EXPLORING the BRAND IDENTITY CREATION of FEMALE ATHLETES: the CASE of JENNIE FINCH and CAT OSTERMAN a Dissertation by JAMI NICO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010-Softbl-Mg-Sec4.Pdf

O P P O N E N T S PACIFIC-10 CONFERENCE The Pacifi c-10 Conference continues to uphold its tradition as the “Conference of Champions” ®, claiming an incredible 166 NCAA team titles PAC-10 CONFERENCE STAFF DIRECTORY over the past 19 years, including 11 in 2008-09, averaging nearly nine championships per academic year. Even more impressive has been the breadth of the Pac-10’s success, with championships coming in 26 different men’s and women’s sports. The Pac-10 has led the nation in NCAA 1350 Treat Boulevard, Suite 500 Walnut Creek, CA 94597-8853 Championships in 43 of the last 49 years and fi nished second fi ve times. Phone: (925) 932-4411 • Fax: (925) 932-4601 Spanning nearly a century of outstanding athletics achievements, the Pac-10 has captured 380 NCAA titles (261 men’s, 119 women’s), far outdistancing the runner-up Big Ten Conference’s 222 titles. COMMISSIONER The Conference’s reputation is further proven in the annual Learfi eld Sports Directors’ Cup competition, the prestigious award that honors Larry Scott the best overall collegiate athletics programs in the country. STANFORD won its 15th-consecutive Directors’ Cup in 2008-09, continuing its ASSOCIATE COMMISSIONER remarkable run. Eight of the top 25 Division I programs were Pac-10 member institutions: No. 1 STANFORD, No. 4 USC, No. 7 CALIFORNIA, No. ADMINISTRATION & WOMEN’S BASKETBALL ADMIN 11 WASHINGTON, No. 12 ARIZONA STATE, No. 16 UCLA, No. 22 OREGON and No. 24 ARIZONA. The Pac-10 landed three programs in the top-10, Christine Hoyles one more than the second-place ACC, Big Ten and SEC (2). -

The Athens Olympics

SJMN Operator: NN / Job name: XXXX0045-0001 / Description: Zone:MO Edition: Revised, date and time: 02/04/58, 21:16 Typeset, date and time: 08/04/04, 01:31 080804MOOL0U001 / Typesetter: IIIOUT / TCP: #1 / Queue entry: #0989 CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK 8/8/2004 MO 1 SECTION OL | SUNDAY, AUGUST 8, 2004 .... THE ATHENS OLYMPICS THE GOLDEN STATE PORTRAITS No one brings home Olympic medals VIEWERS’ GUIDE An up-close look What to watch at Bay Area Olympians like Californians. Here’s why. and when to watch it PAGES 2-16 STORIES, PAGES 3-7 SECTION T, BEHIND THIS SECTION .... JIM GENSHEIMER — MERCURY NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS SJMN Operator: NN / Job name: XXXX0252-0002 / Description: Zone:MO Edition: Revised, date and time: 05/10/04, 17:52 Typeset, date and time: 08/04/04, 00:00 080804MOOL0U002 / Typesetter: IIIOUT / TCP: #1 / Queue entry: #0918 CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK 8/8/2004 MO 2 2 WWW.MERCURYNEWS.COM SAN JOSE MERCURY NEWS SUNDAY, AUGUST 8, 2004 The Athens Olympics Welcome to our coverage of the About the Olympic portraits 2004 Games Throughout these pages you will find a se- ‘‘Most Olympic athletes toil away in obscuri- ries of stunning portraits taken over the past ty with little compensation in the form of mon- The Summer Olympics are some- four months by the Mercury News’ Jim Gens- ey or acclaim. Why do they do it? Most will tell thing special to the Bay Area, where swimmers, runners and cyclists are heimer, who has photographed Olympians to you they do it for the love of their sport; for the as much a part of the culture as foot- ball, baseball and basketball players. -

