An Exploration of the Judd Street Bridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inland Zone Sub-Area Contingency Plan (SACP) for Minneapolis/St

EPA REGION 5 INLAND ZONE SUB-AREA CONTINGENCY PLAN Inland Zone Sub-Area Contingency Plan (SACP) for Minneapolis/St. Paul December 2020 Sub-Area Contingency Plan i Minneapolis/St. Paul Letter of Review Minneapolis/St. Paul Inland Zone Sub-Area Contingency Plan (SACP) This SACP has been prepared by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under the direction of the Federal On-Scene Coordinator (OSC) with collaboration from stakeholders of the Minneapolis/St. Paul Inland Zone Sub-Area. This SACP has been prepared for the use of all agencies engaged in responding to environmental emergencies and contains useful tools for responders, providing practical and accessible information about who and what they need to know for an effective response. This SACP is not intended to serve as a prescriptive plan for response but as a mechanism to ensure responders have access to essential sub-area specific information and to promote interagency coordination for an effective response. This SACP includes links to documents and information on non-EPA sites. Links to non-EPA sites and documents do not imply any official EPA endorsement of, or responsibility for, the opinions, ideas, data or products presented at those locations, or guarantee the validity of the information provided. David Morrison Federal On-Scene Coordinator United States Environmental Protection Agency Superfund & Emergency Management Division Region 5 Sub-Area Contingency Plan ii Minneapolis/St. Paul Record of Change Change SACP Description of Change Initials Date Number Section 1 all EPA R5 2020 New Sub Area Format – IAP w/main body plan DHM 12/22/2020 Sub-Area Contingency Plan iii Minneapolis/St. -

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Chapter 85

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 85.011 CHAPTER 85 DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION STATE PARKS, RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES 85.06 SCHOOLHOUSES IN CERTAIN STATE PARKS. 85.011 CONFIRMATION OF CREATION AND 85.20 VIOLATIONS OF RULES; LITTERING; PENALTIES. ESTABLISHMENT OF STATE PARKS, STATE 85.205 RECEPTACLES FOR RECYCLING. RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES. 85.21 STATE OPERATION OF PARK, MONUMENT, 85.0115 NOTICE OF ADDITIONS AND DELETIONS. RECREATION AREA AND WAYSIDE FACILITIES; 85.012 STATE PARKS. LICENSE NOT REQUIRED. 85.013 STATE RECREATION AREAS AND WAYSIDES. 85.22 STATE PARKS WORKING CAPITAL ACCOUNT. 85.014 PRIOR LAWS NOT ALTERED; REVISOR'S DUTIES. 85.23 COOPERATIVE LEASES OF AGRICULTURAL 85.0145 ACQUIRING LAND FOR FACILITIES. LANDS. 85.0146 CUYUNA COUNTRY STATE RECREATION AREA; 85.32 STATE WATER TRAILS. CITIZENS ADVISORY COUNCIL. 85.33 ST. CROIX WILD RIVER AREA; LIMITATIONS ON STATE TRAILS POWER BOATING. 85.015 STATE TRAILS. 85.34 FORT SNELLING LEASE. 85.0155 LAKE SUPERIOR WATER TRAIL. TRAIL PASSES 85.0156 MISSISSIPPI WHITEWATER TRAIL. 85.40 DEFINITIONS. 85.016 BICYCLE TRAIL PROGRAM. 85.41 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI PASSES. 85.017 TRAIL REGISTRY. 85.42 USER FEE; VALIDITY. 85.018 TRAIL USE; VEHICLES REGULATED, RESTRICTED. 85.43 DISPOSITION OF RECEIPTS; PURPOSE. ADMINISTRATION 85.44 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI TRAIL GRANT-IN-AID 85.019 LOCAL RECREATION GRANTS. PROGRAM. 85.021 ACQUIRING LAND; MINNESOTA VALLEY TRAIL. 85.45 PENALTIES. 85.04 ENFORCEMENT DIVISION EMPLOYEES. 85.46 HORSE -

