Bronze Age Funerary Cups of Northern Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Early Bryologists of South West Yorkshire

THE EARLY BRYOLOGISTS OF SOUTH WEST YORKSHIRE by Tom Blockeel [Bulletin of the British Bryological Society, 38, 38-48 (July 1981)] This account brings together information which I have encountered during work on the bryology of South West Yorkshire (v.-c. 63). It lays no claim to originality, but is rather a collation of biographical data from disparate sources, and is presented here in the hope that it may be of interest to readers. I have confined myself largely to those botanists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries who made significant contributions to the bryology of v.-c. 63. If there are any omissions or other deficiencies, I should be grateful to hear of them, and of any additional information which readers may have to hand. The Parish of Halifax has been a centre of bryological tradition for over two hundred years. It was there that there appeared, in 1775, the first contribution of substance to South Yorkshire bryology, in the form of an anonymous catalogue of plants published as an appendix to the Rev. J. Watson’s History and Antiquities of the Parish of Halifax. Traditionally, the catalogue was attributed to James Bolton (d. 1799) of Stannary, near Halifax, whose life was researched by Charles Crossland at the beginning of this century (Crump & Crossland, 1904; Crossland, 1908, 1910). Bolton was the author of fine illustrated botanical works, notably Filices Britannicae and the History of Fungusses growing about Halifax, the latter being the first British work exclusively devoted to fungi. However, his work extended beyond the purely botanical. Shortly after the completion of the History of Fungusses, which was dedicated to and sponsored by Henry, the sixth earl of Gainsborough, Bolton wrote to his friend John Ingham: ‘You must know, John, that I have been so long tilted between roses and toadstools, and back again from toadstools to roses, that I am wearied out with both for the present, and wish (by way of recreation only) to turn for awhile to some other page in the great volume. -

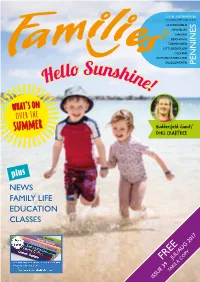

Hello Sunshine!

LOCAL INFORMATION for parents of 0-12 year olds in HUDDERSFIELD DEWSBURY HALIFAX BRIGHOUSE TODMORDEN LITTLEBOROUGH OLDHAM ASHTON-UNDER-LYNE SADDLEWORTH ello Sunshi H ne! what's on over the summer Huddersfield Giants’ EORL CRABTREE plus NEWS FAMILY LIFE EDUCATION CLASSES FREE TAKE A COPY ISSUE 39 JUL/AUG 2017 Project Sport Summer Camps 2017 in Huddersfield and Halifax tra Tim ount • x e sc S E i a e D v e e r g F 1 n 0 i l % b i Book a camp of your choice: S Adventure Day • Bubble Sports Olympics •Archery and Fencing Summer Sports • Cricket • Football 10% OFF WITH CODE FAM2017 Book online 24/7 at projectsport.org.uk StandedgeGot (FMP)_Layout a question? 1 11/05/2017 Call us on 10:20 07860 Page 367 1 031 or 07562 124 175 or email [email protected] Standedge Tunnel & Visitor Centre A great day out come rain or shine. Explore the longest, deepest and highest canal tunnel in Britain on a boat trip, enjoy lunch overlooking the canal in the Watersedge Café and let little ones play in the FREE indoor soft play and outdoor adventure areas. Visit canalrivertrust.org.uk/Standedge for more information or telephone 01484 844298 to book your boat trip. EE FR Y PLA S! AREA @Standedge @Standedge 2 www.familiesonline.co.uk WELCOME School's out for the summer! This is the first Summer where I’ll have both children for the full holiday, which is going to be interesting! There are lots of family attractions right on our doorstep, from theme parks, museums and nature reserves, to holiday camps and clubs where kids can take part in a whole array of activities. -