Series Records

SERIES RECORDS NCAA BATTING LEADERS Batting Avg. Slugging Pct. On base pct. 1. Arizona 95 .394 1. UCLA 10 .735 1. UCLA 10 .467 2. Arizona 96 .370 2. Florida 11 .580 2. Arizona 95 .463 3. UCLA 10 .368 3. UCLA 19 .574 3. Arizona St. 11 .452 4. Washington 96 .351 4. Arizona St.11 .559 4. Arizona 96 .443 5. Arizona St. 11 .338 5. Florida 14 .551 5. Florida 11 .433 Runs Scored Hits Runs Batted In 1. Florida 11 47 1. Arizona 10 57 1. Florida 11 45 UCLA 10 47 UCLA 10 57 2. UCLA 10 44 3. Florida St. 18 39 3. Arizona 07 55 3. Florida St. 18 37 4. UCLA 19 37 4. Florida 11 54 4. Auburn 16 34 5. Auburn 16 36 5. Florida St. 18 53 5. Arizona St. 11 32 Arizona 10 36 UCLA 19 32 Triples Doubles 1. Cal St. Fullerton 86 4 Home Runs 1. UCLA 10 15 Oklahoma 13 4 1. UCLA 10 14 2. Florida St.18 12 3. Oklahoma 12 3 Florida 11 14 3. Florida 14 10 4. 3 tied at 2 3. UCLA 19 12 4. 4 tied at 8 4. Florida St. 18 10 Total Plate Appearances 5. Arizona St. 11 9 Total Bases 1. Texas A&M 84 275 1. UCLA 10 114 2. Arizona 07 246 At Bats 2. Florida 11 101 3. California03 226 1. Texas A&M 84 251 3. Florida St. 18 95 4. Michigan 05 221 2. Arizona 07 214 4. UCLA 19 89 5. -

Softball Award Winners

Softball Award Winners Division I First-Team All-Americans by School ....................................................... 2 Division I First-Team All-America (1984-2014) .................................................. 3 Division II First-Team All-Americans by School ....................................................... 5 Division II First-Team All-America (1986-2014) .................................................. 6 Division III First-Team All-Americans by School ....................................................... 8 Division III First-Team All-America (1982-2014) .................................................. 9 National Award Winners ...........................12 2 NCAA 2015 SOFTBALL AwaRDS RECORDS THROUGH 2014 All-America Teams Chosen by the National Fastpitch Coaches Association ARIZONA ST. (19) COLORADO ST. (1) 06— Jenna Hall 13—Amber Freeman 97— Sarah Fredstrom ILL.-CHICAGO (1) Division I 12— Katelyn Boyd Alix Johnson CREIGHTON (1) 05— Cameron Astiazaran All-Americans 11— Katelyn Boyd 88— Jody Schwartz INDIANA (2) by College Kaylyn Castillo DePAUL (3) 86— Karleen Moore Dallas Escobedo 03— Lindsay Chouinard Amy Unterbrink 10— Katelyn Boyd 99— Liza Brown (First-Team Selections) 09— Kaitlin Cochran IOWA (4) 08— Katie Burkhart 95— Missy Nowak 01— Kristi Hanks ALABAMA (17) Kaitlin Cochran FLORIDA (10) 97— Debbie Bilbao 14— Hayley McCleney 07— Katie Burkhart 14— Kelsey Stewart 91— Diane Pohl Jaclyn Traina Kaitlin Cochran 13— Lauren Haeger 90— Diane Pohl 13— Kayla Braud 06— Kaitlin Cochran Hannah Rogers KANSAS (5) 12— Jackie Traina 02— Phelan Wright 12— Michelle Moultrie 11— Kayla Braud 99— Erica Beach 11— Kelsey Bruder 92— Camille Spitaleri Kelsi Dunne 97— Lisa Dacquisto Megan Bush 91— Camille Spitaleri Jackie Traina 93— Lisa Dacquisto Brittany Schutte 90— Camille Spitaleri 09— Kelsi Dunne 92— Rachel Brown 09— Stacey Nelson 87— Sheila Connolly Charlotte Morgan 86— Kathy Escarcega 08— Alexandra Gardiner 86— Tracy Bunge 08— Kelley Montalvo Stacey Nelson LA.-LAFAYETTE (14) Charlotte Morgan AUBURN (1) 14— Branndi Melero FLORIDA ST. -

