Florida Medicaid Pharmacy Claims Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overview of Ftc Antitrust Actions in Pharmaceutical Services and Products

OVERVIEW OF FTC ANTITRUST ACTIONS IN PHARMACEUTICAL SERVICES AND PRODUCTS Health Care Division Bureau of Competition Federal Trade Commission Washington D.C. 20580 Markus H. Meier Assistant Director Bradley S. Albert Deputy Assistant Director Saralisa C. Brau Deputy Assistant Director September 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION. ........................................................... 1 II. CONDUCT INVOLVING PHARMACEUTICAL SERVICES AND PRODUCTS. 3 A. Monopolization. ...................................................... 3 B. Agreements Not to Compete. ............................................ 8 C. Agreements on Price or Price-Related Terms. 14 D. Agreements to Obstruct Innovative Forms of Health Care Delivery or Financing. 20 E. Illegal Tying and Other Arrangements. .................................... 20 III. PHARMACEUTICAL MERGERS. ........................................... 20 A. Horizontal Mergers Between Direct Competitors. 20 B. Potential Competition Mergers. ......................................... 44 C. Innovation Market Mergers. ............................................ 47 D. Vertical Mergers...................................................... 49 IV. INDUSTRY GUIDANCE STATEMENTS...................................... 50 A. Advisory Opinions. ................................................... 50 B. Citizen Petition to the Food and Drug Administration. 51 V. AMICUS BRIEFS. ......................................................... 51 VI. INDICES. ............................................................ -

PRECEDENTIAL UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS for the THIRD CIRCUIT ___Nos. 14-4202, 14-4203, 14-4204, 14-4205, 14-4206, 14-46

Case: 14-4203 Document: 003112598145 Page: 1 Date Filed: 04/19/2017 PRECEDENTIAL UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT ______ Nos. 14-4202, 14-4203, 14-4204, 14-4205, 14-4206, 14-4602 & 14-4632 ______ IN RE: LIPITOR ANTITRUST LITIGATION Rite Aid Corporation; Rite Aid Hdqtrs. Corporation; JC (PJC) USA, LLC; Maxi Drug, Inc. d/b/a Brooks Pharmacy; Eckerd Corporation, Appellants in No. 14-4202 Walgreen Company; The Kroger Co.; Safeway, Inc.; Supervalu, Inc.; HEB Grocery Company L.P., Appellants in No. 14-4203 Giant Eagle, Inc., Appellant in No. 14-4204 Meijer, Inc.; Meijer Distribution, Inc., Appellants in No. 14-4205 Rochester Drug Co-Operative, Inc.; Stephen L. LaFrance Pharmacy, Inc. d/b/a SAJ Distributors; Burlington Drug Company, Inc.; Value Drug Company; Professional Drug Company, Inc.; American Sales Company LLC, Appellants in No. 14-4206 Case: 14-4203 Document: 003112598145 Page: 2 Date Filed: 04/19/2017 A.F.L.-A.G.C. Building Trades Welfare Plan; Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, Maryland; New Mexico United Food and Commercial Workers Union’s and Employers’ Health and Welfare Trust Fund; Louisiana Health Service Indemnity Company, d/b/a Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Louisiana; Bakers Local 433 Health Fund; Twin Cities Bakery Workers Health and Welfare Fund; Fraternal Order of Police, Fort Lauderdale Lodge 31, Insurance Trust Fund; International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 98; New York Hotel Trades Counsel & Hotel Association of New York City, Inc., Health Benefits Fund; Edward Czarnecki; Emilie Heinle; Frank Palter; Andrew Livezey; Edward Ellenson; Jean Ellyne Dougan; Nancy Billington, on behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated, Appellants in No. -

CVS Corporation 2004 Annual Report H Cvrs Narrative 3/17/05 12:18 PM Page +6

h_cvrs_narrative 3/17/05 12:17 PM Page +3 At CVS, it’s all in a day’s work... CVS Corporation 2004 Annual Report h_cvrs_narrative 3/17/05 12:18 PM Page +6 2:00am Another customer finds relief. From a toddler’s ear infection to a flare up of asthma, illnesses often have little regard for the clock. CVS has been doing its part to help, with approximately 60 percent of our stores offering 24- or extended- hour service. It’s just one of the many ways we make our pharmacy experience “CVS easy.”™ After all, the pharmacy accounts for 70 percent of our overall sales. CVS has a 13.5 percent share of the retail pharmacy market nationally, and we fill one in every five prescriptions in markets where we operate. Thanks to the Pharmacy Service Initiative (PSI) we launched in 2003, CVS is also making sure that prescriptions are “ready when promised”™ at any hour. Our pharmacy initiatives have freed up our pharmacists to spend more time counseling customers as well. As a result, customer service scores posted healthy gains in 2004. To realize similar benefits in the acquired Eckerd stores, we completed the training of more than 11,000 pharmacists and pharmacy support personnel on CVS systems, service processes, and standards. With more than 5,300 retail stores throughout the country and more on the way, CVS is well positioned to benefit from long-term pharmacy growth trends. The U.S. population is aging, healthcare costs are rising, and pharmaceuticals remain often the most cost-effective form of treatment. -

