National Board Seder Companion 5780

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Live Israel.Learn Israel.Love Israel

HACHSHARA 2013 Live Israel. Learn Israel. Love Israel. MTA LIMMUD Welcome to the Our team world of Hachshara! Bnei Akiva has a highly qualified administrative and educational staff in Israel, looking after the programmes Bnei Akiva inspires and empowers Jewish youth and participants on a daily basis. with a deep commitment to the Jewish people, the Land of Israel and the Torah. Its members . Qualified resident leaders (madrichim) – among them, Israelis on their second year of National Service – strive to live lives of Torah va’Avodah, combining accompany our groups, guiding and advising them Torah learning and observance with active throughout their year in Israel. contribution to the Jewish people and society. The programme co-ordinator (rakaz) is responsible for For more than 80 years, our Hachshara the logistical and educational implementation of the programmes have played a part in shaping and programme. He visits the group regularly and maintains training the future leaders of Bnei Akiva and close contact with the madrichim. Jewish communities around the world. Our groups are also cared for by educational mentors, a Your gap year is when you can devote specific young family who look after the welfare needs of those on Hachshara. As experienced graduates of Bnei Akiva, time to Jewish learning, and Hachshara is they help to guide our participants individually so that designed to help you make the most of that they gain the most out of their year. time. And you’ll find that being on Hachshara is a learning experience itself – you’ll find out more about Israel, pick up Ivrit and grow as a person. -

CHRONICLE NEVEH SHALOM March/April 2010 Adar-Iyyar- 5770 No

CONGREGATIONCHRONICLE NEVEH SHALOM March/April 2010 Adar-Iyyar- 5770 No. 5 This newsletter is supported by the Sala Kryszek Memorial Publication Fund From the Pulpit From the President Only A Hint The winter months have proven to For most of us, the smells and sounds of our be very busy for your Board of Directors and Pesach Seder evoke treasured memories. Though Committees, and just like the seasons of the for me, as a young child, this was not always year, Spring looks to be bringing with it new the case. Frightened to sing in front of a crowd, challenges illed with great potential. reluctant to snap on a tie, my parents had to bribe The Cantorial Transition Committee me to say the four questions…and geilte ish has completed its work. You can read their and horseradish was not exactly my favorite of inal report to the Board of Directors on our combinations. website at http://www.nevehshalom.org/ Nevertheless, Pesach has become one of my favorite holidays. I iles/cantorial_recommendation.pdf. This have joined the ranks of Jews throughout the world who have committee did excellent work in reviewing made the Seder the most celebrated ritual in modern Jewish life. I various Cantorial models and making have grown to love the Hillel sandwich. And yet, with my newfound recommendations on moving forward as adoration I have noticed something troublesome. Inevitably at every we now enter the process of conducting a Seder, there is always at least one relative who nudges, “How long till search for a replacement. The Cantor Search we eat? Let’s make this a quick one!” Committee held its irst meeting in February, What is the rush? We have likened ourselves to our ancient has received many resumes and may have Israelite ancestors. -