Tight Race for Village Board

Dining Out? See What Town Hall Held In MP Previewing Area's ******CRLOT 0041A**C071 P'Zazz Has To Offer! On Legal Marijuana Varsity Softball Teams MT PROSPECT PUBLIC LIBRARY 10 S EMERSON ST STE 1 Special section Page 3A Page 8AA MT PROSPECT, IL 60056-3295 0000115 MOUNT PROSPECT JOURNAL Vol. 89 No. 14 Journal & Topics Media Group I journal-topics.com I Wednesday, April 3, 2019 I S1 ELECTION RESULTS Tight Race For Village Board VILLAGE BOARD MT. PROSPECT PARK BOARD DIST. 57 SCHOOL BOARD DIST. 26 REFERENDUM 30 of 34 precincts; vote for 3 28 of 35 precincts; vote for 4 19 of 21 precincts; vote for 3 8 of 10 precincts; Issue bonds? Richard Rogers 2,293 .0 Lisa Tenuta 2,316 Jennifer Kobus 1,579 Yes 648 Colleen E. Saccotelli 2,658 David V. Perns 1,614 Rachael Rothrauff 1,532 .0 No 861 Paul Wm. Hoefert 2,655 . Bill Klicka 1,757 .0 Kimberly Fay 1,506 Yulia Bjekic 2,274 .0 Michael Murphy 2,399 Kristine A. O'Sullivan 1,323 Augie Filippone 1,277 %/Timothy J. Doherty 2,196 UNOFFICIAL RESULTS AS OF 10:45 PM. TUESDAY, APRIL 2 =PROJECTED WINNER I TURN TO WWWJOURNAL-TOPICS.COM FOR MORE LOCAL ELECTION COVERAGE! By CAROLINE FREER Richard Rogers in a fight for the third Journal & Topics Reporter trustee seat on the board. Bjekic had 20.45 percent of counted votes to Rogers With six candidates fighting for three 20.16 percent. seats on the Mount Prospect Village Then at 10 p.m. things started turning Board, two incumbents look sure to bein Rogers' direction as 30 precincts re- returning. -

October 17, 2019 University of California, Santa Barbara U.S

DAILY NEXUS THURSDAY, OCTOBER 17, 2019 www.dailynexus.com UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA U.S. Women’s Soccer Captains Speak on Gender Equality, World Cup Success at Arlington Theater Barbara Soccer Club and American Youth Soccer Organization (AYSO). “It’s weird seeing her in person and not on my phone screen,” Reese Termond, a 17-year-old who attended the soccer clinic, said after seeing Rapinoe. “She’s actually human and not a robot that dribbles through people and scores goals.” Both on and off the field, Rapinoe was relaxed, personably cracking jokes as she gave advice and answered questions. Morgan was unable to assist at the clinic due to a knee injury but came later to the event to speak to the younger players, urging them to believe in themselves and their abilities. “Did I think that this would actually happen? I’m not sure. But I had the dream when I was 7, my mom believed in me, my family believed in me and that encouragement helped me become who I am today,” Morgan said after being asked by a player at the clinic if she always believed she would play professional soccer. Morgan and Rapinoe’s personal and professional growth was also discussed in-depth at their evening talk. Moderator Catherine Remak, from the radio station K-LITE, brought up their experiences playing high school and college soccer; Rapinoe played for the University of Portland and Morgan for UC Berkeley. Rapinoe joked about her experiences getting “walloped” as a high school player who was “never on a winning team.” But she admitted that the experience of losing led to growth, stating how “even at this level, we’ve had some really tough losses in our career and you can’t let that define you.” Both captains discussed some of the difficult defeats they’ve endured, referencing their loss to Japan at the 2011 FIFA World Cup on a penalty shootout in overtime as an example. -

