'I Used to Love Him': Exploring The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

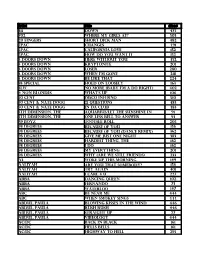

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Katy Perry's Pinup Perfect

Culture MONDAY, AUGUST 9, 2010 an you read sheet music?” asks Katy a rocket and you’re hanging on for dear life and Perry as we climb the stairs of a photo you’re like, ‘Gooooooo!’ The second record I’m studio on Broadway. more buckled in because, God, how many times do “A little,” I say. you see people slump on their sophomore record? She stops and holds out the edges Katy Perry’s Nine out of 10. But I’m still working, like, 13-hour “Cof her dress, patterned with a series of ascending days, five, six days a week and singing on top of it. quavers and semiquavers. “Then what song am I?” she And knowing that there’s someone right behind me, asks, twirling. ready to go, ready to push me down the stairs, just “Three Blind Mice?” like in Showgirls.” “The Girl From Ipanema,” she says, before The middle child of three, her parents were breaking into song. “I feel like I’m squeezed into a pinup both born-again Pentecostal ministers in southern giant condom in this dress,” she adds. California — Christian camp, Christian friends, no Retro pop reference, modern twist, smutty MTV, no radio — but press stories of a parental punchline: I’m with the right Katy Perry, then. It’s a rift over Perry’s lyrics ignore the “born again” bit. sweltering day in Manhattan — temperatures are in Before they came to their faith, her parents were the 30s — but Perry, who arrived from Los Angeles perfect 60s scenesters, her mother briefly dating Jimi a few days ago, isn’t complaining. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Andrzej Antoszek Catholic University of Lublin English Department American Studies Al. Raclawickie 14 20-950 Lublin, Poland Tel./Fax

Andrzej Antoszek Catholic University of Lublin English Department American Studies Al. Raclawickie 14 20-950 Lublin, Poland tel./fax. (081) 5332572 e-mail: [email protected] HOPPING ON THE HYPE: DOUBLE ONTOLOGY OF (CONTEMPORARY) AMERICAN RAP MUSIC In a revealing interview with Elisabeth A. Frost, Harryette Mullen, one of the most enthralling African-American poets, tries to answer the question of contemporary black identity and authenticity, the search for which seems to the interviewer to be a rather “nostalgic gesture.” Mullen’s answer, the response of a literary figure who is-- at the same time-- a person living and teaching in Los Angeles and thus familiar with all the latest fads that black communities adopt, is full of concern for the inevitability of the changes that the global culture imposes on once unique identifying characteristics. Mullen observes that “part of what is tricky and difficult is wondering whether we even know what we believe about ourselves. So often we are performing, and we are paid for performing – we are surviving, assimilating, blending in. When are we ourselves? Beyond being either a credit or discredit to our race, who are we?” (Frost: 416). Mullen’s words, a shrouded lament for the disappearance of the singular and distinctive in favor of the global and homogenized, could easily be applied to the phenomenon which has soared from its Compton ragged origins to the riches of the luxurious corporate environment, turning poor boys with ghetto blasters into moguls of show business. Contemporary rap music has acquired in the course of a decade or so a double, triple, or even multiple ontology, capitalizing on its initial niche and vaguely ominous character and exchanging the message for endless permutations of the form. -

