The War Against Tobacco a Progress Report from the Indian Front a Report from the Economist Intelligence Unit Sponsored by Pfizer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delhi Rape(E)

AUGUST 2013 ● ` 30 CHILD LABOUR FOR GO-AHEAD MEN IN INDIA: AND FAILINGFAILING LAWSLAWS DOMESTIC VIOLENCE: WOMEN SOFT TARGET ALONG THE ANCIENT ROUTE: REDISCOVERING GLORIOUS PAST WIMBLEDON 2013: RISING NEW STARS FIDDLING WITH AFSPA: APPEASEMENT IN DISGUISE INFANT MORTALITY: SHOCKING STATS INTERNATIONAL 10 10 50 years of women in space 73th year of publication. Estd. 1940 as CARAVAN 78 Their patience and perseverance paid off AUGUST 2013 No. 370 90 Massacre-squads NATIONAL 104 US to arm India! 20 ECONOMY ● ENTERPRISE 8 Ganging up of netas against electoral reforms 68 Just a mouse-click away 20 Child labour today 94 Closure of bank branches 23 Controlling child labour 95 An Idea can change your life 36 Another look at domestic 96 Solar energy highways violence MIND OVER MATTER 42 Dowry? 110 52 Demise of day-old infants in 26 Aunt relief India appaling 56 A heart-warming end to a 54 Stop fiddling with AFSPA harrowing journey 106 Elder abuse, some harsh facts 110 Aparta LIVING FEATURES 46 16 Are you in the middle rung? 4 Editorial 86 Fun Thoughts! 18 Creativity and failed love 13 My Pet Peeve 98 Viable solution 32 Are you caught into 14 Automobiles to parliament hung “I will do it later” Trap? Round the Globe (Poem) 46 India’s maverick missile woman 17 Human Grace 100 Women All 58 Discovering the origin of 29 Child Is A Child the Way Aryan Culture Is A Child 107 Shackles of 62 Doing yeoman service 30 The World in Superstition 64 Boxers’ pride 108 Pictures 109 My Most 66 Sassy & Sissy 34 Way in, Way out Embarrassing 72 Elegy to TMS 70 Gadgets & Gizmos Moment 74 Out of sight, not of mind 84 New Arrivals 113 Letters CONTENTS 76 Shamshad Begum 88 Visiting Srivilliputhur forest For some unavoidable reasons 92 From the diary of a ‘gigolo’ Photo Competition has to be dropped in this issue. -

Business Plan for Ayurveda Hospital Page 19

ARUN MAIRA ON WHY INDUSTRY MUST LEAD PAGE 15 VOL. 2 NO. 9 juLy 2005 Rs 50 BusIness pLan fOr ayurVeda HOspITaL Page 19 JOB RESERVATION DEBATE HOTS UP PRIVATE How Burning Brain won smoking ban Page 4 Ordinary people, SECTOR extraordinary lives Page 12 BILT gets award for community work Page 21 IN QUOTA Vanishing tigers, vanishing people Page 17 Healing power of dance therapy ARUNFA RORY, SUKHIADGEO THHORAT, T DIPANKAR Page 24 GUPTA, NARAYANA MURTY, CII vIEWS PEOPLE CAMPAIGNS NGO s SLOGANS CONTROvERSIES IDEAS vOLuNTEERS TRAINING BOOKS FILMS INTERvIEWS RESEARCH the best of civil society MICROFINANCE: DISCOVER THE NEW INDIAN BANKER PAGE 14 VOL. 2 NO. 7 MAY 2005 Rs 50 SHEILA DIKSHIT MAKES THE PDS WORK IN DELHI Mr EDITOR Page 4 HARIVANSH’S GUTSY JOURNALISM SELLS Tiger task force perfect: Narain Page 5 Mumbai land Rs 1.40 per sq foot! Page 19 A whole world on board Orbis Page 7 Baluchari sarees destroy weavers Page 8 Getting over the East India Company Page 17 Maira: Let’s talk about talking Page 18 Govt to liberalise community radio Page 6 VIEWS PEOPLE CAMPAIGNS NGOs SLOGANS CONTROVERSIES IDEAS VOLUNTEERS TRAINING BOOKS FILMS INTERVIEWS RESEARCH BECAUSE EVERYONE IS SOMEONE The magazine for people who care DO YOUR OWN THING SubScribe now ! rs 500 for 1 year rs 850 for 2 years rs 1200 for 3 years PAyMENT AND PERSONAL DETAILS MAKE A DIFFERENCE Name: Mr/Ms/Institution ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