2017-FSU-Softball-Media-Guide.Pdf

NINE WOMEN’S COLLEGE WORLD SERIES APPEARANCES • 14 ACC CHAMPIONSHIPS TABLE OF CONTENTS 2017 Florida State Softball Table of Contents .....................................1 2016 Review This is FSU: Tradition ...............................2 2016 Season In Review .................44-45 This is FSU: Community/Academics ..3 2016 Final Statistics .............................. 46 This is FSU: Facilities ................................4 2016 ACC Standings and Results .... 47 This is FSU: Dugout Club .......................5 2016 Team Game Highs ...................... 48 #FSACC (Five Core Values) ....................6 2016 Individual Game Highs ............ 49 2014 WCWS ...............................................7 2016 Game-By-Game Results .......... 50 2016 WCWS ...............................................8 Last Time It Happened ........................ 51 2016 Softball Quick Facts ......................9 2016 Roster.............................................. 10 History of the Program Play For Those Who Can’t.................. 11 Hall of Fame & All-Americans .......... 52 Honors and Awards ........................53-56 Student-Athletes All-Time Letterwinners ........................ 57 Jessica Burroughs ............................12-13 Pro & International Players ............... 58 Sydney Broderick .............................14-15 1981 & 1982 National Champions .. 59 Ellie Cooper .......................................16-17 Dr. JoAnne Graf ...................................... 60 Alex Powers .......................................18-19 -

Updated Record Book 9 25 07.Pmd

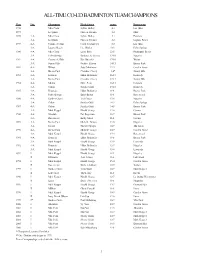

ALL-TIME CO-ED BADMINTON TEAM CHAMPIONS Year Div. Champion Head Coach Score Runner-up 1976 Mira Costa Sylvia Holley 4-1 Los Altos 1977 La Quinta Floreen Fricioni 3-2 Muir 1978 4-A Mira Costa Sylvia Holley 4-1 Estancia 3-A La Quinta Floreen Fricioni 3-2 Laguna Beach 1979 4-A Corona del Mar Carol Stockmeyer 8-5 Los Altos 3-A Laguna Beach Dee Brislen 10-3 Palm Springs 1980 4-A Mira Costa Larry Bark 22-5 Huntington Beach 3-A Palm Springs Barbara Jo Graves 17-10 Nogales 1981 4-A Corona del Mar Kim Duessler 17-10 Walnut 3-A Sunny Hills Pauline Eliason 14-13 Buena Park 1982 4-A Walnut Judy Manthorne 22-5 Garden Grove 3-A Buena Park Claudine Casey 1-0* Sunny Hills 1983 4-A Estancia Lillian Brabander 16-13 Kennedy 3-A Buena Park Claudine Casey 17-12 Sunny Hills 1984 4-A Marina Dave Penn 16-13 Estancia 3-A Colton Sandra Guidi 19-10 Kennedy 1985 4-A Estancia Lillian Brabander 11-8 Buena Park 3-A Palm Springs Daryl Barton 11-8 Rosemead 1986 4-A Garden Grove Vicki Toutz 13-6 Nogales 3-A Colton Sandra Guidi 16-3 Palm Springs 1987 4-A Colton Sandra Guidi 14-5 Buena Park 3-A Mark Keppel Harold George 13-6 Covina 1988 4-A Glendale Pat Rogerson 12-7 Buena Park 3-A Rosemead Kathy Maier 11-8 Covina 1989 4-A Buena Park Michelle Tafoya 13-6 Nogales 3-A Jordan Harriett Sprague 10-9 Alta Loma 1990 4-A Buena Park Michelle Tafoya 10-9 Garden Grove 3-A Mark Keppel Harold George 15-4 Rosemead 1991 4-A Estancia Lillian Brabander 11-8 Buena Park 3-A Mark Keppel Harold George 13-9 Etiwanda 1992 4-A Estancia Lillian Brabander 12-7 Nogales 3-A Mark Keppel Harold George -