Steve's Karaoke Songbook

Steve's Karaoke Songbook Artist Song Title Artist Song Title +44 WHEN YOUR HEART STOPS INVISIBLE MAN BEATING WAY YOU WANT ME TO, THE 10 YEARS WASTELAND A*TEENS BOUNCING OFF THE CEILING 10,000 MANIACS CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE MORE THAN THIS AALIYAH ONE I GAVE MY HEART TO, THE THESE ARE THE DAYS TRY AGAIN TROUBLE ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN 10CC THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE FERNANDO 112 PEACHES & CREAM GIMME GIMME GIMME 2 LIVE CREW DO WAH DIDDY DIDDY I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ME SO HORNY I HAVE A DREAM WE WANT SOME PUSSY KNOWING ME, KNOWING YOU 2 PAC UNTIL THE END OF TIME LAY ALL YOUR LOVE ON ME 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME MAMMA MIA 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS DO FOR LOVE SOS 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE SUPER TROUPER 3 DOORS DOWN BEHIND THOSE EYES TAKE A CHANCE ON ME HERE WITHOUT YOU THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC KRYPTONITE WATERLOO LIVE FOR TODAY ABBOTT, GREGORY SHAKE YOU DOWN LOSER ABC POISON ARROW ROAD I'M ON, THE ABDUL, PAULA BLOWING KISSES IN THE WIND WHEN I'M GONE COLD HEARTED 311 ALL MIXED UP FOREVER YOUR GIRL DON'T TREAD ON ME KNOCKED OUT DOWN NEXT TO YOU LOVE SONG OPPOSITES ATTRACT 38 SPECIAL CAUGHT UP IN YOU RUSH RUSH HOLD ON LOOSELY STATE OF ATTRACTION ROCKIN' INTO THE NIGHT STRAIGHT UP SECOND CHANCE WAY THAT YOU LOVE ME, THE TEACHER, TEACHER (IT'S JUST) WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 3T TEASE ME BIG BALLS 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 50 CENT AMUSEMENT PARK FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK (WE SALUTE YOU) CANDY SHOP GIRLS GOT RHYTHM DISCO INFERNO HAVE A DRINK ON ME I GET MONEY HELLS BELLS IN DA -

The Jacksonville Symphony Returns to Daily's Place Alongside Grammy-Winner Wyclef Jean

THE JACKSONVILLE SYMPHONY RETURNS TO DAILY’S PLACE ALONGSIDE GRAMMY-WINNER WYCLEF JEAN “Do yourself a favor: get lose, have a ball, have fun.” – Wyclef Jean Jacksonville, FL (February 28, 2018) --- The Jacksonville Symphony returns to Daily’s Place for A Night of Symphonic Hip Hop. Produced by Live Nation Urban and TCG Entertainment, the concert will feature three-time Grammy winner and hip hop guitarist, Wyclef Jean. The concert will take place on Saturday, March 10 at 8 p.m. at Daily’s Place. WHO: Although known for his successful hip hop career, Wyclef Jean has a diverse musical background that includes classical music. By the time the star was 15, Jean could already play more than 10 musical instruments and his school teacher suggested he take courses in jazz and classical music. With an initial adverse reaction, the hip hop sensation admits the experience had impact on his musical growth. “It changed my head,” Jean said in an interview with Columbus Alive. “I started listening to Bach, Thelonious and Gershwin.” WHAT: Years later, Wyclef Jean will fuse his love of hip hop and classical music with a performance of some of his greatest hits live with the Jacksonville Symphony. The music that he has written, performed and produced has been a consistently powerful, pop cultural force for over two decades. In 1996, the Fugees, a group Wyclef founded, released their monumental album The Score. The album hit No. 1 on the Billboard chart, spawned a trio of smash singles and is now certified six times platinum. Wyclef went on to write and produce Shakira’s chart-topping single "Hips Don’t Lie," which climbed to No. -

Artist Song Album Blue Collar Down to the Line Four Wheel Drive

Artist Song Album (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Blue Collar Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Down To The Line Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Four Wheel Drive Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Free Wheelin' Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Gimme Your Money Please Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Hey You Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Let It Ride Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Lookin' Out For #1 Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Roll On Down The Highway Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Take It Like A Man Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Hits of 1974 (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothin' Yet Hits of 1974 (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. Blue Sky Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Rockaria Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Showdown Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Strange Magic Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Sweet Talkin' Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Telephone Line Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Turn To Stone Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. -