5 National Organic Farming Convention

5th National Organic Farming Convention Mainstreaming Organic Farming 28th February 2015 - 2nd March 2015 | Chandigarh, India Proceedings Report Celebrating International Year of Soils for Sustaining Food and Farming Systems PATRONS: Bhartiya Jnanpith Laureate Dr Gurdial Singh Padma Bhushan Dr Inderjit Kaur Dr M P Poonia Key Organizers Report Prepared by: Anitha Reddy, Aritra Bhattacharya, Arunima Swain, Ashish Gupta, Bharat Mansata, Gursimran Kaur, Kavitha Kuruganti, Neha Jain, Neha Nagpal, Nyla Coelho, Parthasarathy VM, Praveen Narasingamurthy, Radhika Rammohan, Rajesh Krishnan, Ramasubramaniam, Sachin Desai, Satya Kannan, Sreedevi Lakshmikutty, Sumanas Koulagi, Tanushree Bhushan Photo Credits: Ashish Gupta, Jagadeesh, Kavitha Kuruganti, Ramasubramaniam, Shubhada Patil Organisers Alliance for Sustainable & Holistic Agriculture (ASHA), A-124/6, First Floor, Katwaria Sarai, New Delhi 100 016 Kheti Virasat Mission (KVM), #72, Street Number 4, R V Shanti Nagar, PO Box # 1, Jaitu 151202 Faridkot district, Punjab Organic Farming Association of India (OFAI), G-8, St. Britto’s Apartments, Feira Alta, Mapusa (Goa) 403 507 National Institute of Technical Teachers Training and Research (NITTTR), Sector 26, Chandigarh - 160 019 Other Contributors Centre for Sustainable Agriculture & Society for Agro-Ecology India Living Farms Sahaja Samrudha October 2015 Contents Background 1 Introduction 2 Objectives 3 Key Organizers 3 Other Partners 5 Highlights 6 Programme Structure 8 Main Convention | Feb 28 - Mar 2, 2015 9 Day One | Saturday | February 28, -

2 7 2006-IR1.Pdf

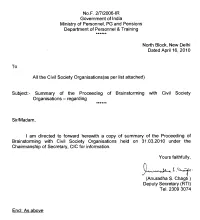

N0.F. 21712006-1R Government of India Ministry of Personnel. PG and Pensions Department of Personnel...*.. & Training North Block, New Delhi Dated April 16, 2010 To All the Civil Society Organisations(as per list attached) Subject:- Summary of the Proceeding of Brainstorming with Civil Society Organisations - regarding ....** I am directed to forward herewith a copy of summary of the Proceeding of Brainstorming with Civil Society Organisations held on 31.03.2010 under the Chairmanship of Secretary, CIC for information. Yours faithfully, - (Anuradha S. chagi ) Deputy Secretary (RTI) Tel. 2309 3074 Encl: As above Representative list of NGOs Shefali Chatuwedi Ms. Aruna Roy Director & Head- Social Development Mazdoor Kishan Sakthi Sangathan. Initiatives, Village Devdungri, Confederation of Indian Industry 249-F. Post Barar, District Rajsamand - 313341 Sector 18, Udyog Vihar, Phase IV. Rajasthan. 1 Guraaon - 122015. Ha~ana Te110124-401 4056 / 461 4060-67 Prof. Shekhar Singh Sh. Awind Kejariwal National Camoaiqn. - for Peoole's Riaht- Parivartan, ( to Information G-3/17, Sundernagari, 14, Tower 2, Supreme Enclave, Nandnagari Extn.. Delhi-110093 Mayur Vihar Phase-l Ph: 011- 221 19930 / 20033988 New Delhi - 110 091. Dr. Rajesh Tandon Ms. Maya Daruwala PRlA CHRl New Delhi Office NEW DELHl (Head Office) B-117, Second Floor, Sarvodaya Enclave 42, Tughlakabad Institutional Area, NewDelhi-110017 New Delhi - 1 10062 Tel: +91-11-2685-0523, 2652-8152. Tel: 29956908 / 29960931/32/33 / 2686-4678 hKumar I Dr. Yoaesh Kumar ' ~e~istra&Professor of Law National Law School of India University Centre for Development Support P.O. Bag 7201, Nagarbhavi, 36, Green Avenue, Chuna Bhatti, Kolar. Bangalore - 560 072. -

