Variation in the Juvenal Plumage of the Red-Legged Shag (Phalacrocorax Gaimardi) and Notes on Behavior of Juveniles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Namibia & the Okavango

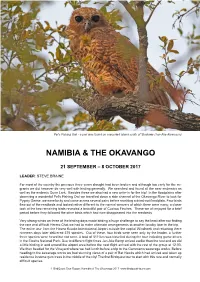

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

Phylogenetic Patterns of Size and Shape of the Nasal Gland Depression in Phalacrocoracidae

PHYLOGENETIC PATTERNS OF SIZE AND SHAPE OF THE NASAL GLAND DEPRESSION IN PHALACROCORACIDAE DOUGLAS SIEGEL-CAUSEY Museumof NaturalHistory and Department of Systematicsand Ecology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045-2454 USA ABSTRACT.--Nasalglands in Pelecaniformesare situatedwithin the orbit in closelyfitting depressions.Generally, the depressionsare bilobedand small,but in Phalacrocoracidaethey are more diversein shapeand size. Cormorants(Phalacrocoracinae) have small depressions typical of the order; shags(Leucocarboninae) have large, single-lobeddepressions that extend almost the entire length of the frontal. In all PhalacrocoracidaeI examined, shape of the nasalgland depressiondid not vary betweenfreshwater and marine populations.A general linear model detectedstrongly significant effectsof speciesidentity and gender on size of the gland depression.The effectof habitat on size was complexand was detectedonly as a higher-ordereffect. Age had no effecton size or shapeof the nasalgland depression.I believe that habitat and diet are proximateeffects. The ultimate factorthat determinessize and shape of the nasalgland within Phalacrocoracidaeis phylogenetichistory. Received 28 February1989, accepted1 August1989. THE FIRSTinvestigations of the nasal glands mon (e.g.Technau 1936, Zaks and Sokolova1961, of water birds indicated that theseglands were Thomson and Morley 1966), and only a few more developed in species living in marine studies have focused on the cranial structure habitats than in species living in freshwater associatedwith the nasal gland (Marpies 1932; habitats (Heinroth and Heinroth 1927, Marpies Bock 1958, 1963; Staaland 1967; Watson and Di- 1932). Schildmacher (1932), Technau (1936), and voky 1971; Lavery 1972). othersshowed that the degree of development Unlike most other birds, Pelecaniformes have among specieswas associatedwith habitat. Lat- nasal glands situated in depressionsfound in er experimental studies (reviewed by Holmes the anteromedialroof of the orbit (Siegel-Cau- and Phillips 1985) established the role of the sey 1988). -

South Africa Mega Birding III 5Th to 27Th October 2019 (23 Days) Trip Report

South Africa Mega Birding III 5th to 27th October 2019 (23 days) Trip Report The near-endemic Gorgeous Bushshrike by Daniel Keith Danckwerts Tour leader: Daniel Keith Danckwerts Trip Report – RBT South Africa – Mega Birding III 2019 2 Tour Summary South Africa supports the highest number of endemic species of any African country and is therefore of obvious appeal to birders. This South Africa mega tour covered virtually the entire country in little over a month – amounting to an estimated 10 000km – and targeted every single endemic and near-endemic species! We were successful in finding virtually all of the targets and some of our highlights included a pair of mythical Hottentot Buttonquails, the critically endangered Rudd’s Lark, both Cape, and Drakensburg Rockjumpers, Orange-breasted Sunbird, Pink-throated Twinspot, Southern Tchagra, the scarce Knysna Woodpecker, both Northern and Southern Black Korhaans, and Bush Blackcap. We additionally enjoyed better-than-ever sightings of the tricky Barratt’s Warbler, aptly named Gorgeous Bushshrike, Crested Guineafowl, and Eastern Nicator to just name a few. Any trip to South Africa would be incomplete without mammals and our tally of 60 species included such difficult animals as the Aardvark, Aardwolf, Southern African Hedgehog, Bat-eared Fox, Smith’s Red Rock Hare and both Sable and Roan Antelopes. This really was a trip like no other! ____________________________________________________________________________________ Tour in Detail Our first full day of the tour began with a short walk through the gardens of our quaint guesthouse in Johannesburg. Here we enjoyed sightings of the delightful Red-headed Finch, small numbers of Southern Red Bishops including several males that were busy moulting into their summer breeding plumage, the near-endemic Karoo Thrush, Cape White-eye, Grey-headed Gull, Hadada Ibis, Southern Masked Weaver, Speckled Mousebird, African Palm Swift and the Laughing, Ring-necked and Red-eyed Doves. -

