Ronald Davis Is Not Doing What You're Seeing Dave Hickey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modernism 1 Modernism

Modernism 1 Modernism Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modernism was a revolt against the conservative values of realism.[2] [3] [4] Arguably the most paradigmatic motive of modernism is the rejection of tradition and its reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody in new forms.[5] [6] [7] Modernism rejected the lingering certainty of Enlightenment thinking and also rejected the existence of a compassionate, all-powerful Creator God.[8] [9] In general, the term modernism encompasses the activities and output of those who felt the "traditional" forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, social organization and daily life were becoming outdated in the new economic, social, and political conditions of an Hans Hofmann, "The Gate", 1959–1960, emerging fully industrialized world. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 collection: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. injunction to "Make it new!" was paradigmatic of the movement's Hofmann was renowned not only as an artist but approach towards the obsolete. Another paradigmatic exhortation was also as a teacher of art, and a modernist theorist articulated by philosopher and composer Theodor Adorno, who, in the both in his native Germany and later in the U.S. During the 1930s in New York and California he 1940s, challenged conventional surface coherence and appearance of introduced modernism and modernist theories to [10] harmony typical of the rationality of Enlightenment thinking. -

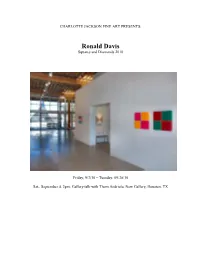

Ronald Davis Squares and Diamonds 2010

CHARLOTTE JACKSON FINE ART PRESENTS: Ronald Davis Squares and Diamonds 2010 Friday, 9/3/10 – Tuesday, 09/28/10 Sat., September 4, 3pm: Gallery talk with Thom Andriola, New Gallery, Houston, TX Art was Ronald Davis’ third choice; he wanted to be a race car driver. But after a few crashes and near misses, the young Davis realized that racing was both expensive and dangerous. He switched to painting, leaving the wide-open spaces of Wyoming for the fog-shrouded San Francisco Art Institute though, as he says, “Later I found out that being an artist is much more dangerous – and just as expensive.” The paintings he brings to this exhibition of new work, Squares and Diamonds 2010, may be a bit dangerous for the viewer. They are highly charged, vibrating with energy—something unexpected in paintings of geometrical abstraction. In Interlocked Square a golden knot is suspended precariously over a quickly-receding blue void. In Black Diamond the viewer stares into a twisting diamond of black space through an off-kilter frame of interlocking pastel polygons. Orange Bevel Square simultaneously pops inward and outward at the viewer, writhing uncomfortably off center and out of perspective. There are illusions within the illusions here; some of the optical effects of the paintings are created strictly by the manipulation of form and color on a square piece of expanded PVC. However, in some pieces what seems to be another perfect square or diamond is not: there are bevels and bends in the PVC skillfully incorporated into the composition to add to the perceptual distortions. -

Andrea-Foenander-ART 1990-Essay

The LA ACM/SIGGRAPH 1990 exhibition at EZTV By Andrea Foenander Aim; to discuss how the LA ACM/SIGGRAPH 1990 show at EZTV, 18th Street Arts Center, Santa Monica CA, marks the naissance of the term Computer Artist and speculate the idleness of this term thereafter. Method; Analysis of contributing artists within the context of social and economic factors through primary and secondary research. Significance; Now that censorship grows in rivalry of the open source movement, contemporary art seeks to revive the utopian perception of Computer Art. It is an important time to reflect upon the history of the Computer Artist. [Fig. 1] Above is a still from the website banner produced by Victor Acevedo, member of the DigiLantes1, used for a retrospective at EZTV gallery in 1997. Contents p.3 Introduction p.7. Catalogue of Contributing Artists p.8. Breeding Cyborg’s: The Terminator p.14. SIGGRAPH: E-Commerce p.19. Performative Activism p.25. Technology fetishized p.31. A Lost Aesthetic p.37. Conclusion p.40. Bibliographies p.45. Appendix p.46. Index 1 The name DigiLantes was coined by artist Michael Wright to describe a group of artists pioneering digital media. Many of the Digilantes organized and exhibited in the LA ACM/SIGGRAPH 1990. 2 2 [Fig. 2.] EZTV Gallery (1990). LA 1990 Art Catalogue scan. Introduction. Computers use algorithms to formulate decisions. These outcomes are dependent upon the way the algorithms have been written by a programmer or designer. In a similar way, history is often said to have a certain degree of inevitability, with trends forming circuitry patterns. -