Yorkshire Wildlife Park, Doncaster

Near by - Abbeydale Industrial Hamlet, Sheffield Aeroventure, Doncaster Brodsworth Hall and Gardens, Doncaster Cannon Hall Museum, Barnsley Conisbrough Castle and Visitors' Centre, Doncaster Cusworth Hall/Museum of South Yorkshire Life, Doncaster Elsecar Heritage Centre, Barnsley Eyam Hall, Eyam,Derbyshire Five Weirs Walk, Sheffield Forge Dam Park, Sheffield Kelham Island Museum, Sheffield Magna Science Adventure Centre, Rotherham Markham Grange Steam Museum, Doncaster Museum of Fire and Police, Sheffield Peveril Castle, Castleton, Derbyshire Sheffield and Tinsley Canal Trail, Sheffield Sheffield Bus Museum, Sheffield Sheffield Manor Lodge, Sheffield Shepherd's Wheel, Sheffield The Trolleybus Museum at Sandtoft, Doncaster Tropical Butterfly House, Wildlife and Falconry Centre, Nr Sheffeild Ultimate Tracks, Doncaster Wentworth Castle Gardens, Barnsley) Wentworth Woodhouse, Rotherham Worsbrough Mill Museum & Country Park, Barnsley Wortley Top Forge, Sheffield Yorkshire Wildlife Park, Doncaster West Yorkshire Abbey House Museum, Leeds Alhambra Theatre, Bradford Armley Mills, Leeds Bankfield Museum, Halifax Bingley Five Rise Locks, Bingley Bolling Hall, Bradford Bradford Industrial Museum, Bradford Bronte Parsonage Museum, Haworth Bronte Waterfall, Haworth Chellow Dean, Bradford Cineworld Cinemas, Bradford Cliffe Castle Museum, Keighley Colne Valley Museum, Huddersfield Colour Museum, Bradford Cookridge Hall Golf and Country Club, Leeds Diggerland, Castleford Emley Moor transmitting station, Huddersfield Eureka! The National Children's Museum, -

The Biology Curator Issue 9-7.Pdf

http://www.natsca.org The Biology Curator Title: LEEDS CITY MUSEUM ‐ its Natural History Collections: Part 3 The Botanical Collections Author(s): Norris, A. Source: Norris, A. (1997). LEEDS CITY MUSEUM ‐ its Natural History Collections: Part 3 The Botanical Collections. The Biology Curator, 9, 5 ‐ 8. URL: http://www.natsca.org/article/476 NatSCA supports open access publication as part of its mission is to promote and support natural science collections. NatSCA uses the Creative Commons Attribution License (CCAL) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/ for all works we publish. Under CCAL authors retain ownership of the copyright for their article, but authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy articles in NatSCA publications, so long as the original authors and source are cited. Collections Management LEEDS CITY MUSEUM - its Natural have entered the museum as part of some other co!Jection, this cannot now be identified specifically, although it History Collections probably came in as part of the William Kirby Collection in Part 3 The Botanical Collections 1917/18. Adrian Norris The main problem resulting fro m the m is-attribution of the Assistant Curator Natural History, Leeds City Museums, collections relate to the entries in British Herbaria (Kent. Calverly St. , LS I 3AA 1957), This publication I ists Leeds Museum as housing the collections of R.B.Jowitt, J.F.Pickard, J.Woods and an ABSTRACT unknown collector. Of these four entries only that for This paper covering the botanical collections held at the R.B.Jowitt appears to be correct. We have now been able to Leeds City Museum, is the third in a series of papers on the identify some 587 sheets as belonging to the collection of museums natural history collections, (Norris, 1993 & 1995). -

DISCOVER Festival DISCOVER DISCOVER

September Halifax 2019 Heritage DISCOVER Festival DISCOVER DISCOVER Most events are free of There will be opportunity charge to attend, a limited to wander around sites few have a small cost or that aren’t usually open to donation requirement. the public, looking at some Halifax Heritage Visitors can expect family of the finest buildings and activities, children’s events, architecture in the North of Festival is back evening talks and lunch England, offering the chance time walks, with historical to interact with the past. lectures, ghostly tales, bigger and Halifax is a town that blends hidden gems, and uncovered the old with the new - come tombs being included in the and discover it for yourself! better than ever! festival. Running alongside the already renowned Heritage Open Days, the Coordinated by Halifax Halifax Heritage Festival offers many unique events Business Improvement taking place, there really is District, with approximately something for all ages. 20 heritage sites hosting Thanks to the success last year, the festival will again events and activities during extend beyond the original the festival with over 60 long weekend, giving you the opportunity to get walks, talks, tours, viewings, involved in heritage exhibitions and live music events across the summer and well into September. events taking place. #discoverhx Events Calendar July August September Thu 18 July – Fri 13 Sept Sat 3 Aug Thu 5 Sept Sat 14 Sept 11am 2pm 7.30pm 10.30am – 4pm Victoria Theatre Queens Road/ Battinson Road The Old Mill, Hall Street Halifax Minster -