The Constitution of Bnei Akiva New Zealand Incorporated

The Constitution of Bnei Akiva New Zealand Incorporated We believe in the Torah, we believe in Avodah, we Believe in Aliyah, ‘cause we are Bnei Akiva! ___________________________________________________________________________ Note: This constitution has been amended since its passage in 1997. This version includes all amendments from 2002 until 2008, which are so marked to indicate their later addition. This constitution was updated and significantly reformatted in 2015. Amendments made in 2015 are not marked. Amendments made from 2015 onward are marked. ___________________________________________________________________________ Contents Part I 7 Name General Provisions of the Constitution 8 Ideology 9 Aims 1 Title 10 Commitment to Halacha 2 Commencement 11 Use or Possession of Cigarettes, 3 Purpose Drugs, Weapons or Dangerous Items 4 Interpretation 12 Motto 5 Amendments 13 Anthem 6 Publication 14 Emblem Part II 15 Common Seal The Tnua 16 Official Greeting 17 Official Uniform 46 Officers 18 Official Affiliations 47 Election of Officers 48 Appointment of Interim Replacement Part III Membership Subpart 3 Sniffim Subpart 1 Chanichim 49 Location 50 Affiliation 19 Membership 51 Officers 20 Powers and Duties 52 Election of Officers 21 Shevatim 53 Appointment of Interim Replacement 22 List of Shevatim 54 Tochniot Subpart 2 55 Madrich Meetings Madrichim Part V 23 Membership Finances of Bnei Akiva 24 Powers and Duties 56 Division of Expenses 25 Dugmah 57 Bank Accounts Subpart 3 58 Powers and Duties of the Gizbar Artzi Shlichim 59 Borrowing Money -

SUMMER 2019 Inspiration

SUMMER 2019 Inspiration Mach Hach BaAretz is Bnei Akiva’s summer Fr tour of Israel for teens completing the tenth grade. iends for Life It is the largest and most popular program of its kind, with over 300 participants every summer. Mach Hach offers a wide range of diverse programs to match the varied interests of each individual. This year we are offering Mach One of the most outstanding features of Mach Hach is the relationships you will create Hach Adventure and Mach Hach Hesder. with both friends and staff. Before the summer, groups of 35-43 campers are assigned In Bnei Akiva, love of Israel is not a slogan, but a passion. to a bus. In this intimate setting, every camper can be fully appreciated and feel that Mach Hach has led tours of Israel every summer for over forty- they belong. Each group takes on a life of its own with a distinct personality and five years, in good times and bad. Helping our participants character. Mach Hach “buses” have reunions for years to come. develop an everlasting bond with Israel is at the forefront of our Each bus has its own itinerary, fine-tuned by its individual mission. This goal guides every aspect of our touring experience, staff. Every bus has six staff members: a Rosh Bus (Head from staffing to itinerary planning to program development. Counselor), a tour guide, a logistics coordinator and three Racheli Hamburger Mach Hach is not just another tour of Israel, but an authentic counselors. Staff members serve as role models and Cedarhurst, NY Israel experience. -

B I M a H N O T

בס“ד Congregation Beth Israel Abraham and Voliner BIMAH NOTES Our Mission: To be a welcoming, caring and spirited Orthodox congregation that enables and inspires our members, our children and all Jews to deepen their Shabbat Parshat Re’Eh—Rosh Chodesh Elul commitment to live, learn and love Torah, applying it to everyday living in the modern world. www.biav.org Congregation BIAV Biavkc / biavminyan EREV SHABBAT D’VAR TORAH This Coming Week Shabbat Zmanim: Norm Glass will deliver this Friday’s D’var Torah. Happy Birthday! Friday Mincha 7:00 PM Candle lighting 7:34 PM SHABBAT DRASHA Eitan Miller Eliana Silver Shacharit 9:00 AM Rabbi Mizrahi will speak. Leo Cohen Dana Morgen Mincha 7:10 PM SHABBAT SHIUR—6:25 PM Autumn Shemitz Barry Krigel Shabbat ends 8:32 PM Rabbi Rubin: “How True Does the False Prophet Have To Be?” Phyllis Carozza Alison Heisler David Horesh MAZEL TOV Ben Kopelman Joe Krashin YAHRZEITS To Livia Noorollah as she celebrates her Bat Mitzvah this Leah Attias September 1—1 Elul weekend surrounded by her proud parents, brothers, and Abe Sultanik their guests. Happy Anniversary! Jacob Tulchinsky Jason & Eva Sokol September 2—2 Elul MAZEL TOV Zalman & Veta Benny Shapiro Mullokandov To Gili Beer and Katriel Kennedy Matt & Bonnie Siegel September 5—5 Elul Samuel Rosenberg on their recent marriage in Israel. Rabbi Daniel and Ayala Rockoff September 6—6 Elul David & Dana Horesh Zacharias Wurzburger IMPORTANT BIAV SECURITY EVENT Sunday morning, September 15, 9:15 AM We are hoping to have 100% participation of our SHABBAT FORECAST members! Please put this important date on your calendar, and RSVP by Monday September 9th for all members of your family to the office at [email protected] (We want to ensure we have enough babysitters & food.) Join us for a morning of small sessions to educate the community about security, fire safety, natural disasters and medical emergencies - followed by lunch for those who participate at each station! There will be age-appropriate Low 68° High 79° education for children, as well as babysitting. -

