Endocrine Oncology Thyroid Carcinoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors and Modifications of Thyroid Function Tests

European Journal of Endocrinology (2009) 160 331–336 ISSN 0804-4643 REVIEW Tyrosine kinase inhibitors and modifications of thyroid function tests: a review Fre´de´ric Illouz1,2, Sandrine Laboureau-Soares1,Se´verine Dubois1, Vincent Rohmer1,2,3,4 and Patrice Rodien1,2,3,4 1CHU d’Angers, De´partement d’Endocrinologie Diabe´tologie Nutrition, Angers Cedex 09 F-49933, France, 2Centre de Re´fe´rence des Pathologies de la Re´ceptivite´ Hormonale, CHU d’Angers, Angers Cedex 09 F-49933, France, 3INSERM, U694, Angers Cedex 09 F-49933, France and 4Universite´ d’Angers, Angers Cedex 09 F-49933, France (Correspondence should be addressed to F Illouz; Email: [email protected]) Abstract Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) belong to new molecular multi-targeted therapies that are approved for the treatment of haematological and solid tumours. They interact with a large variety of protein tyrosine kinases involved in oncogenesis. In 2005, the first case of hypothyroidism was described and since then, some data have been published and have confirmed that TKI can affect the thyroid function tests (TFT). This review analyses the present clinical and fundamental findings about the effects of TKI on the thyroid function. Various hypotheses have been proposed to explain the effect of TKI on the thyroid function but those are mainly based on clinical observations. Moreover, it appears that TKI could alter the thyroid hormone regulation by mechanisms that are specific to each molecule. The present propositions for the management of TKI-induced hypothyroidism suggest that we assess the TFT of the patients regularly before and during the treatment by TKI. -

Lenvatinib in Advanced, Radioactive Iodine– Refractory, Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma Kay T

Published OnlineFirst October 20, 2015; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0923 CCR Drug Updates Clinical Cancer Research Lenvatinib in Advanced, Radioactive Iodine– Refractory, Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma Kay T. Yeung1 and Ezra E.W. Cohen2 Abstract Management options are limited for patients with radioactive therapy for these patients. Median PFS of 18.3 months in the iodine refractory, locally advanced, or metastatic differentiated lenvatinib group was significantly improved from 3.6 months in thyroid carcinoma. Prior to 2015, sorafenib, a multitargeted the placebo group, with an HR of 0.21 (95% confidence interval, tyrosine kinase inhibitor, was the only approved treatment and 0.4–0.31; P < 0.0001). ORR was also significantly increased in the was associated with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of lenvatinib arm (64.7%) compared with placebo (1.5%). In this 11 months and overall response rate (ORR) of 12% in a phase III article, we will review the molecular mechanisms of lenvatinib, trial. Lenvatinib, a multikinase inhibitor with high potency the data from preclinical studies to the recent phase III clinical against VEGFR and FGFR demonstrated encouraging results in trial, and the biomarkers being studied to further guide patient phase II trials. Recently, the pivotal SELECT trial provided the selection and predict treatment response. Clin Cancer Res; 21(24); basis for the FDA approval of lenvatinib as a second targeted 5420–6. Ó2015 AACR. Introduction PI3K–mTOR pathways (reviewed in ref. 3). The signals ultimately converge in the nucleus, influencing transcription of oncogenic Thyroid carcinoma is the most common endocrine malignan- proteins including, but not limited to, NF-kB), hypoxia-induced cy, with an estimated incidence rate of 13.5 per 100,000 people factor 1 alpha unit (HIF1a), TGFb, VEGF, and FGF. -

TE INI (19 ) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication ( 10) Pub

