The Status of Attachment Theory in Psychoanalytic Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vaverová, Vladislava (520369)

1 UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK IN PRAGUE Department of Psychology The Effect of Infidelity in the Workplace on Life Satisfaction among Different Attachment Styles Master Thesis Supervisor: Submitted by: Vartan Agopian, PhD. Vladislava Vaverová Prague, April 2021 2 Declaration I hereby declare that I wrote this thesis individually based on literature and resources stated in references section. In Prague: 26 April 2021 Signature: 3 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my thesis supervisor, Dr. Vartan Agopian greatly for his support and guidance in completing this thesis with me. Words cannot express how much I owe him for his constant encouragement and motivation throughout this journey. Special thanks to my partner and family and friends for supporting me mentally and emotionally throughout the journey in finishing this thesis. 4 Abstract This study was designed to examine the effect of infidelity in the workplace on life satisfaction among different attachment styles. Specifically, this research investigated the effects of group of people working in corporate companies and their life satisfaction and infidelity in workplace. The study also examined the significant differences of infidelity and different attachment styles. One hundred and twenty-six participants attended to fill up the questionnaires to measure the effect of infidelity with adult attachment style and life satisfaction. The goal of this research was to find out relationship, connection, and the effect of infidelity on life satisfaction. Results showed that higher scores of secure attachments will predict higher levels of life satisfaction, while higher scores of anxious attachments will predict lower levels of life satisfaction, they also confirmed that infidelity and anxious attachment style will predict lower life satisfaction. -

PDF Download Mistress of Marymoor: Historical Romance At

MISTRESS OF MARYMOOR: HISTORICAL ROMANCE AT ITS VERY BEST PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anna Jacobs | 214 pages | 15 Nov 2013 | Createspace | 9781493778508 | English | United States Mistress of Marymoor: Historical Romance at Its Very Best PDF Book With no hope of a future otherwise, Deborah consents and soon after becomes owner of the estate when her benefactor dies. Error rating book. Daniel is not yet settled and is experiencing trauma from his wartime experiences. Joanna rated it it was amazing Feb 19, Anna Jacobs has 87 novels published as of April Simpson rated it really liked it Feb 24, Book list Series list Book covers. Family dramas and all their complications unfold amidst the dales of Lancashire…When her unfaithful husband dies in a car crash, Laura decides to leave Australia for her native England to help nurse her ailing mother. Please enter a number less than or equal to 3. Deborah knows that if she agrees she can save her mother and her elderly maid from the clutches of her uncle , but this is an huge step to take. Author Info. Other Editions 9. But trouble soon befalls the couple in the form of Anthony Elkin , who claims that the Marymoor estate rightly belongs to him. This collection of stand-alone short stories is a treat for new readers and dedicated fans alike. Unlike her cousin Susannah, she's only putting up with this London season because she promised her dying mother X Previous image. Returns policy. Ridge Hill. Yes, it's been told before in many versions,but it's still exciting to read again. -

The Role of the French Maîtresse En Titre: How Royal Mistresses Utilized Liminal Space to Gain Power and Access by Marine Elia

The Role of the French Maîtresse en titre: How Royal Mistresses Utilized Liminal Space to Gain Power and Access By Marine Elia Senior Honors Thesis Romance Studies University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 4/19/2021 Approved: Jessica Tanner, Thesis Advisor Valérie Pruvost, Reader Dorothea Heitsch, Reader 2 Table of Contents Introduction…Page 3 Chapter 1: The Liminal Space of the Maîtresse-en-titre…Page 15 Cahpter 2: Fashioning Power…Page 24 Chapter 3: Mistresses and Celebrity…Page 36 Conclusion…Page 52 Bibliography…Page 54 Acknowledgments…Page 58 3 Introduction Beginning in the mid-fifteenth century, during the reign of Charles VII (1422- 1461), the “royal favorite” (favorite royale) became a quasi-official position within the French royal court (Wellman 37). The royal favorite was an open secret of French courtly life, an approved, and sometimes encouraged, scandal that helped to define the period of a king's reign. Boldly defying Catholic tenants of marriage, the position was a highly public transgression of religious mores. Shaped during the Renaissance by powerful figures such as Diane de Poitiers and Agnès Sorel, the role of the royal mistress evolved through the centuries as each woman contributed their own traditions, further developing the expectations of the title. Some used their influence to become powerful political actors, often surpassing that of the king’s ministers, while other women used their title to patronize the arts. Using the liminal space of their métier, royal mistresses created opportunities for themselves using the limited spaces available to women in Ancien Régime France. Historians and writers have been captivated by the role of the royal mistress for centuries, studying their lives and publishing both academic and non-academic biographies of individual mistresses. -

The Self in Understanding and Treating Psychological Disorders Edited by Michael Kyrios, Richard Moulding, Guy Doron, Sunil S

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-07914-4 - The Self in Understanding and Treating Psychological Disorders Edited by Michael Kyrios, Richard Moulding, Guy Doron, Sunil S. Bhar,Maja Nedeljkovic and Mario Mikulincer Frontmatter More information The Self in Understanding and Treating Psychological Disorders © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-07914-4 - The Self in Understanding and Treating Psychological Disorders Edited by Michael Kyrios, Richard Moulding, Guy Doron, Sunil S. Bhar,Maja Nedeljkovic and Mario Mikulincer Frontmatter More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-07914-4 - The Self in Understanding and Treating Psychological Disorders Edited by Michael Kyrios, Richard Moulding, Guy Doron, Sunil S. Bhar,Maja Nedeljkovic and Mario Mikulincer Frontmatter More information The Self in Understanding and Treating Psychological Disorders Edited by Michael Kyrios Research School of Psychology, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia Richard Moulding School of Psychology, Deakin University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia Guy Doron The Baruch Ivcher School of Psychology, Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya, Herzliya, Israel Sunil S. Bhar Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, VIC, Australia Maja Nedeljkovic Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, VIC, Australia Mario Mikulincer Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya and Baruch Ivcher School of Psychology, Herzliya, Israel © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-07914-4 - The Self in Understanding and Treating Psychological Disorders Edited by Michael Kyrios, Richard Moulding, Guy Doron, Sunil S. Bhar,Maja Nedeljkovic and Mario Mikulincer Frontmatter More information University Printing House, Cambridge CB2 8BS, United Kingdom Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. -

Pennsylvania Common Law Marriage and Annulment: Present Law and Proposals for Reform

Volume 15 Issue 1 Article 7 1969 Pennsylvania Common Law Marriage and Annulment: Present Law and Proposals for Reform Steven G. Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Family Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven G. Brown, Pennsylvania Common Law Marriage and Annulment: Present Law and Proposals for Reform, 15 Vill. L. Rev. 134 (1969). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol15/iss1/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Brown: Pennsylvania Common Law Marriage and Annulment: Present Law and P VILLANOVA LAW REVIEW [VOL. 15 PENNSYLVANIA COMMON LAW MARRIAGE AND ANNULMENT: PRESENT LAW AND PROPOSALS FOR REFORM I. INTRODUCTION Although the institution of marriage is age-old, as societal values and structures change, it is incumbent upon the law to keep pace with these changes. There has been a movement in Pennsylvania over the past 8 years to modify the existing marriage and divorce laws so that they may more adequately reflect a recognition of the current problems in the delicate areas of creation and termination of marriage. It is the purpose of this Comment to examine the existing law and the proposed changes in two important areas - Common Law Marriage and Annulment. II. COMMON LAW MARRIAGES A. Requirements A common law marriage is brought about through an agreement of the parties and absent a ceremony or a license.' At the present time such marriages are recognized as valid in Pennsylvania. -