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Section 138.662

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 138.662 138.662 HISTORIC SITES. Subdivision 1. Named. Historic sites established and confirmed as historic sites together with the counties in which they are situated are listed in this section and shall be named as indicated in this section. Subd. 2. Alexander Ramsey House. Alexander Ramsey House; Ramsey County. History: 1965 c 779 s 3; 1967 c 54 s 4; 1971 c 362 s 1; 1973 c 316 s 4; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 3. Birch Coulee Battlefield. Birch Coulee Battlefield; Renville County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1973 c 316 s 9; 1976 c 106 s 2,4; 1984 c 654 art 2 s 112; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 4. [Repealed, 2014 c 174 s 8] Subd. 5. [Repealed, 1996 c 452 s 40] Subd. 6. Camp Coldwater. Camp Coldwater; Hennepin County. History: 1965 c 779 s 7; 1973 c 225 s 1,2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 7. Charles A. Lindbergh House. Charles A. Lindbergh House; Morrison County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1969 c 956 s 1; 1971 c 688 s 2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 8. Folsom House. Folsom House; Chisago County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 9. Forest History Center. Forest History Center; Itasca County. History: 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 10. Fort Renville. Fort Renville; Chippewa County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1973 c 225 s 3; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. -

Trail Challenge Resources

Trail Challenge Resources Hiking Trails Ice Age National Scenic Trail ● Description: One of only 11 National Scenic Trails in the country, the Ice Age Trail is a 1,000-mile footpath contained entirely within the state of Wisconsin. Ancient glaciers carved the path through rocky terrain, open prairies, and peaceful forests. Now, day hikers, backpackers, and outdoor lovers of all ages rely on the Ice Age Trail for a place to unplug, relax, and enjoy nature. ● Ice Age Trail Map Interstate State Park, MN ● Description: Interstate State Park includes 293 acres of diverse plant and wildlife habitat. Established in 1895, it protects a unique landscape and globally-significant geology along the St. Croix River. A billion years ago, dark basalt rock formed here when lava escaped from a crack in the earth’s crust. Just ten thousand years ago, water from melting glaciers carved the river valley. Within that water were fast moving whirlpools of swirling sand and water that wore deep holes into the rock. Today, we call these holes glacial potholes and you can see more than 400 examples of them at the park. ● Interstate State Park Map Interstate State Park, WI ● Description: There are more than nine miles of hiking trails in the park that offer the walker many opportunities for viewing the spectacular scenery and natural attributes of the park. Guided hikes are offered during the summer months. Pets must be on a leash 8 feet or shorter at all times. Hiking trails vary in difficulty. Not all trails are surfaced; use caution on steep bluffs and near cliffs. -

The Campground Host Volunteer Program

CAMPGROUND HOST PROGRAM THE CAMPGROUND HOST VOLUNTEER PROGRAM MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 1 CAMPGROUND HOST PROGRAM DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION Introduction This packet is designed to give you the information necessary to apply for a campground host position. Applications will be accepted all year but must be received at least 30 days in advance of the time you wish to serve as a host. Please send completed applications to the park manager for the park or forest campground in which you are interested. Addresses are listed at the back of this brochure. General questions and inquiries may be directed to: Campground Host Coordinator DNR-Parks and Recreation 500 Lafayette Road St. Paul, MN 55155-4039 651-259-5607 [email protected] Principal Duties and Responsibilities During the period from May to October, the volunteer serves as a "live in" host at a state park or state forest campground for at least a four-week period. The primary responsibility is to assist campers by answering questions and explaining campground rules in a cheerful and helpful manner. Campground Host volunteers should be familiar with state park and forest campground rules and should become familiar with local points of interest and the location where local services can be obtained. Volunteers perform light maintenance work around the campground such as litter pickup, sweeping, stocking supplies in toilet buildings and making emergency minor repairs when possible. Campground Host volunteers may be requested to assist in the naturalist program by posting and distributing schedules, publicizing programs or helping with programs. Volunteers will set an example by being model campers, practicing good housekeeping at all times in and around the host site, and by observing all rules. -