Bad Bitches, Jezebels, Hoes, Beasts, and Monsters

BAD BITCHES, JEZEBELS, HOES, BEASTS, AND MONSTERS: THE CREATIVE AND MUSICAL AGENCY OF NICKI MINAJ by ANNA YEAGLE Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Thesis Adviser: Dr. Francesca Brittan, Ph.D. Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY August, 2013 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis of ____ ______ _____ ____Anna Yeagle_____________ ______ candidate for the __ __Master of Arts__ ___ degree.* __________Francesca Brittan__________ Committee Chair __________Susan McClary__________ Committee Member __________Daniel Goldmark__________ Committee Member (date)_____June 17, 2013_____ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures i Acknowledgements ii Abstract iii INTRODUCTION: “Bitch Bad, Woman Good, Lady Better”: The Semiotics of Power & Gender in Rap 1 CHAPTER 1: “You a Stupid Hoe”: The Problematic History of the Bad Bitch 20 Exploiting Jezebel 23 Nicki Minaj and Signifying 32 The Power of Images 42 CHAPTER 2: “I Just Want to Be Me and Do Me”: Deconstruction and Performance of Selfhood 45 Ambiguous Selfhood 47 Racial Ambiguity 50 Sexual Ambiguity 53 Gender Ambiguity 59 Performing Performativity 61 CHAPTER 3: “You Have to be a Beast”: Using Musical Agency to Navigate Industry Inequities 67 Industry Barriers 68 Breaking Barriers 73 Rap Credibility and Commercial Viability 75 Minaj the Monster 77 CONCLUSION: “You Can be the King, but Watch the Queen -

Music List (PDF)

Artist Title disc# 311 Down 475 702 Where My Girls At? 503 20 fingers short dick man 482 2pac changes 491 2Pac California Love 152 2Pac How Do You Want It 152 3 Doors Down Here Without You 452 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 201 3 doors down loser 280 3 Doors Down when I'm gone 218 3 Doors Down Be Like That 224 38 Special Hold On Loosely 163 3lw No more (baby I'm a do right) 402 4 Non Blondes What's Up 106 50 Cent Disco Inferno 510 50 cent & nate dogg 21 questions 483 50 cent & nate dogg in da club 483 5th Dimension, The aquarius/let the sunshine in 91 5th Dimension, The One Less Bell To Answer 93 69 Boyz Tootsee Roll 205 98 Degrees Because Of You 156 98 Degrees Because Of You (Dance Remix) 362 98 degrees Give me just one Night 383 98 Degrees Hardest Thing, the 162 98 Degrees I Do 162 98 Degrees My Everything 201 98 Degrees Why (Are We Still Friends) 233 A3 Woke Up This Morning 149 Aaliyah Are You That Somebody? 156 aaliyah Try again 401 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 227 Abba Dancing Queen 102 ABBA FERNANDO 73 ABBA Waterloo 147 ABC Be Near Me 444 ABC When Smokey Sings 444 ABDUL, PAULA Blowing Kisses In The Wind 446 ABDUL, PAULA Rush Rush 446 ABDUL, PAULA STRAIGHT UP 27 ABDUL, PAULA Vibeology 444 AC/DC Back In Black 161 AC/DC Hells Bells 161 AC/DC Highway To Hell 295 AC/DC Stiff Upper Lip 295 AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie 295 AC/dc You shook me all night long 108 Ace Of Base Beautiful Life 8 Ace of Base Don't Turn Around 154 Ace Of Base Sign, The 206 AD LIBS BOY FROM NEW YORK CITY, THE 49 adam ant goody two shoes 108 ADAMS, BRYAN (EVERYTHING I DO) I DO IT FOR YOU -

