456 570 028945657028 Awake! Symphony in D, "The Petrification of Phineus and 00:13 Buy Now! Dittersdorf Cantilena/Shepherd Chandos 8564/5 5014682856423 his Friends" 00:31 Buy Now! Haydn Symphony No. 076 in E flat Academy of Ancient Music/Hogwood BBC MM253 n/a Vonsattel/Sussmann/Swensen/O'Neill 01:01 Buy Now! Franck Piano Quintet in F minor Music@Menlo Live n/a 653738268220 /Finckel New York Chamber Music 01:35 Buy Now! Lully Suite ~ The Forced Marriage Dorian 90189 053479018922 Ensemble/Pederson 01:45 Buy Now! Mozart Fantasia in C minor, K. 475 Lars Vogt EMI 36080 094633608023 02:00 Buy Now! Weber Overture ~ Der Freischutz Philharmonia/Klemperer EMI 13073 n/a 02:11 Buy Now! Strauss, R. 2nd mvt (Andante) ~ Cello Sonata in F, Op. 6 Coppey/le Sage Harmonia Mundi 911550 794881314324 02:20 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3 in A minor, Op. 56 "Scottish" London Classical Players/Norrington EMI 54000 077775400021 Rimsky- 02:59 Buy Now! Ivan the Terrible National Philharmonic/Stokowski Sony Classical 62647 074646264720 Korsakov 03:04 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky The Seasons (orchestrated version) Moscow Chamber Orchestra/Orbelian Delos 3255 013491325521 03:48 Buy Now! Handel Concerto Grosso in G, Op. 6 No. 1 Guildhall String Ensemble/Salter RCA 7895 078635789522 04:01 Buy Now! Devienne Flute Concerto No. -

Tertis's Viola Version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to Clevelandclassical

Preview Heights Chamber Orchestra conductor's notes: Tertis's viola version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to ClevelandClassical An old adage suggested that violists were merely vio- linists-in-decline. That was before Lionel Tertis! He was born in 1876 of musical parents who had come to England from Poland and Russia and, at three years old, he started playing the piano. At six he performed in public, but had to be locked in a room to make him practice, a procedure that has actually fostered many an international virtuoso. At thirteen, with the agree- ment of his parents, he left home to earn his living in music playing in pickup groups at summer resorts, accompanying a violinist, and acting as music attendant at a lunatic asylum. +41:J:-:/1?<1>95@@1041?@A0510-@(>5:5@E;88131;2!A?5/@-75:3B5;85:-?45? "second study," but concentrating on the piano and playing concertos with the school or- chestra. As sometime happens, his violin teacher showed little interest in a second study <A<58-:01B1:@;8045?2-@41>@4-@41C-?.1@@1>J@@102;>@413>;/1>E@>-01 +5@4?A/4 encouragement, Tertis decided he had to teach himself. Fate intervened when fellow stu- dents wanted to form a string quartet. Tertis volunteered to play viola, borrowed an in- strument, loved the rich quality of its lowest string and thereafter turned the old adage up- side down: a not very obviously gifted violinist becoming a world class violist. But, until the viola attained respectability in Tertis’s hands, composers were reluctant to write for the instrument. -

Barber Piano Sonata in E-Flat Minor, Opus 26

Barber Piano Sonata In E-flat Minor, Opus 26 Comparative Survey: 29 performances evaluated, September 2014 Samuel Barber (1910 - 1981) is most famous for his Adagio for Strings which achieved iconic status when it was played at F.D.R’s funeral procession and at subsequent solemn occasions of state. But he also wrote many wonderful songs, a symphony, a dramatic Sonata for Cello and Piano, and much more. He also contributed one of the most important 20th Century works written for the piano: The Piano Sonata, Op. 26. Written between 1947 and 1949, Barber’s Sonata vies, in terms of popularity, with Copland’s Piano Variations as one of the most frequently programmed and recorded works by an American composer. Despite snide remarks from Barber’s terminally insular academic contemporaries, the Sonata has been well received by audiences ever since its first flamboyant premier by Vladimir Horowitz. Barber’s unique brand of mid-20th Century post-romantic modernism is in full creative flower here with four well-contrasted movements that offer a full range of textures and techniques. Each of the strongly characterized movements offers a corresponding range of moods from jagged defiance, wistful nostalgia and dark despondency, to self-generating optimism, all of which is generously wrapped with Barber’s own soaring lyricism. The first movement, Allegro energico, is tough and angular, the most ‘modern’ of the movements in terms of aggressive dissonance. Yet it is not unremittingly pugilistic, for Barber provides the listener with alternating sections of dreamy introspection and moments of expansive optimism. The opening theme is stern and severe with jagged and dotted rhythms that give a sense of propelling physicality of gesture and a mood of angry defiance. -