My Favourite Painting Monty Don a Woman Bathing in a Streamby

Source: Country Life {Main} Edition: Country: UK Date: Wednesday 16, May 2018 Page: 88 Area: 559 sq. cm Circulation: ABC 41314 Weekly Ad data: page rate £3,702.00, scc rate £36.00 Phone: 020 7261 5000 Keyword: Paradise Gardens My favourite painting Monty Don A Woman Bathing in a Stream by Rembrandt Monty Don is a writer, gardener and television presenter. His new book Paradise Gardens is out now, published by Two Roads i My grandfather took me to an art gallery every school holidays and, as my education progressed, we slowly worked our way through the London collections. Rembrandt, he told me, was the greatest artist who had ever lived. I nodded, but was uncertain on what to look for that would confirm that judgement. Then I saw this painting and instantly knew. The subject-almost certainly Rembrandt's common-law wife, Hendrickje Stoffels— is not especially beautiful nor has a body or demeanour that might command especial attention. But, as she lifts the hem of her shift to wade in the water, she is made transcendent by Rembrandt's genius. In this, the simplest of moments by an ordinary person in a painting that is hardly more than a sketch, Rembrandt has captured human love at its most 1 intimate and tender. And there is no A Woman Bathing in a Stream, 1654, by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-69), 24 /4in 1 more worthy subject than that ? by 18 /2in, National Gallery, London John McEwen comments on^4 Woman Bathing in a Stream Geertje Dircx, Titus's nursemaid, became her church. -

Healing Factors in Guided Affective Imagery: a Qualitative Meta-Analysis

Healing Factors in Guided Affective Imagery: A Qualitative Meta-Analysis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a concentration in Psychology and a specialization in Counseling and Psychotherapy at the Union Institute & University Cincinnati, Ohio Elaine Sue Kramer April 3, 2010 Core Faculty: Lawrence J. Ryan, PhD i Abstract This qualitative meta-analysis compares and contrasts European and American approaches to Guided Affective Imagery (GAI). From a comparative review of literature of the European and American approaches, it is observed that there are noteworthy differences in how GAI is understood in theory and applied in practice. In the United States, GAI is not perceived as a method of deep psychotherapeutic intervention for neurotic disorders by most practitioners. In Europe, GAI is one of the more prevalent intervention techniques that has been reported to be effective in many disorders. Secondly, this meta-analysis seeks to identify the essential healing elements of GAI as they are implemented in psychotherapy. Twelve factors are identified from the literature. Of fundamental clinical importance is the activation of a patient’s “resources,” the positive characteristics of an individual that can be accessed to reinforce the patient’s ability to deal with a past traumatic experience. GAI provides the imagery context by which the patient may re-experience the trauma. The therapist assists by encouraging the patient to repeatedly utilize internal resources to confront the fearful event. Lasting relief may be conceptualized as repeated resource activation leading to a biochemically-induced remapping at synaptic sites away from the limbic-centered, emotion-based neural path associated with the traumatic event toward the prefrontal cortex-centered, cognitive-based path of appropriate behavior. -

The Devil's Mistress

1 THE DEVIL’S MISTRESS Genre: Historical tragedy Playwright: Brenda Love Zejdl This script is copyright protected and may not be reproduced, distributed or disseminated without the prior written permission of the author. Contact Information: Email: [email protected] Address: Dusni 1/928, Prague 11000, Czech Republic Cell phone: 011 (420) 739.078.229 Skype: brendazejdl The Devil’s Mistress 2 THE DEVIL’S MISTRESS SYNOPSIS: This play is inspired by actual incidents from 1620. Acts I and III are set in a prison in Leonberg, Germany and Act II takes place in the Prague castle. KATHARINA is the mother of the King’s Chief Mathematician, JOHANNES KEPLER. She is imprisoned in a dungeon and pressured to confess to witchcraft; first by treachery and then by intimidation through being shown torture instruments used on another woman while her son debates the validity of witchcraft trials with JEAN BODIN, the leading demonologist of that time, (in reality Bodin died in 1596, over 20 years before and never met Kepler). The result of this debate will determine her fate: freedom, torture or execution. This is an expose filled with the political intrigues and corruption that existed during these witch trials. CAST OF CHARACTERS: [7-8 actors needed if 2 can double, 2 women & 6 men] KATHARINA KEPLER: [60+ yrs old] Johanne Kepler’s mother, an herbalist unjustly jailed for witchcraft. Pious, and disliked by people in her village for meddling and insolence. JOHANNES KEPLER: [40-50yrs old]- Kepler was a slight man with a goatee, wears a dark suit with a starched ruff collar; he was slightly stooped from bending over his calculations and he squinted from bad eyesight. -

