Especially in Vizag and Kakinada, Has Caused Pollution Along the East Coast. Information on the Industrial Growth Occurring in T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping Land Subsidence of Krishna – Godavari Basin Using Persistent Scatterer Interferometry Technique

Mapping Land Subsidence of Krishna – Godavari Basin using Persistent Scatterer Interferometry Technique Lokhande Rohith Kumar, Divya Sekhar Vaka, Y. S. Rao Centre of Studies in Resources Engineering, IIT Bombay, Powai-400076, Mumbai, India Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] KEYWORDS: Interferometry, subsidence, PALSAR, oil and gas wells ABSTRACT SAR Interferometry (InSAR) is a technique by which a wide area can be mapped for surface deformation. The conventional InSAR technique has limitations due to baseline restriction, atmospheric phase delay and temporal decorrelation. Persistent Scatterer Interferometry (PSI) technique is an advanced InSAR technique, and it mitigates the atmospheric phase delay effect and geometric decorrelation to a large extent by utilizing a stack of interferograms and gives time series deformation with high accuracy. Extraction of oil and natural gas from underground deposits leads to land subsidence. The East coast of Andhra Pradesh (AP) state in Krishna-Godavari basin is most likely to be affected by this phenomena because of extraction of oil and natural gas from its underground reservoirs for the last two decades. In this paper, an attempt is made to know how the urban cities in this region are affected due to land subsidence using PSI technique. For this, two coastal test areas are selected and ALOS-1 PALSAR datasets from 2007 to 2011 comprising of 11 and 13 scenes are processed using PSI technique. Although the area predominantly agriculture, small villages, towns and cities provide adequate Persistent Scatterers (PS). From the results, land deformation rates of different cities in test area are observed. -

State and Non-State Marine Fisheries Management: Legal Pluralism in East Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh, India

STATE AND NON-STATE MARINE FISHERIES MANAGEMENT: LEGAL PLURALISM IN EAST GODAVARI DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH, INDIA …. Sarah Southwold-Llewellyn Rural Development Sociology Department of Social Sciences Wageningen University Wageningen, The Netherlands [email protected] [email protected] Sarah Southwold-Llewellyn, 2010 Key words: marine fisheries, traditional fishing, mechanised fishing, management, legal pluralism, East Godavari District This 2010 report is a revision of an earlier working paper, Cooperation in the context of crisis: Public-private management of marine fisheries in East Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh, India. IDPAD Working Paper No. 4. IDPAD: New Delhi and IDPAD: The Hague, 2006 (www. IDPAD.org). The Project, Co-operation in a Context of Crisis: Public-Private Management of Marine Fisheries in South Asia, was part of the fifth phase of the Indo-Dutch Programme for Alternative Development (2003-2006). IDPAD India Secretariat: Indian Institute of Social Science Research (ICSSR), New Delhi IDPAD The Netherlands secretariat: Netherlands Foundation for the Advancement of Tropical Research (WOTRO), The Hague, The Netherlands 2 Acknowledgements My research in East Godavari District would not have been possible without the cooperation and help of many more than I can acknowledge here. The help of many Government officers is greatly appreciated. On the whole, I was impressed by their professionalism, commitment and concern. They gave me their valuable time; and most of them were extremely candid. Much that they told me was ‘off the record’. I have tried to protect their anonymity by normally not citing them by name in the report. There are far too many to individuals to mention them all. -

Annexure to Trade Notice No. 01/2017 (General No

Annexure to Trade Notice No. 01/2017 (General No. 1/2017) Dated. 21.06.2017 issued from F.No. V/39/16/2017-CC(VZ)Estt.P.F.I ANNEXURE - I Visakhapatnam Zone : Visakhapatnam Commissionerate and Kakinada Sub-Commissionerate No. of Sl.No. Commissionerate Name Jurisdiction Divisions Divisions This Commissionerate will have the jurisdiction over (i) Visakhapatnam North Visakhapatnam Srikakulam, Vizianagaram, (ii) Visakhapatnam Central 01 4 Commissionerate Visakhapatnam & East Godavari (iii) Visakhapatnam South Districts of Andhra Pradesh (iv) Vizianagaram Division State Kakinada Sub- This Sub-Commissionerate will (i) Kakinada Division Commissionerate have the jurisdiction over East 02 2 (ii) Rajamahendravaram (stationed at Rajamahendravaram) Godavari District of Andhra (Under Visakhapatnam Division Commissionerate) Pradesh State Page 1 of 13 Annexure to Trade Notice No. 01/2017 (General No. 1/2017) Dated. 21.06.2017 issued from F.No. V/39/16/2017-CC(VZ)Estt.P.F.I Sl. GST Division Name Jurisdiction No. of Ranges Ranges No. (i) Bheemunipatnam This Division will have jurisdiction over GVMC (Greater (ii) Madhurawada Visakhapatnam Municipal Corporation) ward Nos. 1 to 19 & (iii) Muvvalavanipalem Bheemunipatnam, Padmanabham & Anandapuram Mandals (iv) Maddilapalem Visakhapatnam (v) Akkayyapalem 01 of Visakhapatnam District. This Division will also have 10 North (vi) Seethammapeta residuary jurisdiction over any other area which is not (vii) Dwarakanagar mentioned or existing in any division under Visakhapatnam (viii) Srinagar District. (ix) Aseelmetta -

The National Waterway (Kakinada-Puducherry Stretch of Canals and the Kaluvelly Tank, Bhadrachalam- Rajahmundry Stretch of River

THE NATIONAL WATERWAY (KAKINADA-PUDUCHERRY STRETCH OF CANALS AND THE KALUVELLY TANK, BHADRACHALAM- RAJAHMUNDRY STRETCH OF RIVER GODAVARI AND WAZIRABAD-VIJAYAWADA STRETCH OF RIVER KRISHNA) ACT, 2008 ACT NO. 24 OF2008 [17th November, 2008.] An Act to provide for the declaration of the Kakinada-Puducherry stretch of canals comprising of Kakinada canal, Eluru canal, Commamur canal, Buckingham canal and the Kaluvelly tank, Bhadrachalam-Rajahmundry stretch of river Godavari and Wazirabad-Vijayawada stretch of river Krishna in the States of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu and the Union territory of Puducherry to be a national waterway and also to provide for the regulation and development of the said stretch of the rivers and the canals for the purposes of shipping and navigation on the said waterway and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto. BE it enacted by Parliament in the Fifty-ninth Year of the Republic of India as follows:— 1. Short title and commencement.—(1) This Act may be called the National Waterway (Kakinada- Puducherry stretch of Canals and Kaluvelly Tank, Bhadrachalam-Rajahmundry stretch of River Godavari and Wazirabad-Vijayawada stretch of River Krishna) Act, 2008. (2) It shall come into force on such date1 as the Central Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, appoint. 2. Declaration of certain stretches of rivers and canals as National Waterway.—The Kakinada-Puducherry stretch of canals comprising of Kakinada canal, Eluru canal, Commamur canal, Buckingham canal and the Kaluvelly tank, Bhadrachalam-Rajahmundry stretch of river Godavari and Wazirabad-Vijayawada stretch of river Krishna, the limits of which are specified in the Schedule, is hereby declared to be a National Waterway. -

Development of National Waterways-4 I) NW 4 Declared

Development of National Waterways-4 i) NW 4 declared in November, 2008 for a total length of 1078 km under following stretches: a) River Godavari (Bhadrachalam to Rajahmundry) = 171 km b) River Krishna (Wazirabad to Vijayawada) = 157 km c) Kakinada Canal (Kakinada to Rajahmundry) = 50 km d) Eluru Canal (Rajahmundry to Vijayawada) = 139 Km e) Commamur Canal (Vijayawada to Pedaganjam) = 113 km f) North Buckingham Canal (Pedaganjam to Chennai) = 316 km g) South Buckingham Canal (Chennai to Merkanam) = 110 km h) Kaluvelly Tank (Markanam to Puducherry) = 22 km Total =1078 km ii) NW-4 extended by NW Act-2016: • Revised length 2890KM a. River Krishna from Wazirabad to Galagali (628 Km) b. River Godavari from Bhadrachalam to Nasik (1184Km) iii) MoU signed with Govt. of Andhra Pradesh for development of NW-4 in Andhra Pradesh on 14th April’2016 proposed to be developed in the following phases. Phase-I: -Muktyala to Vijayawada (Krishna River) (82 Km) Phase-II: -Vijayawada to Kakinada (Eluru canal & Kakinada canal) and Rajahmundry to Polavaram stretch of Godavari (233 Km) Phase-III: -Commamur Canal, Buckingham canal and balance stretches of Krishna & Godavari Rivers (573km) iv) Development of Muktiyala to Vijayawada (Krishna River, 82 Km) stretch commenced under phase I. This will provide an efficient logistics solution to boost the economic growth of the region and facilitate the development of the capital city Amravati (during its early development stage) as substantial construction material is expected to be transported on this stretch of NW-4. The current status and targets for various projects on NW-4 as under. -

Quarantine Centre - Andhra Pradesh

QUARANTINE CENTRE - ANDHRA PRADESH Room rate(includi Contact Name of Number of ng meals Person(government Contact District: Type: Hotel/Quarantine Center: Rooms and taxes): Contact Number: offcial in-charge) Number: Remarks: VISAKHAPATNAM On Gratis Vikas Junior College Category Category 1:0 9052782060 Dr. Padma Priya 9052782060 1:74 VISAKHAPATNAM On Gratis Viajaya Residency Category Category 1:0 6300538289 Dr.Satyanarayana 6300538289 1:38 VISAKHAPATNAM On Payment The Park Hotel Category Category 9849121197 Anitha 9000782783 Single Occupancy for 14 1:20 1:35000 days VISAKHAPATNAM On Payment TAJ GATEWAY Category Category 7892142134 Anitha 9000782783 Single Occupancy for 14 1:40 1:35000 days VISAKHAPATNAM On Gratis Srikanth Lodge Category Category 1:0 9100064946 B.Ravikumar 9100064946 1:20 VISAKHAPATNAM On Gratis Sri Sai Brundavan grand Category Category 1:0 6300538289 Dr.Satyanarayana 6300538289 inn 1:28 VISAKHAPATNAM On Gratis SRI PALIMAR Category Category 1:0 9441207504 Dr.SUJATHA 9441207504 1:24 VISAKHAPATNAM On Gratis Post Metric Hostel G) Category 1:8 Category 1:0 9676376031 SDr.S.Vinnila 9676376031 VISAKHAPATNAM On Gratis NARAYANA IIT GIRLS Category Category 1:0 8985356024 Dr.Rajesh Naidu 8985356024 CAMPUS BLOCK 1) 1:140 VISAKHAPATNAM On Gratis Narayana IIT Category Category 1:0 8332954588 Dr.Amaleswari 8332954588 1:92 VISAKHAPATNAM On Gratis NARAYANA CAMPUS Category Category 1:0 9966994015 Dr.Dhanalakshmi 9966994015 1:93 VISAKHAPATNAM On Payment MEGHALAYA Category Category 8008200120 Anitha 9000782783 Single Occupancy for 14 1:45 -

The National Waterway (Kakinada-Puducherry Stretch of Canals and the Kaluvelly Tank, Bhadrachalam-Rajahmundry Stretch of River G

THE NATIONAL WATERWAY (KAKINADA-PUDUCHERRY STRETCH OF CANALS AND THE KALUVELLY TANK, BHADRACHALAM-RAJAHMUNDRY STRETCH OF RIVER GODAVARI AND WAZIRABAD-VIJAYAWADA STRETCH OF RIVER KRISHNA) ACT, 2008 # NO. 24 OF 2008 $ [17th November, 2008.] + An Act to provide for the declaration of the Kakinada-Puducherry stretch of canals comprising of Kakinada canal, Eluru canal, Commamur canal, Buckingham canal and the Kaluvelly tank, Bhadrachalam-Rajahmundry stretch of river Godavari and Wazirabad- Vijayawada stretch of river Krishna in the States of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu and the Union territory of Puducherry to be a national waterway and also to provide for the regulation and development of the said stretch of the rivers and the canals for the purposes of shipping and navigation on the said waterway and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto. BE it enacted by Parliament in the Fifty-ninth Year of the Republic of India as follows:- @ 1. % Short title and commencement. ! 1. Short title and commencement. – (1) This Act may be called the National Waterway (Kakinada-Puducherry stretch of Canals and Kaluvelly Tank, Bhadrachalam-Rajahmundry stretch of River Godavari and Wazirabad-Vijayawada stretch of River Krishna) Act, 2008. (2) It shall come into force on such date as the Central Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, appoint. @ 2. % Declaration of certain stretches of rivers and canals as National Waterway. ! 2. Declaration of certain stretches of rivers and canals as National Waterway. -The Kakinada-Puducherry stretch of canals comprising of Kakinada canal, Eluru canal, Commamur canal, Buckingham canal and the Kaluvelly tank, Bhadrachalam- Rajahmundry stretch of river Godavari and Wazirabad-Vijayawada stretch of river Krishna, the limits of which are specified in the Schedule, is hereby declared to be a National Waterway. -

RAIL DEVELOPMENTAL WORKS Visakhapatnam–Secunderabad AC (Weekly) 10

Green Initiatives 1. Revival of Water bodies is completed with the cost of `4.15 lakh. 2. LED lighting is completed at all stations with in Kakinada Parliamentary jurisdiction. Passenger Train Services Kakinada Details of New Trains/Additional Stoppage/Special Trains/Extension provided for Existing Parliamentary Constituency Trains in Kakinada Parliamentary Constituency Jurisdiction. Shri Narendra Modi New Trains Introduced 6. Kakinada to Secunderabad 79 special train Hon’ble Prime Minister 1. Tr.No.22841/22842 Santragachi – Chennai 7. Kakinada to Tirupati 38 special train Express 8. Kakinada to Velankini 1 special train Provision of Stoppage 9. Kakinada to Viajayawada 3 special trains 1. T r . N o . 1 2 7 8 4 / 1 2 7 8 3 S e c u n d e r a b a d ‐ RAIL DEVELOPMENTAL WORKS Visakhapatnam–Secunderabad AC (Weekly) 10. Kakinada to Guntur 2 special trains Express stoppage at Samalkota and Annavaram 11. Kakinada to Kacheguda 53 special trains Kakinada Parliamentary Constituency Jurisdiction 2. Tr.No.22708/22707 Tirupati–Visakhapatnam 12. Kakinada to Lingampalle 1 special train –Tirupati Double Decker Tri‐Weekly Express stoppage at Samalkota and Tuni 13. Kakinada to Renigunta 2 special trains 3. Tr . N o . 2 2 8 0 1 / 2 2 8 0 2 V i s a k h a p a t n a m – 14. Kakinada to Secunderabad 13 special trains Chennai–Visakhapatnam Express (Weekly) South Central Railway stoppage at Annavaram and Samalkot 15. Kakinada to Tirupati 55 special trains serving the entire state of 4. Tr.No.18112/18111 Yesvantpur –Tatanagar Express 16. Kotipalli to Tuni 6 special trains Telangana, major portion Weekly stoppage at Samalkot 17. -