Petitoner's Jurisdictional Brief

IN THE FLORIDA SUPREME COURT S. Ct. Case No.: CASE NO.: 3D05-2253 GARRETT DENT, Petitioner/Plaintiff, vs. DENNIS PHARMACY, INC., Respondent/Defendant. __________________________/ PETITONER’S JURISDICTIONAL BRIEF Respectfully submitted, David S. Wieder, Esq. Fla. Bar No.:153129 David S. Wieder, P.A. Hermelee & Geffin, LLC Counsel for Garrett Dent 25 S.E. 2nd Ave., Suite 1135 Miami, Florida 33131 Telephone: (305) 373-5444 Facsimile: (305) 373-0039 & David Hagen, Esq. Fla. Bar No.: 158143 49 E. Flagler St., PH104 Miami, Florida 33131 Telephone:(305) 373-4200 Facsimile: (305) 403-4900 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES iii OTHER AUTHORITIES iv STATEMENT OF THE CASE AND FACTS 1 STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION 2 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT 3 ARGUMENT 4 THE DISTRICT COURTS ARE IN DIRECT CONFLICT REGARDING WHETHER A PHARMACIST HAS A DUTY TO WARN CUSTOMERS OF DANGERS ASSOCIATED WITH A PRESCRIPTION DRUG. 4 THE DISTRICT COURTS ARE IN DIRECT CONFLICT REGARDING WHETHER RELIANCE IS A NECESSARY ELEMENT OF A VOLUNTARY UNDERTAKING CAUSE OF ACTION. 7 THE DISTRICT COURTS ARE IN DIRECT CONFLICT REGARDING WHETHER AN UNIDENTIFIED THIRD PARTY CAN FALL WITHIN A REASONABLE AND FORESEEABLE ZONE OF RISK. 8 THE THIRD DISTRICT COURT EXPRESSLY DECLARED VALID FLA. STAT. §465.003 AND FLA. ADMIN. CODE R. 64B16-27.820. 10 CONCLUSION 10 CERTIFICATE OF TYPE SIZE AND STYLE 11 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE 12 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Arab Termite and Pest Control v. Jenkins, 409 So. 2d 1039 (Fla. 1982). 2 Cheeks v. Dorsey, 846 So. 2d 1169 (Fla. 4th DCA 2003). 9 Clay Electric v. -

Revised January 21, 2016

RITE AID CORPORATION DISTRIBUTION CENTERS / SHIP–TO-LOCATIONS ENTITY REFERENCE DC SHIP-TO-LOCATIONS / PO DEA NUMBER DUNS NO.+ 4 PREFERRED LTL CARRIER CHARLOTTE DISTRIBUTION CENTER 1776 Statesville Avenue YRC, ESTES, UPS Eckerd Corporation N/A 0145788920053 Charlotte, NC 28206 (704) 371-3653 DAYVILLE DISTRIBUTION CENTER Killingly Oaks Business Park YRC, ESTES, UPS, PJC Distributions Inc 500 Forbes Road N/A 0145788920054 NEW ENGLAND MOTOR Dayville, CT 06241 FREIGHT (860) 779-0632 LIVERPOOL DISTRIBUTION CENTER* YRC, ESTES, UPS, 7245 Henry Clay Boulevard Eckerd Corporation RE0356003 0145788920055 NEW ENGLAND MOTOR Liverpool, NY 13088 FREIGHT (315) 451-5700 x2274 PHILADELPHIA DISTRIBUTION CENTER YRC, ESTES, UPS, 1 Geoffrey Road Thrift Drug Inc N/A 0145788920056 NEW ENGLAND MOTOR Fairless Hills, PA 19030 FREIGHT (215) 428-5917 PERRYMAN DISTRIBUTION CENTER* YRC, ESTES, UPS, 601 Chelsea Road Rite Aid of Maryland Inc RR0236073 0145788920010 NEW ENGLAND MOTOR Aberdeen MD 21001-4306 FREIGHT (410) 297-6363 RITE AID FIXTURE DISTRIBUTION CENTER 325 Welltown Road N/A YRC, ESTES, UPS N/A 0145788920023 Winchester, VA 22603 (540) 662-3552 PONTIAC DISTRIBUTION CENTER* 5400 Perry Drive YRC, ESTES, UPS Perry Drug Stores 002230PIY 0145788920029 Waterford, MI 48329 (248) 674-7770 TUSCALOOSA DISTIBUTION CENTER* 3931 Rice Mine Road NE YRC, ESTES, UPS HARCO Inc RH0231124 0145788920035 Tuscaloosa, AL 35406 (205) 345-7419 x225 POCA DISTRIBUTION CENTER* 160 Jacobson Drive YRC, ESTES, UPS Rite Aid of West Virginia Inc 004569RDY 0145788920050 Poca WV 25159-9772 (304) -