Unbound: Visionary Women Collecting Textiles

Published to accompany the exhibition CONTENTS Unbound: Visionary Women Collecting Textiles Two Temple Place, London 25th January – 19th April 2020 Foreword 04 Unbound: Visionary Women Collecting Textiles has been curated Introduction 06 by June Hill and emerging curator Lotte Crawford, with support from modern craft curator and writer Amanda Game and Collectors and Collecting 11 Jennifer Hallam, an arts policy specialist. Stitched, Woven and Stamped: Women’s Collections as Material History 32 Published in 2020 by Two Temple Place 2 Temple Place Further Reading 54 London WC2R 3BD Bankfield Museum 56 Copyright © Two Temple Place Leeds University Library Special Collections 58 A catalogue record for this publication Chertsey Museum 60 is available from the British Library Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts 62 ISBN 978-0-9570628-9-4 Compton Verney Art Gallery & Park 64 Designed and produced by: NA Creative The Whitworth, University of Manchester 66 www.na-creative.co.uk Cartwright Hall Art Gallery 68 Object List 70 Unbound: Visionary Women Collecting Textiles is produced by The Bulldog Trust in partnership with: Acknowledgements 81 Bankfield Museum; Cartwright Hall Art Gallery, Bradford Museums and Galleries; Chertsey Museum; Compton Verney Art Gallery & Park; Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts; Leeds University Library Special Collections and Galleries and the Whitworth, University of Manchester. 02 03 FOREWORD An exhibition is nothing without its spectacular objects and for those we would like to thank our partner organisations: Bankfield Museum; Charles M. R. Hoare, Chairman of Trustees, -Cartwright Hall Art Gallery; Chertsey Museum; Compton Verney The Bulldog Trust Art Gallery & Park; Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts; Leeds University Library Special Collections; and the Whitworth, University of Manchester, for loaning so generously from their collections and for their collaboration. -

Angharad Thomas CURRICULUM VITAE

Angharad Thomas CURRICULUM VITAE Qualifications 2011 University of Salford PhD. The role of design in sustainable development: a qualitative exploration in the context of Welsh textile production 1997 Bradford and Ilkley College H.N.C. Handloom weaving 1986 Trent Polytechnic M.A. Knitwear and Knitted Fabric Design 1973 City of Leeds and Carnegie Diploma in Education, Geography and Art College 1971 Bedford College, University of B.Sc. (Hons) Geography/Geology London Membership of Professional Bodies Design Research Society. Textile Society. Knitting & Crochet Guild. Heritage Crafts Association. Universities and Colleges Union. Crafts Council Directory listed maker. Creative Kirklees listed maker. Employment history: summary 2012 – present Independent scholar. Craftsperson, designer and maker Textile archivist at the Knitting and Crochet Guild collection, Holmfirth, Yorkshire (voluntary part time post) Selected professional engagements and awards 2020 Knitting History Forum. Holy Hands: a study of liturgical gloves, presented paper via Zoom 2020 Textile Society of America Symposium, Hidden Stories/Human lives. Hidden stories in the collection of the Knitting & Crochet Guild of the UK. Selected presentation via Zoom. 2020 Janet Arnold research grant awarded for ‘Holy Hands: a study of liturgical gloves’. Society of Antiquaries, London 2019 Hand in Glove, Invited speaker, East Yorkshire Embroidery Society. 2019 For the love of gloves. Keynote speaker: Knitting & Crochet Guild Convention, University of Warwick 2017 Invited presenter: The Nature -

