Amplifiers and Effects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magpick: an Augmented Guitar Pick for Nuanced Control

Magpick: an Augmented Guitar Pick for Nuanced Control Fabio Morreale Andrea Guidi Andrew McPherson Creative Arts and Industries Centre For Digital Music Centre For Digital Music University of Auckland, Queen Mary University of Queen Mary University of New Zealand London, UK London, UK [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper introduces the Magpick, an augmented pick for electric guitar that uses electromagnetic induction to sense the motion of the pick with respect to the permanent mag- nets in the guitar pickup. The Magpick provides the gui- tarist with nuanced control of the sound that coexists with traditional plucking-hand technique. The paper presents three ways that the signal from the pick can modulate the guitar sound, followed by a case study of its use in which 11 guitarists tested the Magpick for five days and composed a piece with it. Reflecting on their comments and experi- Figure 1: The Magpick is composed of two parts: a ences, we outline the innovative features of this technology hollow body (black) and a cap (brass). from the point of view of performance practice. In partic- ular, compared to other augmentations, the high tempo- ral resolution, low latency, and large dynamic range of the The challenge is to find ways to sense the movement of Magpick support a highly nuanced control over the sound. the pick with respect to the guitar with high resolution, Our discussion highlights the utility of having the locus of high dynamic range, and low latency, then use the resulting augmentation coincide with the locus of interaction. -

Dave Navarro - Beyond Addiction "Guitar World" (N°? - Février 1994) - Alan Di Perna

Dave Navarro - Beyond Addiction "Guitar World" (n°? - Février 1994) - Alan di Perna Clean and Sober Dave Navarro lives for today with the Red Hot Chili Peppers. L.A. is burning. A series of wickedly devastating brushfires have encircled the City of Angels, turning the surrounding hills into a raging inferno. But Dave Navarro looks implacably cool as he pilots his black Harley down Ventura Boulevard. The guitarist's newly sprouted goatee gives him a conquistador's air of stony self-possession as he glides along the wide thoroughfare. A bandanna and shades protect his hair and eyes from the pall of smoke and cinders that have made the city's air seem like the mouth of a badly vented fireplace. Angelenos have learned not to let castastrophe interrupt their daily lives, and Navarro is no exception. His bike safely stashed in a "Loading Only" zone, the guitarist enters a trendy coffeehouse--one of those self-consciously bohemian places that could only exist in L.A.'s San Fernando Valley. Settling onto a worn antique sofa, he orders a cup of black decaf and a bowl of cereal moistened with fruit juice. "I don't eat dairy," he explains. "No caffeine either. Right now, this is my only vice..." He smiles as he lights the first of many cigarettes. Studying the self-confident, purposeful guy seated at my side, I can't help but contrast him with the Dave Navarro I interviewed two years ago [GW, September '91]. At that time, he was a slavering, incoherent wreck, badly strung out on heroin and unable to even locate his shoes. -

THE BIRTH of HARD ROCK 1964-9 Charles Shaar Murray Hard Rock

THE BIRTH OF HARD ROCK 1964-9 Charles Shaar Murray Hard rock was born in spaces too small to contain it, birthed and midwifed by youths simultaneously exhilarated by the prospect of emergent new freedoms and frustrated by the slow pace of their development, and delivered with equipment which had never been designed for the tasks to which it was now applied. Hard rock was the sound of systems under stress, of energies raging against confnement and constriction, of forces which could not be contained, merely harnessed. It was defned only in retrospect, because at the time of its inception it did not even recognise itself. The musicians who played the frst ‘hard rock’ and the audiences who crowded into the small clubs and ballrooms of early 1960s Britain to hear them, thought they were playing something else entirely. In other words, hard rock was – like rock and roll itself – a historical accident. It began as an earnest attempt by British kids in the 1960s, most of whom were born in the 1940s and raised and acculturated in the 1950s, to play American music, drawing on blues, soul, R&B, jazz and frst-generation rock, but forced to reinvent both the music, and its world, in their own image, resulting in something entirely new. However, hard rock was neither an only child, nor born fully formed. It shared its playpen, and many of its toys, with siblings (some named at the time and others only in retrospect) like R&B, psychedelia, progressive rock, art-rock and folk-rock, and it emerged only gradually from the intoxicating stew of myriad infuences that formed the musical equivalent of primordial soup in the uniquely turbulent years of the second (technicolour!) half of the 1960s. -

