Undemocratic Layout: Eight Methods of Accenting Images

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Batman: Year One by Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli Study Guide By

Graphic Novel Study Group Study Guides Batman: Year One By Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli Study guide by 1. In 1986, Miller and Mazzucchelli were charged with updating the classic character of Batman. DC Comics wanted to give the origin story “depth, complexity, a wider context.” Did Miller and Mazzucchelli succeed? 2. Why or why not? Give specific examples. 3. We meet Jimmy Gordon and Bruce Wayne at roughly the same moment in the novel. How are they portrayed differently, right from the beginning? Are these initial impressions in line with what we come to know about both characters later? 4. In both Jimmy and Bruce’s initial scenes, how are color and drawing style used to create an atmosphere, or to set them apart – their characters and their surroundings? Give a specific example for each. 5. Batman’s origin story is a familiar one to most readers. How do Miller and Mazzucchelli embroider the basic story? 6. What effect do their additions or subtractions have on your understanding of Bruce Wayne? 7. What are the major plots and subplots contained in the novel? 8. Where are the moments of high tension in the novel? 9. What happens directly before and after each one? How does the juxtaposition of low-tension and high-tension scenes or the repetition of high-tension scenes affect the pacing of the novel? 10. How have Jimmy Gordon and Bruce Wayne/Batman evolved over the course of the novel? How do we as readers understand this? Give specific examples. . -

Icons of Survival: Metahumanism As Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 169–196. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 20:32 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense In which I argue that superhero comics, the most maligned of nerd genres, theorize the transformation of ethics and politics necessary to the project of planetary defense. The figure of the “metahuman,” the human with superpowers and purpose, embodies the transfigured nerd whose defects—intellect, swarm-behavior, abnormality, flux, and love of machines—become virtues of survival in the twenty-first century. The conflict among capitalism, fascism, and communism, which drove the Cold War and its immediate aftermath, also drove the Golden and Silver Ages of Comics. In the era of planetary emergency, these forces reconfigure themselves as different versions of world-destruction. The metahuman also signifies going “beyond” these economic and political systems into orders that preserve democracy without destroying the biosphere. Therefore, the styles of metahuman figuration represent an appeal to tradition and a technique of transformation. I call these strategies the iconic style and metamorphic style. The iconic style, more typical of DC Comics, makes the hero an icon of virtue, and metahuman powers manifest as visible signs: the “S” of Superman, the tiara and golden lasso of Wonder Woman. -

English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada

Drawing on the Margins of History: English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada by Kevin Ziegler A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Kevin Ziegler 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This study analyzes the techniques that Canadian comics life writers develop to construct personal histories. I examine a broad selection of texts including graphic autobiography, biography, memoir, and diary in order to argue that writers and readers can, through these graphic narratives, engage with an eclectic and eccentric understanding of Canadian historical subjects. Contemporary Canadian comics are important for Canadian literature and life writing because they acknowledge the importance of contemporary urban and marginal subcultures and function as representations of people who occasionally experience economic scarcity. I focus on stories of “ordinary” people because their stories have often been excluded from accounts of Canadian public life and cultural history. Following the example of Barbara Godard, Heather Murray, and Roxanne Rimstead, I re- evaluate Canadian literatures by considering the importance of marginal literary products. Canadian comics authors rarely construct narratives about representative figures standing in place of and speaking for a broad community; instead, they create what Murray calls “history with a human face . the face of the daily, the ordinary” (“Literary History as Microhistory” 411). -

Girls in Graphic Novels

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2017 Girls in Graphic Novels: A Content Analysis of Selected Texts from YALSA's 2016 Great Graphic Novels for Teens List Tiffany Mumm Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Mumm, Tiffany, "Girls in Graphic Novels: A Content Analysis of Selected Texts from YALSA's 2016 Great Graphic Novels for Teens List" (2017). Masters Theses. 2860. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2860 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� EASTERNILLINOIS UNIVERSlTY Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. -

Dc Entertainment Feb20 0392 Joker 80Th Anniv 100 Page Super Spect #1 $9.99 Feb20 0393 Joker 80Th Anni

