On Ratites and Their Interactions with Plants*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

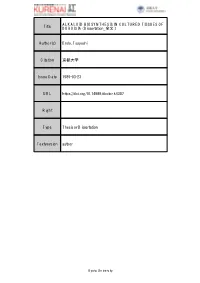

Title ALKALOID BIOSYNTHESIS in CULTURED TISSUES OF

ALKALOID BIOSYNTHESIS IN CULTURED TISSUES OF Title DUBOISIA( Dissertation_全文 ) Author(s) Endo, Tsuyoshi Citation 京都大学 Issue Date 1989-03-23 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/doctor.k4307 Right Type Thesis or Dissertation Textversion author Kyoto University ALKALOID BIOSYNTHESIS IN C;ULTURED TISSUES OF DUBOISIA . , . ; . , " 1. :'. '. o , " ::,,~./ ~ ~';-~::::> ,/ . , , .~ - '.'~ . / -.-.........."~l . ~·_l:""· .... : .. { ." , :: I i i , (, ' ALKALOID BIOSYNTHESIS IN CULTURED TISSUES OF DUBOISIA TSUYOSHIENDO 1989 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ----------1 CHAPTER I ALKALOID PRODUCTION IN CULTURED DUBOISIA TISSUES. INTRODUCTION ----------6 SECTION 1 Alkaloid Production and Plant Regeneration from ~ leichhardtii Calluses. ----------8 SECTION 2 Alkaloid Production in Cultured Roots of Three Species of Duboisia. ---------16 SECTION 3 Non-enzymatic Synthesis of Hygrine from Acetoacetic Acid and from Acetonedicar- boxylic Acid. ---------25 CHAPTER II SOMATIC HYBRIDIZATION OF DUBOISIA AND NICOTIANA. INTRODUCTION ---------35 SECTION 1 Establishment of an Intergeneric Hybrid Cell Line of ~ hopwoodii and ~ tabacum. ---------38 SECTION 2 Genetic Diversity Originating from a Single Somatic Hybrid Cell. ---------47 SECTION 3 Alkaloid Biosynthesis in Somatic Hybrids, D. leichhardtii + ~ tabacum ---------59 CONCLUSIONS ---------76 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ---------79 REFERENCES ---------80 PUBLICATIONS ---------90 ABBREVIATIONS BA 6-benzyladenine OAPI 4',6-diamino-2-phenylindoledihydrochloride EDTA ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid GC-MS gas chromatography - mass spectrometry -

Beyond Endocasts: Using Predicted Brain-Structure Volumes of Extinct Birds to Assess Neuroanatomical and Behavioral Inferences

diversity Article Beyond Endocasts: Using Predicted Brain-Structure Volumes of Extinct Birds to Assess Neuroanatomical and Behavioral Inferences 1, , 2 2 Catherine M. Early * y , Ryan C. Ridgely and Lawrence M. Witmer 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Ohio University, Athens, OH 45701, USA 2 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Ohio University, Athens, OH 45701, USA; [email protected] (R.C.R.); [email protected] (L.M.W.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Current Address: Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA. y Received: 1 November 2019; Accepted: 30 December 2019; Published: 17 January 2020 Abstract: The shape of the brain influences skull morphology in birds, and both traits are driven by phylogenetic and functional constraints. Studies on avian cranial and neuroanatomical evolution are strengthened by data on extinct birds, but complete, 3D-preserved vertebrate brains are not known from the fossil record, so brain endocasts often serve as proxies. Recent work on extant birds shows that the Wulst and optic lobe faithfully represent the size of their underlying brain structures, both of which are involved in avian visual pathways. The endocasts of seven extinct birds were generated from microCT scans of their skulls to add to an existing sample of endocasts of extant birds, and the surface areas of their Wulsts and optic lobes were measured. A phylogenetic prediction method based on Bayesian inference was used to calculate the volumes of the brain structures of these extinct birds based on the surface areas of their overlying endocast structures. This analysis resulted in hyperpallium volumes of five of these extinct birds and optic tectum volumes of all seven extinct birds. -

The Avifauna of Mt. Karimui, Chimbu Province, Papua New Guinea, Including Evidence for Long-Term Population Dynamics in Undisturbed Tropical Forest