Solving Elgar's Enigma

Solving Elgar's Enigma Charles Richard Santa and Matthew Santa On June 19, 1899, Elgar's opus 36, Variations on a Theme, was introduced to the public for the first time. It was accompanied by an unusual program note: It is true that I have sketched for their amusement and mine, the idiosyn crasies of fourteen of my friends, not necessarily musicians; but this is a personal matter, and need not have been mentioned publicly. The Varia tions should stand simply as a "piece" of music. The Enigma I will not explain-its "dark saying" must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the connexion between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole set [of variations 1 another and larger theme "goes" but is not played ... So the principal Theme never appears, even as in some late dramas-e.g., Maeterlinck's "L'Intruse" and "Les sept Princesses" -the chief character is never on the stage. (Burley and Carruthers 1972:119) After this premier Elgar give hints about the piece's "Enigma;' but he never gave the solution outright and took the secret to his grave. Since that time scholars, music lovers, and cryptologists have been trying to solve the Enigma. Because the solution has not been discovered in spite of over 108 years of searching, many people have assumed that it would never be found. In fact, some have speculated that there is no solution, and that the promise of an Enigma was Elgar's rather shrewd way of garnering publicity for the piece. -

AUGUST JAEGER: PORTRAIT of NIMROD Frontispiece Visiting the Sick

AUGUST JAEGER: PORTRAIT OF NIMROD Frontispiece Visiting the sick. Lady Olga Wood and Professor Sanford take their leave of Jaeger and the children outside 37 Curzon Road, Muswell Hill, c. 1905. August Jaeger: Portrait of Nimrod A Life in Letters and Other Writings KEVIN ALLEN First published 2000 by Ashgate Publishing Reissued 2018 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © Kevin Allen, 2000 The author has asserted his moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Publisher s Note The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. Disclaimer The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact. A Library of Congress record exists under LC control number: 00023684 Typeset in Garamond by The Midlands Book Typesetting Company, Loughborough, Leics. ISBN 13: 978-1-138-73208-7 (hbk) ISBN 13: 978-1-315-18862-1 (ebk) Contents list of Plates vii Foreword by Percy M. -

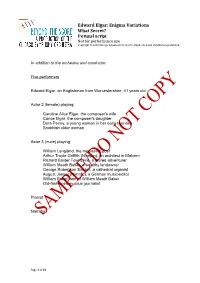

Edward Elgar: Enigma Variations What Secret? Perusal Script Not for Performance Use Copyright © 2010 Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Edward Elgar: Enigma Variations What Secret? Perusal script Not for performance use Copyright © 2010 Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Duplication and distribution prohibited. In addition to the orchestra and conductor: Five performers Edward Elgar, an Englishman from Worcestershire, 41 years old Actor 2 (female) playing: Caroline Alice Elgar, the composer's wife Carice Elgar, the composer's daughter Dora Penny, a young woman in her early twenties Snobbish older woman Actor 3 (male) playing: William Langland, the mediaeval poet Arthur Troyte Griffith (Ninepin), an architect in Malvern Richard Baxter Townsend, a retired adventurer William Meath Baker, a wealthy landowner George Robertson Sinclair, a cathedral organist August Jaeger (Nimrod), a German music-editor William Baker, son of William Meath Baker Old-fashioned musical journalist Pianist Narrator Page 1 of 21 ME 1 Orchestra, theme, from opening to figure 1 48" VO 1 Embedded Audio 1: distant birdsong NARRATOR The Malvern Hills... A nine-mile ridge of rock in the far west of England standing about a thousand feet above the surrounding countryside... From up here on a clear day you can see far into the distance... on one side... across the patchwork fields of Herefordshire to Wales and the Black Mountains... on another... over the river Severn... Shakespeare's beloved river Avon... and the Vale of Evesham... to the Cotswolds... Page 2 of 21 and... if you're lucky... to the north, you can just make out the ancient city of Worcesteri... and the tall square tower of its cathedral... in the shadow of which... Edward Elgar spent his childhood and his youth.. -