Leveraged Buy out of Revco D S Inc

2012 Leveraged Buy Out of Revco D S Inc. Group - 4 Department of Finance, University of Dhaka 9/9/2012 Leverage Buyout of Revco D S Inc Submitted To: Dr. Md. Sadiqul Islam Professor Department of Finance University of Dhaka Submitted By: Group no. 4 13th batch Department of Finance University of Dhaka Date of Submission: 09 September, 2012 Group Members Name Roll Mohammed Robiul Alam 13-643 ASM Zakariya 13-578 Rokeya Mahzavin 13-588 Md. Shah Naoaj 13-686 Taslima Akter 13-666 Letter of Transmittal Dr. Md. Sadiqul Islam Professor Department of Finance University Of Dhaka Subject: Submission of Case Report. Dear Sir: With great pleasure and honor we are submitting our case report on ―Leverage Buy Out of Revco D S Inc‖. The case study includes analysis of LBO of Revco. We analyzed the LBO from different viewpoints by using various financial tools and software. We have tried our best to accommodate as much information and relevant issues as possible and follow the instructions that you have given. We would like to thank you for providing us with the opportunity to prepare this case report. Sincerely Yours Group -04 13th batch Department of Finance University of Dhaka Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. The Company ........................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2. Competition .......................................................................................................................................... -

Platte City, Missouri (Kansas City MSA)

Platte City, Missouri (Kansas City MSA) Offering Memorandum Presented by the Patton | Wiles | Fuller Group of Marcus & Millichap Platte City, Missouri (Kansas City MSA) Exclusively Listed by the Patton / Wiles / Fuller Group of Marcus & Millichap: Dustin Javitch Craig Fuller First Vice President Investments Senior Managing Director Net Leased Properties Group National Retail Group Cleveland Office Cleveland Office P: (216) 264-2025 P: (216) 264-2043 [email protected] [email protected] License: OH SAL.2012000193 License: OH SAL.2008001551 Scott Wiles Erin Patton Senior Managing Director Senior Managing Director National Retail Group National Retail Group Cleveland Office Columbus Office P: (216) 264-2026 P: (614) 360-9035 [email protected] [email protected] License: OH SAL.2005013197 License: OH SAL.2004010274 Absolute Net Lease CVS with 14.25 Years Remaining Located in the Kansas City MSA 20-MI Demographics 1301 Platte Falls Road 512,683 Platte City, MO (Kansas City MSA) 64079 Total Population Investment Highlights Location Highlights $85,217 • Absolute Net Lease CVS with 14.25 Years • Affluent Kansas City Suburb | Average Average Household Income Remaining Located in the Kansas City MSA Household Income $108,200 Within a 5-Mile Radius • 2020 Remodel to the New HealthHUB Concept | ~$450,000 in Tenant Paid • Positioned Along Area’s Major Retail & Improvements Traffic Corridor | Easy Access & Excellent Visibility 1.5% • Rare Rental Increases in Renewal Options | 15% in Option 1 -