Ben Freeman & Alexandra M. Class Freeman 30 Bull. B.O.C. 2014 134(1) The avifauna of Mt. Karimui, Chimbu Province, Papua New Guinea, including evidence for long-term population dynamics in undisturbed tropical forest Ben Freeman & Alexandra M. Class Freeman Received 27 July 2013 Summary.—We conducted ornithological feld work on Mt. Karimui and in the surrounding lowlands in 2011–12, a site frst surveyed for birds by J. Diamond in 1965. We report range extensions, elevational records and notes on poorly known species observed during our work. We also present a list with elevational distributions for the 271 species recorded in the Karimui region. Finally, we detail possible changes in species abundance and distribution that have occurred between Diamond’s feld work and our own. Most prominently, we suggest that Bicolored Mouse-warbler Crateroscelis nigrorufa might recently have colonised Mt. Karimui’s north-western ridge, a rare example of distributional change in an avian population inhabiting intact tropical forests. The island of New Guinea harbours a diverse, largely endemic avifauna (Beehler et al. 1986). However, ornithological studies are hampered by difculties of access, safety and cost. Consequently, many of its endemic birds remain poorly known, and feld workers continue to describe new taxa (Prat 2000, Beehler et al. 2007), report large range extensions (Freeman et al. 2013) and elucidate natural history (Dumbacher et al. 1992). Of necessity, avifaunal studies are usually based on short-term feld work. As a result, population dynamics are poorly known and limited to comparisons of diferent surveys or diferences noticeable over short timescales (Diamond 1971, Mack & Wright 1996). -

Ancient Bird Bones Redate Human Activity in Madagascar by 6,000 Years 12 September 2018

Ancient bird bones redate human activity in Madagascar by 6,000 years 12 September 2018 first arrived in Madagascar 2,400-4,000 years ago. However, the new study provides evidence of human presence on Madagascar as far back as 10,500 years ago—making these modified elephant bird bones the earliest known evidence of humans on the island. Lead author Dr. James Hansford from ZSL's Institute of Zoology said: "We already know that Madagascar's megafauna—elephant birds, hippos, giant tortoises and giant lemurs—became extinct less than 1,000 years ago. There are a number of theories about why this occurred, but the extent of human involvement hasn't been clear. Disarticulation marks on the base of the tarsometatarsus. These cut marks were made when removing the toes from the foot. Credit: ZSL Analysis of bones, from what was once the world's largest bird, has revealed that humans arrived on the tropical island of Madagascar more than 6,000 years earlier than previously thought—according to a study published today, 12 September 2018, in the journal Science Advances. A team of scientists led by international conservation charity ZSL (Zoological Society of London) discovered that ancient bones from the This chop mark would have been made with a large extinct Madagascan elephant birds (Aepyornis and sharp tool. The clear straight line of the cut with no Mullerornis) show cut marks and depression continued cracks indicate the mark was made on fresh fractures consistent with hunting and butchery by bone and chopped into different cuts of meat. Credit: ZSL prehistoric humans. -

Recommended Band Size List Page 1

Jun 00 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme - Recommended Band Size List Page 1 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme Recommended Band Size List - Birds of Australia and its Territories Number 24 - May 2000 This list contains all extant bird species which have been recorded for Australia and its Territories, including Antarctica, Norfolk Island, Christmas Island and Cocos and Keeling Islands, with their respective RAOU numbers and band sizes as recommended by the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme. The list is in two parts: Part 1 is in taxonomic order, based on information in "The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories" (1994) by Leslie Christidis and Walter E. Boles, RAOU Monograph 2, RAOU, Melbourne, for non-passerines; and “The Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines” (1999) by R. Schodde and I.J. Mason, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, for passerines. Part 2 is in alphabetic order of common names. The lists include sub-species where these are listed on the Census of Australian Vertebrate Species (CAVS version 8.1, 1994). CHOOSING THE CORRECT BAND Selecting the appropriate band to use combines several factors, including the species to be banded, variability within the species, growth characteristics of the species, and band design. The following list recommends band sizes and metals based on reports from banders, compiled over the life of the ABBBS. For most species, the recommended sizes have been used on substantial numbers of birds. For some species, relatively few individuals have been banded and the size is listed with a question mark. In still other species, too few birds have been banded to justify a size recommendation and none is made. -