West Yorkshire Textile Heritage Project

West Yorkshire Textile Heritage Project 1. Introduction The West Yorkshire Textile Heritage Project, is a partnership project between Bradford, Calderdale, Kirklees and Wakefield Museum and Gallery services. The partnership has received a grant from the Esmee Fairbairn foundation to undertake a project which draws together the significant textile heritage collections held by these organisations. This will be achieved through a programme of research and documentation, to enhance what services know about their own and other regional collections. The collections will be made accessible via a website, acting as a single portal for information across the region. A textile heritage trail, linking museum collections with the built industrial heritage of the region, will be created with support from Welcome to Yorkshire. This support will take the form of hosting the trail on their website and printing the final publication. It is envisaged that this trail will also include, and develop links with, local businesses occupying mill premises. The project is an innovative pilot for future working across the region and contributes to the sustainable future development of the region’s museums and collections. 2. Purpose of this brief To seek a contractor to deliver the key outcomes of the project, within the defined timescale and budget. For the successful contractor to work with supporting organisations, such as Welcome to Yorkshire, other custodians of West Yorkshire textile collections/information and relevant businesses, to produce the tourist trail and website. 3. Background West Yorkshire was a major centre of textile production from the 18th century and the industry is still important today. The industry has left its physical marks across the region in everything from pack horse bridges and weavers cottages to mill owner’s mansions and large scale factories. -

Contemporary Art Society Report 1940-41

Contemporary Art Society - REPORT 1940-41 THE CONTEMPORARY ART SOCIETY FOR THE ACQUISITION OF WORKS OF MODERN ART FOR LOAN OR GIFT TO PUBLIC GALLERIES President LORD HOWARD DE WALDEN Chairman SIR EDWARD MARSH K.C.v.o., C.B., C.M.G. Treasurer THE HON. JASPER RIDLEY 440 Strand,W.C.2 Joint Hon. Secretaries LORD IVOR SPENCER-CHURCHILL g Dilke Street, S.W.3 ST. JOHN HUTCHINSON, K.C. Merton Hall, Cambridge Committee SIR EDWARD MARSH, K.c.v.o., C.B., C.M.G.(Chairman; The Earl of Crawford and Balcarres Lord Keynes, c .B. Sir Muirhead Bone J. B. Manson Miss Thelma Cazalet, M.P. Ernest Marsh Sir Kenneth Clark, K.C.B. The Hon. Jasper Ridley Samuel Courtauld J . K. M. Rothenstein Sir A. M. Daniel, K.B.E . Sir Michael Sadler, K.c.s.1., c.B. Campbell Dodgson, c.B.E. The Earl of Sandwich A. M. Hind, O.B.E. Lord Ivor Spencer-Churchill St. John Hutchinson, K.C. C. L. Stocks, c.B. Assistant Secretary: R. IRONSIDE Printed in England at The Curwen Press Speech by the Chairman at the Eleventh Ordinary General Meeting of the C.A.S. held at the Tate Gallery on May 20, 1942 "Ladies and Gentlemen, We are keeping our heads above water, we are keeping the flag flying; and at the same time we are cutting our coat according to our cloth-acting, in fact, as best we can on all the maxims appropriate to times of difficulty-so I hope to be able to show that in the year which has passed since I last addressed you we have been conducting our affairs with a combination of courage and prudence. -

YORKSHIRE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY List of Members, 1941

