The Pennsylvania State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DAVID RYAN ADAMS C/O PAX-AM Hollywood CA 90028

DAVID RYAN ADAMS c/o PAX-AM Hollywood CA 90028 COMPETENCIES & SKILLS Design and construction of PAX-AM studios in Los Angeles to serve as home of self-owned-and-operated PAX-AM label and home base for all things PAX-AM. Securing of numerous Grammy nominations with zero wins as recently as Best Rock Album for eponymous 2014 LP and Best Rock Song for that record's "Gimme Something Good," including 2011's Ashes & Fire, and going back all the way to 2002 for Gold and "New York, New York" among others. Production of albums for Jenny Lewis, La Sera, Fall Out Boy, Willie Nelson, Jesse Malin, and collaborations with Norah Jones, America, Cowboy Junkies, Beth Orton and many others. RELEVANT EXPERIENCE October 2015 - First music guest on The Daily Show with Trevor Noah; Opened Jimmy Kimmel Live's week of shows airing from New York, playing (of course) "Welcome To New York" from 1989, the song for song interpretation of Taylor Swift's album of the same name. September 2015 - 1989 released to equal measures of confusion and acclaim: "Ryan Adams transforms Taylor Swift's 1989 into a melancholy masterpiece... decidedly free of irony or shtick" (AV Club); "There's nothing ironic or tossed off about Adams' interpretations. By stripping all 13 tracks of their pony-stomp synths and high-gloss studio sheen, he reveals the bones of what are essentially timeless, genre-less songs... brings two divergent artists together in smart, unexpected ways, and somehow manages to reveal the best of both of them" (Entertainment Weekly); "Adams's version of '1989' is more earnest and, in its way, sincere and sentimental than the original" (The New Yorker); "the universality of great songwriting shines through" (Billboard). -

The Gamecaucus Opinion

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons January 2008 1-17-2008 The aiD ly Gamecock, THURSDAY, JANUARY 17, 2008 University of South Carolina, Office oftude S nt Media Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/gamecock_2008_jan Recommended Citation University of South Carolina, Office of Student Media, "The aiD ly Gamecock, THURSDAY, JANUARY 17, 2008" (2008). January. 9. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/gamecock_2008_jan/9 This Newspaper is brought to you by the 2008 at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in January by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Gamecaucus Opinion..................6 Puzzles....................9 Comics....................9 The Daily Gamecock endorses Texas Rep. Ron Paul for Horoscopes..............9 Classifi ed................12 Republican presidential nomination See page 6 dailygamecock.com THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA THURSDAY, JANUARY 17, 2008 VOL. 101, NO. 74 ● SINCE 1908 ROMNEY VISITS CAMPUS Fresh from win in Mich., former governor shifts Here’s a glimpse at focus to Palmetto state the GOP candidates in S.C. primary Halley Nani THE DAILY GAMECOCK Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz. Former Massachusetts Age: 71 Current job: U.S. Gov. Mitt Romney spoke senator from Arizona on family, military and War in Iraq: He opposes an economic issues to students immediate troop withdrawal and supporters Wednesday and opposes a timetable for night in the Russell House withdrawal. Ballroom. Abortion: He opposes “It was a big night last abortion rights except in night in Michigan,” Romney cases of rape, incest or to said. “Only a week ago we protect the life of the mother were down in polls. -

THE LIST Is : A) the Result of a Lifelong Love of - and Dedication to - Rock and Roll