Baker2009chap58.Pdf

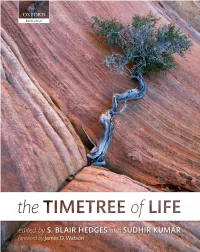

Ratites and tinamous (Paleognathae) Allan J. Baker a,b,* and Sérgio L. Pereiraa the ratites (5). Here, we review the phylogenetic relation- aDepartment of Natural Histor y, Royal Ontario Museum, 100 Queen’s ships and divergence times of the extant clades of ratites, Park Crescent, Toronto, ON, Canada; bDepartment of Ecology and the extinct moas and the tinamous. Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada Longstanding debates about whether the paleognaths *To whom correspondence should be addressed (allanb@rom. are monophyletic or polyphyletic were not settled until on.ca) phylogenetic analyses were conducted on morphological characters (6–9), transferrins (10), chromosomes (11, 12), Abstract α-crystallin A sequences (13, 14), DNA–DNA hybrid- ization data (15, 16), and DNA sequences (e.g., 17–21). The Paleognathae is a monophyletic clade containing ~32 However, relationships among paleognaths are still not species and 12 genera of ratites and 46 species and nine resolved, with a recent morphological tree based on 2954 genera of tinamous. With the exception of nuclear genes, characters placing kiwis (Apterygidae) as the closest rela- there is strong molecular and morphological support for tives of the rest of the ratites (9), in agreement with other the close relationship of ratites and tinamous. Molecular morphological studies using smaller data sets ( 6–8, 22). time estimates with multiple fossil calibrations indicate that DNA sequence trees place kiwis in a derived clade with all six families originated in the Cretaceous (146–66 million the Emus and Cassowaries (Casuariiformes) (19–21, 23, years ago, Ma). The radiation of modern genera and species 24). -

![January 2005] Reviews Trivers's Theory Of](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0144/january-2005-reviews-triverss-theory-of-490144.webp)

January 2005] Reviews Trivers's Theory Of

January 2005] Reviews 367 Trivers's theory of parent-offspring conflict associated fauna and flora, biotic history of has shed relatively little empirical light on sib- Australia, possible feeding habits, and the like. licide in birds will undoubtedly provoke some The book's concept, organization, and visual raised eyebrows. But Mock's perspectives are so presentation are brilliant, but the execution has clearly articulated and thoughtfully explained some serious flaws. that even readers with dissenting views will be The first known species, Dromornis australis, unlikely to object strenuously. was described in 1874 by Richard Owen, and I highly recommend this book to anyone inter- for almost a century and a quarter the drom- ested in the evolutionary biology of family con- ornithids were associated with paleognathous flict. It will be especially useful to ornithologists ratites such as emus and cassowaries. The name working on such topics as hatching asynchrony "mihirung" was originally adopted for these siblicide, brood reduction, and parental care. birds by Rich (1979) from Aboriginal traditions And for anyone wanting to know how to write of giant emus (mihirung paringmal) believed pos- a scholarly biological book that will appeal to a sibly to apply to Genyornis. It was not until the general audience. More Than Kin and Less Than seminal paper of Murray and Megirian (1998), Kind should be essential reading.•RONALD L. based on newly collected Miocene skull mate- MUMME, Department of Biology, Allegheny College, rial, that the anseriform relationships of the 520 North Main Street, Meadville, Pennsylvania Dromornithidae were revealed. Six years later, 16335, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Murray and Vickers-Rich glibly and rather mis- leadingly refer to these birds as gigantic geese and imply that their nonratite nature should have been apparent earlier. -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