DC ENTERTAINMENT FEB20 0392 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 $9.99 FEB20 0393 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1940S ARTHUR ADAMS VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0394 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1950S DAVID FINCH VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0395 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1960S F MATTINA VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0396 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1970S JIM LEE VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0397 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1980S SEINKIEWICZ VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0398 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1990S G DELLOTTO VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0399 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 2000S LEE BERMEJO VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0400 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 2010S JOCK VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0401 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 BLANK VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0402 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 $9.99 FEB20 0403 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1940S ADAM HUGHES VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0404 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1950S TRAVIS CHAREST VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0405 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1960S STANLEY LAU VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0406 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1970S FRANK CHO VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0407 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1980S J SCOTT CAMPBELL VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0408 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1990S GABRIELLE DELL OTTO VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0409 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 2000S JIM LEE VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0410 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 2010S JEEHYUNG LEE VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 -

Download File

Words and Music... er, Images By Karen Green Friday April 3, 2009 09:00:00 am Our columnists are independent writers who choose subjects and write without editorial input from comiXology. The opinions expressed are the columnist's, and do not represent the opinion of comiXology. I know I've brought this up before, and lord knows it's been hashed over to hell-and-gone by everyone from bloggers to scholars to industry professionals, but let's all say it together one more time: comics tell a story via sequential art in which text and images are inextricably intertwined. (Well, except when there are no words. But let's not cloud the issue, eh?) Will Eisner put it succinctly, in his book Comics & Sequential Art: comics are "the arrangement of pictures or images and words to narrate a story or dramatize an idea." That seems pretty straightforward, right? Not such a challenging concept? I mean, that the words can't exist without the images or the images without the words? Not so difficult to comprehend? Not too arcane? And yet . In January of 2008, Groundwood Books released a graphic novel called Skim, written by Mariko Tamaki and drawn by Jillian Tamaki. The Tamakis are cousins from Canada, although Jillian now lives here in New York. In October, Skimwas nominated for the Governor General's Literary Award, a hugely prestigious Canadian prize (Skim was nominated in the Children's Literature category, which is grounds for an entirely different, and parenthetical, rant; see below). Or, to be more precise, Mariko Tamaki alone was nominated. -

Rationale for Magneto: Testament Brian Kelley

SANE journal: Sequential Art Narrative in Education Volume 1 Article 7 Issue 1 Comics in the Contact Zone 1-1-2010 Rationale For Magneto: Testament Brian Kelley Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sane Part of the American Literature Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Art Education Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Educational Psychology Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Higher Education Commons, Illustration Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kelley, Brian (2010) "Rationale For Magneto: Testament," SANE journal: Sequential Art Narrative in Education: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 7. Available at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sane/vol1/iss1/7 This Rationale is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in SANE journal: Sequential Art Narrative in Education by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Kelley: Rationale For Magneto: Testament 1:1_______________________________________r7 X-Men: Magneto Testament (2009) By Gregory Pak and Carmine Di Giandomenico Rationale by Brian Kelley Grade Level and Audience This graphic novel is recommended for middle and high school English and social studies classes. Plot Summary Before there was the complex X-Men villain Mangeto, there was Max Eisenhardt. As a boy, Max has a loving family: a father who tinkers with jewelry, an overprotective mother, a sickly sister, and an uncle determined to teach him how to be a ladies’ man. -

Graphic Novel Titles

Comics & Libraries : A No-Fear Graphic Novel Reader's Advisory Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives February 2017 Beginning Readers Series Toon Books Phonics Comics My First Graphic Novel School Age Titles • Babymouse – Jennifer & Matthew Holm • Squish – Jennifer & Matthew Holm School Age Titles – TV • Disney Fairies • Adventure Time • My Little Pony • Power Rangers • Winx Club • Pokemon • Avatar, the Last Airbender • Ben 10 School Age Titles Smile Giants Beware Bone : Out from Boneville Big Nate Out Loud Amulet The Babysitters Club Bird Boy Aw Yeah Comics Phoebe and Her Unicorn A Wrinkle in Time School Age – Non-Fiction Jay-Z, Hip Hop Icon Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain The Donner Party The Secret Lives of Plants Bud : the 1st Dog to Cross the United States Zombies and Forces and Motion School Age – Science Titles Graphic Library series Science Comics Popular Adaptations The Lightning Thief – Rick Riordan The Red Pyramid – Rick Riordan The Recruit – Robert Muchamore The Nature of Wonder – Frank Beddor The Graveyard Book – Neil Gaiman Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children – Ransom Riggs House of Night – P.C. Cast Vampire Academy – Richelle Mead Legend – Marie Lu Uglies – Scott Westerfeld Graphic Biographies Maus / Art Spiegelman Anne Frank : the Anne Frank House Authorized Graphic Biography Johnny Cash : I See a Darkness Peanut – Ayun Halliday and Paul Hope Persepolis / Marjane Satrapi Tomboy / Liz Prince My Friend Dahmer / Derf Backderf Yummy : The Last Days of a Southside Shorty -