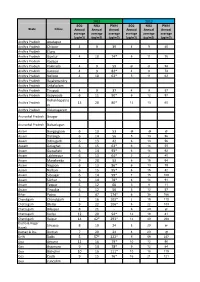

Combined Namp Data from 2011 to 2015

2011 2012 SO2 NO2 PM10 SO2 NO2 PM10 State Cities Annual Annual Annual Annual Annual Annual average average average average average average (µg/m3) (µg/m3) (µg/m3) (µg/m3) (µg/m3) (µg/m3) Andhra Pradesh Anatapur Andhra Pradesh Chitoor 4 9 39 4 9 40 Andhra Pradesh Eluru Andhra Pradesh Guntur 4 10 74* 5 11 75 Andhra Pradesh Kadapa Andhra Pradesh Kakinada 4 9 59 @ @ 58 Andhra Pradesh Kurnool 4 9 82* 4 9 74 Andhra Pradesh Nellore 4 10 63* 5 11 62 Andhra Pradesh Rajahmundry Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Andhra Pradesh Tirupati 4 9 37 4 9 37 Andhra Pradesh Vijaywada 6 11 90* 6 12 97 Vishakhapatna Andhra Pradesh 13 20 80* 12 13 65 m Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Arunachal Pradesh Itnagar Arunachal Pradesh Naharlagun Assam Bongaigaon 6 13 53 @ @ @ Assam Daranga 6 14 56 5 13 56 Assam Dibrugarh 6 13 42 6 13 56 Assam Golaghat 6 15 63* 6 14 55 Assam Guwahati 6 14 93* 6 14 92 Assam Lakhimpur 6 13 64* 2 2 45 Assam Margherita 9 20 53 6 15 54 Assam Nagaon 6 13 86* 6 13 79 Assam Nalbari 6 15 95* 6 15 82 Assam Sibsagar 6 14 99* 7 15 109 Assam Silchar 6 14 78* 6 14 91 Assam Tezpur 5 12 60 3 9 11 Assam Tinsukia 6 12 56 5 12 57 Bihar Patna 5 47 174* 6 36 166 Chandigarh Chandigarh 2 16 102* 2 19 110 Chattisgarh Bhillai 9 22 106* 8 22 103 Chattisgarh Bilaspur 8 21 - 6 20 @ Chattisgarh Korba 12 20 94* 12 19 81 Chattisgarh Raipur 14 42* 293* 14 40 268 Dadra & Nagar Silvassa 8 19 24 8 20 @ Haveli Daman & Diu Daman 7 20 24 8 20 @ Delhi Delhi 5 57* 222* 5 59 237 Goa Amona 11 16 79* 10 12 90 Goa Assanora 9 14 78* 9 12 84 Goa Bicholim 10 16 111* 10 18 119 Goa Codli 9 15 -

Office of the Chief Commissioner of Customs & Central

OFFICE OF THE CHIEF COMMISSIONER OF CUSTOMS & CENTRAL TAX VISAKHAPATNAM ZONE GST Bhavan, Port Area, Visakhapatnam- 530 035. Quarter ending Dec, 2019 A. Chief Commissioner Office/ Location of CPIO Appellate Authority Notified officer for Sl.No Jurisdiction GST Commissionerate (Sh./Smt.) (Sh./Smt.) payment of fees Shri. Aravinda Das, Shri. J.M.Kishore, Office of the Chief Assistant Commissioner Joint Commissioner In respect of all Drawing and Commissioner of Office of the Chief Commissioner of Office of the Chief Commissioner of matters Disbursing officer, Customs & Central Central Tax & Customs, Central Tax & Customs, pertaining to Central Tax, Tax, Visakhapatnam Visakhapatnam Zone, GST 1 Visakhapatnam Zone, GST Bhavan, Chief Visakhapatnam Zone, GST Bhavan, Bhavan, Port Area, Port Area, Commissioner's GST Port Area, Visakhapatnam- 530 035 Visakhapatnam- 530 035. office, Commissionerate, Visakhapatnam- 530 0891-285396 (Tel.) Tel. No.: 0891-2561450 Visakhapatnam. Visakhapatnam. 035 0891-2561942 (Fax) Fax No.: 0891-2561942 B. Commissioner Notified officer Sl. GST CPIO Appellate Authority Jurisdiction for payment of No. Commissionerate (Sh./Smt.) (Sh./Smt.) fees Shri. V. Prakash Babu, Shri S. Narasimha Reddy, In respect of all Assistant Commissioner of Central Tax, Addl. Commissioner of Central Tax, matters pertaining Visakhapatnam Visakhapatnam GST Commissionerate, Visakhapatnam Commissionerate, V. Prakash Babu, to Visakhapatnam 1 GST GST Bhavan, Port Area, Visakhapatnam- Central Excise Building, Port Area, Assistant GST Commissionerate 530 035 Visakhapatnam – 530 035. Commissioner Commissionerate Tel: 0891-2853180 Tel: 0891-2522794 (Hqrs.) Fax: 0891-2502451 Fax: 0891-2502451 Guntur G. Gobalakrishnan, Assistant M. Rama Mohana Rao, Additional In respect of all CAO, Hqrs Office, GST Commissioner Commissioner O/o the matters pertaining Central Tax, Commissionerate O/o the Commissioner of Central Tax, Commissioner of Central Tax, to Central Tax Guntur. -