Minnesota State Parks.Pdf

Table of Contents 1. Afton State Park 4 2. Banning State Park 6 3. Bear Head Lake State Park 8 4. Beaver Creek Valley State Park 10 5. Big Bog State Park 12 6. Big Stone Lake State Park 14 7. Blue Mounds State Park 16 8. Buffalo River State Park 18 9. Camden State Park 20 10. Carley State Park 22 11. Cascade River State Park 24 12. Charles A. Lindbergh State Park 26 13. Crow Wing State Park 28 14. Cuyuna Country State Park 30 15. Father Hennepin State Park 32 16. Flandrau State Park 34 17. Forestville/Mystery Cave State Park 36 18. Fort Ridgely State Park 38 19. Fort Snelling State Park 40 20. Franz Jevne State Park 42 21. Frontenac State Park 44 22. George H. Crosby Manitou State Park 46 23. Glacial Lakes State Park 48 24. Glendalough State Park 50 25. Gooseberry Falls State Park 52 26. Grand Portage State Park 54 27. Great River Bluffs State Park 56 28. Hayes Lake State Park 58 29. Hill Annex Mine State Park 60 30. Interstate State Park 62 31. Itasca State Park 64 32. Jay Cooke State Park 66 33. John A. Latsch State Park 68 34. Judge C.R. Magney State Park 70 1 35. Kilen Woods State Park 72 36. Lac qui Parle State Park 74 37. Lake Bemidji State Park 76 38. Lake Bronson State Park 78 39. Lake Carlos State Park 80 40. Lake Louise State Park 82 41. Lake Maria State Park 84 42. Lake Shetek State Park 86 43. -

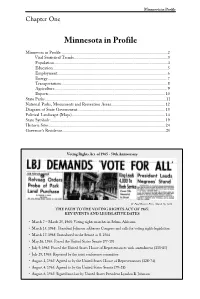

Minnesota in Profile

Minnesota in Profile Chapter One Minnesota in Profile Minnesota in Profile ....................................................................................................2 Vital Statistical Trends ........................................................................................3 Population ...........................................................................................................4 Education ............................................................................................................5 Employment ........................................................................................................6 Energy .................................................................................................................7 Transportation ....................................................................................................8 Agriculture ..........................................................................................................9 Exports ..............................................................................................................10 State Parks...................................................................................................................11 National Parks, Monuments and Recreation Areas ...................................................12 Diagram of State Government ...................................................................................13 Political Landscape (Maps) ........................................................................................14 -

Campground Host Program

Campground Host Program MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF PARKS AND TRAILS Updated November 2010 Campground Host Program Introduction This packet is designed to give you the information necessary to apply for a campground host position. Applications will be accepted all year but must be received at least 30 days in advance of the time you wish to serve as a host. Please send completed applications to the park manager for the park or forest campground in which you are interested. You may email your completed application to [email protected] who will forward it to your first choice park. General questions and inquiries may be directed to: Campground Host Coordinator DNR-Parks and Trails 500 Lafayette Road St. Paul, MN 55155-4039 Email: [email protected] 651-259-5607 Principal Duties and Responsibilities During the period from May to October, the volunteer serves as a "live in" host at a state park or state forest campground for at least a four-week period. The primary responsibility is to assist campers by answering questions and explaining campground rules in a cheerful and helpful manner. Campground Host volunteers should be familiar with state park and forest campground rules and should become familiar with local points of interest and the location where local services can be obtained. Volunteers perform light maintenance work around the campground such as litter pickup, sweeping, stocking supplies in toilet buildings and making emergency minor repairs when possible. Campground Host volunteers may be requested to assist in the naturalist program by posting and distributing schedules, publicizing programs or helping with programs. -