Star Wars Art: Comics PDF Book

STAR WARS ART: COMICS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dennis O'Neil | 180 pages | 12 Oct 2011 | Abrams | 9781419700767 | English | New York, United States Star Wars Art: Comics PDF Book The Mandalorian. Mecklenburg received B. Non-necessary Non-necessary. I loved how they talked about "laser swords" and about how Luke looked "a little soft. Audiences first witnessed the lava-covered Mustafar back in Revenge of the Sith , but its presence in the overall Star Wars mythos has been much more widespread. Start the Conversation. Star Wars: The Force Awakens 1—6. Star Wars and sequential art share a long history: Star Wars debuted on the comic-book page in , when Marvel Comics began publishing a six-part adaptation of the first film, which morphed into a monthly comic book. All models feature two LCD screens. You may return the item to a Michaels store or by mail. Star Wars: Captain Phasma 1—4. Star Wars Adventures: Forces of Destiny 1—5 []. Most media released since then is considered part of the same canon, including comics. If you consider yourself a Jedi at the game of darts than this Star Wars Dartboard is for you. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. Leia 1 [] Reprints Star Wars Also at Amazon. And it? October 25, James Kelly Design 0. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Pin this product on Pinterest. Archived from the original on November 21, Now the third book […]. Archived from the original on May 7, Reproduction is clear and sharp. Star Wars Art: Comics Writer Return to Book Page. -

Growing up with Vertigo: British Writers, Dc, and the Maturation of American Comic Books

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ScholarWorks @ UVM GROWING UP WITH VERTIGO: BRITISH WRITERS, DC, AND THE MATURATION OF AMERICAN COMIC BOOKS A Thesis Presented by Derek A. Salisbury to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History May, 2013 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, specializing in History. Thesis Examination Committee: ______________________________________ Advisor Abigail McGowan, Ph.D ______________________________________ Melanie Gustafson, Ph.D ______________________________________ Chairperson Elizabeth Fenton, Ph.D ______________________________________ Dean, Graduate College Domenico Grasso, Ph.D March 22, 2013 Abstract At just under thirty years the serious academic study of American comic books is relatively young. Over the course of three decades most historians familiar with the medium have recognized that American comics, since becoming a mass-cultural product in 1939, have matured beyond their humble beginnings as a monthly publication for children. However, historians are not yet in agreement as to when the medium became mature. This thesis proposes that the medium’s maturity was cemented between 1985 and 2000, a much later point in time than existing texts postulate. The project involves the analysis of how an American mass medium, in this case the comic book, matured in the last two decades of the twentieth century. The goal is to show the interconnected relationships and factors that facilitated the maturation of the American sequential art, specifically a focus on a group of British writers working at DC Comics and Vertigo, an alternative imprint under the financial control of DC. -

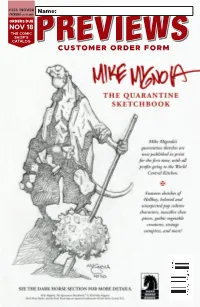

Customer Order Form

#386 | NOV20 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Nov20 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:23:12 AM Nov20 Ad DST Rogue.indd 1 10/8/2020 11:07:39 AM PREMIER COMICS HAHA #1 IMAGE COMICS 30 RAIN LIKE HAMMERS #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 CRIMSON FLOWER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 62 AVATAR: THE NEXT SHADOW #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 64 MARVEL ACTION: CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING 104 KING IN BLACK: BLACK KNIGHT #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-6 RED SONJA: THE SUPER POWERS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 126 ABBOTT: 1973 #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 158 Nov20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:24:32 AM COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE FEATURED ITEMS Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS I Breathed A Body #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS 1 Delicates TP l ONI PRESS l I Breathed A Body #1 AFTERSHOCK COMICS 1 The Cutting Edge: Devil’s Mirror #1 l TITAN COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS Knights of Heliopolis HC l TITAN COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Blade Runner 2029 #2 l TITAN COMICS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars Insider #200 l TITAN COMICS Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Comic Book Creator #25 l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Bloodshot #9 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Vagrant Queen Volume 2: A Planet Called Doom TP l VAULT COMICS Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC.