Staten Island Cemeteries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RETROSPECTIVE BOOK REVIEWS by Esley Hamilton, NAOP Board Trustee

Field Notes - Spring 2016 Issue RETROSPECTIVE BOOK REVIEWS By Esley Hamilton, NAOP Board Trustee We have been reviewing new books about the Olmsteds and the art of landscape architecture for so long that the book section of our website is beginning to resemble a bibliography. To make this resource more useful for researchers and interested readers, we’re beginning a series of articles about older publications that remain useful and enjoyable. We hope to focus on the landmarks of the Olmsted literature that appeared before the creation of our website as well as shorter writings that were not intended to be scholarly works or best sellers but that add to our understanding of Olmsted projects and themes. THE OLMSTEDS AND THE VANDERBILTS The Vanderbilts and the Gilded Age: Architectural Aspirations 1879-1901. by John Foreman and Robbe Pierce Stimson, Introduction by Louis Auchincloss. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991, 341 pages. At his death, William Henry Vanderbilt (1821-1885) was the richest man in America. In the last eight years of his life, he had more than doubled the fortune he had inherited from his father, Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877), who had created an empire from shipping and then done the same thing with the New York Central Railroad. William Henry left the bulk of his estate to his two eldest sons, but each of his two other sons and four daughters received five million dollars in cash and another five million in trust. This money supported a Vanderbilt building boom that remains unrivaled, including palaces along Fifth Avenue in New York, aristocratic complexes in the surrounding countryside, and palatial “cottages” at the fashionable country resorts. -

Descendants of Nicola MAZZONE and Grazia TRIMARCO

Descendants of Nicola MAZZONE and Grazia TRIMARCO First Generation 1. Nicola MAZZONE was born about 1772 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy and died before 1864 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy. Nicola married Grazia TRIMARCO about 1795 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy. Grazia was born about 1775 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy and died before Feb 1876 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy. Children of Nicola MAZZONE and Grazia TRIMARCO were: 2 F i. Maria MAZZONE was born about 1798 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy and died Jan 28, 1866 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy about age 68. 3 F ii. Rachele MAZZONE was born about 1806 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy and died Feb 28, 1876 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy about age 70. 4 M iii. Vito MAZZONE was born about 1809 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy and died Mar 28, 1890 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy about age 81. 5 M iv. Vincenzo MAZZONE was born about 1812 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy and died Feb 11, 1891 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy about age 79. 6 M v. Michele MAZZONE was born Feb 10, 1814 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy and died May 30, 1893 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy at age 79. Second Generation 2. Maria MAZZONE was born about 1798 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy and died Jan 28, 1866 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy about age 68. Maria married Nicola TRIMARCO, son of Sabato TRIMARCO and Giovanna SESSA. Nicola was born about 1791 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy and died Jun 16, 1871 in Senerchia, Avellino, Campania, Italy about age 80. -

The Vanderbilts and the Story of Their Fortune

Ml' P WHi|i^\v^\\ k Jll^^K., VI p MsW-'^ K__, J*-::T-'7^ j LIBRARY )rigliam i oiMig U mversat FROM. Call Ace. 2764 No &2i?.-^ No ill -^aa^ceee*- Britfham Voung il/ Academy, i "^ Acc. No. ^7^V ' Section -^^ i^y I '^ ^f/ Shelf . j> \J>\ No. ^^>^ Digitized by tine Internet Arcinive in 2010 witii funding from Brigiiam Young University littp://www.arcliive.org/details/vanderbiltsstoryOOcrof -^^ V !<%> COMMODORE VANDERBILT. ? hr^ t-^ ^- -v^' f ^N\ ^ 9^S, 3 '^'^'JhE VANDERBILTS THE STORY OF THEIR FORTUNE BT W. A. CKOFFUT A0THOR OF "a helping HAND," "A MIDSUMMER LARK," "THE BOUKBON BALLADS," " HISTOBr OF CONNECTICUT," ETC. CHICAGO AND NEW YORK BELFOBD, CLARKE & COMPANY Publishers 1/ COPYKIGHT, 1886, BY BELFORD, CLAEKE & COMPANY. TROWS PRINTING AND BOOKBINDING COMPANY, NEW YORK. PREFACE This is a history of the Yanderbilt family, with a record of their vicissitudes, and a chronicle of the method by which their wealth has been acquired. It is confidently put forth as a work which should fall into the hands of boys and young men—of all who aspire to become Cap- tains of Industry or leaders of their fellows in the sharp and wholesome competitions of life. In preparing these pages, the author has had an am- bition, not merely to give a biographical picture of sire, son, and grandsons and descendants, but to consider their relation to society, to measure the significance and the influence of their fortune, to ascertain where their money came from, to inquire whether others are poorer because they are rich, whether they are hindering or promoting civilization, whether they and such as they are impediments to the welfare of the human i-ace. -

In Cases Where Multiple References of Equivalent Length Are Given, the Main Or Most Explanatory Reference (If There Is One) Is Shown in Bold

index NB: In cases where multiple references of equivalent length are given, the main or most explanatory reference (if there is one) is shown in bold. 9/11 Memorial 25 81–82, 83, 84 9/11 “people’s memorial” 40 Ammann, Othmar H. Abbott, Mabel 99 (1879–1965) 151, 152, Abolitionists on Staten 153, 155 Island 30, 167–68 Anastasia, Albert 197 Abraham J. Wood House 49 Andrew J. Barberi, ferry 60, Adams, John 163, 164, 165 246 African American com- Andros, Sir Edmund 234 munities 34, 75, 78ff, Angels’ Circle 40 176–77, 179 Arthur Kill 19, 37, 74, 76, African Methodist Episcopal 117, 119, 148, 149, 164, Zion Church (see A.M.E. 206 Zion) Arthur Kill Lift Bridge Akerly, Dr. Samuel 107 148–49 Almirall, Raymond F. Arthur Kill Salvage Yard 38 (1869–1939) 204 Asians on Staten Island 36, Ambrose Channel 90, 92 37 American Magazine 91 Atlantic Salt 29 American Society of Civil Austen, Alice 126–134, Engineers 152 201, 209, 242; (grave of) A.M.E. Zion Church 80, 43 248 index Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing- Boy Scouts 112 Room Companion 76 Breweries 34, 41, 243 Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Bridges: 149, 153 Arthur Kill Lift 148–49 Barnes, William 66 Bayonne 151–52, 242 Battery Duane 170 Goethals 150, 241 Battery Weed 169, 170, Outerbridge Crossing 150, 171–72, 173, 245 241 Bayles, Richard M. 168 Verrazano-Narrows 112, Bayley-Seton Hospital 34 152–55, 215, 244 Bayley, Dr. Richard 35, 48, Brinley, C. Coapes 133 140 British (early settlers) 159, Bayonne Bridge 151–52, 176; (in Revolutionary 242 War) 48, 111, 162ff, 235 Beil, Carlton B. -

VANDERBILT MAUSOLEUM, Staten Island

Landmarks Preservation Commission April 12, 2016, Designation List 487 LP-1208 VANDERBILT MAUSOLEUM, Staten Island Built: c. 1884-87; Richard Morris Hunt, architect; F. L. & J. C. Olmsted, landscape architects; John J. R. Croes, landscape engineer Landmark Site: Borough of Staten Island, Tax Map Block 934, Lot 250 in part, consisting of the entire mausoleum, its steps, and retaining walls; the hillock enclosing the mausoleum; the terrace in front of the mausoleum’s main facade and the base and walls of the terrace; the pathway leading from the terrace northeasterly, southeasterly, southwesterly, and southeasterly, beneath the arch near the southernmost entrance to the lot, to the lot boundary; the entrance arch and gates, and the adjoining stone retaining walls extending from the south face and sides of the arch northeasterly and southwesterly to the north and south lot lines; the stone retaining walls extending from the north face of the arch along both sides of a portion of the pathway; the land beneath the opening in the entrance arch; and the land upon which these improvements are sited. On September 9, 1980, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Vanderbilt Mausoleum and Cemetery and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. A representative of the trustees overseeing the property testified in opposition to the proposed designation. A representative of New Dorp Moravian Church also testified in opposition to the proposed designation. Two people spoke in favor of the proposed designation, including a representative of the Preservation League of Staten Island. -

THE Westflild LEADER the Leading and Mott Widely Circulated Weekly Nempaper in Union County ITY-SIXTH YEAR—No

THE WESTFliLD LEADER The Leading And Mott Widely Circulated Weekly Nempaper In Union County ITY-SIXTH YEAR—No. 43 PublUhed WESTFIELD, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, JULY 5, 1956 Every Thurtjda; 30 r«g••—i Onto fret Weiek Registration Memorial Library An Unwilling Contetlant Attendance to Decide To Close Saturdays If Skating Continue* Lincoln School Th. W^rt^UI M...H.1 The free roller skating program Playfields Hits 2,380 Library will b. d..W S.tyr- at the South avenue municipal imj, Jvriaf July «»4 Av«a>l. parking lot will continue through- Th* r*(al>r 9 «... to S p.m. out the summer if large attend- wkWvU •• Sitvr4*r will U ances continue, the Recieation Principal Resigns ice At nnimmi Saturday, i»ft, «. Commission has announced. The I programs are held every Friday [Time High Of evening. There were 165 teen- j Supermarket ageis pretent last week. H. M. Partington 1 Children Appeal Filed Library Plans In Local Systen mtion on the local play- [reached 2,380 at the end of Board Asked To For 28 Years Irrt. week of an eigkt-wetV Reading Project |am. Lincoln and Mfcraon Set Aflde Permit lead In registration* with Hillla M. Partinirton, « princi- thtj) 4D0 on each ground. Charles A. Keid Jr., attorney Will Be Offered pal in the Westfteld public schaoji Y<sk\y attendance «ra« at «n for the newly-formed Westfleld To Teen-Agen. for the past 2% )•««••, has re- Residents Association, filed an ap signed, effective Oct, 1, l»5g, MI ne hifh «• » total at more principal of Lincoln fkfcool to ac-^', 10,#W children m retched. -

Rahul Gandhi

Kesri- The Battle Friday 22 March to 28 March 2019 1 of Saragarhi Voice of South Asian Community Since March 2002 Page 29 Vol. 15 Issue 43 Friday 22 March to 28 March 2019 $1 www.thesouthasianinsider.com [email protected] Why Terrorists Kill? The striking similarities between the New Zealand and Pulse nightclub shooters (Insider Bureau)- The decision to in ISIS and never traveled to Iraq kill innocent civilians who are or Syria where ISIS was strangers -- whether you are a headquartered. His radicalization jihadist terrorist or a white was entirely driven by what he nationalist militant -- can never viewed on the internet. be easily explained, but there Similarly, Brenton Tarrant, the does seem to be a common terrorist who allegedly carried out profile for "lone actor" Western the New Zealand attacks, killing terrorists today, irrespective of 50 people, tapped into a large their ideology. library of white nationalist First, they are radicalizing material from around the world because of what they read on the internet, according to the online. ISIS created a vast document that Tarrant posted global library of propaganda that about his motivations for the influenced terrorists such as attacks. Omar Mateen, who killed 49 Tarrant's heroes were right-wing people in the Pulse nightclub in terrorists from around the West: Orlando, Florida, in June 2016. Mateen never met with anyone Page 19 Indian General Election, 2019 The world's happiest countries The Indian electorate is not easily swayed by terrorism (Insider Bureau) - Elections bring on a manthan churn of governance discourse in a democratic polity. -

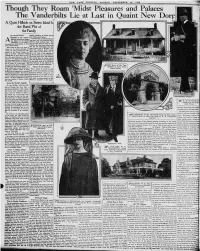

The Vanderbilts Lie at Last in Quaint New Dorp

Though They Roam 'Midst Pleasures and Palaces The Vanderbilts Lie at Last in Quaint New Dorp A Quiet Hillside on Statten Island Is the Burial Plot of the Family By Arnold Prince similar residence on Fifth Avenue ANOTHER of the Vander- and Fifty-second Street. bilts has been placed beside Cornelius was an aristocratic look¬ his fathers in the family ing man, with fair features and a mausoleum in the placid, narrow, finely modeled head. But inconspicuous little hamlet of New for the fact that he wore no side Dorp, Staten Island. whiskers he would have looked much like the old and this When alive he in a sense, a Commodore, was, may be said also of William. Wil¬ citizen of the world, although, of liam never severed his alle¬ was, perhaps, better looking course, he than either of giance to the United States, the the others, and, in land of his birth. His great wealth fact, had little of the appearance of the business man and enabled him to move about at wilL. financier. He looked more like a man For this good fortune he was in¬ destined the thrift and of for society than the money marts, debted to energy and this his sturdy grandfather of Dutch an¬ impression was heightened tecedents, who piled up an amazing by the slight wave of his abundant lot of in a few years. He hair, the part in the middle of it, money and the smooth was able to go where he liked, and fresh, complexion. home of the Van- he liked the interesting places. -

BILTMORE ESTATE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 BILTMORE ESTATE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Biltmore Estate (Additional Documentation and Boundary Reduction) Other Name/Site Number: N/A 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Generally bounded by the Swannanoa River on the north, the Not for publication: N/A paths of NC 191 and I-26 on the west, the paths of the I-25 and the Blue Ridge Parkway on the south, and a shared border with numerous property owners on the east; One Biltmore Plaza. City/Town: Asheville Vicinity: X State: NC County: Buncombe Code: 021 Zip Code: 28801 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): ___ Public-Local: District: X_ Public-State: Site: ___ Public-Federal: Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 56 buildings 57 buildings 31 sites 25 sites 51 structures 30 structures 0 objects 0 objects 138 Total 112 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: All Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 BILTMORE ESTATE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Download the Newspaper This Week (Pdf)

Ad Populos, Non Aditus, Pervenimus USPS 680020 Published Every Thursday OUR 111th YEAR – ISSUE NO. 26-111 Periodical – Postage Paid at Westfield, N.J. Thursday, March 8, 2001 Since 1890 (908) 232-4407 FIFTY CENTS Westfield Y Pulling Out As First Night Organizer By MICHELLE H. LEPOIDEVIN the five years, was an absolute reaf- ship, schools and printing facilities, AND PAUL J. PEYTON Specially Written for The Westfield Leader firmation that First Night Westfield and countless hours offered by vol- was worth every bit of the effort that unteers. Temple Emanu-El has also After five successful years, was put into it,” stated Ms. Black, in been the site for First Night Westfielders may have to find a new a detailed letter released last Friday Westfield’s major fundraising event, venue to ring in the new year follow- by the Y. Taste of Westfield. ing a decision this week by the “We always tried to raise approxi- “We would spend $45-$50,000 on Westfield Y that it will no longer be mately $80,000,” Ms. Black told The entertainment,” she said, “other organizing First Night Westfield. Westfield Leader. money would be spent on paper prod- Organizers said the decision to no Fundraising efforts, Ms. Black ucts. We’ve been very frugal with longer run the event was based on an explained, involve numerous enti- what we spend,” said Ms. Black. inability to attract a sufficient number ties such as Westfield houses of wor- CONTINUED ON PAGE 10 of volunteers to man the multi-fac- eted event and not any lack of interest on the part of the Westfield commu- nity. -

Handouts 1-3

Handouts 1-3 AMERICAN INDUSTRIALISTS: ROBBER BARONS OR CAPTAINS OF INDUSTRY? American Industrialization Outline • Industrialization and Big Business – New technology/inventions sets stage for industrial growth in America after 1850 – Big Business leaders John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, Cornelius Vanderbilt and J.P. Morgan are viewed in two ways: • Captains of industry – Served the United States positively, created jobs – Philanthropists-giving to charities, founding libraries and museums • Robber barons – Built fortunes from exploiting workers – Drained the United States’s natural resources – Social Darwinism—Big Business men justified what they did by Darwin’s theory of evolution “only the strong survive” – Federal Government—laissez-faire policies, government hands off of business practices and people, no regulations – Creating a Big Business • Monopoly: buying out competitors in same business, prices rise (only one choice) • Trust: similar businesses turning over assets to a board to control prices and competition. • Consolidation: creating huge businesses controlled by one company (vertical integration and horizontal integration) – Some Americans believed Big Business was bad, that it didn’t protect workers and consumers. Federal Government begins to interfere: • Sherman Anti-Trust Act 1890: Law passed to restrict creations of big businesses. Began breaking big companies up. American Industrialization Meet Andrew Carnegie The Two Andrews Generous and naïve, while often grasping and ruthless, Andrew Carnegie personally embodied the contradictions that divided America in the Gilded Age. At a time when America struggled—often violently—to sort out the competing claims of democracy and individual gain, Carnegie championed both. He saw himself as a hero of working people, yet he crushed their unions. -

REPORT REAL ESTATE City’S Construction Industry

20120116-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 1/13/2012 7:30 PM Page 1 INSIDE IF YOU DO JUST ONE THING, TOP STORIES GUV... Hey, Mitt: Michael Make it pension Gross tries to fire reform, says Carol his health insurer ® Kellermann PAGE 4 PAGE 14 Jones Group struggling VOL. XXVIII, NO. 3 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM JANUARY 16-22, 2012 PRICE: $3.00 to find the right fit PAGE 3 Tick, tick, Daily News to Post: tick for Drop dead. Tabloid war back on in NYC Bloomie’s PAGE 3 Why tech, media legacy crave Hudson Sq. PAGE 4 Mayor eyes schools, A juicy case of jobs in his final two insider trading years; other gains IN THE MARKETS, PAGE 6 are set in stone Arianna Huffington meets Al-Jazeera BY JEREMY SMERD NEW YORK, NEW YORK, P. 8 Ed Koch restored the city’s fiscal health. Rudy Giuliani curbed crime. What will Mayor Michael Bloomberg be remembered for? There is, of course, no single an- swer—at least not yet. For the mayor, that is good news. He still has two years to write his administration’s final chapters and deliver on goals that have eluded him. And he made clear in his State of the City address last week that A CLASS BY HIMSELF: he plans to stay focused on his major Joseph Ficalora has taken priorities:education and economic de- his NY Community Bancorp velopment. BUSINESS LIVES from total obscurity to one of the nation’s top 40. “We don’t walk away from things,” he told Crain’s.