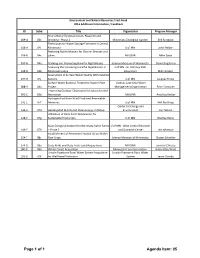

Of 1 Agenda Item: 05 ENRTF ID: 009-A / Subd

Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund 2016 Additional Information / Feedback ID Subd. Title Organization Program Manager Prairie Butterfly Conservation, Research and 009‐A 03c Breeding ‐ Phase 2 Minnesota Zoological Garden Erik Runquist Techniques for Water Storage Estimates in Central 018‐A 04i Minnesota U of MN John Neiber Restoring Native Mussels for Cleaner Streams and 036‐B 04c Lakes MN DNR Mike Davis 037‐B 04a Tracking and Preventing Harmful Algal Blooms Science Museum of Minnesota Daniel Engstrom Assessing the Increasing Harmful Algal Blooms in U of MN ‐ St. Anthony Falls 038‐B 04b Minnesota Lakes Laboratory Miki Hondzo Assessment of Surface Water Quality With Satellite 047‐B 04j Sensors U of MN Jacques Finlay Surface Water Bacterial Treatment System Pilot Vadnais Lake Area Water 088‐B 04u Project Management Organization Brian Corcoran Improving Outdoor Classrooms for Education and 091‐C 05b Recreation MN DNR Amy Kay Kerber Hydrogen Fuel from Wind Produced Renewable 141‐E 07f Ammonia U of MN Will Northrop Center for Energy and 144‐E 07d Geotargeted Distributed Clean Energy Initiative Environment Carl Nelson Utilization of Dairy Farm Wastewater for 148‐E 07g Sustainable Production U of MN Bradley Heins Solar Energy Utilization for Minnesota Swine Farms U of MN ‐ West Central Research 149‐E 07h – Phase 2 and Outreach Center Lee Johnston Establishment of Permanent Habitat Strips Within 154‐F 08c Row Crops Science Museum of Minnesota Shawn Schottler 174‐G 09a State Parks and State Trails Land Acquisitions MN DNR Jennifer Christie 180‐G 09e Wilder Forest Acquisition Minnesota Food Association Hilary Otey Wold Lincoln Pipestone Rural Water System Acquisition Lincoln Pipestone Rural Water 181‐G 09f for Well Head Protection System Jason Overby Page 1 of 1 Agenda Item: 05 ENRTF ID: 009-A / Subd. -

Quest for Excellence: a History Of

QUEST FOR EXCELLENCE a history of the MINNESOTA COUNCIL OF PARKS 1954 to 1974 By U. W Hella Former Director of State Parks State of Minnesota Edited By Robert A. Watson Associate Member, MCP Published By The Minnesota Parks Foundation Copyright 1985 Cover Photo: Wolf Creek Falls, Banning State Park, Sandstone Courtesy Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Dedicated to the Memory of JUDGE CLARENCE R. MAGNEY (1883 - 1962) A distinguished jurist and devoted conser vationist whose quest for excellence in the matter of public parks led to the founding of the Minnesota Council of State Parks, - which helped insure high standards for park development in this state. TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward ............................................... 1 I. Judge Magney - "Giant of the North" ......................... 2 II. Minnesota's State Park System .............................. 4 Map of System Units ..................................... 6 Ill. The Council is Born ...................................... 7 IV. The Minnesota Parks Foundation ........................... 9 Foundation Gifts ....................................... 10 V. The Council's Role in Park System Growth ................... 13 Chronology of the Park System, 1889-1973 ................... 14 VI. The Campaign for a National Park ......................... 18 Map of Voyageurs National Park ........................... 21 VII. Recreational Trails and Boating Rivers ....................... 23 Map of Trails and Canoe Routes ........................... 25 Trail Legislation, 1971 ................................... -