Read Torat Habayit

TORAT HABAYIT THE JOURNAL OF BNEI AKIVA UK | 1 2019/5779 IDEOLOGY: 80 YEARS ON A STUDY ON THE CHALLENGES FACING OUR IDEOLOGY IN THE MODERN DAY 2 Editorial 3 Introduction from the Mazkirut 4 Bnei Akiva’s ideology and the future Rav Aharon Herskovitz 7 Should Bnei Akiva interact with other youth movements? Josh Zeltser 10 Is Bnei Akiva a kiruv movement Dani Jacobson 12 An inconsistent triad: Modern Orthodoxy, Religious Zionism, and the limits of modernity Jemma Silvert 16 Reflections on how Bnei Akiva UK decides its ideology Noah Haber 20 Does Chalutziut still exist? Shulamit Finn 22 Ben shmonim lagvura: The exceptional strength of Bnei Akiva Hannah Reuben Torat HaBayit is the journal of Bnei Akiva UK, which aims to stimulate ideological debate within the movement and to inform the wider community of the issues at the cutting edge of the contemporary consciousness of the Jewish people. The views expressed in Torat HaBayit are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Bnei Akiva UK. The editors would particularly like to thank Rabbanit Shira Herskovitz and Eli Maman for their invaluable help and advice throughout this project TORAT HABAYIT THE JOURNAL OF BNEI AKIVA UK | 1 2 | TRAT HABAYIT THE OURNA F BNEI AKIVA K 2019/5779 '"כולהו סתימתאה אליבא דרבי עקיבא"1 – פלגים רבים הולכים וזורמים, אבל הכול בא מתוך IDEOLOGY: 80 YEARS ON אותו ים הגדול, תורתו הכוללת של רבי עקיבא'A STUDY ON THE CHALLENGES FACING OUR IDEOLOGY IN THE MODERN DAY 2 ‘”All these conclusions follow Rabbi Akiva’s opinion” – many streams flow down, but all 2 Editorial come from the same ocean, the all-encompassing Torah of Rabbi Akiva.’ In a letter to Bnei Akiva, then a nascent youth movement in the pre-State and of Israel, Rav 3 Introduction from the Mazkirut Kook looks to Rabbi Akiva, upon whom the movement was named, for inspiration, to outline aims for the movement to impact their generation. -

Other Developments SERVICES to the COMMUNITY and ITS

142 AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK Kansas City reported its first referrals from a Federal penitentiary and state psychiatric hospitals. Other Developments During this period several smaller Jewish communities began to plan the establishment of a vocational service facility on a part-time basis. Four additional agencies introduced fees for vocational guidance service, making a total of eight (Cleveland, Boston, Houston, Cincinnati, Denver, Milwaukee, New York City, and Philadelphia), and three agencies (Kansas City, Mo., Houston, and Montreal) expanded staff to meet more of their local needs. The Jewish Occupational Council and JVS agencies were consulted by Hadassah, The Women's Zionist Organization of America and the Israel Consulate for the development of more adequate vocational service facilities in Israel. The JVS agencies were used to assist Israeli students in the United States and to help train vocational service personnel for Israel. ROLAND BAXT SERVICES TO THE COMMUNITY AND ITS YOUTH EWISH community centers exist throughout the United States to provide American Jews with opportunities for group experience which will satisfy Jtheir individual and group needs. Many national Jewish organizations spon- sor youth-serving programs to fulfill similar purposes for their young people. The Jewish Community Center In 1951 the number of Jewish community centers and Young Men's and Women's Hebrew Associations in the United States affiliated with the Na- tional Jewish Welfare Board (JWB) increased to 337. This represented a rise of 42 from the total of 295 in 1946, at the end of World War II. The aggre- gate number of individuals served by centers increased 2 per cent over the number served in 1950 to reach an estimated total of 514,000; the propor- tionate increase since 1946 was 15.5 per cent. -