REVIEWS Edited by J

REVIEWS Edited by J. M. Penhallurick BOOKS A Field Guide to the Seabirds of Britain and the World by is consistent in the text (pp 264 - 5) but uses Fleshy-footed Gerald Tuck and Hermann Heinzel, 1978. London: Collins. (a bette~name) in the map (p. 270). Pp xxviii + 292, b. & w. ills.?. 56-, col. pll2 +48, maps 314. 130 x 200 mm. B.25. Parslow does not use scientific names and his English A Field Guide to the Seabirds of Australia and the World by names follow the British custom of dropping the locally Gerald Tuck and Hermann Heinzel, 1980. London: Collins. superfluous adjectives, Thus his names are Leach's Storm- Pp xxviii + 276, b. & w. ills c. 56, col. pll2 + 48, maps 300. Petrel, with a hyphen, and Storm Petrel, without a hyphen; 130 x 200 mm. $A 19.95. and then the Fulmar, the Gannet, the Cormorant, the Shag, A Guide to Seabirds on the Ocean Routes by Gerald Tuck, the Kittiwake and the Puffin. On page 44 we find also 1980. London: Collins. Pp 144, b. & w. ills 58, maps 2. Storm Petrel but elsewhere Hydrobates pelagicus is called 130 x 200 mm. Approx. fi.50. the British Storm-Petrel. A fourth variation in names occurs on page xxv for Comparison of the first two of these books reveals a ridi- seabirds on the danger list of the Red Data Book, where culous discrepancy in price, which is about the only impor- Macgillivray's Petrel is a Pterodroma but on page 44 it is tant difference between them. -

(Nematoda: Anisakidae) in Fish-Eating Birds from Zimbabwe

Article — Artikel First record of Contracaecum spp. (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in fish-eating birds from Zimbabwe M Barsona* and B E Marshalla 2002), of which the reed cormorant Phalacrocorax africanus (Gmelin, 1789), the ABSTRACT white-breasted cormorant P.carbo (L.), the Endoparasites of fish-eating birds, Phalacrocorax africanus, P.carbo, Anhinga melanogaster and darter Anhinga melanogaster Lacapéde & Ardea cinerea collected from Lake Chivero near Harare, Zimbabwe, were investigated. Adult Dauchin, 1802, and the grey heron Ardea Contracaecum spp. were found in the gastrointestinal tract (prevalence 100 % in P.africanus, P. carbo and A. melanogaster;25%inA. cinerea). Parasite intensity was 11–24 (mean 19) in cinerea (L.), were selected because of their P. africanus, 4–10 (mean 7) in P. carbo, 4–56 (mean 30) in A. melanogaster and 2 (mean 0.5) in abundance on the lake. A. cinerea. The cormorants fed mainly on cichlid fishes and carp; the darters and the grey herons on cichlids. All these fishes are intermediate hosts of Contracaecum spp. Scanning MATERIALS AND METHODS electron microscopy revealed that Contracaecum rudolphii infected both cormorant species Four reed cormorants, 4 white-breasted and darters; C. carlislei infected only the cormorants while C. tricuspis and C. microcephalum cormorants, four darters and four grey infected only the darters. Parasites from the grey heron were not identified to species herons were shot with a 0.22 rifle and a because they were still developing larvae. These parasites are recorded in Zimbabwe for the 12-bore shotgun firing buckshot at Lake first time. Chivero. Their beaks were sealed with Key words: Contracaecum, Lake Chivero, mean intensity, nematode, parasite prevalence, rubber bands to prevent the escape of piscivorous bird, Zimbabwe. -