US 20200187851A1TE INI (19 ) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication ( 10) Pub . No .: US 2020/0187851 A1 Offenbacher et al. (43 ) Pub . Date : Jun . 18 , 2020 ( 54 ) PERIODONTAL DISEASE STRATIFICATION (52 ) U.S. CI. AND USES THEREOF CPC A61B 5/4552 (2013.01 ) ; G16H 20/10 ( 71) Applicant: The University of North Carolina at ( 2018.01) ; A61B 5/7275 ( 2013.01) ; A61B Chapel Hill , Chapel Hill , NC (US ) 5/7264 ( 2013.01 ) ( 72 ) Inventors: Steven Offenbacher, Chapel Hill , NC (US ) ; Thiago Morelli , Durham , NC ( 57 ) ABSTRACT (US ) ; Kevin Lee Moss, Graham , NC ( US ) ; James Douglas Beck , Chapel Described herein are methods of classifying periodontal Hill , NC (US ) patients and individual teeth . For example , disclosed is a method of diagnosing periodontal disease and / or risk of ( 21) Appl. No .: 16 /713,874 tooth loss in a subject that involves classifying teeth into one of 7 classes of periodontal disease. The method can include ( 22 ) Filed : Dec. 13 , 2019 the step of performing a dental examination on a patient and Related U.S. Application Data determining a periodontal profile class ( PPC ) . The method can further include the step of determining for each tooth a ( 60 ) Provisional application No.62 / 780,675 , filed on Dec. Tooth Profile Class ( TPC ) . The PPC and TPC can be used 17 , 2018 together to generate a composite risk score for an individual, which is referred to herein as the Index of Periodontal Risk Publication Classification ( IPR ) . In some embodiments , each stage of the disclosed (51 ) Int. Cl. PPC system is characterized by unique single nucleotide A61B 5/00 ( 2006.01 ) polymorphisms (SNPs ) associated with unique pathways , G16H 20/10 ( 2006.01 ) identifying unique druggable targets for each stage . -

Phase II Study of Motesanib in Japanese Patients with Advanced Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors with Prior Exposure to Imatinib Mesylate

Cancer Chemother Pharmacol (2010) 65:961–967 DOI 10.1007/s00280-009-1103-9 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Phase II study of motesanib in Japanese patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors with prior exposure to imatinib mesylate Akira Sawaki · Yasuhide Yamada · Yoshito Komatsu · Tatsuo Kanda · Toshihiko Doi · Masato Koseki · Hideo Baba · Yu-Nien Sun · Koji Murakami · Toshirou Nishida Received: 24 May 2009 / Accepted: 29 July 2009 / Published online: 19 August 2009 © The Author(s) 2009. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Purpose Motesanib (AMG 706) is a multitargeted anti- Adverse Events (version 3). cancer agent with an inhibitory action on the human vascu- Results Of 35 enrolled and treated patients, no patient lar endothelial growth factor receptor, the platelet-derived showed a complete response, and one patient showed a par- growth factor receptor, and the cellular stem-cell factor tial response (PR). Seven had stable disease (SD) for at receptor (KIT). The aim of this single-arm phase II clinical least 24 months, two of whom continued to have SD for study was to assess the eYcacy and safety of single-agent more than 2 years. The median progression-free survival motesanib in Japanese patients with advanced gastrointesti- time was 16.1 weeks. Motesanib was well tolerated; com- nal stromal tumors with prior exposure to imatinib monly reported treatment-related adverse events were mesylate. hypertension, diarrhea, and fatigue. Anemia was the only Methods All patients had experienced progression or hematological toxicity that was reported. relapse while undergoing with imatinib as 400 mg/day or Conclusions One patient showed PR, and seven patients higher. -

Endoperspectives, Volume 5, Issue 2

Department of Endocrine Neoplasia and Hormonal Disorders NEWSLETTER Volume 5, Issue 2, 2012 Metastatic Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: When is Systemic Therapy Beyond RAI Warranted? ® Maria E. Cabanillas, MD Assistant Professor Department of Endocrine Neoplasia and Hormonal Disorders Introduction consideration of local therapy or systemic treatment Patients with widely meta- with the newer tyrosine kinase inhibitors or cytotoxic static differentiated thyroid chemotherapy is appropriate once significant progres- cancer (DTC; includes papil- sion is documented. Figure 1 shows the algorithm for lary, follicular, and Hurthle cell treatment of patients who present with metastatic dis- carcinoma) can pose a chal- ease and those who later develop metastatic disease lenge to physicians, especially after first line therapy. those who see few cases of Definition of RAI-refractory this relatively rare presenta- A patient is considered RAI-refractory when radioio- tion. While the 10 year median survival after the dis- dine is no longer effective either because the disease covery of metastatic disease is 42%, the prognosis can does not take up iodine (usually determined on a pre- or be vastly different among patients and depends on the post-treatment, diagnostic whole body scan) at known age of patient, histology, location and size of the dis- sites of metastatic disease or because the disease con- tant disease, as well as whether the disease takes up tinues to grow despite previous treatment. Radioiodine and responds to radioactive iodine (RAI)1. For example, can continue to have efficacy over 9-12 months (some- younger patients (<40 years) with micronodular (<1cm) times longer) and therefore the patient is considered lung disease have an excellent overall survival of 95% at RAI-refractory only when the distant disease grows over 10 years, while older patients with macronodular lung a 1 year period after RAI. -