Orthodox Students Are Em...Wish Telegraphic Agency

5/18/2015 Orthodox students are embracing social action | Jewish Telegraphic Agency Orthodox students are embracing social action By Amy Klein November 16, 2009 11:46pm NEW YORK (JTA) — A few months after Hurricane Ike hit Galveston, Texas, in September 2008, Yeshiva University student David Eckstein went to the devastated area with 32 other students to help rebuild homes. “The doors hadn’t been opened since the hurricane. We took the house apart and started rebuilding it, trying to rebuild someone’s life,” said Eckstein, 23, of West Yeshiva University students getting a lesson on how to repair Hempstead, N.Y. and paint streets in urban Houston. (Yeshiva University) “When you picture something on the news, it’s hard to imagine it, but when you go in person to see the damaged that was done and the lives that were ruined, it’s not just the impact you have on them but the impact is much stronger on the volunteers.” Eckstein felt so moved by the experience — and volunteering at California soup kitchens the year before — that now he is spending a year as a Yeshiva University presidential fellow working with the school’s Center for the Jewish Future, a department founded in 2005 to train future communal leaders and engage them in various causes within the Jewish world and beyond. “I think we have to realize we have a responsibility to the world around us, that we’re not just people of change for ourselves and our community,” Eckstein said. He added that the biblical commandment of tikkun olam — repairing the world — creates an obligation to help all people, “even though they’re not Jewish.” Even though they’re not Jewish. -

FROM the EDITOR, ALY PAVELA NFTY Membership And

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE NORTH AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEMPLE YOUTH NFTY CONVENTION EDITION. FEBRUARY 2011. DALLAS, TEXAS NFTY is not only our programs or events or meetings. NFTY is a community of individuals – teens, staff, FROM THE EDITOR, ALY PAVELA friends, volunteers, and teachers, each with a NFTY Membership and Communications story and a life and a spirit. Vice-President NFTY is a place where teens hang out with teens; Convention is a lot to handle. Hundreds of And NFTY is a place where Jews do Jewish. foreign teens, a new city, crazy programming and various different NFTY strives to understand multiple points of view demoninations of Reform Judaism. And, of even if we disagree. course, all the different accents. NFTY strives to take stands in concert with But instead of being overwhelmed, I hope Reform Jewish values and to take action based you were open. I hope you opened your on those stands. mind to different points of view, to different NFTY strives to live within the flow of Reform kinds of people and ways of being a Reform Jewish values and text. Jew. I hope you turned the the person next NFTY strives to develop leaders and mentors to you at dinner and extended your hand. If beginning when teens walk in our doors. you didn’t, there’s still time. You have a whole bus ride to the airport. You still have NFTY Evolves. the rest of your NFTY career. So I challenge So? How are you going to help NFTY evolve? you to open yourselves up. -