Mate Similarity in Foraging Kerguelen Shags

Mate similarity in foraging Kerguelen shags: a combined bio-logging and stable isotope investigation Elodie Camprasse, Yves Cherel, John Arnould, Andrew Hoskins, Paco Bustamante, Charles-André Bost To cite this version: Elodie Camprasse, Yves Cherel, John Arnould, Andrew Hoskins, Paco Bustamante, et al.. Mate similarity in foraging Kerguelen shags: a combined bio-logging and stable isotope investigation. Marine Ecology Progress Series, Inter Research, 2017, 578, pp.183 - 196. 10.3354/meps12259. hal-01621024 HAL Id: hal-01621024 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01621024 Submitted on 22 Oct 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Mate similarity in foraging Kerguelen shags: a combined bio-logging and stable isotope investigation Elodie C.M. Camprasse1,*, Yves Cherel2, John P.Y. Arnould1, Andrew J. Hoskins3, Paco Bustamante4, Charles-André Bost2 1 School of Life and Environmental Sciences (Burwood Campus), Deakin University, Geelong, 3220, Australia 2 Centre d’Etudes Biologique de Chizé (CEBC), UMR 7372 CNRS-Université de La Rochelle, 79360 Villiers-en-Bois, France 3 CSIRO Land and Water, Canberra, 2601 Australian Capital Territory, Australia 4 Littoral Environnement et Sociétés (LIENSs), UMR 7266 CNRS-Université de La Rochelle, 2 rue Olympe de Gouges, 17000 La Rochelle, France *Corresponding author: [email protected] 1 ABSTRACT Similarity or dissimilarity between 2 individuals that have formed a pair to breed can occur in morphology, behaviour and diet. -

Table Mountain National Park

BIRDS OF TABLE MOUNTAIN NATIONAL PARK The Cape Peninsula has many records of vagrant species blown by storms, ship assisted or victims of reverse migration Bolded [1] depicts vagrant species Rob # English (Roberts 7) English (Roberts 6) Table Mountain 1 Common Ostrich Ostrich 1 2 King Penguin King Penguin [1] 2.1 Gentoo Penguin (925) Gentoo Penguin [1] 3 African Penguin Jackass Penguin 1 4 Rockhopper Penguin Rockhopper Penguin [1] 5 Macaroni Penguin Macaroni Penguin [1] 6 Great Crested Grebe Great Crested Grebe 1 7 Blacknecked Grebe Blacknecked Grebe 1 8 Little Grebe Dabchick 1 9 Southern Royal Albatross Royal Albatross 1 9.1 Northern Royal Albatross 1 10 Wandering Albatross Wandering Albatross 1 11 Shy Albatross Shy Albatross 1 12 Blackbrowed Albatross Blackbrowed Albatross 1 13 Greyheaded Albatross Greyheaded Albatross 1 14 Atlantic Yellownosed Albatross Yellownosed Albatross 1 15 Sooty Albatross Darkmantled Sooty Albatross 1 16 Lightmantled Albatross Lightmantled Sooty Albatross 1 17 Southern Giant-Petrel Southern Giant Petrel 1 18 Northern Giant-Petrel Northern Giant Petrel 1 19 Antarctic Fulmar Antarctic Fulmar 1 21 Pintado Petrel Pintado Petrel 1 23 Greatwinged Petrel Greatwinged Petrel 1 24 Softplumaged Petrel Softplumaged Petrel 1 26 Atlantic Petrel Atlantic Petrel 1 27 Kerguelen Petrel Kerguelen Petrel 1 28 Blue Petrel Blue Petrel 1 29 Broadbilled Prion Broadbilled Prion 1 32 Whitechinned Petrel Whitechinned Petrel 1 34 Cory's Shearwater Cory's Shearwater 1 35 Great Shearwater Great Shearwater 1 36 Fleshfooted Shearwater Fleshfooted -