Free PDF Download

Microb Health Dis 2021; 3: e531 REVIEW – RECENT NEWS ON PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF GASTRIC CANCER G. Pasi, T. Matysiak-Budnik IMAD, Hepato-Gastroenterology & Digestive Oncology, University Hospital of Nantes, Nantes, France Corresponding Author: Tamara Matysiak-Budnik, MD; email: [email protected] Abstract: Despite its decreasing incidence, gastric cancer (GC) is still the third leading cause of cancer death in the world. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori has been shown to decrease the risk of GC, without evidence of adverse consequences. Operable GC is treated with surgery, and laparoscopic gastrectomy has proven to be a valid alternative to open gastrectomy. For advanced GC, the available therapies show limited benefit in extending survival, but some new approaches are emerging, like immunotherapy using immune checkpoint inhibitors which, in combination with chemotherapy, has been shown to increase survival. In this article, we review the most relevant articles concerning GC prevention and treatment published between April 2020 and March 2021. Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Screening, Prevention, Immunotherapy, Laparoscopy. INTRODUCTION Gastric cancer (GC) is the third leading cause of cancer death in the world, and despite a decline in its incidence, it remains a major public health problem on a global scale. The impact of massive H. pylori eradication on GC prevention has been debated, and recent data further confirm the efficacy of this approach. In the treatment of advanced GC, promising results have been obtained with new targeted therapies and immunotherapies using checkpoint inhibitors. The safety of laparoscopic gastrectomy has been further supported. An innovative molecular approach for the detection of residual disease after surgery based on liquid biopsy has been proposed. -

The Effect of Different Dosing Regimens of Motesanib on the Gallbladder: a Randomized Phase 1B Study in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title The effect of different dosing regimens of motesanib on the gallbladder: a randomized phase 1b study in patients with advanced solid tumors Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5j47k5v4 Journal BMC Cancer, 13(1) ISSN 1471-2407 Authors Rosen, Lee S Lipton, Lara Price, Timothy J et al. Publication Date 2013-05-16 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-242 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Rosen et al. BMC Cancer 2013, 13:242 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/13/242 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The effect of different dosing regimens of motesanib on the gallbladder: a randomized phase 1b study in patients with advanced solid tumors Lee S Rosen1*, Lara Lipton2, Timothy J Price3, Neil D Belman4, Ralph V Boccia5, Herbert I Hurwitz6, Joe J Stephenson Jr7, Lori J Wirth8, Sheryl McCoy9, Yong-jiang Hei10, Cheng-Pang Hsu11 and Niall C Tebbutt12 Abstract Background: Gallbladder toxicity, including cholecystitis, has been reported with motesanib, an orally administered small-molecule antagonist of VEGFRs 1, 2 and 3; PDGFR; and Kit. We assessed effects of motesanib on gallbladder size and function. Methods: Patients with advanced metastatic solid tumors ineligible for or progressing on standard-of-care therapies with no history of cholecystitis or biliary disease were randomized 2:1:1 to receive motesanib 125 mg once daily (Arm A); 75 mg twice daily (BID), 14-days-on/7-days-off (Arm B); or 75 mg BID, 5-days-on/2-days-off (Arm C). -