NOTES 1. Mentioning of Urgent Matters Will Be Before Hon'ble DB-I at 10.30 A.M. NOTICE in Terms of Directions Contained in Order

18.12.2017 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in INDEX PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGMENTS -----------------> 01 TO 02 REGULAR MATTERS ----------------------------> 01 TO 84 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) --------------> 01 TO 06 ADVANCE LIST -------------------------------> 01 TO 96 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)--------> 97 TO 134 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)---------> 135 TO 167 ORIGINAL SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY I)-------------> 168 TO 179 SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY -----------------------> 180 TO 186 COMPANY ------------------------------------> 187 TO 188 MEDIATION CAUSE LIST -----------------------> 1 TO 02 THIRD SUPPLEMENTARY -----------------------> TO NOTES 1. Mentioning of urgent matters will be before Hon'ble DB-I at 10.30 A.M. NOTICE In terms of directions contained in order dated 21.11.2017 passed in W.P.(C) 10362/2017 by Division bench comprising Hon'ble Mr. Justice S. Ravindra Bhat and Hon'ble Mr. Justice Sanjeev Sachdeva titled Independent Solar Power Producer Alliance Vs. Union of India & Ors, hereafter the memo of parties in every case should-wherever so available- list out the e-mail identities of every party to all manner of proceedings filed in Court. PRACTICE DIRECTIONS In terms of directions contained in order dated 26.10.2017 passed in W.P.(CRL.)1938/2017, hereafter, if not already done, every writ petition(which includes a PIL petition) filed in the Registry (and not obviously a letter or post card) should be supported by an affidavit which, apart from complying with the legal requirements in terms of the governing Rules of the High Court, should clearly state which part of the averments (with reference to para numbers or parts thereof) made (including those in the synopsis and list of dates and not just the petition itself) is true to the Petitioner's personal knowledge derived from records or based on some other source and what part is based on legal advice which the Petitioner believes to be true. -

Before the Hon'ble High Court of Punjab & Haryana at Chandigarh C.W. PETITION NO. 3131 of 2005 Hemant Goswami, (Chairper

Before the Hon’ble High Court of Punjab & Haryana at Chandigarh (IN THE INTEREST OF THE PUBLIC) C.W. PETITION NO. 3131 OF 2005 Hemant Goswami, (Chairperson) Burning Brain Society, A Society registered under the Societies Registration Act 1860 with administrative office at; #3, Glass Office, Shivalikview, Business Arcade, Sector 17-E, Chandigarh 160 017 ………………….Petitioner Versus Union of India & others ……….Respondents I N D E X S. No. Details Page No. 1 List of events Dt. 15-2-2005 3-4 2 Memo of Parties Dt. 15-2-2005 5-6 3 Synopsis Dt. 15-2-2005 7 4 Petition Dt. 15-2-2005 8-16 5 Affidavit Dt. 15-2-2005 17-18 6 Annexure P-1 Copy of Press Report from 19 “The Tribune” dated July 28, 2004 7 Annexure P-2 Copy of Press Report from 20 “The Times of India” dated July 28, 2004 8 Annexure P-3 Copy of a paid newspaper 21 advertisement of Red & White in a newspaper 9 Annexure P-4 Copy of complaint to IG, 22 Chandigarh Police 10 Annexure P-5 Copy of letter from the 23 office of IG, Chandigarh Police 11 Annexure P-6 Copy of cutting from 24 Hindustan Times, Dated January 18, 2005 12 Annexure P-7 Copy of cutting from Times 25 of Chandigarh, Dated January 18, 2005 2 13 Annexure P-8 Copy of cutting from 26 Hindustan Times, Dated January 18, 2005 14 Annexure P-9 Copy from Indian Express, 27 Dated January 18, 2005 15 Annexure P-10 Images of one side of Red 28 & White Cigarette packs 16 Annexure P-11 Pictures for comparison of 29 trademark and the brand names 17 Annexure P- 12 Copy of advertisement in 30-31 the newspaper Dainik Bhaskar on Feburary 13, 2005 and the translation 18 Annexure P-13 Compact Disc containing Attached(Details the soft copy of petition and (CD) at Page No. -

Legislation Process for Sub- National Smoke-Free Ordinances: Introduction to the “Twelve Steps”