The Endangered Bank Cormorant Phalacrocorax Neglectus: the Heat Is On

The endangered bank cormorant Phalacrocorax neglectus: the heat is on Understanding the effect of climate change and associated environmental variable changes on the breeding biology and population dynamics of the bank cormorant in the Western Cape, South Africa Corlia Meyer MYRCOR004 ThesisUniversity presented for the Degree of of MasterCape of Science Town in Zoology, Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Cape Town, South Africa April 2014 Supervisors: Prof. L.G. Underhill, Prof. P.G. Ryan, Dr R.B. Sherley and Dr T. Cook The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Plagiarism declaration I know the meaning of plagiarism and declare that all of the work in this thesis, saved for that which is properly acknowledged, is my own. Signature:________________________ Date:_____________________________ i ii For the birds iii iv Abstract The bank cormorant Phalacrocorax neglectus was listed as ‘Endangered’ in 2004, following a decrease of more than 60% in the total population from 1975–2011. It ranges from central Namibia to the Western Cape, South Africa, with most of the population occurring on offshore islands in Namibia. The main reason for this study was to determine if climate change could be identified as a factor which has influenced the decreasing numbers of bank cormorants. -

ZIMBABWE CHECKLIST R=Rare, V=Vagrant, ?=Confirmation Required

ZIMBABWE CHECKLIST R=rare, V=vagrant, ?=confirmation required Common Ostrich Red-billed Teal Dark Chanting-goshawk Great Crested Grebe V Northern Pintail R Western Marsh-harrier Black-necked Grebe R Garganey African Marsh-harrier Little Grebe Northern Shoveler V Montagu's Harrier European Storm-petrel V Cape Shoveler Pallid Harrier Great White Pelican Southern Pochard African Harrier-hawk Pink-backed Pelican African Pygmy-goose Osprey White-breasted Cormorant Comb Duck Peregrine Falcon Reed Cormorant Spur-winged Goose Lanner Falcon African Darter Maccoa Duck Eurasian Hobby Greater Frigatebird V Secretarybird African Hobby Grey Heron Egyptian Vulture V Sooty Falcon R Black-headed Heron Hooded Vulture Taita Falcon Goliath Heron Cape Vulture Red-necked Falcon Purple Heron White-backed Vulture Red-footed Falcon Great Egret Rüppell's Vulture V Amur Falcon Little Egret Lappet-faced Vulture Rock Kestrel Yellow-billed Egret White-headed Vulture Greater Kestrel Black Heron Black Kite Lesser Kestrel Slaty Egret R Black-shouldered Kite Dickinson's Kestrel Cattle Egret African Cuckoo Hawk Coqui Francolin Squacco Heron Bat Hawk Crested Francolin Malagasy Pond-heron R European Honey-buzzard Shelley's Francolin Green-backed Heron Verreaux's Eagle Red-billed Spurfowl Rufous-bellied Heron Tawny Eagle Natal Spurfowl Black-crowned Night-heron Steppe Eagle Red-necked Spurfowl White-backed Night-heron Lesser Spotted Eagle Swainson's Spurfowl Little Bittern Wahlberg's Eagle Common Quail Dwarf Bittern Booted Eagle Harlequin Quail Eurasian Bittern V African -

Simplified-ORL-2019-5.1-Final.Pdf

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part F: Simplified OSME Region List (SORL) version 5.1 August 2019. (Aligns with ORL 5.1 July 2019) The simplified OSME list of preferred English & scientific names of all taxa recorded in the OSME region derives from the formal OSME Region List (ORL); see www.osme.org. It is not a taxonomic authority, but is intended to be a useful quick reference. It may be helpful in preparing informal checklists or writing articles on birds of the region. The taxonomic sequence & the scientific names in the SORL largely follow the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) List at www.worldbirdnames.org. We have departed from this source when new research has revealed new understanding or when we have decided that other English names are more appropriate for the OSME Region. The English names in the SORL include many informal names as denoted thus '…' in the ORL. The SORL uses subspecific names where useful; eg where diagnosable populations appear to be approaching species status or are species whose subspecies might be elevated to full species (indicated by round brackets in scientific names); for now, we remain neutral on the precise status - species or subspecies - of such taxa. Future research may amend or contradict our presentation of the SORL; such changes will be incorporated in succeeding SORL versions. This checklist was devised and prepared by AbdulRahman al Sirhan, Steve Preddy and Mike Blair on behalf of OSME Council. Please address any queries to [email protected]. -