over THE LIST is : a) The result of a lifelong love of - and dedication to - rock and roll. b) A latest stab at The Great American Bar/Party Band. c) A tip-of-the-hat to favorite rock bands and singer-songwriters (with sidetracks into New Wave, 70's One-Hit Wonders, weird Alternative gems and new faves like Ryan Adams... d.) All of the above. THE LIST Answer: d. At this point, there are almost 300 songs on THE LIST. THE LIST Directions: Find something you like, shout out a number - and we'll do our best. THE LIST band is: Tim Brickley: guitar, piano, vocals, Larry DeMyer: lead guitar, vocals Matt Price: drums Tom Waldo: bass, vocals THE LIST: 1 A Long December COUNTING CROWS 2 A Song For You LEON RUSSELL 3 Across The Universe BEATLES 4 After The Goldrush NEIL YOUNG 5 Ain’t No New Girls Around BRICKLEY/J. SCOT SHEETS 6 Ain’t Too Proud To Beg TEMPTATIONS 7 Alison ELVIS COSTELLO 8 All Along The Watchtower DYLAN/HENDRIX/DMB 9 All I Really Want To Do DYLAN 10 All I Want Is You U2 11 All Over Now ROLLING STONES 12 All You Need Is Love BEATLES 13 Allentown BILLY JOEL 14 America SIMON AND GARFUNKEL 15 American Pie DON McCLEAN 16 Amoreena ELTON JOHN 17 Androgynous THE REPLACEMENTS 18 Angel Of Harlem U2 19 Any Major Dude STEELY DAN 20 Baby, It’s You BEATLES 21 Babylon DAVID GRAY 22 Back In The USSR BEATLES 23 Beautiful Soul DANNY FLANIGAN 24 Because The Night PATTI SMITH/SPRINGSTEEN 25 Beginnings CHICAGO 26 Behind Blue Eyes THE WHO 27 Bennie and the Jets ELTON JOHN 28 Best Of My Love EAGLES 29 Bird On A Wire LEONARD COHEN 30 Blackbird BEATLES 31 Blame It On Cain ELVIS COSTELLO 32 Bluebird PAUL McCARTNEY 33 Brandy LOOKING GLASS 34 Bright Baby Blues JACKSON BROWNE 35 Brown-Eyed Girl VAN MORRISON 36 Candle In The Wind ELTON JOHN 37 Carmelita WARREN ZEVON 38 Carolina In My Mind JAMES TAYLOR 39 Casey Jones GRATEFUL DEAD 40 Centerfold J. -

Karaoke with a Message – August 16, 2019 – 8:30PM

Another Protest Song: Karaoke with a Message – August 16, 2019 – 8:30PM a project of Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere for SOMA Summer 2019 at La Morenita Canta Bar (Puente de la Morena 50, 11870 Ciudad de México, MX) karaoke provided by La Morenita Canta Bar songbook edited by Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere ( ) 18840 (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash 10274 (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & Diamonds 00005 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 17636 (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 15910 (I Want To) Thank You Freddie Jackson 05545 (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees 06305 (It's) A Beautiful Mornin' Rascals 19116 (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon 15128 (Keep Feeling) Fascination Human League 04132 (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran 05241 (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding 17305 (Taking My) Life Away Default 15437 (Who Says) You Can't Have It All Alan Jackson # 07630 18 'til I Die Bryan Adams 20759 1994 Jason Aldean 03370 1999 Prince 07147 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer 18961 21 Guns Green Day 004-m 21st Century Digital Boy Bad Religion 08057 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 00714 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band 01379 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 14375 3 Strange Days School Of Fish 08711 4 Minutes Madonna 08867 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 09981 4 Minutes Avant 18883 5 Miles To Empty Brownstone 13317 500 Miles Peter Paul & Mary 00082 59th Street Bridge Song Simon & Garfunkel 00384 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 08937 99 Luftballons Nena 03637 99 Problems Jay-Z 03855 99 Red Balloons Nena 22405 1-800-273-8255 -

Edward Sharpe & the Magnetic Zerosна

Various Artists: Edward Sharpe & The Magnetic Zeros Home Juno Soundtrack Anyone Else but You, All i want is You Frankie Valli Cant take my eyes off of you Tangerine Kitty Dumb Ways to Die Foster the People Foster the People Any Winehouse Back To Black Frank Fly me to the Moon Ross Ryan I am Pegasus Lyale Lovett If i Had a Boat Phil Philips Sea of Love Stereophonics Dakota Queens of the StoneageMake it Witchu Magnetic Fields/Peter Gabriel The Book of Love Mumford & SonsLittle Lion Man, The Cave Beach BoysGod Only Knows BeckGuess I’m Doin’ Fine Nobody's Fault But Mine Kylie Minogue Can’t get you out of my head Portishead Glorybox Jimmy Buffet Come Monday someone – House Of the Rising Sun Chris Isaac – Wicked Game The Stranglers – Golden Brown Alex LloydAmazing Old Man River Wedding Song Jason Mraz – I’m Yours The Killers – Somebody Told Me Massive Attack Teardrop Tegan & Sarah – Back In Your Head Bobby Gentry Ode To Billy Jo John WilliamsonTrue Blue GershwinSummertime Sarah BlaskoPerfect Now The Eels – Mr E’s beautiful blues i Like Birds The Triffids – Wide Open Road ,,Bury me Deep in Love Icehouse Great Southern Land John Sebastian – Welcome Back Kotter Glen Campbell – Gentle On Mind Prince Kiss The Shins New Slang Travis Sing Amy Winehouse Back to Black Lou Reed Perfect day Little Heroes One perfect day Bob Marley – Redemption Song Stir it Up Harry Chapin – Cats In the Cradle Hair Where do I go Jackson Browne Song 4 Adam John Butler Trio Peaches and Cream Judie Tzuke – Stay with Me Dawn Rocky Horror – Sweet Transvestite Gordon Lightfoot – Sundown The Verve – Drugs Don’t Work, Song 4 the Lovers Ringo – Photogragh Peter Sarsdendt – Where You Go To My Lovely Jackson 5 – I Want You Back Nirvana – Something in the Way Kinks – Sunny Afternoon Daniel Lanoi The Maker Peter Byorn & John Youngfolk Madonna Crazy 4 you. -

