Jan Woudstra: the Eco-Cathedral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nieuwsblad Van Friesland : Hepkema's Courant

Vrijdagavond 2 Januari 1942. - No. 1. HEPKEMA'S COURANT (69e jaargang) - HEERENVEE.N. Verschijnt Maandags-, Woensdags- en Vrijdagsavonds jtDVBRTENTIES P. reg. Ma. en Wo. 14 c. Vr. 16 c.; buiten 4 Noord. prov. Ma. en Wo. 18 c, Vr. 21 c. Reclamekolonnmen dubbele NIEUWSBALD VAN FRIESLAND pr. (0m2.-bel. inbegr.) LEESGBLD p. halfj. f2.60, Inning 16 et. Amerika p. J. £12.50. Losse nos. S et. Giro 5894. Tel. 2213. (Ken- getal K 5280). HOOFDRED.: W. Hielkema, Leeuwarden. J. Bruinsma, Heerenv. (pl.v.) van dezen oorlog voor Engeland onvoorwaar- zijn. De beslissende productiegebieden van vleescheoorlen, die niet in de nieuwe vleescb- EERSTE BLAD delijk noodzakelijke vloot en tenslotte voor grondstoffen in Zuid-Oost-Azië zullen echter prijzenbeschikking worden genoemd, niet meer mogen worde] ocflt. bladzijden; de even noodzakelijke bewapeningsindustrie volgens den loop der dingen binnen afzien- Dit no. bestaat uit ACHT de noodige manschappen en menschen op baren tijd niet meer den tegenstanders ten Ten overvloede wordt i la op ge- gewicht 55 gram. den duur tér beschikking te stellen. De ge- goede komen, maar in toenemende mate de wezen, dat het prijsaandnidingßbesduit voor per TOEKOMST beginnen echter, de spil de slagerswinkels onverminderd van kracht 50 FIJRER hulptroepen economische basis partners DE DE kleurde naar der van POSTTARIEF: porto binnenland DOOR uit laatste berichten ontleend kan wor- versterken. blijft. gtam \Yi cent; buitenland per 50 gr. 2% et. de den en zooals bij oorlogshandelingen van oorlog met bijzondere omstandig- Deze zijn BELANGSTELLING VOOR DES RIJKSCOMMISSARIS-RIJKSMINISTER dezen duur en hardheid niet anders te ver- heden, door de uitgestrekte gebieden, waar- RUIME wachten was, te versagen en zich te koeren in hij gevoerd wordt en vooral tegen de ons ARBEIDSDIENST. -

Nieuwsblad Van Friesland : Hepkema's Courant

Vrijdagavond 23 Mei 1941. - No. 61. HEPKEMA'S COURANT (68e Jaargang) HEERENVEEN. Verschijnt Maandags-, Woensdags- en Vrijdagsavonds p. peg. - ADVERTENTIES Maand, en Woened. no. 14 c, Vrljd.no. 16 o.j bulten 4 Noordel. prov. Maand, en Woenad. 18 0., Vrljd. 21 o. Reolamekolommen dubbele prijzen (Omzet- belasting inbegrepen). L.EESGELD per halfjaar f 2,63. Inning 16 et. Amerika p. jaar f 12.50. Losee no.'a. 5 et, Postrek. 5894. Tel. 2213 (Kengetal K 6280). NIEUWSBLAD VAN FRIESLAND EERSTE BLAD het gemeentebestuur bied ik u van harte deren per bakfiets naar het pakhuisje van Modevakschool A. Mulder-de Vries Het mim gelukwenschen aan. M. aan het Noordvliet te transporteeren, en veertig-jarig jubileum van „Zevenwouden” Wij nog steeds over, dat tegen wien de Officier wegens heling vier Hoofdredacteuren: Tjepkemastraat 18 Heerenveen verheugen ons er In een eenvoudidige bijeenkomst herdacht. de zetel van Zevenwouden destijds van Gor- maanden gevorderd had, werd veroordeeld W. HIELKEMA J. BRUINSMA redijk hier is overgegaan. tot deze straf. Op 3 Juni a.s. beginnen de nieuwe HEERENVEEN. Woensdag j.l. heeft de naar Leeuwarden Heerenveen Uit de getallen, welke hier hedenmorgen Diefstal en heling van levensmiddelen. Onderlinge Verzekeringsmij. „Zevenwouden" zijn genoemd, is wel gebleken, dat s?dert ■^^ Knip- en Naailessen te Heerenveen den dag herdacht, waarop De rechtbank veroordeelde voorts den 26- veertig jaar dien uw vereeniging in beduidende mate is Dit no. bestaat uit ACHT bladzijden; tot Coupeuse voor deze verzekeringmaatsohap- -jarigen monteur Jouwert K., te Leeuwarden Opleiding enz. enz. pij vooruitgegaan. Deze cijfers spreken boek- gewicht 55 werd opgericht. Dit feit ie in een een- deelen geven duidelijk beeld van en den 27-jarigen arbeider Ernestus van der gram. -

Dorpskrant 13.1 Nov. 2017

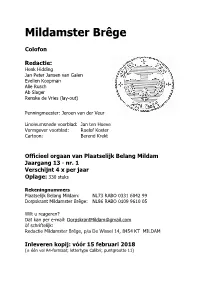

Mildamster Brêge Colofon Redactie: Henk Hidding Jan Peter Jansen van Galen Evelien Koopman Alie Rusch Ab Slager Renske de Vries (lay-out) Penningmeester: Jeroen van der Veur Linoleumsnede voorblad: Jan ten Hoeve Vormgever voorblad: Roelof Koster Cartoon: Berend Krekt Officieel orgaan van Plaatselijk Belang Mildam Jaargang 13 - nr. 1 Verschijnt 4 x per jaar Oplage: 330 stuks Rekeningnummers Plaatselijk Belang Mildam: NL73 RABO 0331 6042 99 Dorpskrant Mildamster Brêge: NL86 RABO 0109 9610 05 Wilt u reageren? Dat kan per e-mail: [email protected] òf schriftelijk: Redactie Mildamster Brêge, p/a De Wissel 14, 8454 KT MILDAM Inleveren kopij: vóór 15 februari 2018 (± één vel A4-formaat; lettertype Calibri; puntgrootte 11) INHOUDSOPGAVE Colofon ............................................................................................ 1 Contactpersoon Plaatselijk Belang ...................................................... 3 Buurtcoördinatoren ........................................................................... 3 Van het bestuur van Mildam .............................................................. 3 Evert Nijenhuis ................................................................................. 5 Thematische Brêge ........................................................................... 6 ONMKB 50 jaar ................................................................................. 6 Tjeerd Mevius ................................................................................... 8 Janny Jongedijk ............................................................................. -

Toelichting Op De Werkkaart Groene Diensten Oranjewoud-Katlijk

Werkkaart en toelichting Landschapsfonds Oranjewoud– Katlijk Juli 2010 TOELICHTING OP DE WERKKAART GROENE DIENSTEN ORANJEWOUD-KATLIJK De Werkkaart Groene Diensten is leidend voor de ruimtelijke keuze van de inzet van groene diensten in Oranjewoud-Katlijk. Welke diensten worden waar gevraagd? En met welk doel? Voor de werkkaart is geen nieuw beleid ontwikkeld. Bestaand beleid is geconcretiseerd en vertaald naar het werkgebied Oranjewoud-Katlijk. De toelichting op de werkkaart zoals hier voorligt geeft inzicht in gemaakte keuzes, de doelstellingen van de stichting en uiteindelijk waar welke groene diensten ingezet gaan worden voor het beheer en onderhoud van het landschap van Oranjewoud-Katlijk. Aanbieders, particuliere grondeigenaren zowel agrariërs als niet agrariërs kunnen op basis van de werkkaart op vrijwillige basis besluiten om groene diensten te gaan leveren. De groene diensten zelf –de instapeisen, het gewenste beheer en de hoog- te van de vergoedingen- zijn uitgewerkt in de Dienstenbundel Oranjewoud Katlijk . Beide documenten, de dienstenbundel en de werkkaart zijn onderdeel van het businessplan Land- schapsfonds Oranjewoud-Katlijk. Juni 2010 Werkkaart Groene Diensten Oranjewoud-Katlijk 3 4 INHOUDSOPGAVE 1 HUIDIGE SITUATIE EN BESTAAND BELEID 7 1.1 Huidige situatie en landschapstypen 7 1.2 Beleidsdoelen vanuit bestaand beleid 10 1.3 Wensbeelden per landschapstype 10 1.3.1 Wensbeeld en groene diensten in de woudontginningen 10 1.3.2 Wensbeeld voor en groene diensten in het landgoederenlandschap 12 1.3.3 Wensbeeld voor en groene diensten in de veenpolders 12 1.3.4 Wensbeeld voor en groene diensten in het beekdal 13 1.4 Groene diensten in Oranjewoud-Katlijk 14 2 OVERZICHT VAN DE VRAAG NAAR GROENE DIENSTEN 15 2.1 Doelstelling groene diensten Oranjewoud-Katlijk 15 2.2 Werkkaart groene diensten Oranjewoud-Katlijk 17 BIJLAGE: OVERZICHTSKAART LANDSCHAPSFONDS ORANJEWOUD KATLIJK Werkkaart Groene Diensten Oranjewoud-Katlijk 5 6 1. -

Ontgonnen Verleden

Ontgonnen Verleden Regiobeschrijvingen provincie Friesland Adriaan Haartsen Directie Kennis, juni 2009 © 2009 Directie Kennis, Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuur en Voedselkwaliteit Rapport DK nr. 2009/dk116-B Ede, 2009 Teksten mogen alleen worden overgenomen met bronvermelding. Deze uitgave kan schriftelijk of per e-mail worden besteld bij de directie Kennis onder vermelding van code 2009/dk116-B en het aantal exemplaren. Oplage 50 exemplaren Auteur Bureau Lantschap Samenstelling Eduard van Beusekom, Bart Looise, Annette Gravendeel, Janny Beumer Ontwerp omslag Cor Kruft Druk Ministerie van LNV, directie IFZ/Bedrijfsuitgeverij Productie Directie Kennis Bedrijfsvoering/Publicatiezaken Bezoekadres : Horapark, Bennekomseweg 41 Postadres : Postbus 482, 6710 BL Ede Telefoon : 0318 822500 Fax : 0318 822550 E-mail : [email protected] Voorwoord In de deelrapporten van de studie Ontgonnen Verleden dwaalt u door de historisch- geografische catacomben van de twaalf provincies in Nederland. Dat klinkt duister en kil en riekt naar spinnenwebben en vochtig beschimmelde hoekjes. Maar dat pakt anders uit. Deze uitgave, samengesteld uit twaalf delen, biedt de meer dan gemiddeld geïnteresseerde, verhelderende kaartjes, duidelijke teksten en foto’s van de historisch- geografische regio’s van Nederland. Zo geeft het een compleet beeld van Nederland anno toen, nu en de tijd die daar tussen zit. De hoofdstukken over de deelgebieden/regio’s schetsen in het kort een karakteristiek per gebied. De cultuurhistorische blikvangers worden gepresenteerd. Voor de fijnproevers volgt hierna een nadere uiteenzetting. De ontwikkeling van het landschap, de bodem en het reliëf, en de bewoningsgeschiedenis worden in beeld gebracht. Het gaat over de ligging van dorpen en steden, de verkavelingsvormen in het agrarisch land, de loop van wegen, kanalen en spoorlijnen, dijkenpatronen, waterlopen, defensielinies met fortificaties. -

Pipegaelloop 2015

Nummer naam Woonplaats Afstand Tijd 166 Hinde Fokkema Nijeberkoop 5 km 00:21:18 168 Wietske Beenen Gorredijk 5 km 00:22:16 196 Johan Greydanus Wijnjewoude 5 km 00:22:48 193 Marrit Bron Jubbega 5 km 00:23:12 171 Jesse Nieuwland Gorredijk 5 km 00:23:29 181 Rinske de Jong Jubbega 5 km 00:23:40 191 Elly Koning Enschede 5 km 00:24:04 198 Bouwe van der Meer Jubbega 5 km 00:24:43 175 Tineke van der Meer Heerenveen 5 km 00:24:56 97 Folkert Jongsma Gorredijk 5 km 00:25:00 192 Sandra Middel Jubbega 5 km 00:25:01 173 Britt Kleefstra Jubbega 5 km 00:25:46 169 Marcel Bomas Leeuwarden 5 km 00:25:50 176 Roel Straatman Gorredijk 5 km 00:26:18 179 Martijn de Haan Jubbega 5 km 00:26:35 183 Paula Rijkers Jubbega 5 km 00:26:37 180 Arend de Haan Jubbega 5 km 00:26:44 184 Jappie Sikkema Oudehorne 5 km 00:27:10 182 Adri Sluis Mildam 5 km 00:27:27 174 Wietske Blaauw Jubbega 5 km 00:28:33 172 Jelle Koopmans Jubbega 5 km 00:28:39 188 Erwin de Vries Hoornsterzwaag 5 km 00:28:55 99 Taco Dijk Hoornsterzwaag 5 km 00:29:53 98 Anne Dijk Hoornsterzwaag 5 km 00:30:05 178 Marjan Bakker Jubbega 5 km 00:30:19 199 Marjolein van der Meer Jubbega 5 km 00:31:12 187 Anny Feddema Katlijk 5 km 00:31:29 158 Gerrit Duits Sneek 5 km 00:31:32 185 Lisette Koopmans Hoornsterzwaag 5 km 00:31:39 96 Ellie Jongsma Nieuwehorne 5 km 00:32:01 157 Thijs Hofstra Wytgaard 5 km 00:33:45 195 Inge Jongsma Tijnje 5 km 00:34:35 194 Anja Jongsma Oudehorne 5 km 00:34:40 155 Herman Hoekstra Goutum 5 km 00:34:50 165 Sietse Jonker Jubbega 5 km 00:35:29 162 Fetsje Jonker Jubbega 5 km 00:35:30 186 Jan Dijk -