All Positions.Xlsx

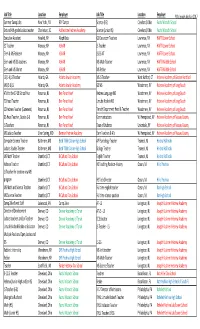

Job Title Location Employer Job Title Location Employer YU's Jewish Job Fair 2017 Summer Camp Jobs New York , NY 92Y Camps Science (HS) Cleveland, Ohio Fuchs Mizrachi School 3rd and 4th grade Judaics teacher Charleston, SC Addlestone Hebrew Academy Science (Junior HS) Cleveland, Ohio Fuchs Mizrachi School Executive Assistant Hewlett, NY Aleph Beta GS Classroom Teachers Lawrence, NY HAFTR Lower School EC Teacher Monsey, NY ASHAR JS Teacher Lawrence, NY HAFTR Lower School Elem & MS Rebbeim Monsey, NY ASHAR JS/GS AT Lawrence, NY HAFTR Lower School Elem and MS GS teachers Monsey, NY ASHAR MS Math Teacher Lawrence, NY HAFTR Middle School Elem and MS Morot Monsey, NY ASHAR MS Rebbe Lawrence, NY HAFTR Middle School LS (1‐4) JS Teacher Atlanta, GA Atlanta Jewish Academy MS JS Teacher‐ West Hatford, CT Hebrew Academy of Greater Hartford MS (5‐8) JS Atlanta, GA Atlanta Jewish Academy GS MS Woodmere, NY Hebrew Academy of Long Beach ATs for the 17‐18 School Year Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Hebrew Language MS Woodmere, NY Hebrew Academy of Long Beach EC Head Teacher Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Limudei Kodesh MS Woodmere, NY Hebrew Academy of Long Beach EC Hebrew Teacher (Ganenent) Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Tanach Department Head & Teacher Woodmere, NY Hebrew Academy of Long Beach GS Head Teacher, Grades 1‐8 Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Communications W. Hempstead, NY Hebrew Academy of Nassau County JS Teachers Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Dean of Students Uniondale, NY Hebrew Academy of Nassau County MS Judaics Teacher Silver Spring, MD Berman Hebrew Academy Elem Teachers & ATs W. -

Teen Israel Experience Application 2020-2021

Teen Israel Experience Application 2020-2021 The Teen Israel Experience grant is for rising juniors and seniors in high school. Your child is eligible for a grant of up to $3000. Please answer questions below to start the application process. Parents, you may fill out the application yourself, or ask your child to do so. In either case, your child will need to complete the teen impact questions on the last page. Please save your answers and email to [email protected] and for any assistance. Student Information Name: Address: Phone number: E-mail address: Gender: Date of birth: (MM/DD/YYYY) Parent/Guardian 1 Information Name: Address (if different from student): Cell phone number: E-mail address: Parent/Guardian 2 Information Name: Address (if different from student): Cell phone number: E-mail address: What is your child's current grade level? 10th Grade 11th Grade Where does your child go to high school? What is the name of the Israel program your child will be participating in? Please enter full name of organization and program (ex. “BBYO March of the Living,” not “March of the Living,” or “NFTY L’Dor V’Dor,” not “NFTY”). What are the dates of the program? What is your family synagogue affiliation? Please select all that apply. ASBEE Beth Sholom Or Chadash Young Israel Baron Hirsch Chabad Temple Israel None Has your child ever been to Israel? Please select all that apply. Yes, on a private family trip Yes, with family on an organized group such as a synagogue mission Yes, on a school trip Yes, with a youth or teen program No, -

Engaging Jewish Teens: a Study of New York Teens, Parents and Pracɵɵoners

Engaging Jewish Teens: A Study of New York Teens, Parents and PracƟƟoners Methodological Report Amy L. Sales Nicole Samuel Alexander Zablotsky November 2011 Table of Contents Method.............................................................................................................................................................................1 Parent and Teen Surveys ...............................................................................................................................................1 Youth Professionals Survey ...........................................................................................................................................4 Sample ......................................................................................................................................................................4 Parent Survey ...................................................................................................................................................................5 Welcome! .....................................................................................................................................................................5 To Begin ........................................................................................................................................................................5 Background ...................................................................................................................................................................6