Your Pharmacy Benefits Welcome to Your Pharmacy Plan

Your Pharmacy Benefits Welcome to Your Pharmacy Plan OptumRx manages your pharmacy benefits for your health plan sponsor. We look forward to helping you make informed decisions about medicines for you and your family. Please review this information to better understand your pharmacy benefit plan. Using Your Member ID Card You can use your pharmacy benefit ID card at any pharmacy participating in your plan’s pharmacy network. Show your ID card each time you fill a prescription at a network pharmacy. They will enter your card information and automatically file it with OptumRx. Your pharmacy will then collect your share of the payment. Your Pharmacy Network Your plan’s pharmacy network includes more than 67,000 independent and chain retail pharmacies nationwide. To find a network pharmacy near you, use the Locate a Pharmacy tool at www.optumrx.com. Or call Customer Service at 1-877-559-2955. Using Non -Network Pharmacies If you do not show the pharmacy your member ID card, or you fill a prescription at a non-network pharmacy, you must pay 100 percent of the pharmacy’s price for the drug. If the drug is covered by your plan, you can be reimbursed. To be reimbursed for eligible prescriptions, simply fill out and send a Direct Member Reimbursement Form with the pharmacy receipt(s) to OptumRx. Reimbursement amounts are based on contracted pharmacy rates minus your copayment or coinsurance. For a copy of the form, go to www.optumrx.com. Or call the Customer Service number above. The number is also on the back of your ID card. -

Lenvatinib with Everolimus for Previously Treated Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma

Lenvatinib with everolimus for previously treated advanced renal cell carcinoma Technology appraisal guidance Published: 24 January 2018 www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta498 © NICE 2020. All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights (https://www.nice.org.uk/terms-and-conditions#notice-of- rights). Lenvatinib with everolimus for previously treated advanced renal cell carcinoma (TA498) Your responsibility The recommendations in this guidance represent the view of NICE, arrived at after careful consideration of the evidence available. When exercising their judgement, health professionals are expected to take this guidance fully into account, alongside the individual needs, preferences and values of their patients. The application of the recommendations in this guidance are at the discretion of health professionals and their individual patients and do not override the responsibility of healthcare professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient and/or their carer or guardian. Commissioners and/or providers have a responsibility to provide the funding required to enable the guidance to be applied when individual health professionals and their patients wish to use it, in accordance with the NHS Constitution. They should do so in light of their duties to have due regard to the need to eliminate unlawful discrimination, to advance equality of opportunity and to reduce health inequalities. Commissioners and providers have a responsibility to promote an environmentally sustainable health and care system and should assess and reduce the environmental impact of implementing NICE recommendations wherever possible. © NICE 2020. All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights (https://www.nice.org.uk/terms-and- Page 2 of conditions#notice-of-rights). -

A Review on Newer Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors and Their Uses Oncology Section Oncology

DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2018/31031.11957 Review Article A Review on Newer Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors and their Uses Oncology Section Oncology NITHU M KUMAR1, MEENU MATHEW2, KN ANILA3, S PRIYANKA4 ABSTRACT Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKI) can reversibly or irreversibly block the signaling pathway occurring in the extracellular part of the receptor by inhibiting Tyrosine Kinase (TK) phosphorylation. This review included the drugs that were newly marketed or drugs with newer approved uses after 2015, such as Gefitinib, Osimertinib, Crizotinib, Alectinib, Ibrutinib, Cabozantinib. Brigatinib and Lorlatinib are investigational drugs that have not been approved and have shown promising results in trials for the treatment of Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK) positive metastatic Non Small Cell Lung Carcinoma (NSCLC). Gefitinib, Osimertinib, Crizotinib, Alectinib were approved for treating NSCLC. Cabozantinib and Lenvatinib were approved for treating renal cell carcinoma and thyroid carcinoma. Ibrutinib was approved for treatment of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia, Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, previously treated Mantle cell lymphoma and relapsed or refractory Marginal zone lymphoma. TKI have promising efficacy in treating a wide range of oncologic diseases. Hand-foot-skin reaction are the most common side effect of drugs in this category, however, TKI are found to have relatively fewer side effects compared to other anti cancer drugs. Keywords: Anaplastic lymphoma kinase, Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitor, Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor, Non small cell lung carcinoma, Vascular endothelial growth factor INTRODUCTION In this review we have given a generalized insight into the anti Cancer kinome is now recognized as potential target for treating cancer activity, mechanism of action, and adverse drug reaction of cancer and comprise of more than 500 members where only few TK whose clinical activity have been fairly understood. -