Light and Space” and “Finish Fetish” Artists

RARE OPPORTUNITY ON THE EAST COAST TO VIEW COMPREHENSIVE EXHIBIT OF WORK FROM SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA-BASED “LIGHT AND SPACE” AND “FINISH FETISH” ARTISTS Light, Space, Surface Opens at the Addison Gallery of American Art on November 23, 2021 Features Artists Including Mary Corse, Bruce Nauman, Helen Pashgian, and James Turrell Andover, MA (August 12, 2021) – Light, Space, Surface: Works from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art will offer museumgoers the opportunity to experience a distinctly West Coast style of art on the East Coast, presenting the art of Light and Space and related “finish fetish” works with highly polished surfaces. The exhibition, which opens at the Addison Gallery of American Art on November 23, 2021, is one of the most comprehensive ever assembled of these artists and highlights works that explore perceptual phenomena via interactions with light and space. Drawn from the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Light, Space, Surface features a wide range of media, from painting and sculpture to immersive environments. “It’s a privilege to be able to present this important period of American artistic innovation—often thought of as Minimalism with a uniquely Californian twist—here on the East Coast,” said Allison Kemmerer, the interim director of the Addison Gallery of American Art, Mead Curator of Photography, and senior curator of contemporary art. “Transforming the viewer from passive observer to active participant, the reflective surfaces, glossy finishes, and shimmering colors of these works demand -

Sunshine and Shadow: Recent Painting in Southern California Exhibition Dates: 15 January-23 February 1985

Sunshine and Shadow: Recent Painting in Southern California Exhibition Dates: 15 January-23 February 1985 2500 copies printed on the occasion of the exhibition, Sunshine and Shadow: Recent Painting in Southern California, at the Fisher Gallery, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California. Catalog design: Nancy Zaslavsky, Ultragraphics, Venice, California Design assistant: Lupe Marmolejo Assistant to the curator: Joanne Rattner Catalog editor: Jeanne D ’Andrea Photography: Damian Andrus - pp. 17, 43; Art Documentation - pp. 15, 23, 2 7 . -29. 33. 37. 45. 53. 59, 61, 67; J. Felgar - pp. 47, 5.; L.A. Louver - pp. 55, 71; Barbara Lyter - p. 35; Modernism - p. 39; Douglas M. Parker Studio - pp. 21, 37; Ernest Silva - p. 69. Typographer: Mondo Typo, Santa Monica, California Typography: Garamond with small caps; Univers 85 Lithography: Southern California Graphics, Culver City, California Text paper: 100 pound Centura Cover paper: .018 pt. Carolina © 1985 by the Fellows of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, California All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this catalog may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means without permission in writing from the Fellows of Contemporary Art, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. Published by the Fellows of Contemporary Art, 333 South Hope Street, 48th Floor, Los Angeles, California 90071. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 84-73006 isbn 0-911291-10-5 Sunshine and Shadow: Recent Painting in Southern California Susan C. Larsen An exhibition and catalog initiated and sponsored by the Fellows of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and organized by the Fisher Gallery, University of Southern California. -