Party Warehouse Jukebox Song List

Party Warehouse Jukebox Song List Please note that this is a sample song list from one Party Warehouse Digital Jukebox. Each jukebox will vary slightly so we cannot gaurantee a particular song will be on your jukebox Song# ARTIST SONG TITLE 1 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 2 28 DAYS RIP IT UP 3 28 DAYS AND APOLLO FOUR FORTY SAY WHAT 4 3 DOORS DOWN BE LIKE THAT 5 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU 6 3 DOORS DOWN ITS NOT MY TIME 7 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 8 3 DOORS DOWN LET ME GO 9 3 DOORS DOWN LOSER 10 3 JAYS FEELING IT TOO 11 3 JAYS IN MY EYES 12 3 THE HARDWAY ITS ON 13 30 SECONDS TO MARS CLOSER TO THE EDGE 14 3LW NO MORE 15 3O!H3 FT KATY PERRY STARSTRUKK 16 3OH!3 DONT TRUST ME 17 3OH!3 DOUBLE VISION 18 3OH!3 STARSTRUKK ALBUM VERSION 19 3OH!3 AND KESHA MY FIRST KISS 20 4 NON BLONDES CALLING ALL THE PEOPLE 21 4 NON BLONDES DEAR MR PRESIDENT 22 4 NON BLONDES DRIFTING 23 4 NON BLONDES MORPHINE AND CHOCOLATE 24 4 NON BLONDES NO PLACE LIKE HOME 25 4 NON BLONDES OLD MR HEFFER 26 4 NON BLONDES PLEASANTLY BLUE 27 4 NON BLONDES SPACEMAN 28 4 NON BLONDES SUPERFLY 29 4 NON BLONDES TRAIN 30 4 NON BLONDES WHATS UP 31 48 MAY BIGSHOCK 32 48 MAY HOME BY 2 33 48 MAY INTO THE SUN 34 48 MAY LEATHER AND TATTOOS 35 48 MAY NERVOUS WRECK 36 50 CENT 21 QUESTIONS 37 50 CENT CANDY SHOP 38 50 CENT IN DA CLUB 39 50 CENT JUST A LIL BIT 40 50 CENT PIMP 41 50 CENT STRAIGHT TO THE BANK 42 50 CENT WINDOW SHOPPER 43 50 CENT AND JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE AYO TECHNOLOGY 44 6400 CREW HUSTLERS REVENGE Party Warehouse Jukebox Songlist Song# ARTIST SONG TITLE 45 98 DEGREES GIVE ME JUST ONE NIGHT -

Lauryn Hill “Everything Is Everything”

Lauryn Hill “Everything Is Everything” Teacher Guide ©2007 Educational Lyrics LLC Copyright © 2007 by Educational Lyrics, LLC H.E.L.P. – Lauryn Hill, “Everything Is Everything’ Teacher Guide Created by: Rick Henning, Gabriel Benn Project Manager: Dayna Edwards Contributors: Rahaman Kilpatrick, Felicity Loome, Claude Nadir, Selma Woldemichael, Aimee Worsham Illustrator: Phillip Spence Cover Art: Khalil Gill The purpose of H.E.L.P. exercises is to create teachable moments between student and instructor. Any views expressed herein by the Artist should not be construed as an endorsement by Educational Lyrics or its affi liates of the views contained therein. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 1-934212-11-3 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................. 5 Artist Biography ........................................................................................................... 6 Song Lyrics .................................................................................................................... 7 Vocabulary .................................................................................................................. 8 Writing Rubric ...............................................................................................................9 Multiple Intelligences Activities -

Iâ•Žm Gonna Find You and Make You Want Me

Intertext Volume 17 Article 13 1-1-2009 I’m Gonna Find You and Make You Want Me Joanna Meyers Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/intertext Part of the Fiction Commons, and the Nonfiction Commons Recommended Citation Meyers, Joanna (2009) "I’m Gonna Find You and Make You Want Me," Intertext: Vol. 17 , Article 13. Available at: https://surface.syr.edu/intertext/vol17/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Intertext by an authorized editor of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. e m h en do t c is n o W o nn d lk i ol ta y Meyers: I’m Gonna Find You and Make You Want Me eh k la b lic p to s to t an’t t igh nt C an s pe w a re ys t lwa a nd a h a es it w r s c , e o s e p n y s k o H s fl i e e l l h c l a n n n e d e o i r ’ c n n i u w o o o c y d t o w e n g o N o s i t l d o e e r c e t n n n e o m u c i q h t e ’ n n s a e n c h u o rab h o W o g old of y C wha t ed th man wan t Gain e w t to act p ? h s li m t tra k e d ig e x l h h e n o t, e’s c I’m on ho e w w b n no y r y o le u s ser ur y t s a w t e hole s k l to l e a p r t a o il r h u m o s i y a s e w s m ’ o I c t n w ld ho o e No ow g w, n m nd e be r a v tter th an silve o d m ay r of ou judge ment Y “I’m Gonna Find You and Make You Want Me” Joanna Myers Course: WRT 303, Research & Writing Instructor: Henry Jankiewicz Author’s Note: The assignment was to describe your relationship with one of your favorite CDs in a literary jour- nalistic style, using a collage of time periods and voices.