Effect of Kinase Inhibitors on the Technetium-99M Uptake Into Thyroid Carcinoma Cells in Vitro ANNA ANSCHLAG 1, BRANDON H

in vivo 35 : 721-729 (2021) doi:10.21873/invivo.12313 Effect of Kinase Inhibitors on the Technetium-99m Uptake into Thyroid Carcinoma Cells In Vitro ANNA ANSCHLAG 1, BRANDON H. GREENE 2, LORIANNA KÖNNEKER 3, MARKUS LUSTER 4, JAMES NAGARAJAH 5, SABINE WÄCHTER 6, ANNETTE WUNDERLICH 6 and ANDREAS PFESTROFF 4 1Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University Hospital of Marburg, Marburg, Germany; 2Bio 21 Institute, CSL Limited Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia; 3Department of Virology, Hospital Nordwest Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany; 4Department of Nuclear Medicine, University Hospital of Marburg, Marburg, Germany; 5Department of Nuclear Medicine, Klinikum Rechts der Isar, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany; 6Department of Visceral, Thoracic and Vascular Surgery, University Hospital of Marburg, Marburg, Germany Abstract. Background/Aim: We evaluated the potential of the distribution between the genders, and above 45,000 deaths kinase inhibitors sorafenib, lenvatinib and selumetinib on were recorded globally due to malignant thyroid disease (2). increasing the uptake of technetium-99m into thyroid cancer Its manifestations can be subdivided into different categories. cells. Materials and Methods: Four established cell lines and Differentiated thyroid carcinomas (DTC), accounting for about three patient’s cell cultures were treated with 0.1, 1 and 5μM 85% of all thyroid cancers, derive from the follicular of sorafenib, lenvatinib and selumetinib for 72 hours. After epithelium and include papillary (PTC) as well as follicular incubation with 1 MBq of technetium-99m, the radioactivity thyroid carcinoma (FTC), and a couple of rare subtypes. uptake was measured. Results: The experiments showed Medullary thyroid cancers (MTC) are developed from heterogeneous results. Maximum technetium-99m uptake calcitonin producing C-cells, whereas the highly aggressive increases of 312% (sorafenib), 326% (lenvatinib) and 759% anaplastic thyroid carcinomas (ATC) are composed of (selumetinib) were obtained using the highest applied dedifferentiated tissue. -

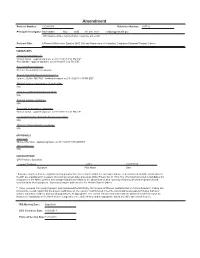

Amendment Protocol Number: 12C0079-R Reference Number: 365732

Amendment Protocol Number: 12C0079-R Reference Number: 365732 Principal Investigator: Ravi Madan NCI GMB 301.480.7168 [email protected] (NIH Employee Name, Institute/Branch, Telephone and e-mail) Protocol Title: A Phase II Multicenter Study of AMG 386 and Abiraterone in Metastatic Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer SIGNATURES Principal Investigator (*): William Dahut - applied signature on 01/12/2017 4:52 PM EST Ravi Madan - applied signature on 01/11/2017 5:32 PM EST Accountable Investigator: PI is the Accountable Investigator Branch Chief/CC Department Head (**): James L Gulley, MD PhD - applied signature on 01/11/2017 4:37 PM EST Medical Advisory Investigator (if applicable): N/A Lead Associate Investigator signature: N/A Referral Contact signatures: N/A Associate Investigators signatures: William Dahut - applied signature on 01/12/2017 4:52 PM EST For Institute/Center Scientific Review Committee: N/A Other IC Clinical Director signatures: N/A APPROVALS IRB Chair: Michael Hamilton - applied signature on 01/18/2017 9:55 AM EST Clinical Director: N/A CONCURRENCE OPS Protocol Specialist: Lemuel Clayborn AM R 01/27/2017 Signature Print Name Date * Signature signifies that investigators on this protocol have been informed that the collection and use of personally identifiable information at the NIH are maintained in a system of record governed under provisions of the Privacy Act of 1974. The information provided is mandatory for employees of the NIH to perform their assigned duties as related to the administration and reporting of intramural research protocols and used solely for those purposes. Questions may be addressed to the Protrak System Owner.