Dorpskrant 14.2 Juni 2019

Mildamster Brêge Colofon Redactie: Henk Hidding Jan Peter Jansen van Galen Evelien Koopman Alie Rusch Ab Slager Renske de Vries (lay-out) Penningmeester: Jeroen van der Veur Linoleumsnede voorblad: Jan ten Hoeve Vormgever voorblad: Roelof Koster Officieel orgaan van Plaatselijk Belang Mildam Jaargang 14 - nr. 2 Verschijnt 4 x per jaar Oplage: 330 stuks Rekeningnummers Plaatselijk Belang Mildam: NL73 RABO 0331 6042 99 Dorpskrant Mildamster Brêge: NL86 RABO 0109 9610 05 Wilt u reageren? Dat kan per e-mail: [email protected] òf schriftelijk: Redactie Mildamster Brêge, p/a De Wissel 14, 8454 KT MILDAM Inleveren kopij: vóór 15 september 2019 (± één vel A4-formaat; lettertype Calibri; puntgrootte 11) INHOUDSOPGAVE Colofon ............................................................................................ 1 Contactpersoon Plaatselijk Belang ...................................................... 3 Buurtcoördinatoren ........................................................................... 3 Van het bestuur van PB Mildam ......................................................... 3 Thema Brêge 14.3 ............................................................................ 4 Even voorstellen… ............................................................................. 5 Efkes foarstelle ................................................................................. 6 De resultaten van de energie-enquête ................................................ 7 Nogmaals de zwemplek .................................................................... -

Bucket List Check Ze Alle 10!

De Heerenveen ‘n gouden regio Bucket list Check ze alle 10! ACTIEF Loop met je blote voeten door het water bij het recreatiegebied De Heide. ddddd ACTIEF CULTUUR Leer de geschiedenis over de monumentale gebouwen in Heerenveen door de QR code op het gebouw te scannen. NATUUR ACTIEF CULTUUR Beklim de heuvel en adem de sferen rondom het Woutersbergje. CULTUUR Bezoek de zes enorme, monumentale beelden van Tony Gragg. (van 24 april tot 26 september) CULTUUR Bewonder het kunstwerk onder de brug bij Aldeboarn. NATUUR ACTIEF CULTUUR Sta bovenop de Kiekenberg dit is het hoogste punt in de omgeving van Nieuwehorne. NATUUR ACTIEF Beklim de 108 treden van de uitkijktoren Belvedère en kijk of je de Waddeneilanden TREINSPOOR kunt zien. AENGWIRDEN NES ACTIEF CULTUUR Wandel de kunstroute in Akkrum en ALDEBOARN bewonder de kunstwerken van de AKKRUM TURFROUTE ZWEMBAD plaatselijke (amateur) kunstenaars. JUBBEGA GERSLOOTPOLDER NATUUR ACTIEF CULTUUR Bezoek het Ecokathedraal in Mildam en GERSLOOT TERBAND verwonder je over de langdurige processenHOORNSTERZWAAG TJALLEBERD JUBBEGA HASKERDIJKEN tussen mens en natuur. LUINJEBERD NATUUR ACTIEF CULTUUR DE KNIPE Breng een ode aan de Wolf in Katlijk. HEERENVEEN OUDEHORNE BONTEBOK TURFROUTE ORANJEWOUD NIEUWEHORNE KATLIJK MILDAM OUDESCHOOT Kijk voor de adressen NIEUWESCHOOT op a cht e rzi jd e! ngoudenplak.nl De Heerenveen ‘n gouden regio Bucket list Recreatiegebied De Heide De Dreef Heerenveen Monumenten met QR code Scan de QR code voor meer informatie Woutersbergje Midden in de bossen, Oranjewoud Museum Belvedère – Tony Gragg beelden Oranje Nassaulaan 12, Heerenveen Brug Aldeboarn Súdkant, Aldeboarn Kiekenberg Siebe Annesweg, Oudehorne Uitkijktoren Belvedère Bieruma Oostingweg, Oranjewoud Kunstroute Station Galemaleane 1, Akkrum Ecokathedraal Mildam Yntzelaan, Mildam Stonehenge Schoterlandseweg 26, Katlijk MEER LEUKE DOEN&ZIEN UITJES VIND JE OP: WWW.NGOUDENPLAK.NL Of scan de QR code ngoudenplak.nl. -