Abstract Illusionism: Taking the Realism out of Illusion

James Havard, Flat Head River, 1976, acrylic on canvas, 72 x 96 inches. Louis K. Meisel Gallery. Abstract Illusionism: Taking the Realism out of Illusion Cassidy Garhart Velazquez Colorado State University ART695A Specialization Research Project Fall 2007 Figure 1 : Ronald Davis, Disk, 1968, Figure 2: Paul Sarkisian, Untitled #12, 1980 Figure 3: James Havard, Cafe Rico, 1979, moulded polyester resin and fiberglass, 62 acrylic, silkscreen, & glitter on canvas, 46 acrylic on canvas, 20 x 30 inches. x 132 inches, Dodecagon series. x 48 inches. "When the illusion is lost, art is hard to find." The work of the artists dubbed Abstract Illusionists heroically dealt with so many painting issues. Sometimes the beauty and lyrical painterly qualities of their work is overshadowed (to the untrained eye) as the observer unravels the visual complexities involved in the abstract depiction of space. Dimension always exists in abstraction, no matter how it may be concealed. It is the ironic honesty of Abstract Illusionism that ranks it among the great "isms" of twentieth century painting. I Andrea Marzell Los Angeles, California 1Posted to the abstract-art.com guest book in 1997. The www.abstract-art.com web page was founded and is maintained by Ronald Davis. 1 In September of 1976 the Paul Mellon Arts Center in Wallingford, Connecticut held the first "official" group exhibition of Abstract Illusionist paintings. 1 The show was organized by Louis K. Meisel who, together with Ivan Karp, coined the phrase "Abstract Illusionism".2 Meisel extends credit to Karp (owner of the O.K. Harris gallery) saying that Karp was the first to refer to the style as "illusionistic abstraction", but, in Meisel' s words, his own phrase "abstract illusionism" is the one that "stuck". -

Trend Spring07 001-032

Artist PROFILE BY RIC LUM | PHOTOS BY LEE CLOCKMAN “A Painting’s Just Gotta Look Better than the Wallpaper,” his essay for the 40-work retrospective Ronald Davis: Abstractions 1962–2002 at the Butler Institute of Art in Youngstown, Ohio, Davis wrote: “I really had no aspiration to be an artist. It was my third choice. I wanted to be a racer [racecar driver] . [but] I realized I might get killed doing this. That would have been okay at the time, but racing is a rich man’s sport, and I couldn’t afford it. So I switched to painting. Later I found out that being an artist is much more dangerous— and just as expensive.” Davis enrolled in the San Francisco Art Institute in 1960—which he describes as “therapy”—at the same time deferring conscription in the military. Attending the Art Institute from 1960 to 1964, he fell under the influence of the protean muscular abstract paintings of Clyfford Still and the Bay Area figurative works of David Park and Richard Diebenkorn. As a young artist, Davis felt he didn’t have anything to express, nor the commitment to do so. “There were issues,” he wrote in his essay, “of abstract Opening of Ron Davis’s first one-man show at the Nicholas Wilder Gallery in Los Angeles in October content and style problems.” His main concern “was how 1965. On the wall is Big Blue from the Monochromatic Shaped series (1965), Liquatex acrylic on to make a picture, not how to look at one.” canvas. Wilder is shown at left, kissing a visitor. -

Between Illusion and Theatricality: Rosalind Krauss, Michael Fried And

E‐ISSN 2237‐2660 Entre a Ilusão e a Teatralidade: Rosalind Krauss, Michael Fried e o Minimalismo Manoel Silvestre FriquesI, II IUniversidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro – UNIRIO, Rio de Janeiro/RJ, Brasil IIUniversidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro – UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro/RJ, Brasil RESUMO – Entre a Ilusão e a Teatralidade: Rosalind Krauss, Michael Fried e o Mini- malismo – O artigo investiga a questão da teatralidade do Minimalismo a partir das leituras críticas elaboradas por Michael Fried e Rosalind Krauss. Enquanto Krauss, desde o primeiro momento em que reflete sobre obras de Donald Judd e Dan Flavin, evidencia sua contradição fundamental – a presença da ilusão, a despeito de sua rejeição pelos artistas –, Fried atém-se ao pretenso literalismo dessas propostas, denominando-o de teatralidade. No texto, as duas abordagens serão confrontadas, extraindo-se delas os pontos de vista dos autores para a noção de teatralidade. Palavras-chave: Minimalismo. Rosalind Krauss. Michael Fried. Crítica de Arte. Teatralida- de. ABSTRACT – Between Illusion and Theatricality: Rosalind Krauss, Michael Fried and Minimalism – The article investigates Minimalism’s theatricality from the standpoint of Michael Fried’s and Rosalind Krauss’ critical readings. On the one hand, Krauss, from the very first moment in which she reflects on the works of Donald Judd and Dan Flavin, evidences their fundamental contradiction: the presence of the illusion, despite its rejection by the artists. On the other hand, Fried focuses on the alleged literalism of those projects, calling them theatricality. In the text, the two approaches will be confronted in order to explore the authors’ different views on the notion of theatricality. -