Tommy Shaw, Styx

BACKSTAGE PASS Jimmy Johnson/Tommy shaw, sTyx JIMMY JOHNSON/ TOMMY SHAW, STYX Top Canadian guitar tech Jimmy Johnson gives Matt Frost a behind-the-scenes look at Tommy Shaw’s onstage rig immy Johnson secured his fi rst professional teching job back in 1974 when an Jold drumming high- school buddy successfully auditioned for an up-and-coming band on the eve of their fi rst ever US tour. Jimmy’s buddy was Neil Peart and the band, of course, was Rush, and for nearly 25 years Johnson worked pretty much full-time as Alex Lifeson’s guitar technician. Other artists to dutifully rely upon Jimmy’s teching prowess over the years have included Metallica, Todd Rundgren, Damn Yankees, Peter Frampton, Glass Tiger, Tesla, Tom Cochrane, Collective Soul and Th e Cars. Johnson fi rst hooked up with Styx in the late ’90s, after Rush announced they were taking a sabbatical, and he’s been Tommy Shaw’s personal guitar technician ever since. And on top of all of Jimmy’s on-the-road responsibilities with Styx, he also Jimmy with Tommy Shaw manages to fi nd the time to manage his own business, mates so we’re all looking forward Jimmy and Tommy are currently using the Vibramate install kit,” Gorgomyte, which manufactures to a good run. Touring as much as taking out a total of 14 electrics enthuses Johnson. “I recommend one of the industry’s most we do and also running my and acoustics in the USA, although people go to www.vibramate.com respected fret and fi ngerboard Gorgomyte business pretty much as Johnson explains, “We’re to learn more about what really is cleaning products (also called keeps me running at full tilt, which constantly evolving and trying an amazing innovation.” Gorgomyte). -

THE WORLD's FIRST PLAY-IN DEVICE the Tonerite

1 THE WORLD'S FIRST AND PREMIER AUTOMATIC PLAY-IN DEVICE Now Available for String Instruments and Drums! Acoustic, Electric, and Bass Guitar Mandolin, Violin, Viola, Cello, Double Bass & Ukulele Percussion Instrument: Drum The ToneRite PRODUCT AND PROCESS WORKS IN TWO SIMPLE STEPS First, to unlock the maximum potential of your instrument… The play-in de-dampening process is a well-known phenomenon that occurs when wood instruments are played regularly for many years. Through on-going research, ToneRite has developed automatic play-in technology that can rapidly and safely take your instrument to its highest potential in less than a week. The ToneRite is nearly silent, lasts a lifetime, and will improve your instruments tone, volume and playability whenever you are not playing it yourself. Second, to keep your instrument at its best… The ToneRite is also great for keeping your instrument in top playing shape. As instruments go un-played they begin to build up a natural tension which results in the gradual loss of tonal quality. Continual use of the ToneRite allows your instrument to be ready for you whenever you have the inspiration to play. Your instrument is at its best, all the time. 2 THE SECRET BEHIND THE TONERITE IS its ability to (continually) produce and efficiently transfer vibrational energy into an instrument, safely recreating and magnifying the physics that occur naturally while playing. This stimulation produces a change to the integrated components within an instrument and increases their ability to resonate together as a whole. The result is added volume and instruments that are easier to play with a sound that is more full and balanced. -

Encore El & AC Bro 10 Layout 1

he most important guitar you’ll ever buy is your We know that a great instrument inspires, and you T first one… deserve the best! A great ‘first guitar’ means you’ll want to play for Whether you play for personal enjoyment - knowing the rest of your life! that you’re learning to play one of the most exciting of musical instruments, or for relaxation, or recreation, We took the decision to make the Encore Blaster or are fired up with the inspiration to get a band Series™ outshine, and outperform any electric and together, get some gigs in pubs and clubs… whatever; bass guitar in the world, anywhere near the price! everyone famous started just the same way! Why? Write and record some songs by yourself or with your friends – post ‘em on a music networking site, get people liking what you do… recognition and the big time beckons! ® BLASTER Elec 1 Whatever you do, just have fun and enjoy your playing. Encore Blaster Series guitars feature specially created So what’s so special about the Encore Blaster Series? vintage-voiced pickups to produce astonishingly Simple really, for over 30 years Encore has been the accurate and authentic tone. #1 ‘first guitar.’ Hardware too is fundamental to tone and performance. We invited British Guitar Guru, Trev Wilkinson, the The Encore Blaster Series features custom-designed renowned designer behind Fret-King® Italia®, and hardware and vibrato bridges which significantly Vintage® guitars, and the creator of many now- enhance the superb tone and playability of these standard guitar innovations, to design in to the guitars. -

Gear Acquisition Syndrome

Jan-Peter Herbst & Jonas Menze Gear Acquisition Syndrome, also known as GAS, is commonly Syndrome Gear Acquistion understood as the musicians’ unrelenting urge to buy and own Gear Acquistion Syndrome instruments and equipment as an anticipated catalyst of creative energy and bringer of happiness. For many musicians, it involves the unavoidable compulsion to spend money one does not have on Consumption of Instruments and gear perhaps not even needed. The urge is directed by the belief that Technology in Popular Music acquiring another instrument will make one a better player. This book pioneers research into the complex phenomenon named GAS from a variety of disciplines, including popular music studies and music technology, cultural and leisure studies, consumption research, sociology, psychology and psychiatry. The newly created theoretical framework and empirical studies of online communities and offline music stores allow the study to consider musical, social and personal motives, which influence the way musicians think about and deal with equipment. As is shown, GAS encompasses a variety of practices and psychological processes. In an often life-long endeavour, upgrading the rig is accompanied by musical learning processes in popular music. Jan-Peter Herbst & Jonas Menze Jan-Peter 10.5920/GearAcquisition.fulltext Jan-Peter Herbst & Jonas Menze Gear Acquisition Syndrome Consumption of Instruments and Technology in Popular Music 10.5920/GearAcquisition.fulltext Published by University of Huddersfield Press University of Huddersfield Press The University of Huddersfield Queensgate Huddersfield HD1 3DH Email enquiries [email protected] First published 2021 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. -

From Load in to Load out How to Play a Live Show

MusicNSW’s Industry Essentials From Load In to Load Out How to play a live show So, you’ve been asked to play your first show! Here are some things you might need to prepare and be aware of. Before the show: + Rehearse! – Rehearsals are important for all performing artists to combat nerves and give yourself the best chance for a good first impression. You can record your rehearsals to check how you’re sounding. + Check your performance agreement – How much is the performance fee? Are there any terms or obligations that are a part of your performance? Get it in writing if possible. + Promote the event – By bringing as many people as possible to a show, you’ll give the event organiser, headline band or venue more reason to book you again next time. + Backline – You’ll need to let the venue or event organiser know your backline requirements for your performance. This is any equipment you won’t bring along to the venue, such as a drum kit, DI and amplifiers. Each venue has a list of equipment available so make sure they have what you need. + Stage plot – For a bigger performance such as a festival, you may be required to provide a stage plot for your band. The stage plot is essentially a diagram indicating how your band likes to be setup on stage – including where each member stands, what instrument and inputs are required. For example, a bass player may have an amp setup (stage right) but also require a d/I (direct input). These types of requirement should be drawn using a simple diagram and explained clearly. -

Alex's Guitar Tech

•• _ ...... .- 4I_~ ----'---------___ -...."'--- __.4-......-...--.._ ............. .....r--~-- ISSUE No.44 - AUTUMN/FALL 1998 ~._4IL~ _ •• _ .... __ It " .I -----------~--------~--~-..~--------~~.pl.--t---~----~----~- to, Hello and welcome to the latest 'Spirit Of Gold Award. A complete set of Rush' . Without doubt the highlight of this re- mastered CDs, various T.shirts issue is our exclusive interview with Jimmy some black and white promo photos Johnson, (see opposite). It was a real pleasure and some promo CDs. Worth coming talking to a very open and generous man (thanks just for a chance of winning one must go to Russ Ryan for introducing us) cheers of those. We are lining up a big mate! We promised you three exclusive interviews surprise (if it works out) as well last issue; however the promised Larry Gowan and nudge nudge wink wink! There will Kevin Shirley interviews were squeezed out by also be a Rock Disco and another the length of the Jimmy Johnson one, they will live band playing provided by the of course appear in the next issue No: 45 which university themselves. This will will be with you in November. help keep our costs down re-bar staff and security etc. Hope to The response to the readers poll which we sent see you all on the 19th of the 9th. out with the last issue has been less than enthusiastic, hence we will not be bringing you Details of the forthcoming live the result of it at the convention as we stated album continue to emerge (all un last issue. Instead you will find the poll once confirmed) The title is 'Different again enclosed with this issue, so please take Stages' one CD will feature a the time to fill it out and mail it to us at show from the 'Kings' tour London the address on the right. -