Expression of Interest

EXPRESSION OF INTEREST ENGAGING CONSULTANT FOR DEBT SYNDICATION OF KAKINADA – SRIKAKULAM PIPELINE (PHASE-2) NOTICE INVITING EXPRESSION OF INTEREST (EOI) Ref. APGDC / KSPL (PHASE-2) / LOAN / 2019-20 Date: 16.03.2020 ENGAGEMENT OF CONSULTANT FOR DEBT SYNDICATION OF KAKINADA – SRIKAKULAM PIPELINE PROJECT (PHASE-2) (A) Introduction: Andhra Pradesh Gas Distribution Corporation Ltd. (APGDC), a 50:50 Joint Venture of Government of Andhra Pradesh (represented by Andhra Pradesh Gas Infrastructure Corporation Ltd. – APGIC, Andhra Pradesh Power Generation Corporation – APGENCO & Andhra Pradesh Industrial Infrastructure Corporation – APIIC) and GAIL Gas Ltd. (100% Subsidiary of GAIL (India) Ltd., a Central PSU), has been incorporated on 10th January 2011 with an objective of designing / developing Natural Gas supply / Distribution Network, Gas Processing through Liquefaction / Re-gasification Plants and to import, store, transport & distribute Natural Gas in the entire state of Andhra Pradesh. The initial authorized Share Capital of APGDC is Rs. 500 Crore. APGDC, in July 2014, was granted Authorization by PNGRB to lay, build, operate and expand Kakinada – Srikakulam Natural Gas Pipeline (KSPL). As per the terms of the Authorization, the Pipeline was to be commissioned within 36 months i.e. by July 2017. While conceptualizing KSPL, (proposed) Kakinada FSRU & Gangavaram LNG Terminal were considered the main gas sources. However, due to various techno-commercial issues including Gas pricing / firm commitments for Terminal capacity utilization, proposed FSRU & LNG Terminal projects have not come up, thereby constraining APGDC to identify a reliable alternative Gas Source for KSPL prior to commencing the Project execution activities. Accordingly, initial project take off was delayed and APGDC could not complete the Project by July 2017. -

COVID-19 Testing Labs

भारतीय आयु셍वज्ञि ान अनुसधं ान पररषद वा्य अनुसंधान 셍वभाग, वा्य और पररवार क쥍याण मंत्रालय, भारत सरकार Date: 24/05/2020 Total Operational (initiated independent testing) Laboratories reporting to ICMR: Government laboratories : 428 Private laboratories : 182 - Real-Time RT PCR for COVID-19 : 452 (Govt: 303 + Private: 149) - TrueNat Test for COVID-19 : 104 (Govt: 99 + Private: 05) - CBNAAT Test for COVID-19 : 54 (Govt: 26 + Private: 28) Total No. of Labs : 610 *CSIR/DBT/DST/DAE/ICAR/DRDO Laboratories. #Laboratories approved for both Real-Time RT-PCR and TrueNat/CBNAAT $Laboratories approved for both TrueNAT and CBNAAT S. Names of Test Names of Government Institutes Names of Private Institutes No. States Category 1. Andhra RT-PCR 1. Sri Venkateswara Institute of Medical Pradesh (52) Sciences, Tirupati 2. Sri Venkateswara Medical College, Tirupati 1 | P a g e S. Names of Test Names of Government Institutes Names of Private Institutes No. States Category 3. Rangaraya Medical College, Kakinada 4. #Sidhartha Medical College, Vijaywada 5. Govt. Medical College, Ananthpur 6. Guntur Medical College, Guntur 7. Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Kadapa 8. Andhra Medical College, Visakhapatnam 9. Govt. Kurnool Medical College, Kurnool 10. Govt. Medical College, Srikakulam TrueNat 11. Damien TB Research Centre, Nellore 12. SVRR Govt. General Hospital, Tirupati 13. Community Health Centre, Gadi Veedhi Saluru, Vizianagaram 14. Community Health Centre, Bhimavaram, West Godavari District 15. Community Health Centre, Patapatnam 16. Community Health Center, Nandyal, Banaganapalli, Kurnool 17. GSL Medical College & General Hospital, Rajahnagram, East Godavari District 18. District Hospital, Madnapalle, Chittoor District 19.