Feelers: the 24Th Drawing Show at the Boston Center for the Arts

Search... ! ARTICLES REVIEWS INTERVIEWS MULTIMEDIA ARCHIVE LISTINGS " ABOUT " SUPPORT BR&S " YOU ARE AT: Home » Magazine » Feature » Feelers: The 24th Drawing Show at the Boston Center for the Arts Feelers: The 24th Drawing Show at the Boston Center for the Arts # 0 BY SAMUEL ADAMS ON NOVEMBER 16, 2015 FEATURE, MAGAZINE, REVIEWS “Imagine a vast sheet of paper on which straight Lines, Triangles, Squares, Pentagons, Hexagons, and other figures, instead of remaining fixed in their places, move freely about, on or in the surface.” Thus begins Edwin Abbott’s 1884 novel Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, which reduces social classes to geometric forms, the more sides the higher the class. Touch is the primary faculty of perception in the novel. The narrator explains, “Our sense of touch, stimulated by necessity, and developed by long training, enables us to distinguish angles far more accurately than your sense of sight.” A common greeting in Flatland is, “Permit me to ask you to feel and be felt.” One must feel another to truly know his contours. SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTER The 24th Drawing Show at the Boston Center for the Arts, Feelers, takes its name and conceptual framework from Abbott’s novel. The drawing biennial includes sixty works by fifty-six artists in the Center’s Mills Gallery. All hew closely to the themes of line and touch, transcending a condition of flatness that the exhibition takes as drawing’s Your email address essential condition. In this sense, Feelers offers the inverse of Michael Fried’s 1967 Artforum article “Surface and Illusion,” which praised the way Ronald Davis achieved a painterly effect of flatness even in the sculptural media of Your first name plastic and fiberglass. -

Ronald Davis

Ronald Davis Born 1937 in Santa Monica, CA Lives and Works in Taos Studio, Taos, NM Selected Solo Exhibitions 2013 Pixel Dust Renderings, Charlotte Jackson Fine Art, Santa Fe, NM 2010 Ronald Davis: monochrome painting from the ‘60s, Franklin Parrasch Gallery, New York, NY Ronald Davis: Squares and Diamonds, Charlotte Jackson Fine Art, Santa Fe, NM 2008 Paintings, 1966-2007, New Gallery, Houston, TX 3D CG, Eight Modern, Santa Fe, NM (catalogue) 2007 Ronald Davis: President’s Rooms, Eight Modern, Santa Fe, NM Ronald Davis: Five Decades: Past and Present Work, 1968 – 2007, Electric Works, San Francisco, CA (catalogue) Music Series: 1983-1985, Harwood Museum of Art, Taos, NM Ronald Davis: Flatland Series, New Gallery, Houston, TX 2006 Pixel Dust Paintings, New Gallery, Tom Andriola, Houston, TX (catalogue) 2005 Selected Paintings, 1974 – 2004, Galerie Dionisi, West Hollywood, CA Harwood Museum of Art, Taos, NM 2002 Forty Years of Abstraction: 1962-2002 – Major 40-painting career survey, Butler Institute Museum of American Art, Youngstown, OH (catalogue) Nushapes, Hinges, Diamonds, Victoria Meyhren Gallery, University of Denver, Denver, CO Hinge Series, Philip Bareiss Gallery, Taos, NM 1998 Jaquelin Loyd Gallery, Ranchos de Taos, NM 1991 DEL Fine Arts, Taos, NM BlumHelman Los Angeles, Santa Monica, CA 1989 Dodecagons, BlumHelman Los Angeles, Santa Monica, CA (catalogue) 1988 Spiral Series, BlumHelman New York, New York, NY 1987 Sedona Arts Center, Sedona AZ 1986 New York Academy of Sciences, New York, NY (catalogue) 1985 Graystone, San Francisco, CA 1984 BlumHelman Gallery, New York, NY Asher/Faure, Los Angeles, CA The Flatlanders, Thomas Babeor Gallery, La Jolla, CA 1983 Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles, CA Asher/Faure, Los Angeles, CA 1982 John Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco, CA Conejo Valley Art Museum, Thousand Oaks, CA Asher/Fauer, Los Angeles, CA 1981 BlumHelman Gallery, New York, NY Gemini G. -