Bird Species I Have Seen World List

bird species I have seen U.K tally: 279 US tally: 393 Total world: 1,496 world list 1. Abyssinian ground hornbill 2. Abyssinian longclaw 3. Abyssinian white-eye 4. Acorn woodpecker 5. African black-headed oriole 6. African drongo 7. African fish-eagle 8. African harrier-hawk 9. African hawk-eagle 10. African mourning dove 11. African palm swift 12. African paradise flycatcher 13. African paradise monarch 14. African pied wagtail 15. African rook 16. African white-backed vulture 17. Agami heron 18. Alexandrine parakeet 19. Amazon kingfisher 20. American avocet 21. American bittern 22. American black duck 23. American cliff swallow 24. American coot 25. American crow 26. American dipper 27. American flamingo 28. American golden plover 29. American goldfinch 30. American kestrel 31. American mag 32. American oystercatcher 33. American pipit 34. American pygmy kingfisher 35. American redstart 36. American robin 37. American swallow-tailed kite 38. American tree sparrow 39. American white pelican 40. American wigeon 41. Ancient murrelet 42. Andean avocet 43. Andean condor 44. Andean flamingo 45. Andean gull 46. Andean negrito 47. Andean swift 48. Anhinga 49. Antillean crested hummingbird 50. Antillean euphonia 51. Antillean mango 52. Antillean nighthawk 53. Antillean palm-swift 54. Aplomado falcon 55. Arabian bustard 56. Arcadian flycatcher 57. Arctic redpoll 58. Arctic skua 59. Arctic tern 60. Armenian gull 61. Arrow-headed warbler 62. Ash-throated flycatcher 63. Ashy-headed goose 64. Ashy-headed laughing thrush (endemic) 65. Asian black bulbul 66. Asian openbill 67. Asian palm-swift 68. Asian paradise flycatcher 69. Asian woolly-necked stork 70. -

Mate Similarity in Foraging Kerguelen Shags: a Combined Bio-Logging and Stable Isotope Investigation

Mate similarity in foraging Kerguelen shags: a combined bio-logging and stable isotope investigation Citation: Camprasse, Elodie C. M., Cherel, Yves, Arnould, John P. Y., Hoskins, Andrew J., Bustamante, Paco and Bost, Charles-Andre 2017, Mate similarity in foraging Kerguelen shags: a combined bio-logging and stable isotope investigation, Marine ecology progress series, vol. 578, pp. 183-196. DOI: http://www.dx.doi.org/10.3354/meps12259 ©2017, The Authors Reproduced by Deakin University under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence Downloaded from DRO: http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30102992 DRO Deakin Research Online, Deakin University’s Research Repository Deakin University CRICOS Provider Code: 00113B Vol. 578: 183–196, 2017 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published August 31 https://doi.org/10.3354/meps12259 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Contribution to the Theme Section ‘Individual variability in seabird foraging and migration’ OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Mate similarity in foraging Kerguelen shags: a combined bio-logging and stable isotope investigation Elodie C. M. Camprasse1,*, Yves Cherel2, John P. Y. Arnould1, Andrew J. Hoskins3, Paco Bustamante4, Charles-André Bost2 1School of Life and Environmental Sciences (Burwood Campus), Deakin University, Geelong, 3220 Victoria, Australia 2Centre d’Etudes Biologique de Chizé (CEBC), UMR 7372 CNRS-Université de La Rochelle, 79360 Villiers-en-Bois, France 3CSIRO Land and Water, Canberra, 2601 Australian Capital Territory, Australia 4Littoral Environnement et Sociétés (LIENSs), UMR 7266 CNRS-Université de La Rochelle, 2 rue Olympe de Gouges, 17000 La Rochelle, France ABSTRACT: Similarity or dissimilarity between 2 individuals that have formed a pair to breed can occur in morphology, behaviour and diet.