Its Brief, Lucky Says That Defense Preclusion Is Inefficient and Unfair

No. 18-1086 In the Supreme Court of the United States Lucky Brand Dungarees, et al., Petitioners, v. Marcel Fashion Group, Inc., Respondent. On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT Eugene R. Fidell Michael B. Kimberly Yale Law School Counsel of Record Supreme Court Clinic Paul W. Hughes 127 Wall Street Andrew A. Lyons-Berg New Haven, CT 06511 McDermott Will & Emery LLP 500 North Capitol Street NW Louis R. Gigliotti Washington, DC 20001 Louis R. Gigliotti, PA (202) 756-8000 1605 Dewey Street [email protected] Hollywood, FL 33020 Robert L. Greener Law Office of Robert L. Greener P.C. 112 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10016 Counsel for Respondent TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................. 1 Statement .................................................................... 6 A. The 2001 lawsuit and settlement .................. 6 B. Lucky’s continued infringement of Marcel’s mark, and the 2005 suit .................. 6 C. Lucky’s identical post-judgment infringement, and the present suit ............. 11 Summary of Argument .............................................. 16 Argument ................................................................... 20 I. A defendant who loses in one lawsuit may not raise in a subsequent lawsuit involving the same cause of action a defense that was available in the first lawsuit .............................. 20 A. Res judicata promotes repose and the finality of judgments, discourages repetitive litigation, and preserves judicial resources ......................................... 22 B. Res judicata precludes not only claims, but also defenses .......................................... 24 1. Defense preclusion generally bars a former defendant from converting a neglected defense into a claim .............. 26 2. Defense preclusion also bars a defendant from raising in a second action a defense omitted from a first action addressing the same claims ...... -

Jim Darvidis - Song List

Jim Darvidis - Song List 3AM Matchbox 20 Aint No Sunshine Bill Withers Allstar Smash Mouth American Idiot Greenday American Pie Don McLean April Sun in Cuba Dragon Are you Gonna be my Girl Jet At Last Etta James Baby did a bad bad thing Chris Issac Beautiful people Aussie crawl Better be home Soon Crowded House Better Man Robbie Williams Better Man Pearl Jam Better Together Jack Johnson Black fingernails, Red wine Eskimo Joe Blackbird Beatles Blister in the Sun Violent Femmes Born to run Bruce Springsteen Brandy, you’re a fine girl Looking Glass Bright side of the road Van Morrisson Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrisson Build me up Buttercup Foundations Can't get enough of you Baby Smash Mouth Can't Help Falling in Love Elvis Presley Can't take my eyes off you Andy Williams Catch My Disease Ben Lee Cats in the Cradle Harry Chapin Centrefold J Geils Band Cherry Bomb John Mellancamp Come on Eileen Dexys midnight Runners Concrete and Clay Martin Plaza Cool Change LRB Copperhead Road Steve Earle Cracklin’ Rosie Neil Diamond Crazy Little Thing Called Love Queen Crunchy Granola Suite Neil Diamond Dakota Stereophonics Dancing in the Moonlight Top Loader Dancing Queen Abba Desperado Eagles Devil Inside Inxs Dizzy Vic Reeves/Tommy Roe Domino Van Morrisson Don't be Cruel Elvis Presley Down Under Men at Work Dreadlock holiday 10CC Drift Away Dobie Gray Drugs Don't Work The Verve Easy Faith no more Eight Days a Week Beatles End of the Line Travelling Willburies Evergreen Barbara Streisand Every Morning Sugar Ray Everybody’s Talking Harry Nilson Everything -