Revised December 6, 2018

RITE AID CORPORATION DISTRIBUTION CENTERS / SHIP–TO-LOCATIONS ENTITY REFERENCE DC SHIP-TO-LOCATIONS / PO DEA NUMBER DUNS NO.+ 4 PREFERRED LTL CARRIER LIVERPOOL DISTRIBUTION CENTER* 7245 Henry Clay Boulevard YRC, NEMF, FEDEX, ESTES, Eckerd Corporation RE0356003 0145788920055 Liverpool, NY 13088 FREIGHT, OLD DOMINION (315) 451-5700 x2274 PHILADELPHIA DISTRIBUTION CENTER 1 Geoffrey Road YRC, NEMF, FEDEX, ESTES, , Thrift Drug Inc N/A 0145788920056 Fairless Hills, PA 19030 OLD DOMINION (215) 428-5917 PERRYMAN DISTRIBUTION CENTER* 601 Chelsea Road YRC, NEMF, FEDEX, ESTES, Rite Aid of Maryland Inc RR0236073 0145788920010 Aberdeen MD 21001-4306 OLD DOMINION, SAIA (410) 297-6363 RITE AID FIXTURE DISTRIBUTION CENTER YRC, FEDEX, ESTES, 325 Welltown Road N/A N/A 0145788920023 OLD DOMINION Winchester, VA 22603 (540) 662-3552 PONTIAC DISTRIBUTION CENTER* YRC, FEDEX, ESTES, OLD 5400 Perry Drive Perry Drug Stores 002230PIY 0145788920029 DOMINION, SAIA Waterford, MI 48329 (248) 674-7770 ICE CREAM DIVISION YRC, FEDEX, ESTES, OLD 9200 Telstar Avenue ---------------------- N/A 0145788920061 DOMINION, SAIA El Monte, CA 91731 (626) 571-0122 WILSONVILLE DISTRIBUTION CENTER YRC, FEDEX, ESTES, OLD 29555 SW Boones Ferry Road Thrifty Payless Inc N/A 0145788920080 DOMINION, SAIA Wilsonville, OR 97070 (503) 685-6013 WOODLAND DISTRIBUTION CENTER* 1755 East Beamer Street YRC, FEDEX, ESTES, OLD Thrifty Payless INC RT0223874 0145788920081 Woodland, CA 95776 DOMINION, SAIA (530) 661-1800 x124 LANCASTER DISTRIBUTION CENTER YRC, FEDEX, ESTES, OLD 2801 West Avenue H Thrifty Payless INC N/A 0145788920088 DOMINION, SAIA Lancaster, CA 93536 (661) 951-7565 Contact the Rite Aid Transportation Department with any questions regarding Rite Aid Preferred Carriers and inbound routing prior to shipping. -

Sunshine in the Black Box of Pharmacy Benefits Management

Florida Medicaid Pharmacy Claims Analysis January 27, 2020 Prepared for the Florida Pharmacy Association (FPA) and American Pharmacy Cooperative Inc. (APCI) 0 | Page 1 ABOUT THIS REPORT The Florida Pharmacy Association (FPA) and American Pharmacy Cooperative, Inc. (APCI) commissioned 3 Axis Advisors LLC to study the Florida Medicaid program with the initial intention of understanding the impact of spread pricing on Florida’s small community pharmacy providers. Our prior work has found strong evidence of spread pricing in Medicaid programs in New York, Illinois, and Michigan, while state government work in Ohio, Kentucky, Georgia, Virginia, and Maryland has definitively quantified spread in their state’s Medicaid programs as well. 1, 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 While we did not have all of the data required to perform an audit to completely pinpoint spread pricing in Florida Medicaid, it was the hope of FPA and APCI that we could perform a transparent assessment of spread in Florida, with the goal of providing any evidence to the state for it to research further. As we started to gather data, we realized that Florida – owing to its laudable commitment to transparency – offered a unique opportunity to go well beyond spread pricing in our data analysis. The more than 350 million deidentified claims obtained through a Freedom of Information Act Request to the Agency for Health Care Administration (AHCA) gave us the most robust dataset to study how all funds related to outpatient prescription drugs flow through Medicaid. This dataset gave us the ability to definitively see what each managed care organization (MCO) reported paying for each drug – National Drug Code (NDC) – to each pharmacy – National Provider Identifier (NPI). -

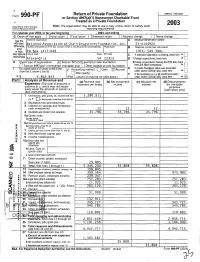

Return of Private Foundation P Or Section 4947(A)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated As a Private Foundation

OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990- Return of Private Foundation P or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department or the Treasury Note . The organization may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state 2003 Interna l Revenue Service I reporting requirements For calendar ear 2003, or tax ear beginning , 2003, and ending , G Check all that app ly Initial return Final return Amended return Address chan ge Name cha Name of organization Employer identification number Use the A Isslabel . National Association of Chain Dru g stores Foundation, Inc . 51-0144922 0thBfWISC, Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) pant or type. PO Box 1417-D49 (703) 549-3001 See Specific ary or town - State ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here 0" I Instructions. Al exdnd r id VA 22313 D 1 Foreign organizations, check here H Check type of organization X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check DO. n Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation here and attach computation El E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value o a assets at end of year ~ Accounting method . Cash X Accrual (from Part fl, column c, line 16) I U U under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination ~ $ 4,862,843 . -