Legislation process for sub- national smoke-free ordinances: introduction to the “Twelve Steps” Francisco Armada World Health Organization Centre for Health Development (WHO Kobe Centre) Twelve steps towards a smoke-free city 1. Set up a planning and implementation committee 2. Become an expert 3. Involve local legislative experts 4. Study several potential legal scenarios 5. Recruit political champions 6. Invite the participation of civil society organizations 7. Work with evaluation and monitoring experts 8. Engage with media and communications experts 9. Work closely with enforcement authorities 10. Develop and disseminate guidelines, signs, etc. 11. Celebrate the implementation day 12. Ensure maintenance of the law Making your city smoke-free – 12 steps to an effective smoke-free legislation 20 March 2012, Singapore 2 | 15th World Conference on Tobacco or Health Twelve steps: 1 Set up a planning and In Liverpool… implementation committee The city’s smoke-free initiative, SmokeFree Liverpool, was developed by the city’s local Chaired by the local health strategic partnership of public, private, authority voluntary and community-sector Members including: organizations – Civil society organizations (e.g. The initial steering group of the SmokeFree health, consumer, educational, Liverpool environmental, religious, or – Chaired by the Head of Environmental Health civic associations), and Trading Standards – Relevant enforcement – Included representatives from: authorities • Central, North and South Liverpool Primary Care Trusts; – -

REDUCING TOBACCO USE in South-East Asia Region Bloomberg Global Initiative

Vol. 1 No. 1, 2008 TFI Newsletter REDUCING TOBACCO USE in South-East Asia Region Bloomberg Global Initiative Every year, 1.2 million people in the South-East Asia Region die from tobacco-related illnesses Message from the Regional Director The Bloomberg Global Initiative (BGI) to Reduce Tobacco Use was I am pleased to learn that the Tobacco Free Initiative is established by Mr. Michael going to bring out a quarterly newsletter on the Bloomberg Bloomberg, Mayor of New York City, Global Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use. I appreciate this with a fund amounting to US$ 125 commendable effort as it would disseminate the information million to fight against the tobacco on activities and efforts being undertaken and good work epidemic. being done in our Region under the initiative. I am sure The initiative focuses on the that the newsletter will also serve as an advocacy tool following four components: and mechanism for information sharing and exchange in the Region among Refine and optimize tobacco the Bloomberg Foundation and the Bloomberg Partners. It should also control programmes to help enhance the knowledge of policy-makers and tobacco control stakeholders smokers stop and prevent children about the tobacco control efforts and opportunities provided by this from starting; important initiative. I also feel that the newsletter will demonstrate the support public sector efforts to transparency, accountability and efficiency with which this initiative is being pass and enforce key laws and implement effective policies, in carried out in the Region. particular to tax cigarettes, prevent I understand that the initiative works through definite, stated objectives smuggling, change the image of and outputs. -

Tobacco Control Policy Making: International

UCSF Tobacco Control Policy Making: International Title The Development and Implementation of Tobacco-Free Movie Rules In India Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/75j1b2cg Authors Yadav, Amit, PhD Glantz, Stanton A, PhD Publication Date 2020-12-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE DEVELOPMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF TOBACCO-FREE MOVIE RULES IN INDIA Amit Yadav, Ph.D. Stanton A. Glantz, Ph.D. Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education School of Medicine University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, CA 94143-1390 December 2020 THE DEVELOPMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF TOBACCO-FREE MOVIE RULES IN INDIA Amit Yadav, Ph.D. Stanton A. Glantz, Ph.D. Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education School of Medicine University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, CA 94143-1390 December 2020 This work was supported by National Cancer Institute grant CA-087472, the funding agency played no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the manuscript. Opinions expressed reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the sponsoring agency. This report is available on the World Wide Web at https://escholarship.org/uc/item/75j1b2cg. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • The Indian film industry releases the largest number of movies in the world, 1500-2000 movies in Hindi and other regional languages, which are watched by more than 2 billion Indian moviegoers and millions more worldwide. • The tobacco industry has been using movies to promote their products for over a century. • In India, the Cinematograph Act, 1952, and Cable Television Networks Amendment Act, 1994, nominally provide for regulation of tobacco imagery in film and TV, but the Ministry of Information and Broadcast (MoIB), the nodal ministry, has not considered tobacco imagery. -