Luck Feelings, Luck Beliefs, and Decision Making

Luck Feelings, Luck Beliefs, and Decision Making Harold W. Willaby Psychology University of Sydney A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) 2012 October 1. Reviewer: Anonymous 2. Reviewer: Michael J. A. Wohl 3. Reviewer: Peter R. Darke Signature from head of PhD committee: ii Abstract Luck feelings have long been thought to influence decision-making involv- ing risk. Previous research has established the importance of prior out- comes, luck beliefs, and counterfactual thinking in the generation of luck feelings, but there has been no comprehensive demonstration of this system of variables that impinge on luck feelings. Moreover, the actual relationship of luck feelings and risky choice has not been directly tested. Addressing these gaps, results from five studies are presented in this thesis. Empirical work begins with an extensive validation exercise of an existing 22-item luck beliefs scale. Those 22 items are refined to a 16-item scale, comprising four luck belief dimensions that inter-relate in a compelling structural ar- rangement. Insights from this exercise, and a subset of the items are used throughout the remainder of the thesis. Results from two studies contra- dicted the counterfactual closeness hypothesis, the most prominent theory in the psychology of luck, which holds that counterfactual thinking is essen- tial for generating lucky feelings. However, one study found that affect and luck feelings are not unitary, as evidenced by a weak form of double disso- ciation of affect and lucky feelings from overestimation and overplacement. Another study found lucky and unlucky feelings to be distinct. The effects of lucky feelings and unlucky feelings on risky choice differ by the nature of a prior outcome. -

FATIMA WASHINGTON on Songwriting, an Hour Each Day Practicing Guitar and an Hour Or Bowie’S Influence Mellows MTH out a Little on This Record, More Each Day Singing

-----------------------------------------Spins --------------------------------------- Wooden Nickel Ryan Adams CD of the Week Ashes & Fire BACKTRACKS Now a sober man with a Hol- Mott the Hoople lywood wife, a Hollywood house and All the Young Dudes (1972) his own record label, Pax Am, Ryan Adams has released the first record When Mott the Hoople members of his second act, a mellow and warm were trying to figure out the direction singer/songwriter effort called Ashes of the band (and its fifth record), along & Fire. The two things you’re bound came glam-rocker David Bowie. Bowie to hear about this record, if you’re the penned the title track and produced an investigative type, is that: (1) The record is quite mellow and feels album that would save the careers of Ian like something of a brother to Neil Young’s Harvest and After the Hunter and the rest of MTH. It would become one of the most Goldrush; and 2) Adams has become, maybe above all else, an in- recognizable songs in rock n’ roll. credible vocalist. Opening with Lou Reed’s “Sweet Jane,” MTH cover this clas- In a 2001 interview, following the release of his make-or-break sic with a happier vibe and a progressive, almost Calypso beat. $9.99 sophomore solo release, Gold, Adams spoke about his then-strict “Momma’s Little Jewel” has a fat piano arrangement and some routine, where he forced himself to spend an hour each day working horns and “Sucker” has that early, glam-Euro rock of the 1970s. FATIMA WASHINGTON on songwriting, an hour each day practicing guitar and an hour or Bowie’s influence mellows MTH out a little on this record, more each day singing. -

5Th Dimension

5th Dimension - Aquarius - Let The Sunshine In 5th Dimension - Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 5th Dimension - My Girl 5th Dimension - One Less Bell To Answer 5th Dimension - Stoned Cold Picnic 5th Dimension - Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension - Up, Up & Away 5th Dimension - Wedding Bell Blues 702 - Where My Girls At 7th Heaven - Sing 8 Stops 7 - Question Everything 911 - A Little Bit More 911 - All I Want Is You 911 - Baby Come To Me 911 - How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 - Little Bit More 911 - More Than A Woman 911 - Party People (Friday Night) 911 - Private Number 98 Degrees - Because Of You 98 Degrees - Give Me Just One Night 98 Degrees - Hardest Thing 98 Degrees - I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees - Invisible Man 98 Degrees - My Everything 98 Degrees - She's Out Of My Life 98 Degrees - The Way You Want Me To 98 Degrees - This Gift 98 Degrees - True To Your Heart 98 Degrees - Way You Want Me To A Day To Remember - All Signs Point To Lauderdale A Day To Remember - It's Complicated A Flock Of Seagulls - Wishing A Gardner - Life Less Ordinary A Ha - (Seemingly) Nonstop July A Ha - And You Tell Me A Ha - Blue Sky A Ha - Cry Wolf A Ha - Crying In The Rain A Ha - Dark Is The Night For All A Ha - Everyone Can Say They're Sorry A Ha - Here I Stand And Face Rain A Ha - Hunting High And Low A Ha - Living A Boy's Adventure Tale A Ha - Maybe Maybe A Ha - Rolling Thunder A Ha - Scoundrel Days A Ha - Stay On These Roads A Ha - Summer Moved On A Ha - Sun Always Shines On TV A Ha - Take On Me A Ha - There's Never A Forever Thing A Ha - Touchy A Ha - Train Of Thought A Ha - Waiting For Her A Ha - We're Looking For The Whales A Ha - You Are The One A Hammond - Never Rains In Southern California A Perfect Circle - Hollow A Perfect Circle - Weak And Powerless A R Rahman & Pussycat Dol - Jai Ho (You Are My Destiney) A T B - Killer A Taste Of Honey - Sukiyaki A Teens - Bouncing Off The Ceiling A Teens - Halfway Around The World A Teens - Land Of Make Believe A.L Ray - Baby Got Back A.R. -