Dorpskrant 14.4 Dec. 2019

Mildamster Brêge Colofon Redactie: Henk Hidding Jan Peter Jansen van Galen Evelien Koopman Alie Rusch Ab Slager Renske de Vries (lay-out) Penningmeester: Jeroen van der Veur Linoleumsnede voorblad: Jan ten Hoeve Vormgever voorblad: Roelof Koster Officieel orgaan van Plaatselijk Belang Mildam Jaargang 14 - nr. 4 Verschijnt 4 x per jaar Oplage: 325 stuks Rekeningnummers Plaatselijk Belang Mildam: NL73 RABO 0331 6042 99 Dorpskrant Mildamster Brêge: NL86 RABO 0109 9610 05 Wilt u reageren? Dat kan per e-mail: [email protected] òf schriftelijk: Redactie Mildamster Brêge, p/a De Wissel 14, 8454 KT MILDAM Inleveren kopij: vóór 15 februari 2020 (± één vel A4-formaat; lettertype Calibri; puntgrootte 11) INHOUDSOPGAVE Colofon ............................................................................................ 1 Contactpersoon Plaatselijk Belang ...................................................... 3 Buurtcoördinatoren ........................................................................... 3 Van het bestuur van PB Mildam ......................................................... 3 Herinrichting van Mildam-Noord ......................................................... 5 Subsidie Rabobank ............................................................................ 6 Piipskoft in het teken van de dag van de Mantelzorg ........................... 6 Thema Brêge 15.1 ............................................................................ 7 Lente .............................................................................................. -

Haskerland in De Loop Der Tijden

De schoolmeesters van Haskerland in de loop der tijden. 1. Joure.a 1a. De Latijnse school. Reeds in okt. 1593 is er sprake van de rector te Joure, die een toelage ontving van de Staten van Friesland;b zijn naam wordt evenwel niet vermeld. Maar te Franeker wordt in 1599 S. Scotus te Joure tot rector beroepen, die evenwel verklaart, dat hij niet kan komen.c We mogen dus aannemen, dat hij hier rector was van de Latijnse school. In 1598 was Scholtetus Regneri, "Recktoer op de Jouwer"; hij kocht toen een stuk land in Oldeholtwolde.d Ook op 11 nov. 1601 komt hij voor.e Ik denk, dat dit dezelfde persoon is, wiens naam in het eerste stuk wegens onduidelijk schrift voor S. Scotus is aangezien, terwijl Scholtetus bedoeld zal zijn. In aug. 1606 was dr. Carolus Crantz medisch doctor en rector te Joure; in 1611 heet hij dr. Carolus Cardanus en was een van de collatoren van het O.L. Vrouwe ter Noodt Leen te Franeker.f Ook in 1615 was hij hier nog rector. Joure ontving jaarlijks 150 c.g. van de Staten voor zijn rector. De school bloeide: op 30 juli 1619 is er zelfs sprake van een conrector, Mr. Dirck Dircks genaamd, "nu ter tijd wonende op de Joure".g Van 1623 tot 1628 vinden we Tietgerus Ruwardi Schotanus als rector te Joure vermeld,h maar in aug. 1629 is het weer Carel Crantz. Op 17 juni 1637 trouwde Carel Crantz, van Leeuwarden afkomstig, medisch doctor en rector in Joure, met Trijntje Gerrijts Leboer van Teecklenburg. -