Abstract Expressionism Guide: Table of Contents

Abstract Expressionism Guide: Table of Contents CONTENTS Guide One: Things to Know Background 2 Notable Abstract Expressionist Artists 3 Glossary 4 Talking About Abstract Expressionist Artworks 5 Guide Two: Things to See Abstract Expressionism at the Crocker 7 Sam Francis: A Brief Biography 10 Sam Francis for Students 11 Guide Three: Things to Do Art Activity: Color Field Painting 13 Art Activity: Action Painting 15 Art Activity: Texture Time! 17 Art Activity: Texture Time! 18 Writing/Research Project 20 Abstract Expressionism Guide: Background Abstract Expressionism is a modern art movement that them as a group, however, is almost misleading, since flourished in the post-World War II era, primarily in the their styles are significantly distinct from one another. United States. It includes mostly paintings, although some The artists weren’t organized in any formal way during sculpture and other art forms are associated with the style their lifetimes, and they were individually innovative as well. The artworks are non-representational, meaning along with being associated with a groundbreaking there are usually no recognizable objects depicted. Large movement. Pollock and Rothko, in fact, emerged as the canvases and visible texture are common characteristics preeminent figures in two very different types of Abstract of the paintings. Another is the tendency for the artist to Expressionist painting: gesture (or action) painting and use an “allover” style, filling the painting space without color field painting, respectively. creating a specific focal point. Color is perhaps the most striking and vital element—canvases saturated with one A lesser known but vital Abstract Expressionist movement or more intense colors are hallmarks. -

Ronald Davis

RonaldRonald DavisDavis Forty Years of Abstraction 1 9 6 2 - 2 0 0 2 FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Foreword he generation of artists of which Ronald Davis is a part has most exciting new media since the creation of oil paint. This, like made a lasting contribution to the field and in fact contin- the previous trendsetting departure from tradition, has shown the T ues to inspire the art of the new century. But very few of world that Ronald Davis should rank as one of the great innovators Davis’s contemporaries can claim to have affected the course of of the twentieth century and clearly is an artist whose work will events to the extent that this California-born painter has, in both ultimately help define the art of the new century. substance as well as style. And perhaps no other painter of his era On a personal level, this exhibition represents a special mom- explored media with as much intensity or investigated ent in my career. I have admired the work of Ronald new approaches to abstraction with such depth. Davis for nearly four decades since I first experienced Despite enormous success with his early, visually its amazing beauty and power at the Leo Castelli masterful canvases he pushed full speed ahead in Gallery. His work from that moment on would remain developing ways to express his ideas in newly devel- for me a standard of achievement by which I would oped resins, new material developed for industrial compare other abstract works. I am honored and most applications. These extraordinarily complex works proud that The Butler Institute of American Art would soon became among the most exhibited and critically play host to Ronald Davis’s first major museum show acclaimed works of the Post War era.