Ashley Thatcher, Junior Kelsey Hoffman and the 2007 Schedule

Angela Tincher Feb. 10-11 Georgia State Tournament (at Atlanta, Ga.) 10 vs. Tennessee Tech 10 a.m. vs. Alabama-Birmingham 12:15 p.m. 11 at Georgia State 12:15 p.m. Championship Play TBA 16-18 Tiger Invitational (at Auburn, Ala.) 16 vs. Tennessee Tech ^ 11 a.m. vs. Tulsa ^ 9 p.m. 17 at Auburn ^ 1:30 p.m. vs. Alabama-Birmingham ^ 9 p.m. 18 vs. Notre Dame ^ 1:30 p.m. 23-25 NFCA Leadoff Classic (at Columbus, Ga.) 23 vs. Coastal Carolina 2:30 p.m. vs. Lehigh 7:30 p.m. 24 vs. Georgia 3:30 p.m. Ashley vs. Illinois State 6 p.m. Thatcher 25 Championship Play TBA 28 at Radford (DH) 2 p.m. Mar. 2-4 Knight Games (at Altamonte Springs, Fla.) 2 vs. Jacksonville State 5 p.m. vs. UCF 7 p.m. 3 vs. Holy Cross 3 p.m. vs. Eastern Michigan 5 p.m. 4 TBA TBA 8-11 USF-adidas Spring Break Invitational (at Clearwater, Fla.) 8 vs. Central Michigan 4 p.m. vs. Fordham 6 p.m. 9 vs. Robert Morris 11 a.m. Karie vs. Hofstra 1 p.m. Morrison 10 vs. Ohio State 11 a.m. 11 Championship Play TBA 14 at South Carolina (DH) 4 p.m. 17 GEORGIA TECH (DH) * Noon Callie 18 GEORGIA TECH * 1 p.m. Rhodes 24 at Florida State (DH) * Noon 25 at Florida State * Noon 31 NORTH CAROLINA State (DH) * Noon April 1 NORTH CAROLINA State * 1 p.m. 4 at Longwood (DH) 4 p.m. -

SOONERS JAYHAWKS Vs

2013 OKLAHOMA SOFTBALL | SEVEN WCWS APPEARANCES | NINE BIG 12 TITLES | 2000 NATIONAL CHAMPIONS | 41 ALL-AMERICANS Karl Anderson, Assistant Communications Director McClendon Center for Intercollegiate Athletics 180 West Brooks, Suite 2525 | Norman, OK 73019 Phone: (405) 325-8571 | E-Mail: [email protected] www.SoonerSports.com | Twitter: @SoonerSoftball 88 ALL-REGION SELECTIONS | 8 BIG 12 PLAYERS OF THE YEAR | 4 BIG 12 DEFENSIVE PLAYERS OF THE YEAR | 68 ALL-BIG 12 FIRST TEAM HONOREES | 101 WEEKLY BIG 12 HONORS No. 1/1 Oklahoma Softball OKLAHOMA AT KANSAS 2013 Schedule (43-3, 11-1) Saturday: ............................2 p.m./4 p.m. FEBRUARY Sunday: .......................................12 p.m. Kajikawa Classic Venue: ..................................Arrocha Ballpark 08 vs. #21/20 Stanford Phoenix, Ariz. W, 6-0 vs. RV/RV Oregon State Phoenix, Ariz. W, 14-2 (5) Live Stats: ...................SoonerSports.com 09 vs. #5/6 Oregon Phoenix, Ariz. W, 12-0 (5) vs. New Mexico Phoenix, Ariz. W, 11-1 (5) 10 vs. RV/RV Northwestern Phoenix, Ariz. W, 7-4 OU vs. Kansas: .................OU leads 52-41 Campbell/Cartier Classic 15 vs. UC Riverside San Diego, Calif. W, 7-0 In Norman: ......................OU leads 28-13 at RV/NR San Diego St. San Diego, Calif. W, 4-0 16 vs. #24/22 Kentucky San Diego, Calif. W, 11-0 (5) In Lawrence: ....................OU leads 14-10 vs. #18/16 Washington San Diego, Calif. W, 2-0 17 vs. Notre Dame San Diego, Calif. W, 7-5 (9) At Neutral Site: ................KU leads 18-10 Mary Nutter Collegiate Classic Last Meeting: .............OU 6, KU 2; 4/1/12 21 vs. -