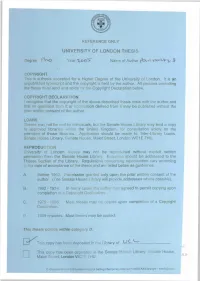

University of London Thesis

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree f*Vvo Year Name of Author A £ C O P Y R IG H T This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOANS Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the Senate House Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: Inter-Library Loans, Senate House Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the Senate House Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The Senate House Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962-1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. -

Separation, Adultery, Children Born out of Wedlock

COI QUERY Country of Origin Philippines Main subject Separation, adultery, children born out of wedlock Question(s) 1) Legal framework of divorce in the Philippines, and its implementation/enforcement in practice; 2) Legal framework of adultery in the Philippines, and its implementation/enforcement in practice; 3) Societal consequences of adultery; 4) Separation Agreements in the Philippines and their legal effects; 5) Legal status of children born out of the wedlock and/or as result of adultery; 6) Societal attitude towards a child born out of wedlock and/or as result of adultery Date of completion 6 March 2020 Query Code Q5-2020 Contributing EU+ COI n/a units (if applicable) Disclaimer This response to a COI query has been elaborated according to the Common EU Guidelines for Processing COI and EASO COI Report Methodology. The information provided in this response has been researched, evaluated and processed with utmost care within a limited time frame. All sources used are referenced. A quality review has been performed in line with the above mentioned methodology. This document does not claim to be exhaustive neither conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to international protection. If a certain event, person or organisation is not mentioned in the report, this does not mean that the event has not taken place or that the person or organisation does not exist. Terminology used should not be regarded as indicative of a particular legal position. The information in the response does not necessarily reflect the opinion of EASO and makes no political statement whatsoever. The target audience is caseworkers, COI researchers, policy makers, and decision making authorities. -

Viewing the Group Through the Lens of Attachment Theory

Secure Attachment Creates Bold Explorers: viewing the group through the lens of Attachment theory Jean Mehrtens RPN, BA, DipEd, MAppSci A Thesis presented to the Board of Examiners of the Australian and New Zealand Psychodrama Association Inc. in partial fulfilment of the requirement for certification as a Psychodramatist Copyright Statement This thesis has been completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements toward certification as a practitioner by the Board of Examiners of the Australian and New Zealand Psychodrama Association Incorporated. It represents a considerable body of work undertaken with extensive supervision. This knowledge and insight has been gained through hundreds of hours of experience, study and reflection. © Australian and New Zealand Psychodrama Association Incorporated 2008 Copyright is held by the author. The Australian and New Zealand Psychodrama Association Incorporated has the license to publish. All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission from the author and/or the Australian and New Zealand Psychodrama Association Incorporated. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise, save with written permission of the Australian and New Zealand Psychodrama Association Incorporated and/or the author. The development, preparation and publication of this work have been undertaken with great care. However, the publisher is not responsible for any errors contained herein or for consequences that may ensue from use of materials or information contained in this work. -

Psychotherapy for Borderline Personality Disorder: Where Do We Go from Here?

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by UCL Discovery Psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Where do we go from here? Peter Fonagy, Patrick Luyten, Anthony Bateman Submitted to: JAMA Psychiatry Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is one of the most prevalent, and most disabling, personality disorders. There is increasing consensus that the disorder is characterized by three related core features: severe emotion dysregulation, strong impulsivity, and social- interpersonal dysfunction.1 Individuals diagnosed with BPD were historically considered to be “hard to reach” and pessimism with regard to treatment prevailed. This view has changed over the past two decades, mainly as a result of emerging evidence for the efficacy and cost- effectiveness of specialized psychotherapies for individuals with BPD.2,3 The study by Cristea and colleagues4 in this issue represents a new and major leap forward in this regard, as it heralds the coming of age of research on the effectiveness of psychotherapy for BPD. Cristea et al. report a meta-analysis including 33 studies of specialized psychotherapy either as a standalone treatment or as an add-on to non-specialized psychotherapies in adult patients diagnosed with BPD. Overall, specialized psychotherapy emerges as moderately more effective than non-specialized psychotherapy in reducing borderline-relevant and other outcomes, such as general psychopathology and service utilization, with no differences between specialized psychotherapy as a standalone or as an add-on to usual treatment. Importantly, these effects were typically maintained up to 2-year follow-up. Very few adverse events were reported, suggesting that psychotherapy for BPD is both effective and safe.