2005 Project Abstract for the Period Ending June 30, 2008

2005 Project Abstract For the Period Ending June 30, 2008 TITLE: Metro Conservation Corridors – Phase II PROJECT MANAGER: Wayne Sames ORGANIZATION: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources ADDRESS: OMBS, Box 10, 500 Lafayette Road WEB SITE ADDRESS: [email protected] FUND: Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund LEGAL CITATION: ML 2005, 1st Spec. Sess., Chap. 1, Art. 2, Sec. 11, Subd. 5b APPROPRIATION AMOUNT: $3,530,000 Overall Project Outcome and Results The key objectives and results of this program are to accelerate agency programs and cooperative agreements with partners organizations for the purposes of planning, improving, and protecting important natural areas in the metropolitan region and portions of surrounding counties through grants, contracted services, conservation easements, and fee acquisition. The primary results of the program were: • Restoration of 2,026 acres of habitat • Protection of approximately 2.4 miles of shoreline • Fee and easement acquisition of 2,973 acres See individual partner work programs for detailed information on individual projects. Project Results, Use and Dissemination The Metro Corridors partnership distributed information about the program and projects through the widely broadcasted e-mails to people on the Regional Greenways Collaborative (RGC) database, through the RGC quarterly meetings, and jointly held county meetings. As projects were completed, the partners publicized accomplishments through press releases and organization newsletters and websites. LCMR Final Work Program Report OVERALL FINAL REPORT Date of Report: December, 2008 Date of Work program Approval: June 14, 2005 Project Completion Date: June 30, 2008 I. PROJECT TITLE: Metro Conservation Corridors – Phase II – Overall Summary Project Manager: Wayne Sames Affiliation: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Mailing Address: OMBS, Box 10, 500 Lafayette Road City / State / Zip: St. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or

G4127 NORTHWESTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G4127 FEATURES, ETC. .C8 Custer National Forest .L4 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail .L5 Little Missouri River .M3 Madison Aquifer .M5 Missouri River .M52 Missouri River [wild & scenic river] .O7 Oregon National Historic Trail. Oregon Trail .W5 Williston Basin [geological basin] .Y4 Yellowstone River 1305 G4132 WEST NORTH CENTRAL STATES. REGIONS, G4132 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .D4 Des Moines River .R4 Red River of the North 1306 G4142 MINNESOTA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G4142 .A2 Afton State Park .A4 Alexander, Lake .A42 Alexander Chain .A45 Alice Lake [Lake County] .B13 Baby Lake .B14 Bad Medicine Lake .B19 Ball Club Lake [Itasca County] .B2 Balsam Lake [Itasca County] .B22 Banning State Park .B25 Barrett Lake [Grant County] .B28 Bass Lake [Faribault County] .B29 Bass Lake [Itasca County : Deer River & Bass Brook townships] .B3 Basswood Lake [MN & Ont.] .B32 Basswood River [MN & Ont.] .B323 Battle Lake .B325 Bay Lake [Crow Wing County] .B33 Bear Head Lake State Park .B333 Bear Lake [Itasca County] .B339 Belle Taine, Lake .B34 Beltrami Island State Forest .B35 Bemidji, Lake .B37 Bertha Lake .B39 Big Birch Lake .B4 Big Kandiyohi Lake .B413 Big Lake [Beltrami County] .B415 Big Lake [Saint Louis County] .B417 Big Lake [Stearns County] .B42 Big Marine Lake .B43 Big Sandy Lake [Aitkin County] .B44 Big Spunk Lake .B45 Big Stone Lake [MN & SD] .B46 Big Stone Lake State Park .B49 Big Trout Lake .B53 Birch Coulee Battlefield State Historic Site .B533 Birch Coulee Creek .B54 Birch Lake [Cass County : Hiram & Birch Lake townships] .B55 Birch Lake [Lake County] .B56 Black Duck Lake .B57 Blackduck Lake [Beltrami County] .B58 Blue Mounds State Park .B584 Blueberry Lake [Becker County] .B585 Blueberry Lake [Wadena County] .B598 Boulder Lake Reservoir .B6 Boundary Waters Canoe Area .B62 Bowstring Lake [Itasca County] .B63 Boy Lake [Cass County] .B68 Bronson, Lake 1307 G4142 MINNESOTA.