J C PENNEY CO INC Form 10-K Annual Report Filed 2012-03-28

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 10-K Annual report pursuant to section 13 and 15(d) Filing Date: 2012-03-28 | Period of Report: 2012-01-28 SEC Accession No. 0001193125-12-135077 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER J C PENNEY CO INC Business Address 6501 LEGACY DRIVE CIK:1166126| IRS No.: 260037077 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 0131 PLANO TX 75024-3698 Type: 10-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-15274 | Film No.: 12718395 9722431100 SIC: 5311 Department stores Copyright © 2014 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D. C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) x ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended January 28, 2012 or ¨ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission file number 001-15274 J. C. PENNEY COMPANY, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 26-0037077 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 6501 Legacy Drive, Plano, Texas 75024-3698 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (972) 431-1000 (Registrants telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of each exchange on which Title of each class registered Common Stock of 50 cents par value New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

CVS Caremark Corporation 2007 Annual Report

The Power of One :MJ:Xi\dXib:figfiXk`fe)''.8eelXcI\gfik K89C<F=:FEK<EKJ Table of Contents K_\Gfn\if]Fe\ ( :_X`idXeËjC\kk\ikfJ_Xi\_fc[\ij . K_fl^_kj=ifdFliGi\j`[\ekj (( :MJ&g_XidXZp () :Xi\dXibG_XidXZpJ\im`Z\j (+ D`elk\:c`e`Z (- JkfZbG\i]fidXeZ\ (. DXeX^\d\ekËj;`jZljj`feXe[8eXcpj`jf] =`eXeZ`Xc:fe[`k`feXe[I\jlckjf]Fg\iXk`fej (/ DXeX^\d\ekËjI\gfikfe@ek\ieXc:fekifc Fm\i=`eXeZ`XcI\gfik`e^ *. I\gfikf]@e[\g\e[\ekI\^`jk\i\[ GlYc`Z8ZZflek`e^=`id */ :fejfc`[Xk\[JkXk\d\ekjf]Fg\iXk`fej *0 :fejfc`[Xk\[9XcXeZ\J_\\kj +' :fejfc`[Xk\[JkXk\d\ekjf]:Xj_=cfnj +( :fejfc`[Xk\[JkXk\d\ekjf] J_Xi\_fc[\ijË<hl`kp +) Efk\jkf:fejfc`[Xk\[=`eXeZ`XcJkXk\d\ekj ++ =`m\$P\Xi=`eXeZ`XcJlddXip -0 I\gfikjf]@e[\g\e[\ekI\^`jk\i\[ GlYc`Z8ZZflek`e^=`idj .' J_Xi\_fc[\i@e]fidXk`fe .) :fddle`kpFlki\XZ_ @ej`[\9XZb:fm\i FLIE<N:FDG8EP%%%K?<GFN<IF=FE< :MJ:Xi\dXib`jk_\cXi^\jk`ek\^iXk\[gifm`[\if]gi\jZi`gk`fejXe[ i\cXk\[_\Xck_j\im`Z\j`ek_\Le`k\[JkXk\j#Ôcc`e^fidXeX^`e^dfi\ k_Xe(Y`cc`fegi\jZi`gk`fejXeelXccp%8jXi\jlck#n\ZXegifXZk`m\cp`e]fid Xe[\e^X^\Zfejld\ijkfkXb\Zfekifcf]k_\`i_\Xck_#le`hl\cpgfj`k`fe`e^ ljkf[i`m\gfj`k`m\flkZfd\jXkXcfn\iZfjk%@eX[[`k`fekffg\iXk`e^ k_\eXk`feËjcXi^\jkeldY\if]i\kX`cg_XidXZ`\jXe[i\kX`c$YXj\[_\Xck_ Zc`e`Zj#n\f]]\iX]lcciXe^\f]gi\jZi`gk`feY\e\ÔkdXeX^\d\ekj\im`Z\j kfgcXejgfejfij%N\Xi\Xcjffe\f]k_\c\X[`e^gifm`[\ijf]D\[`ZXi\ GXik;gi\jZi`gk`fegcXej% N\\dgcfpdfi\k_Xe(0'#'''Zfcc\X^l\j`e++jkXk\jXe[k_\;`jki`Zk f]:fcldY`X%8kp\Xi$\e[#n\fg\iXk\[-#)+,:MJ&g_XidXZpjkfi\j#+-) D`elk\:c`e`ZcfZXk`fej#,-i\kX`cjg\Z`Xckpg_XidXZpjkfi\j#)'jg\Z`Xckp dX`cfi[\ig_XidXZ`\j#e`e\dX`cj\im`Z\g_XidXZ`\j#Xe[fli:MJ%Zfd