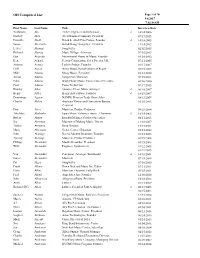

OH Completed List

OH Completed List Page 1 of 70 9/6/2017 7:02:48AM First Name Last Name Title Interview Date Yoshiharu Abe TEAC, Engineer and Innovator d 10/14/2006 Norbert Abel Abel Hammer Company, President 07/17/2015 David L. Abell David L. Abell Fine Pianos, Founder d 10/18/2005 Susan Aberbach Hill & Range Songs Inc., President 11/14/2012 Lester Abrams Songwriter 02/02/2015 Richard Abreau Music Village, Advocate 07/03/2013 Gus Acevedo International House of Music, Founder 01/20/2012 Ken Achard Peavey Corporation, Sales Director UK 07/11/2005 Antonio Acosta Luthier Strings, Founder 01/17/2007 Cliff Acred Amro Music, Band Instrument Repair 07/15/2013 Mike Adams Moog Music, President 01/13/2010 Arthur Adams Songwriter, Musician 09/25/2011 Edna Adams World Wide Music, Former Sales Executive 04/16/2010 Paul Adams Piano Technician 07/17/2015 Hawley Ades Shawnee Press, Music Arranger d 06/10/2007 Henry Adler Henry Adler Music, Founder d 10/19/2007 Dominique Agnew NAMM, Director Trade Show Sales 08/13/2009 Charles Ahlers Anaheim Visitor and Convention Bureau, 01/25/2013 President Don Airey Musician, Product Endorser 09/29/2014 Takehiko Akaboshi Japan Music Volunteer Assoc., Chairman d 10/14/2006 Bulent Akbay Istanbul Mehmet, Product Specialist 04/11/2013 Joy Akerman Museum of Making Music, Docent 11/30/2007 Toshio Akiyama Band Director 12/15/2011 Marty Albertson Guitar Center, Chairman 01/21/2012 John Aldridge Not So Modern Drummer, Founder 01/23/2005 Tommy Aldridge Musician, Product Endorser 01/19/2008 Philipp Alexander Musik Alexander, President 03/15/2008 Will Alexander Engineer, Synthesizers 01/22/2005 01/22/2015 Van Alexander Composer, Arranger, Bandleader d 10/18/2001 James Alexander Musician 07/15/2015 Pat Alger Songwriter 07/10/2015 Frank Alkyer Down Beat and Music Inc, Editor 03/31/2011 Davie Allan Musician, Guitarist, Early Rock 09/25/2011 Fred Allard Amp Sales, Inc, Founder 12/08/2010 John Allegrezza Allegrezza Piano, President 10/10/2012 Andy Allen Luthier 07/11/2017 Richard (RC) Allen Luthier, Friend of Paul A. -

TECHNICAL PRODUCTION RIDER 2017 V2

TECHNICAL PRODUCTION RIDER 2017 v2 This rider is updated regularly and pursuant to Production Manager’s advance. Please check that you have the latest version, and disregard any previously released versions or “word of mouth” information, other than information sent only by those authorized by Nile Rodgers Productions. Any possible options and alternative for the following equipment, other than what is listed herein, must meet Chic Production Manager’s approval. Pages included on this document: 1. Cover, contents and presentation 2. P.A system and FOH requirements 3. Monitor requirements 4. Microphones/D.I.boxes and accessories 5. Backline and band requirements 6. Miscellaneous consumables, risers, required personnel 7. Input and Channel list 8. Stage plot 9. Lighting Design & requirements 10. Lighting plot 1 (truss fixtures) 11. Lighting plot 2 (floor fixtures) 12. Visuals Requirements (where applicable) John Ryan – Tech Production Manager/FOH Engineer - Nile Rodgers & Chic Production - [email protected] International cell: +39 3469487082 - - Italy cell: +39 3289173405 TECHNICAL PRODUCTION RIDER 2017 v2 page 2/12 Upon request, Chic Production may recommend our preferred audio/lighting rental company. P.A. System Requirements P.A. System: Professional quality, preferably flown, stereo four-way speaker system (three way + sub- woofers), capable of delivering 110 db distortion-free, wide band audio, evenly distributed throughout the venue, plus full range front fills and delay systems where needed. Software/hardware control for the -

USER GUIDE fi Cations and Cations Appearance Are Subjecttochange Withoutnotice

True to the Music JX62™ GUITAR AND AMP A/B SWITCHER USER GUIDE Radial Engineering Ltd. 1588 Kebet Way, Port Coquitlam BC V3C 5M5 tel: 604-942-1001 • fax: 604-942-1010 email: [email protected] • web: www.radialeng.com www.radialeng.com www.radialeng.com Copyright © 2014 Radial Engineering Ltd. All rights reserved • Specifi cations and appearance are subject to change without notice. Radial JX62 6x2 Guitar and Amp Switcher User Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Overview........................................................................................................................................1 Feature Set Overview ....................................................................................................................2 Getting Started .............................................................................................................................4 Making Connections ......................................................................................................................4 Adding More Guitars......................................................................................................................5 Adding A Second Amp ...................................................................................................................5 Using The Channel Thru Outputs ..................................................................................................6 Drag Control ..................................................................................................................................6