A Formal Analytical Approach Was Utilized to Develop Chart Analyses Of

^ DOCUMENT RESUME ED 026 970 24 HE 000 764 .By-Hanson, John R. Form in Selected Twentieth-Century Piano Concertos. Final Report. Carroll Coll., Waukesha, Wis. Spons Agency-Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. Bureauof Research. Bureau No-BR-7-E-157 Pub Date Nov 68 Crant OEC -0 -8 -000157-1803(010) Note-60p. EDRS Price tvw-s,ctso HC-$3.10 Descriptors-Charts, Educational Facilities, *Higher Education, *Music,*Music Techniques, Research A formal analytical approach was utilized to developchart analyses of all movements within 33 selected piano concertoscomposed in the twentieth century. The macroform, or overall structure, of each movement wasdetermined by the initial statement, frequency of use, andorder of each main thematic elementidentified. Theme groupings were then classified underformal classical prototypes of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (ternary,sonata-allegro, 5-part or 7-part rondo, theme and variations, and others), modified versionsof these forms (three-part design), or a variety of free sectionalforms. The chart and thematic illustrations are followed by a commentary discussing each movement aswell as the entire concerto. No correlation exists between styles andforms of the 33 concertos--the 26 composers usetraditional,individualistic,classical,and dissonant formsina combination of ways. Almost all works contain commonunifying thematic elements, and cyclicism (identical theme occurring in more than1 movement) is used to a great degree. None of the movements in sonata-allegroform contain double expositions, but 22 concertos have 3 movements, and21 have cadenzas, suggesting that the composers havelargely respected standards established in theClassical-Romantic period. Appendix A is the complete form diagramof Samuel Barber's Piano Concerto, Appendix B has concentrated analyses of all the concertos,and Appendix C lists each movement accordog to its design.(WM) DE:802 FINAL REPORT Project No. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op

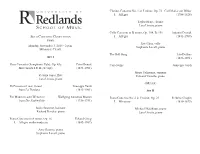

Clarinet Concerto No. 1 in F minor, Op. 73 Carl Maria von Weber I. Allegro (1786-1826) Taylor Heap, clarinet Lara Urrutia, piano Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104, B. 191 Antonin Dvorák SOLO CONCERTO COMPETITION I. Allegro (1841-1904) Finals Xue Chen, cello Monday, November 3, 2014 - 2 p.m. Stephanie Lovell, piano MEMORIAL CHAPEL The Bell Song Léo Delibes SET I (1836-1891) Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op. 43a Peter Benoit Caro Nome Guiseppe Verdi Movements I & II (excerpt) (1834-1901) Mayu Uchiyama, soprano Victoria Jones, flute Edward Yarnelle, piano Lara Urrutia, piano - BREAK - Di Provenza il mar, il suol Giuseppe Verdi from La Traviata (1813-1901) SET II Ein Madehen oder Weibchen Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 Frédéric Chopin from Die Zauberflöte (1756-1791) I. Maestoso (1810-1849) Justin Brunette, baritone Michael Malakouti, piano Richard Bentley, piano Lara Urrutia, piano Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 Edvard Grieg I. Allegro molto moderato (1843-1907) Amy Rooney, piano Stephanie Lovell, piano Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle Charles Gounod ABOUT THE CONCERTO COMPETITION from Roméo et Juliette (1818-1893) Beginning in 1976, the Concerto Competition has become an annual event Cruda Sorte Gioacchino Rossini for the University of Redlands School of Music and its students. Music from L’Ataliana in Algeri (1792-1868) students compete for the coveted prize of performing as soloist with the Redlands Symphony Orchestra, the University Orchestra or the Wind Jordan Otis, soprano Ensemble. Twyla Meyer, piano This year the Preliminary Rounds of the Competition took place on Friday, October 31st and Saturday, November 1st. -

The Elgar Sketch-Books

THE ELGAR SKETCH-BOOKS PAMELA WILLETTS A MAJOR gift from Mrs H. S. Wohlfeld of sketch-books and other manuscripts of Sir Edward Elgar was received by the British Library in 1984. The sketch-books consist of five early books dating from 1878 to 1882, a small book from the late 1880s, a series of eight volumes made to Elgar's instructions in 1901, and two later books commenced in Italy in 1909.^ The collection is now numbered Add. MSS. 63146-63166 (see Appendix). The five early sketch-books are oblong books in brown paper covers. They were apparently home-made from double sheets of music-paper, probably obtained from the stock of the Elgar shop at 10 High Street, Worcester. The paper was sewn together by whatever means was at hand; volume III is held together by a gut violin string. The covers were made by the expedient of sticking brown paper of varying shades and textures to the first and last leaves of music-paper and over the spine. Book V is of slightly smaller oblong format and the sides of the music sheets in this volume have been inexpertly trimmed. The volumes bear Elgar's numbering T to 'V on the covers, his signature, and a date, perhaps that ofthe first entry in the volumes. The respective dates are: 21 May 1878(1), 13 August 1878 (II), I October 1878 (III), 7 April 1879 (IV), and i September 1881 (V). Elgar was not quite twenty-one when the first of these books was dated. Earlier music manuscripts from his hand have survived but the particular interest of these early sketch- books is in their intimate connection with the round of Elgar's musical activities, amateur and professional, at a formative stage in his career. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No.