Downloaded from http://pygs.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on October 2, 2021 YORKSHIRE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY List of Members, 1941 HONORARY MEMBERS. FEARNSIDES, W. G., M.A., F.R.S., F.G.S., 11, Ranmoor Crescent. Sheffield 10. GARWOOD, E. J., M.A., Sc.D., D.Sc., F.R.S., F.G.S., 90, Adelaide Road, London, N.W.3. SHEPPARD, T., M.SC, F.G.S., F.Z.S., The Museums, Hull. WOODWARD, SIR A. SMITH, Kt., LL.D., D.Sc, Ph.D., F.R.S., F.C.S., F.L.S., Hill Place, Haywards Heath, Sussex. ORDINARY MEMBERS. ABBOTT, A„ 78, Ash Road, Leeds 6. AIERS, A. J., Sycamore Mount, Kinders, Greenfield, nr. Oldham. AIREY, MRS. C. N., 70, Stainburn Crescent, Leeds 7. ANDERSON, F. W., M.Sc, Geol. Survey Office, 19, George Terrace, Edinburgh. ASHWORTH, J. H., 151, St. Andrews Road South, St. Annes-on-Sea. ASTON, R. L., 31, Cliff Road, Leeds 6. ATKINSON, F. S„ M.Eng., M.I.M.E., Mining Dept., The University, Leeds 2. BAIRSTOW, L., M.A., F.G.S., Department of Geology, British Museum (Natural History), London, S.W.7. BARKER, W. R., F.G.S., 15, Fitzwilliam Avenue, Wath-on-Dearne. BAYNES-SMITH, W., 15, Montagu Place, Leeds 8. BEAUMONT, A. G., M.Inst.C.E., 23, Castle Road, Sandal, Wakefield. BEEVERS, C., Broom Grove, Bessacarr, Doncaster. BEILBY, R. B., M.C., A.M.I.M.E., Hoddon Manor. Nr. Peter• borough. BELBIN, H. L., 69, Crawshaw Grove. Beauchiel Sheffield 8. BEVERIDGE, J. P., A.M.I.C.E., Waterworks Dept., Huddersfield. -

Museums Collecting Archaeology

Museums Collecting Archaeology (England) REPORT YEAR 1: November 2016 Prepared by: Gail Boyle Nick Booth Anooshka Rawden Museums Collecting Archaeology (England) Year 1 Report: November 2016 “It is important that the position of all museums, especially small museums, is recognised: lack of space, expertise and communications with archaeology community. This is a crisis!!” Charitable Trust museum, South West Still collecting archaeological archives, and charging a deposition fee “Our collecting area was reduced…to just the Borough boundary. We have been hoping to deaccession material from the wider area, but no-one has space to take it.” Local Authority museum, South East Still collecting archaeological archives, and not charging a deposition fee “We are heavily reliant on volunteers who work specifically with the archaeology collection. They have a background in amateur archaeology and are very knowledgeable in relation to our specific material.” Independent museum, South East We have stopped collecting archaeological archives, but intend to do so again “Museum team decreased from 3 to 1 person. Other archaeologist on staff was made redundant. None of the Archaeological work I do would be possible without the support and assistance of [the local] Archaeological Society. If they did not exist or were not willing to help, the archive would be totally moribund.” Local Authority museum, London & East Still collecting archaeological archives, and not charging a deposition fee i Museums Collecting Archaeology (England) REPORT YEAR 1: November -

Contemporary Art Society Annual Report 1959-60

Contemporary Art Society Annual Report Presentations to Art Galleries not recorded in 1959 Report Chairman's Ballarat, Australia: Graham Sutherland. Two Lyrebirds (gouache) Report Bournemouth: Frederick Gore. Olive Trees, Alpilles (oil) Exhibitions to which the Society has loaned 'Seventy Years of British Painting' Britain China Friendship Association Exhibition in China 'Contemporary British Landscape' Arts Council Touring Exhibition 'Art Alive' Northampton Museum and Art Gallery 'Eric Gregory Memorial Exhibition' Temple Newsam House, Leeds National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh Nottingham University Art Gallery Slough Picture Collection Society Loans of Pictures to Hospitals, Colleges, and Educational Bodies Department of Anatomy, University College, London St Giles Hospital The Electricity Council Mond Nickel Company Architectural Association Sir Colin Anderson, who has been our Chairman our gifts to member galleries during the period Leonor Fini Exhibition on the 2nd November, and on since January 1957, resigned in July 1960 on 1910-1959. Some 36 member galleries, including the the 5th December, members had the unique becoming Chairman ofthe Tate Trustees. Sir Colin Tate Gallery (to whom we are most grateful for opportunity of hearing Mr Bryan Robertson's has been a most wonderful Chairman. He has devoted housing our exhibition), the Victoria and Albert excellent lecture on Henry Moore at the Whitechapel his great knowledge, taste and enthusiasm to the Museum and the British Museum lent some two Art Gallery. The lecture, for which we are most interests of the Society and we have greatly hundred works, which included oils, water-colours, grateful to Mr Robertson and the Trustees ofthe benefited. We shall miss him very much, and I know drawings and sculpture.