Directory of Information

2014 DIRECTORY OF INFORMATION 2014 NFCA Directory Four-Year Institutions ____________________________________ 4-68 Two-Year Institutions ____________________________________ 69-81 High Schools _________________________________________ 83-107 Travel Ball __________________________________________ 109-132 Affliates-Individuals ___________________________________ 134-141 Affliates-Businesses, Clubs & Sponsors ___________________ 143-146 Affiliates-Umpires ____________________________________ 148-149 Members-International _____________________________________ 150 NFCA Bylaws ________________________________________ 151-172 NFCA Board/Staff ________________________________________ 174 NFCA History _______________________________________ 175-176 NFCA Hall of Fame/2013 Coaching Staffs of the Year ________ 177-179 NFCA Code of Ethics ______________________________________ 180 The National Fastpitch Coaches Association is pleased to bring you this 2014 Directory of Information. The information contained within is based on our membership files as of January 17, 2014. Please contact us throughout the year concerning address, telephone or e-mail changes. Volume 19, No. 1 Made available one time per year by the National Fastpitch Coaches Association, 2641 Grinstead Drive, Louisville, Kentucky 40206. Phone: 502/409-4600; Fax: 502/409-4622. Members of the NFCA receive the directory for free; non-members can purchase for $10. 4 Four-Year Institutions A Adrian College Ralph Messura, Asst. -A- Kristina Schweikert, Head 1 Saxon Dr. 110 S. Madison McLane Center Abilene Christian University Adrian, MI 49221 Alfred, NY 14802 Bobby Reeves, Head Work 517/264-3998 [email protected] Box 27916 [email protected] Member Since 2013 Abilene, TX 79699-7916 NCAA III, NFCA C Work 806/786-3379 Member Since 2007 Allegheny College [email protected] Beth Curtiss, Head NCAA I, NFCA MW Lauren Nacke, Asst. 520 N. Main St. Member Since 1991 1225 Michigan Ave. -

Division I Records

Division I Records Individual Records .................................................................. 2 Individual Leaders .................................................................. 4 Annual Individual Champions .......................................... 18 Team Records ........................................................................... 24 Team Leaders ............................................................................ 25 Annual Team Champions .................................................... 32 2011 Most-Improved Teams .............................................. 35 All-Time Most-Improved Teams ........................................ 35 USA Today/National Fastpitch Coaches Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 36 Statistical Trends ...................................................................... 37 2 NCAA DIVISION I SOFTBALL RECORDS THROUGH 2011 Individual Records Official NCAA softball records began with the Career BASES ON BALLS 1982 season and are based on information sub- 0.37—Crystal Boyd, Hofstra, 1991-94 (68 in 183 games) Game mitted to the NCAA statistics service by insti- TRIPLES 6—Wendy Stewart, Utah vs. Creighton, May 12, 1991 tutions participating in the statistics rankings. Game (25 inn.); Oli Keohohou, BYU vs. Utah, May 12, 2001 Official career records of players include only 3—Nine times, most recent: Hayle Guess, Mississippi St. (10 inn.) vs. Ole Miss, April 7, 2007 Consecutive those years in which they competed in Division