Toelichting BP BK-Zuivelfabriek

Gemeente Heerenveen Bestemmingsplan Bontebok – inbreidingslokatie Zuivelfabriek Gemeente Heerenveen INHOUD 1. INLEIDING 4 2. HUIDIGE SITUATIE 5 2.1 De ruimtelijke-functionele structuur 5 2.2 De omgeving van de voormalige zuivelfabriek 5 3. BELEIDSKADER 6 3.1 Provinciaal beleid 6 3.2 Gemeentelijk beleid 7 4. STEDENBOUWKUNDIGE UITGANGSPUNTEN 10 4.1 inleiding 10 4.2 Randvoorwaarden en intentie 10 5. RANDVOORWAARDEN VANUIT DE OMGEVINGSFACTOREN 12 5.1 Ecologie 12 5.2 Archeologie 13 5.3 Water 14 5.4 Milieuaspecten 15 5.5 Externe veiligheid 16 5.6 Bodem 17 6. JURIDISCHE TOELICHTING 18 6.1 De plansystematiek 18 6.2 De bestemmingen 19 7. INSPRAAK EN OVERLEG 21 7.1 Inleiding 21 7.2 Inspraakprocedure 21 7.3 Resultaten inspraak 22 7.4 Resulaten vooroverleg ex artikel 3.1.1 23 Bestemmingsplan Zuivelfabriek blz. 3 Status: ontwerp Gemeente Heerenveen 1. INLEIDING Dit bestemmingsplan voorziet in een herziening van het geldende bestemmingsplan “Bontebok” voor wat betreft het terrein van de voormalige zuivelfabriek in de kern van het dorp, op het perceel kadastraal bekend gemeente Mildam, sectie J, nr. 1524 (grotendeels). De ligging van het terrein is in figuur 1 aangeduid. Het bestemmingsplan “Bontebok” is vastgesteld door de gemeenteraad van Heerenveen op 22 maart 1982 en goedgekeurd door het college van Gedeputeerde Staten van Fryslân op 13 maart 1983. Deze herziening van het bestemmingsplan “Bontebok” beoogt de bouw mogelijk te maken van maximaal negen woningen op het terrein van de oude zuivelfabriek. Deze herziening is noodzakelijk omdat op grond van het geldende bestemmingsplan de bouw van deze woningen niet is toegestaan. -

01 Baanwedstrijd Meisjes Pupillen 2

01 Baanwedstrijd meisjes pupillen 2 2e baanwedstrijd - Heerenveen 4-11-2019 Daguitslag Meisjes Pupillen pos nr naam woonplaats sponsor rnd grp pnt 1 36 Marika de Glee Rottum 2 1 Willeke Bouwhuis Steggerda 3 32 Esther Korenberg Kamperveen 4 28 Nora Lieke de Vries Leeuwarden 5 34 Nienke Valkenburg Boornbergum 6 27 Anouk Cnossen Luinjeberd 7 38 Laura de Vries Sint Nicolaasga 8 29 Elbrich de Jager Tirns 9 30 Amber Wietsma Nijeveen 10 40 Femke Boskma Harlingen 11 37 Rianne van der Leij Haskerdijken 12 35 Freya Goerres Aldeboarn 13 31 Emma Pit Nijeveen 14 26 Nine Brecht Oosterhof Engwierum 15 33 Carlijn Kroon Mildam 16 39 Janine Postma Idskenhuizen 1-12-2019 11:00:33 8rnd 3km 1 van 1 Baanwedstrijd DPA 2 2e baanwedstrijd - Heerenveen 4-11-2019 Daguitslag Meisjes Pupillen pos nr naam woonplaats sponsor rnd grp pnt 1 36 Marika de Glee Rottum 15,1 1 Willeke Bouwhuis Steggerda 2 32 Esther Korenberg Kamperveen 14 3 28 Nora Lieke de Vries Leeuwarden 13 4 34 Nienke Valkenburg Boornbergum 12 5 27 Anouk Cnossen Luinjeberd 11 6 38 Laura de Vries Sint Nicolaasga 10 7 29 Elbrich de Jager Tirns 9 30 Amber Wietsma Nijeveen 8 40 Femke Boskma Harlingen 8 9 37 Rianne van der Leij Haskerdijken 7 35 Freya Goerres Aldeboarn 31 Emma Pit Nijeveen 26 Nine Brecht Oosterhof Engwierum 10 33 Carlijn Kroon Mildam 6 11 39 Janine Postma Idskenhuizen 5 1-12-2019 11:00:35 8rnd 3km 1 van 1 Tussenklassement Seizoen: 2019-2020 Baan Meisjes Pupillen A - Baanwedstrijd DPA t/m wedstrijd 2 (4-11-2019) pos nr naam woonplaats sponsor aft pnt 1 28 Nora Lieke de Vries Leeuwarden 28,1