Scientific Programme Monday, 05 March 2018 Youth Pre-Conference

WCTOH 2018 - 17th World Conference on Tobacco or Health, 7 - 9 March, 2018, Cape Town, South Africa Scientific Programme Monday, 05 March 2018 Workshop (WS) 09:00 - 12:30 Beluebell Youth Pre-Conference Workshop Page 1 / 123 WCTOH 2018 - 17th World Conference on Tobacco or Health, 7 - 9 March, 2018, Cape Town, South Africa Scientific Programme Tuesday, 06 March 2018 Workshop (WS) 09:30 - 16:30 Nerina Analysing Global Tobacco Surveillance Data using Epi Info Organized by: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) The Global Tobacco Surveillance System (GTSS) is designed to enhance countries’ capacity to implement and evaluate tobacco control interventions, as well as to monitor key tobacco control indicators. It is comprised of three tobacco surveys: Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS), and Tobacco Questions for Surveys (TQS). GTSS focuses on several topics such as tobacco use, cessation, secondhand smoke, media and advertising, and knowledge and attitudes regarding tobacco use. Epi Info™ is a free software tool designed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for the global community of public health practitioners and researchers. It provides a set of data management, analysis, and visualization tools designed specifically for public health surveillance and evaluation. The workshop will be divided into four parts: (1) overview of GTSS, (2) key features and modules of Epi Info, (3) analyzing GYTS data, and (4) analyzing GATS data. Chair: Candace Kirksey Jones Chair: Simone W Salandy -

Establishing Ecological Agriculture in Faridkot District in Punjab Kheti Virasat Mission

Establishing Ecological Agriculture in Faridkot district in Punjab Submitted by Kheti Virasat Mission A. Organizational Profile: 1. Name of the Organization : Kheti Virasat Mission 2. Address and contact details :Post Box No.- 1, Jaitu, Dist.- Faridkot- 151202(Punjab) Contact Person : Umendra Dutt, Executive Director Phone : 01635-503414 Residence : 9872682161 Fax : 01635-503415 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.khetivirasatmission.org th 3. Registration details : Registered as Trust on 4 March, 2005 (Please enclose relevant : Trust Deed enclosed Photocopies) 4. Details of Exemption : 12 A Copy enclosed (12A and 80G) , 5. Organization Profile Including Objectives And Major Activities: ● To improve the quality of life of farming communities by promoting environmentally safe and sustainable methods that would enhance the quality and quantity of crop yields in Punjab. ● To enhance the participation of farmers, both women and men, in all processes of problem analysis, technology development, evaluation, adoption and extension leading to food security and self reliance among farmers and rural communities. ● To facilitate community access and control over natural resources and to build institutions and coalitions at different levels for strengthening People’s Agriculture Movements, which focus on empowerment of marginalized sections like small and marginal farmers and particularly Women and Dalits. ● To develop a Sustainable Agriculture Resource Network that promotes sharing of knowledge, material and human resources. To serve as a repository for documenting, collecting, storing, collating and disseminating information/success stories from different sources on sustainable agriculture. KVM believes in promoting sustainable agricultural technologies that are based on 1 farmers’ knowledge and skills, their innovation based on local conditions and their use of nature’s products and processes to gain better control over the pre-production and production processes involved in agriculture. -

BAN on ELECTRONIC NICOTINE DELIVERY SYSTEMS in INDIA: a REVIEW Amit Yadav Nisha Yadav

BAN ON ELECTRONIC NICOTINE DELIVERY SYSTEMS IN INDIA: A REVIEW Amit Yadav Nisha Yadav ABSTRACT Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (“ENDS”) were introduced in India in the late 2000s and were getting popular, especially among school going youth and young adults. ENDS were widely promoted and marketed as harm reduction products or safer alternatives to cigarette smoking. Multinational tobacco giants soon gained complete control over the production and marketing of ENDS in an effort to expand the global tobacco industry. The unregulated sale of nicotine, an addictive and psychoactive carcinogen, not only posed a general threat related to the quality and safety standards for ENDS, but also undermined the progress made in tobacco control by re- normalising smoking, appealing to the youth and creating a whole new cadre of dual users (i.e. smokers who use ENDS as the gateway to smoking and vice versa). Moreover, with every passing day scientific research has further pointed to the greater public health risks of ENDS use per se including heart disease, lung diseases, cancer etc. ENDS use has become a youth epidemic in the United States of America with 60 reported deaths from ENDS related lung injury and nearly 2700 others suffering from it. With this background, the Government of India, which had been making piecemeal efforts to curb ENDS in the previous couple of years, finally imposed a comprehensive ban on the production, manufacture, import, export, transport, sale, distribution, storage and advertisement of ENDS in the country. This paper looks at the health and other risks of ENDS use and the legal and public health implications of the recent legislation on its ban in India.