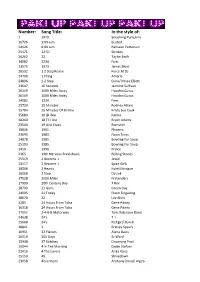

Song Title: in the Style Of: 1 1979

Number: Song Title: In the style of: 1 1979.. Smashing Pumpkins 16726 3:00 a.m. Busted 24126 6:00 a.m. Rahsaan Patterson 25171 12:51 Strokes 26262 22 Taylor Swift 14082 1234 Fiest 13575 1973 James Blunt 26532 1 2 Step Remix Force M Ds 24700 1 Thing Amerie 24896 1.2 Step Ciara/ Missy Elliott 23647 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan 26149 1000 Miles Away Hoodoo Gurus 26149 1000 Miles Away Hoodoo Gurus 14082 1234.. Fiest 25720 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins 15784 15 Minutes Of Shame Kristy Lee Cook 15689 16 @ War Karina 18260 18 Til I Die Bryan Adams 23540 19 And Crazy Bomshel 18846 1901.. Phoenix 23643 1983.. Neon Trees 24878 1985.. Bowling For Soup 25193 1985.. Bowling For Soup 1419 1999.. Prince 2165 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones 25519 2 Become 1 Jewel 13117 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 18506 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue 16068 2 Step Dj Unk 17028 2000 Miles Pretenders 17999 20th Century Boy T Rex 18730 21 Guns Green Day 24005 21 Today Piano Singalong 18670 22.. Lily Allen 3285 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 16318 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 17057 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 24638 24's T. I. 25660 24's Richgirl/ Bun B 18841 3.. Britney Spears 10951 32 Flavors Alana Davis 26519 365 Days Zz Ward 15938 37 Stitches Drowning Pool 15044 4 In The Morning Gwen Stefani 21410 4 The Lovers Arika Kane 25150 45.. Shinedown 23058 4evermore Anthony David/ Algeb 26356 4th Of July Brian McKnight 16144 5 Colours In Her Hair Mc Fly 1594 5.6.7.8 Steps 25883 50 Ways To Say Goodbye Train 16207 5-4-3-2-1 Manfred Mann 3809 57 Chevrolet Billie Jo Spears 18828 59th Street Bridge Song( No Harmony) Simon & Garfunkel 1694 59th Street Bridge Song( W Harmony) Simon & Garfunkel 16383 6345-789 Blues Brothers 11153 800 Pound Jesus Sawyer Brown 10385 80's Ladies K.t. -

Ryan Adams Jacksonville Mp3, Flac, Wma

Ryan Adams Jacksonville mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Jacksonville Country: US Released: 2014 Style: Alternative Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1467 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1441 mb WMA version RAR size: 1954 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 663 Other Formats: RA VOX AA AAC AC3 MOD FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits Jacksonville Acoustic Guitar, Backing Vocals – Mike ViolaDrums – Marshall VoreEngineer, Mixed By – A Charlie StavishGuitar, Bass, Vocals – Ryan AdamsRecorded By [Additional Recording] – David Labrel I Keep Running B1 Performer [Ryan Adams Played Everything] – Ryan Adams Walkedypants B2 Bass – Tal WilkenfeldDrums – Jeremy StaceyEngineer, Mixed By – Charlie Stavish, David LabrelGuitar, Vocals – Ryan AdamsPiano – Benmont Tench Companies, etc. Distributed By – Caroline Distribution Manufactured By – Caroline Distribution Phonographic Copyright (p) – Pax Americana Record Company Copyright (c) – Pax Americana Record Company Pressed By – United Record Pressing Engineered At – Paxam Studios Mixed At – Paxam Studios Credits Design – Andy West Design* Photography By – Ryan Adams Producer – Mike Viola, Ryan Adams Notes Blue Vinyl variant started to appear March/April 2017 All songs exclusive to this release. Made in U.S.A. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 602537919857 Matrix / Runout (A-Side etched): BOD2124221A ⓤ BG Matrix / Runout (B-Side etched): BOD2124221B ⓤ BG Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Pax Americana PAX-AM 040, Ryan Jacksonville Record Company, PAX-AM 040, US 2014 2537919857