/ Chapter 2 THE FOSSIL RECORD OF BIRDS Storrs L. Olson Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC. I. Introduction 80 II. Archaeopteryx 85 III. Early Cretaceous Birds 87 IV. Hesperornithiformes 89 V. Ichthyornithiformes 91 VI. Other Mesozojc Birds 92 VII. Paleognathous Birds 96 A. The Problem of the Origins of Paleognathous Birds 96 B. The Fossil Record of Paleognathous Birds 104 VIII. The "Basal" Land Bird Assemblage 107 A. Opisthocomidae 109 B. Musophagidae 109 C. Cuculidae HO D. Falconidae HI E. Sagittariidae 112 F. Accipitridae 112 G. Pandionidae 114 H. Galliformes 114 1. Family Incertae Sedis Turnicidae 119 J. Columbiformes 119 K. Psittaciforines 120 L. Family Incertae Sedis Zygodactylidae 121 IX. The "Higher" Land Bird Assemblage 122 A. Coliiformes 124 B. Coraciiformes (Including Trogonidae and Galbulae) 124 C. Strigiformes 129 D. Caprimulgiformes 132 E. Apodiformes 134 F. Family Incertae Sedis Trochilidae 135 G. Order Incertae Sedis Bucerotiformes (Including Upupae) 136 H. Piciformes 138 I. Passeriformes 139 X. The Water Bird Assemblage 141 A. Gruiformes 142 B. Family Incertae Sedis Ardeidae 165 79 Avian Biology, Vol. Vlll ISBN 0-12-249408-3 80 STORES L. OLSON C. Family Incertae Sedis Podicipedidae 168 D. Charadriiformes 169 E. Anseriformes 186 F. Ciconiiformes 188 G. Pelecaniformes 192 H. Procellariiformes 208 I. Gaviiformes 212 J. Sphenisciformes 217 XI. Conclusion 217 References 218 I. Introduction Avian paleontology has long been a poor stepsister to its mammalian counterpart, a fact that may be attributed in some measure to an insufRcien- cy of qualified workers and to the absence in birds of heterodont teeth, on which the greater proportion of the fossil record of mammals is founded. -

BIOLOGICAL SURVEY of KANGAROO ISLAND SOUTH AUSTRALIA in NOVEMBER 1989 and 1990

A BIOLOGICAL SURVEY OF KANGAROO ISLAND SOUTH AUSTRALIA IN NOVEMBER 1989 and 1990 Editors A. C. Robinson D. M. Armstrong Biological Survey and Research Section Heritage and Biodiversity Division Department for Environment, Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs, South Australia 1999 i Kangaroo Island Biological Survey The Biological Survey of Kangaroo Island, South Australia was carried out with the assistance of funds made available by, the Commonwealth of Australia under the 1989-90 National Estate Grants Programs and the State Government of South Australia. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the Australian Heritage Commission or the State Government of South Australia. The report may be cited as: Robinson, A. C. & Armstrong, D. M. (eds) (1999) A Biological Survey of Kangaroo Island, South Australia, 1989 & 1990. (Heritage and Biodiversity Section, Department for Environment, Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs, South Australia). Copies of the report may be accessed in the library: Environment Australia Department for Environment, Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs GPO Box 636 or 1st Floor, Roma Mitchell House CANBERRA ACT 2601 136 North Terrace, ADELAIDE SA 5000 EDITORS A.C. Robinson, D.M. Armstrong, Biological Survey and Research, Heritage &Biodiversity Section, Department for Environment Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs PO Box 1047 ADELAIDE 5001 AUTHORS D M Armstrong, P.J.Lang, A C Robinson, Biological Survey and Research, Heritage &Biodiversity Section, Department for Environment, Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs PO Box 1047 ADELAIDE 5001 N Draper, Australian Cultural Heritage Management Pty Ltd, 53 Hackney Rd. HACKNEY, SA 5069 G Carpenter, Biodiversity Monitoring and Evaluation, Heritage &Biodiversity Section, Department for Environment Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs. -

Grounded Birds in New Zealand

Flightless Grounded Birds in New Zealand An 8th Grade Research Paper By Nathaniel Roth Hilltown Cooperative Charter Public School June 2014 1 More than half of the birds in New Zealand either can’t fly, can only partially fly, or don’t like to fly. (Te Ara) This is a fact. Although only sixteen species in New Zealand are technically flightless, with another sixteen that are extinct (TerraNature), a majority of more than 170 bird species will not fly unless their lives are threatened, or not even then. This is surprising, since birds are usually known for flying. A flightless bird is a bird that cannot fly, such as the wellknown ostrich and emu, not to mention penguins. The two main islands southeast of Australia that make up New Zealand have an unusually diverse population of these birds. I am personally very interested in New Zealand and know a lot about it because my mother was born there, and I still have family there. I was very intrigued by these birds in particular, and how different they are from most of the world’s birds. I asked myself, why New Zealand? What made this tiny little country have so many birds that can’t fly, while in the rest of the world, hardly any live in one place? My research has informed me that the population and diversity of flightless birds here is so large because it has been isolated for so long from other land masses. Almost no mammals, and no land predators, lived there in the millions of years after it split from the Australian continent, so flying birds didn’t have as much of an advantage during this time. -

Genomic Signature of an Avian Lilliput Effect Across the K-Pg Extinction

Syst. Biol. 67(1):1–13, 2018 © The Author(s) 2017. Published by Oxford University Press, on behalf of the Society of Systematic Biologists. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: [email protected] DOI:10.1093/sysbio/syx064 Advance Access publication July 13, 2017 Genomic Signature of an Avian Lilliput Effect across the K-Pg Extinction ,∗, , , JACOB S. BERV1 † AND DANIEL J. FIELD2 3 † 1Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Cornell University, 215 Tower Road, Ithaca NY, 14853, USA; 2Department of Geology & Geophysics, Yale University, 210 Whitney Avenue New Haven, CT, 06511, USA; and 3Department of Biology and Biochemistry, Milner Centre for Evolution, University of Bath, Building 4 South, Claverton Down, Bath, BA2 7AY, UK ∗ Correspondence to be sent to: Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA; E-mail: [email protected]. †Jacob S. Berv and Daniel J. Field contributed equally to this work. Received 12 February 2017; reviews returned 03 July 2017; accepted 05 July 2017 Associate Editor: Simon Ho Abstract.—Survivorship following major mass extinctions may be associated with a decrease in body size—a phenomenon called the Lilliput Effect. Body size is a strong predictor of many life history traits (LHTs), and is known to influence demography and intrinsic biological processes. Pronounced changes in organismal size throughout Earth history are therefore likely to be associated with concomitant genome-wide changes in evolutionary rates. Here, we report pronounced heterogeneity in rates of molecular evolution (varying up to ∼20-fold) across a large-scale avian phylogenomic data set and show that nucleotide substitution rates are strongly correlated with body size and metabolic rate. -

A Molecular Phylogeny of the Solanaceae

TAXON 57 (4) • November 2008: 1159–1181 Olmstead & al. • Molecular phylogeny of Solanaceae MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS A molecular phylogeny of the Solanaceae Richard G. Olmstead1*, Lynn Bohs2, Hala Abdel Migid1,3, Eugenio Santiago-Valentin1,4, Vicente F. Garcia1,5 & Sarah M. Collier1,6 1 Department of Biology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195, U.S.A. *olmstead@ u.washington.edu (author for correspondence) 2 Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112, U.S.A. 3 Present address: Botany Department, Faculty of Science, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt 4 Present address: Jardin Botanico de Puerto Rico, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Apartado Postal 364984, San Juan 00936, Puerto Rico 5 Present address: Department of Integrative Biology, 3060 Valley Life Sciences Building, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720, U.S.A. 6 Present address: Department of Plant Breeding and Genetics, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853, U.S.A. A phylogeny of Solanaceae is presented based on the chloroplast DNA regions ndhF and trnLF. With 89 genera and 190 species included, this represents a nearly comprehensive genus-level sampling and provides a framework phylogeny for the entire family that helps integrate many previously-published phylogenetic studies within So- lanaceae. The four genera comprising the family Goetzeaceae and the monotypic families Duckeodendraceae, Nolanaceae, and Sclerophylaceae, often recognized in traditional classifications, are shown to be included in Solanaceae. The current results corroborate previous studies that identify a monophyletic subfamily Solanoideae and the more inclusive “x = 12” clade, which includes Nicotiana and the Australian tribe Anthocercideae. These results also provide greater resolution among lineages within Solanoideae, confirming Jaltomata as sister to Solanum and identifying a clade comprised primarily of tribes Capsiceae (Capsicum and Lycianthes) and Physaleae.